African Americans have sought liberation from racial oppression by virtually every form of protest, with nonviolent resistance the most lauded in national memory. Appeals to law, such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and public opinion, such as the 1963 March on Washington, have left impressive legacies. Directed by racial integrationists such as Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King, and the leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), this strand of protest challenged and changed but did not seek to alienate or overthrow the white establishment, at least those sectors of it amenable to liberal racial reform.

A competing strand pledged to use “any means necessary” to gain and exercise self-determination. The most influential champions of this approach sought a radically reconfigured society, not one in which blacks are merely assimilated into existing hierarchies. Compared to the likes of King and Marshall, the figures and organizations associated with the more disruptive tradition—Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Huey Newton, the post-1965 Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party—have not fared nearly so well in public esteem. In the popular memory of the 1960s and 1970s, the ascendant view holds that black power protest contributed little to improving black lives and, through its violent rhetoric and action, undercut the efforts of the integrationists. Revisionists have come forward to challenge this view. The late Manning Marable’s Malcolm X, Peniel Joseph’s Stokely: A Life, and Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr.’s Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party all seek to elevate the reputations of black power radicals. But their efforts are subverted by sloppy argumentation and insistent adulation. In each of these books, analysis is overshadowed by hagiography.

Malcolm X

Named Malcolm Little by his parents, the man later dubbed Malcolm X was born in Omaha, Nebraska, May 19, 1925. He suffered a traumatic childhood. At the age of two, he moved with his parents to a house on the outskirts of Lansing, Michigan. Perhaps unbeknownst to the Littles, the house was encumbered by a racially restrictive covenant—a contract in which the previous owner of the property had promised not to sell it to blacks. White neighbors sought and obtained a court order evicting the Littles. Before the order could be carried out, other whites adopted a more aggressive means of driving the Littles away: they burned the house down.

When Malcolm was only six, his father was run over by a streetcar. Maybe the death was an accident. But Malcolm perceived the matter differently as an adult, and not without justification. Earl Little may well have been murdered by white supremacists who were angered by his independence and racial pride; he was a stalwart and vocal supporter of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. After her husband’s death, Louise Little broke down mentally and was institutionalized for the remainder of her life. Consigned to foster care or the loose supervision of older siblings, Malcolm was eventually expelled from school. He supported himself with menial employment in New York City and Boston, took illicit drugs, and eventually turned to serious crime. At twenty-one he was sentenced to prison in Massachusetts for burglary and larceny.

In the course of his six-year incarceration, Malcolm was introduced to the Nation of Islam (NOI). His older siblings extolled the virtues of the sect. Its autocratic leader, “The Messenger” Elijah Muhammad, preached a unique theology, which synthesized some of the nomenclature and symbolism of Islam with a cosmology that refracted the peculiar experience of blacks in America. While American culture, secular and religious, has typically privileged whiteness and derogated blackness, the NOI reversed this paradigm.

According to Elijah Muhammad, blacks were the Earth’s “original” people. An evil scientist, Dr. Yakub, created whites, who succeeded for centuries in enslaving and otherwise exploiting and oppressing blacks. Whites, whom Elijah Muhammad called “devils” and “archdeceivers,” succeeded in divesting blacks of virtually everything valuable, including their very names. The surnames of most blacks, Elijah Muhammad asserted, were shameful “slave names” that obscured their true identities. Elijah Muhammad, named Elijah Poole at birth, assured his followers it was God’s will for blacks to regain their initial and rightful ascendancy. He insisted, though, that in preparation for that glorious and fast-approaching turnabout, blacks should separate themselves from whites, develop economic self-sufficiency, and cleanse themselves physically and morally by forsaking liquor, drugs, swine, and fornication.

Malcolm X was a poor leader, subject to all manner of bad ideas, who constantly misjudged people.

Upon leaving prison in 1952, Malcolm X showed himself to be a driven, resourceful, and charismatic disciple. He drew converts, resuscitated failing temples and established new ones, and delivered countless speeches differentiating what he depicted as the dignified separatism of Black Muslims from the craven integrationism of Uncle Toms and other “so-called Negroes” who begged the white man for acceptance. While civil rights activists encouraged blacks to vote and otherwise participate in every sphere of American life, Malcolm X, following the teachings of Elijah Muhammad, eschewed voting and protest, reasoning that the United States was unchangeable and irredeemable. While civil rights activists repudiated the notion that the United States was a white man’s country, Malcolm X insisted it was and always would be.

