I am on Avianca flight 69, Miami to Cartagena, Colombia. Small talk with the lady at my right (she’s Colombian, married to a New Jersey Cuban, going back to see relatives) helps pass the time. When I mention that I’m researching Gabriel García Márquez, she remarks, “Oh, his wife comes from Aijona, my hometown,” then asks if I’ve read García Márquez’s latest book of interviews. As we come in for a landing, the guayabera-clad businessman in front looks over to tell me he’s from Ciénaga, a city located near García Márquez’s birthplace and mentioned here and there in his novels. “By the way, you won’t be needing your corduroy coat in Cartagena,” he adds. “It gets pretty hot.”

Culturally and geographically, Cartagena feels more like Havana or San Juan than Andean America. One is ever aware of the sea. During the Empire, the town was a chief embarkation point for gold treasures being shipped off to Spain. Today, the main thoroughfare, the Malecon, is bordered by the Caribbean, and the tourist area sits on a long narrow strip jutting out into the blue. At night one sees people of all ages standing about, playing salsa music on their radios or keeping rhythm to the Latin bands that liven up the cafés. As in much of the rest of the Caribbean, final s’s tend to disappear from the spoken language. Folks also say chévere! (“great!”), as Puerto Ricans do.

García Márquez began his professional life in Cartagena. He started out in 1948 as a reluctant law student, then took his first job as a reporter for El Universal, a local daily still housed in a, white, neatly balustraded, somewhat decayed building in the charming old center of town. Though he lived here for only two years, Cartagena stayed with him, and he used it decades later as the model for the city in Autumn of the Patriarch. The Patriarch often stands on his balcony overlooking the sea, where he can take in “the smell of rotten shellfish,” “the fortress of the harbor” (a typical feature of Caribbean ports, here an impressive hulk named San Felipe), the “high house that looked like an ocean liner aground on top of the roofs” (a precise description of Cartagena’s Monastery of La Popa, so called because it resembles the stern-lapopa-of a big ship), and the “Negro shacks on the promontories.” As in García Márquez’s thick novel, the street life in this beach town is both casual and intense.

The next day I move on to Barranquilla, traveling in a 1956 Dodge bus that is well-maintained, decorated with bright stripes, and equipped inside with radio speakers. “¡Musica, maestro!” shouts a passenger as we depart. The driver flicks the button and a sportscaster’s frenzied voice fills the aisles.

While the countryside is lush green, the dusty poverty of the hamlets we chug through makes Faulkner’s Mississippi seem prosperous by comparison. An occasional burro stands immobile by the wooden huts. I ask two young women behind me for the name of the crop being grown in the fields, and this leads to the usual questions about my provenance and travel plans. I mention García Márquez and one of the two, a business student, chimes in enthusiastically, “Oh, my father went to high school with him. In fact, Papa recently showed me a little sketch García Márquez once did of him for the school paper.” Both she and her companion, who studies social work, have read through all of García Márquez’s work except Autumn of the Patriarch. “I don’t understand it,” the future social worker chuckles, “but a classmate of mine studies literature, and she’s been explaining the book to me. So maybe I’ll read it someday.”

Barranquilla, the commercial capital of the Colombian north, is not an attractive city. Its Hispanic old core, its American-style new suburbs, and its “enterprise zones” on the Magdalena River show the familiar sprawl and bustle of industrial monsters like Mexico City. It was here, however, that García Márquez first met, in 1950, a sympathetic literary crowd that nourished his gifts. Indeed, “the Barranquilla Group” is now a set phrase, much like “the Black Mountain Poets” or “the Partisan Review crowd.” Here, too, García Márquez launched his real reputation as a journalist, with a daily human-interest column entitled “The Giraffe” (so named because of its long, narrow-column format) for El Weraldo. In search of back issues I head for the newspaper’s shiny new offices and talk to writer and editor Germán Vargas, one of García Mitrquez’s original Barranquilla buddies. Mr. Vargas is also a character in One Hundred Years of Solitude, Germán by name (what else?), one of four young boozers who befriend the scholarly and virginal Aureliano Babilonia, last of the Buendía clan.

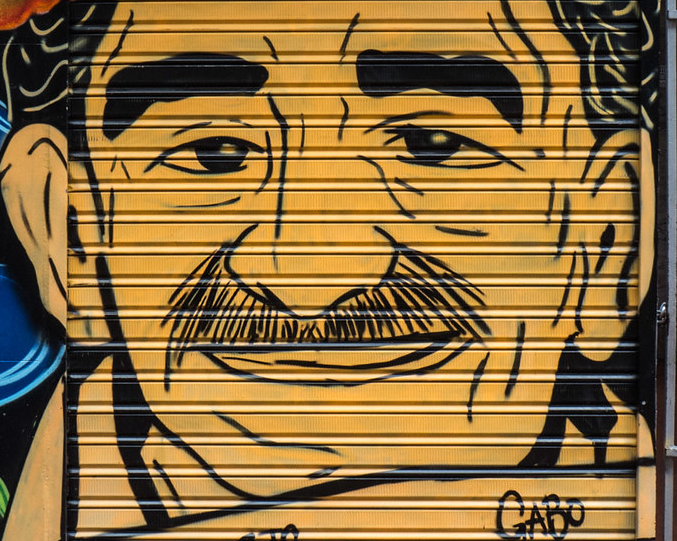

In Cartagena I had seen a drugstore and an apartment building named “Macondo,” after the village in One Hundred Years of Solitude. In Barranquilla, I notice a “Macondo” grocery. García Márquez is, in countless such ways, a presence throughout Colombia. In the Sunday papers I come across an interview with him, a “giraffe” from 1950 (they’re currently being rerun by El Heraldo), along swipe at his leftism by a conservative named Alicia del Carpio, several passing references to him or his books, and the weekly syndicated column he writes today. As often as not, the press and ordinary folks alike will invoke García Márquez by his nickname “Gabo” or even the diminutive “Gabito.” It’s as though everyone in New York were to refer to Doctorow as “Ed” or Malarnud as “Bernie.”

García Márquez’s saga of Macondo has helped catapult yet another author to fame—posthumously. Aureliano Babilonia has a mentor, a “wise Catalonian” who loans him books. This was García Márquez’s heartfelt homage to Ramón Vinyes, a real-life Catalonian and exiled bookseller who in 1950 introduced a budding Gabito to all sorts of modern European and U.S. literature. On his death in 1952, Vinyes left heaps of drama and fiction manuscripts of his own—all in Catalonian. Thanks to García Márquez’s loving portrait, Vinyes has since become a popular legend. Allusions to the original for the “wise Catalonian” appear from time to time in the press, and his works are now being published in Spain.

Though García Márquez’s experience proved that Barranquilla can be a nice place to live, it’s no city for a visit. There is little to look at, and the streets turn dangerous at night, with street urchins straight out of movies like Los Olvidados or Pixote. Next day I’m on on a bus to Anracataca, Gabo’s first hometown and model for Macondo. The two salesmen in front—one Indian-looking, the other Afro-Colombian—are very helpful in explaining to me just when I should get off. We talk a bit about García Márquez, and they ask, Oh, is that why you’re headed for Aracataca? The bus radio plays salsa music; a passenger somewhere is singing along. A nurse and I converse about her job, the local food and vocabulary, and of course García Márquez. She and her parents both own his complete works.

During the first half of the two-hour trip we have the Caribbean on our left and drive by small coastal settlements of the sort García Márquez depicts in stories like “The Sea of Lost Time.” Soon we are skirting the marshes and mountains that the Buendias traversed in their futile quest for a promised land. On one lengthy isthmus the ocean is to our left, a vast swamp to our right, and I recall José Aracdio Buendía’s exclamation, “God damn! Macondo is surrounded by water on all sides!” When we make a stop in the town of Ciénaga, the bronze-skinned salesman points out for me the solemn memorial to the massacred United Fruit workers: there, in the main plaza, is a huge brown statue, at least fifty feet high, of a monumental Negro brandishing a machete in his right hand.

The peoples of Caribbean Colombia are known as costeños (“coastals”). García Márquez is of this stock, and he has succeeded admirably in giving the costeños a literary profile, a place in world culture, much as Faulkner did for the Deep South. He’s their writer. Foreigners tend to think of Colombia as Andean and Indian, but that is an incomplete picture. The coastals see themselves as ethnically, culturally, and temperamentally distinct from the Bogota people, whom they refer to as cachacos (roughly, “highlanders”). Ostensibly descriptive or just funny, the term can carry the same hostile force of any Alabaman saying “those Yankees.” And indeed the coastals look upon the highlanders much the same way that Southerners or Californians see Yankees—cold, arrogant, uptight.