With his provocative speeches, military bearing, forbidding countenance, and biting wit, Malcolm X captured the attention of curious whites, such as the television journalist Mike Wallace, who aired a show, “The Hate That Hate Produced,” which elevated Black Muslims’ public profile. Ironically, while Malcolm X at this time constantly expressed contempt for whites, deriding them as “blue-eyed devils,” it was the fascination of white journalists and academics that made him into a minor celebrity on television, radio, and college campuses.

That very fascination helped to undo Malcolm X. It brought to him prestige and prominence that exceeded the notice accorded others in the Black Muslim leadership. Envious of his protégé, Elijah Muhammad first muzzled and then hounded Malcolm X, prompting him to leave the NOI in March 1964.

In the last year of his life, Malcolm X conducted himself with the whirlwind energy of a man who intuited that he had little time left. He embraced orthodox Islam, completed the hajj (the pilgrimage to Mecca that Muslims are obligated to undertake if possible at least once in their lifetime), renamed himself El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, traveled widely in Africa and the Middle East, renounced the NOI’s anti-white theology, threw himself into political activism that had previously been off limits, founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity, and collaborated with Alex Haley in writing The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965). Black Muslims accused Malcolm of betrayal. “Such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death,” Louis X, now known as Louis Farrakhan, proclaimed in December 1964. Weeks later, on February 21, 1965, assailants affiliated with the NOI assassinated Malcolm X in Harlem.

Malcolm X has been the subject of several biographies, the most recent and comprehensive of which is Manning Marable’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. Marable’s mission was to “go beyond the legend; to recount what actually occurred in Malcolm’s life.” He pursued that aim earnestly, probing the whole of his subject’s story, personal and public, no matter how embarrassing the findings. He recounts Malcolm X’s secret 1961 meeting with representatives of the Georgia Ku Klux Klan to discuss their shared insistence on racial separation. He notes that at a few NOI rallies Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad hosted George Lincoln Rockwell of the American Nazi Party. In Marable’s telling Elijah Muhammad believed himself divinely omniscient, directed Malcolm X to pay tribute, prohibited him from working with civil rights activists, and even prevented him from confronting Los Angeles police who had maimed and killed members of the NOI. Elijah Muhammad’s manipulations extended to all his deputies: he insisted that ministers desist from buying life insurance so that they would be all the more subservient out of fear for their families in the event of their incapacitation or death.

According to Marable, jealousy, enmity, pettiness, and corruption poisoned the inner circle of the NOI. He describes NOI officials beating followers as a mode of discipline and demanding increased tithes to pay for personal extravagances, such as luxury automobiles. He maintains that Malcolm X’s marriage to Betty Shabazz was a loveless affair, marked by neglect (his) and infidelity (hers). He claims that “circumstantial but strong evidence” suggests that at least once Malcolm X indulged in a paid homosexual liaison. He confirms Malcolm X’s allegations that Elijah Muhammad, while married, seduced young followers, got them pregnant, and then abandoned them and their children, all the while preaching the virtue of chastity and patriarchal duty.

Marable’s provides abundant resources from which to draw for purposes of castigating Elijah Muhammad, the NOI, and Malcolm X. Many of these ugly facts had been previously uncovered by other researchers, but none had Marable’s academic stature or political credentials. Marable was the founding director of the Columbia University Institute for Research in African American Studies and was an important, well-respected figure among left black activist intellectuals. His candor is impressive; he must have known it would provoke accusations of rank betrayal. He certainly understood that some admirers and apostles of Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad would berate him for publishing material that hurts the reputation of twentieth-century black nationalism, and would claim that he was doing so opportunistically while feeding off of white, elite institutions—Columbia University and the Viking Press publishing house—that are largely unaccountable and indifferent to black folk.