At last we arrive in Aracataca. Population 17,000. The town looks much smaller, but a short walk reveals that it spreads out, There are no paved roads, and the thick air is indeed dusty, and among those dirt roads is the Street of Turks—as in Macondo. Many of the dwellings are wooden shacks, sitting side-by-side with concrete homes. A peculiar tropical stillness prevails—most cars are silently parked, and no coastal breezes bring relief. With the noontime heat, many townspeople use umbrellas as parasols or linger in cafés. The open-air movie house depicted in Gabo’s In Evil Hour is now an insurance business. Piglets romp and little boys play soccer by the tracks leading to the forlorn railway station marked ARACATACA, the only sign I will see here with that name. Two railway employees are playing dominoes, someone is snoozing on a bench. This is the place.

The telegraph office that employed Gabito’s father still operates in the town square; the yellowish church, where some of García Márquez’s more memorable scenes take place, is also there. Between them is the road to the cemetery, walked by the fearless mother in Gabo’s story “The Tuesday Siesta.” It’s not siesta time now—women are running errands, uniformed kids are coming home from school. The gate to the cemetery was locked in that story, but today it isn’t. Among the first gravestones I see are for Mercedes and Ester Ternera—the family name of the lusty seductress-procuress in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

I pay a visit to City Hall. The current mayor—who knew Gabito as a five-year-old—is away at a conference, but an ex-mayor happens to be there. Tall, broad-shouldered, he wears sunglasses and rides motorcycles, and he gives me a few instances of Aracataca’s sudden world renown. French TV crews have been here twice to take footage (which the Aracatacans never got to see). “That was in ’72 and ’77. Also, once in a while tour buses filled with Europeans or Americans show up. They pile out, take pictures, and then leave, since they rarely know Spanish.” I go for a walk with the twenty-two-year-old General Secretary and ask if Aracataca has acknowledged her native son. “The high school has a literary room named after him. But,” he adds, “there’s some resentment against Gabo. Since he became famous he’s been back just once, and that was for a music festival. You’d think the government would at least acknowledge us with a couple paved roads.”

The Secretary introduces me to a senior citizen, a crusty sort who once worked as a timekeeper for United Fruit. “Those were good times,” he reminisces, “lots of money back then. Several of my brothers also worked for the Fruit Company. You know those photos of people, dancing with burning peso bills in their hands? Well, that’s how it was.” I ask how he felt about the strikers. He gets impatient. “Those people only made a mess of everything. And let me tell you—all that talk about workers being massacred just isn’t true. It never happened. The most I ever heard of was two guys shot. Look, if there really were all those dead, then where’d they dump the bodies?” It’s not often that one gets to live, almost verbatim, a key scene from Gabo’s book.

The Secretary leads me eight houses away from the square to García Márquez’s first dwelling place. A Señora Iriarte lives there now in a modem, pate green house, but she preserves, virtually as a shrine, that portion of the García home where Gabito had been born. Standing in the afternoon glare, peering through the front window of the concrete facade, I can dimly make out some white wooden walls in back. That’s where it all began.

A week later, in Mexico City, I am watching Gabriel García Márquez attach a compass to the dashboard of his BMW. “The compass of Melquiades,” he joshes. His wife Mercedes, who is as beautiful and warmly engaging as literary rumors say (and who is the mysterious pharmacist, named Mercedes, encountered by Aureliano Babilonia during the last days of Macondo) explains that her husband tends to get hopelessly lost in the vast Mexican megalopolis, despite twenty years’ residence there. Hence the compass. Curly-haired and about 5’6″, García Márquez emerges from the car wearing blue one-piece overalls with a front zipper-his morning writing gear. At this point their son Gonzalo, a very Mexican twenty-year-old, shows up with a shy, taciturn girl friend. The in family banter grows lively, and García Márquez’s soft-spoken Spanish and dropped s’s immediately recall the Caribbean accent of the Colombian coast.

Even before he won the Nobel Prize, the Hispanic press had besieged García Márquez with an attention normally reserved for movie stars and football heroes. My meeting with him, consequently, has meant negotiating an obstacle or two. I started out with my novelist friend Jorge A_____, who talked with the wife of a painter friend of his, who then obtained for me an introduction to Luis V____, a bookseller who is an old buddy of García Márquez’s from the 1950s. I spent an enjoyable two hours with Luis V apparently he approved, as he allowed me García Márquez’s telephone number, which I tried that evening. A female voice answered; I stated my business and she passed me on to Gonzalo, who listened politely to my speech and said Papá isn’t in but could I call back Thursday at one? Next day I got several busy signals before reaching the female voice, who seemed to remember me and gave the phone to Senora García, who in turn listened to my speech, said her husband was out with friends, and suggested I call back Saturday morning at eight. Seventeen nervous hours later I again spoke to the female voice, with Gonzalo, and again with Dona Mercedes, who said García Márquez was busy writing but could see me at one o’clock, for ninety minutes, since he had a 2:30 lunch date. “Will that be enough time for you, sir?” Mrs. García asks.

Global fame notwithstanding, García Márquez remains a gentle, unassuming, indeed an admirably balanced and normal sort of man. As he and Gonzalo lead me across the little garden to his office—a separate structure equipped with special climatization, various encyclopedias and other useful books, paintings by Latin American artists, and a Rubik’s cube—I find it easy to imagine García Márquez in a downtown café, sipping beer with the jukebox repairman or trading stories with the short-order cook.

GB-V: How many languages has One Hundred Years of Solitude been translated into?

GGM: Thirty-seven at my wife’s latest count.

How did the Japanese version fare? Did readers understand it?

It caught on fast. Not only did they understand the book, they thought of me as Japanese! But then I’ve always been a devoted follower of Japanese literature.

Outside of Spanish, which language has it sold best in?

It’s hard to track down. The first Russian edition sold a million copies, in their foreign literature magazine. Apparently they’re preparing translations into other Soviet languages too. The Italian version has done well, I believe. There are also pirated editions in Greek and Farsi—oh, and in Arabic. Arab readers seem to like the book. I hear those pirated translations aren’t very good, though.

There’s a very famous strike scene in One Hundred Years. Was it much trouble for you to get it right?

That sequence sticks closely to the facts of the United Fruit strike of 1928, which dates from my childhood; was born that year. The only exaggeration is in the number of dead, though it does fit the proportions of the novel. So instead of hundreds dead, I upped it to thousands. But it’s strange, a Colombian journalist the other day alluded in passing to “the thousands who died in the 1928 strike.” As my Patriarch says: it doesn’t matter if something isn’t true, because eventually it will be!

You maintain a certain lightness of tone in that scene.

The Yankees are depicted the way the local people saw them, hence the caricature with Virginia hams and blue pills. You see, some of my relatives back then had defended the Americans and blamed the strikers for “sabotaging prosperity” and all that, so this was my reply. Of course, my own view of Americans is a lot more complex, and I attempted to convey those events without any hate.

Your One Hundred Years of Solitude is required reading in many history and political science courses in the U.S. There’s a sense that it’s the best general introduction to Latin America. How have you felt about that?

I wasn’t aware of that fact in particular, but I’ve had some interesting experiences along those lines. René Dumont, the French economist, recently published a lengthy academic study of Latin America. Well, right there in his bibliography, listed amid all the scholarly monographs and statistical analyses, was One Hundred Years of Solitude! On another occasion a sociologist from Austin, Texas came to see me because he’d grown dissatisfied with his methods, found them arid, insufficient. So he asked me what my own method was. I told him I didn’t have a method. All I do is read a lot, think a lot, and rewrite constantly. It’s not a scientific thing.

Some left- wing critics take you to task for not furnishing a more positive vision of Latin America. How do you answer them?

Yes, that happened to me in Cuba a while ago, where some critics gave One Hundred Years of Solitude high praise and then found fault with it for not offering a solution. I told them it’s not the job of novels to furnish solutions.

So what was your aim in Autumn of the Patriarch?

I’ve always been interested in the figure of the Caribbean dictator, who’s probably our one and only mythic personage. Where other countries have their saints, martyrs, or conquistadors, we have our dictators. I feel that the dictator is a product of ourselves, of our Caribbean culture, and in that book I tried to achieve a serene vision. I don’t condemn him. Of course, I portray an earlier sort of dictator, unlike the ones today, who’re propped up by a technological apparatus. They’re technocrats, whereas those older dictators were often anti-imperialists, like Venezuela’s Juan Vicente Gómez, who declared war on England and Germany.

What about the technique in that book?

Since I wanted to create a synthesis, a composite character, I had to resort to a new narrative method. A lot of people thought the book hard going, but more and more readers now find it perfectly natural. Children today can read through much of Autumn of the Patriarch. I’m not equating myself with Picasso, but it’s a bit like his Cubist and other techniques, which seemed forbidding at first, yet soon became just another way of putting things together.

Did you read Emperor Jones?

I had Emperor Jones in mind, together with lots of other stuff. For ten years I devoured material dealing with Latin American dictators, and also studies of power, such as Suetonius. And afterwards I tried to forget it all! I first read everything by O’Neill while I was in high school, though. It’s interesting, my basic literary background consists of Spanish Golden Age poetry and twentieth-century U.S. fiction. But then, the American part is obvious. (He laughs.)

You’ve said on occasions that Bela Bartók is a prime influence on your work. Is it the way he combined folk with classical art?

That, and his sense of structure. Bartók is one of my favorite composers; I’ve learned a great deal from him. My novels are filled with symmetries of the kind Bartók has in his String Quartets. (People think I’m a spontaneous writer, but I plan very carefully.) Although I’ve no technical knowledge of music, I can appreciate Bart6k’s use of form, his architecture. Bartók also had a profound feeling for his people, and for their music. His iconography is amazing, too. There’s a beautiful photograph of Bartók out in the field, turning the crank on a gramophone for a peasant woman to sing into it. He worked hard, you can see.

You’re a writer with a very intimate knowledge of street life and plebeian ways. What do you owe it to?

(He reflects for a moment.) It’s in my origins; it’s a vocation, too. It’s the life I know best and I’ve deliberately cultivated it.

Those smugglers in Innocent Erendífrá, for instance-how did you get informed about them?

Oh, I grew up with smugglers! They were relatives of mine, uncles and cousins operating on the Guajira Peninsula, where I set Erendífrá. Much of that contraband is gone today. The stuff they smuggled now gets stocked in the duty-free shops; the rest has become internationalized and Mafia-controlled.

With fame, is it hard, keeping in touch with your popular roots?

It’s tough, but not as much as you’d think. I can go to a local café, and at worst one person will request an autograph. What’s nice is that they treat me like one of their own, especially in hotels up in the States, where they’ll feel good just meeting a fellow Latin American and sharing their gripes about the U.S. But I never lose slight of the fact that I owe all these experiences to the many readers of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Where it does get difficult is at public events—literary cocktails, government functions, the like. The minute I walk through the door, I find myself surrounded by people who want to talk with me. My biggest struggle is leading my private life, so I’m always with my old friends, who shield me from the crowds.

How has being a journalist influenced your writing?

Journalism keeps you in contact with reality. I write a weekly syndicated column for ten newspapers and a magazine. And it helps, it’s like a pitcher keeping his arm warmed up. You know, literary people have a tendency to get off on all sorts of unreality. Besides, if you stick to writing only books, you’re always starting from zero again.

On weekends I head out for my place in Cuernavaca and go through all kinds of magazines, clipping things from Nouvel Observateur, Le Point, and I used to read Time but since shifted to Newsweek. [He laughs.]

Can you, a Latin American leftist, really stand to read Time?

Well, I admire the techniques of U.S. journalism, the carefulness with facts, for example. Of course, it’s all manipulated to fit a point of view, but that’s another problem. There are also excellent non-Marxist leftists in the States, like The Nation people. I always pay a visit to my friend Victor Navasky when I’m in New York.

You’re on the U.S. Immigration blacklist. What’s the story?

It’s a strange situation. In the early 1960s I was New York correspondent for the Cuban press agency, Prensa Latina. Then, in 1961, I resigned over political disagreements, and left for Mexico. I was denied entry into the U.S. for ten years after that. But in 1971, Columbia University gave me an honorary doctorate, and a one-shot visa came through. Later, the Immigration people decided that if I do something that benefits the U.S., such as deliver a lecture, they’d let me in, so Frank MacShane at Columbia was finding me lecture invitations. Eventually a secret pact took shape between the authorities and myself. They don’t want the media making an issue over this thing, so if I show them an official document asking me to talk, they’ll give me a visa.

At any rate, I never really understood why they’ve got me in their black book-or yellow book, to be precise. My political views are clear. They may resemble the views of many a Communist Party man-but I’ve never belonged to a party. As far as I know, you can’t deny people entry just on the basis of their ideas. [Gonzalo steps in, says quietly “They’re here,” and sticks around to pick up the beer bottles and glasses. García Márquez and I round off a couple of other topics, and he asks if I have any more questions. I quickly search in my notebook for an appropriate finale.]

And which of your books is your favorite?

It’s always the latest, so right now it’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold [scheduled for U.S. publication this April]. Of course, there are always differences with readers, and every book is a process. I’m particularly fond of No One Writes to the Colonel, but then that book led me to One Hundred Years of Solitude.

García Márquez remains his amiable self, and as we stroll through the garden the three of us make small talk about Mexican taxis, life in Paris, American leftists, foreign languages, and also Harvard College, where his other son Rodrigo, is a senior majoring in history. At the garden gate we shake hands, Gonzalo cordially offers a ride to the nearest taxi stand, and my conversation with the great novelist ends the way it began—with the youngest member of his family.