These and other allegations and insinuations can be found in two compilations of essays, A Lie of Reinvention: Correcting Manning Marable’s Malcolm X (2012), edited by Jared A. Ball and Todd Steven Burroughs, and By Any Means Necessary: Malcolm X: Real, not Reinvented—Critical Conversations on Manning Marable’s Biography of Malcolm X (2012), edited by Herb Boyd, Ron Daniels, Maulana Karenga, and Haki Madhubuti. While the latter collection contains several instructive essays, the former is uniformly tendentious, with piece after piece asserting not just that Marable is mistaken or negligent but that he knowingly spreads falsehoods. “More than merely viewing Marable’s reinvention of Malcolm as false,” Ball writes, “we have, beginning with our choice of book title, unapologetically laid down our claim that it is a lie.”

These overheated ad hominem attacks lack substantiation. Those who accuse Marable of lying fail to adduce credible evidence. They cavalierly fling charges that should only be made with care.

They are also wrong in another way. They maintain that Marable fails to accord Malcolm X sufficient credit. Actually, though, he gives the man too much credit. Marable remains enmeshed in the Malcolm X legend. He declares in the final sentence of his biography that “Malcolm embodies a definitive yardstick by which all other Americans who aspire to a mantle of leadership should be measured.” Yet Marable’s narrative indicates that Malcolm X was actually a poor leader, subject to all manner of bad ideas, who constantly misjudged people and events. For most of his post-prison life, he was the mouthpiece for a theocrat who, claiming access to divine revelation, propagated an escapist, socially conservative (e.g., anti–birth control) black nationalism that was sexist in its subordination of women and racist in its condemnation of whites.

Elijah Muhammad’s racial teachings must be recalled with particularity. To him, not some whites but all whites were “devils,” doomed by their race to be evildoers. In Message to the Blackman in America (1965), he insists, “The origin of sin, the origin of murder, the origin of lying are deceptions originated with the creators of evil and injustice—the white race.” Whites, he writes, “cannot produce good for they are without the nature of good.” “None of them are righteous—no not one,” he proclaims. “They are ever seeking to do harm to [blacks] every second of the day and night.” Angered and disgusted by “the most wicked and deceiving race that ever lived on our planet,” he foresaw and eagerly anticipated the destruction of whites. Nothing else could bring relief because “as long as the devil is on our planet we will continue to suffer injustice and unrest and have no peace.” But deliverance is coming, The Messenger prophesies: “The guilty who have spread evilness and corruption throughout the land must face the sentence wrought by their own hands.”

Malcolm X dutifully echoed his spiritual master, albeit with élan and greater attentiveness to current events, domestic and international. A good example of Malcolm X ’s oratory as a NOI minister is his address “Message to the Grassroots,” delivered in Detroit at the King Solomon Baptist Church in November 1963. In it he expressed his disgust at the government’s broken promises with an uninhibited candor that many blacks found thrilling.

The speech was one of the last Malcolm X delivered prior to leaving the NOI, and, in it, he voiced signature themes. One is the need to recognize the shared adversary: “Once we all realize that we have a common enemy, then we unite . . . . And what we have in common is that enemy—the white man. He’s the enemy to us all.”

A second theme is the importance of a united black front free of white influence. “We need,” Malcolm X declared, “to stop airing our differences in front of the white man, put the white man out of our meetings, and then sit down and talk shop with each other.” Railing against what he saw as the dilutive effect of white participation in the Civil Rights Movement, he turned to mockery: “It’s just like when you’ve got some coffee that’s too black, which means it’s too strong. What do you do? You integrate it with cream, you make it weak.” It was because of the need to accommodate whites that the March on Washington “lost its militancy. It ceased to be angry, it ceased to be hot, it ceased to be uncompromising. Why, it even ceased to be a march. It became a picnic, a circus. Nothing but a circus, with clowns and all. . . . it was a sellout.”

A third, related, theme is the absence of authentic black leaders accountable to black folk. The white man, Malcolm X charged, “takes a Negro, a so-called Negro, and makes him prominent, builds him up, publicizes him, makes him a celebrity,” and then foists him upon blacks as a leader. The white man then uses these manufactured Negro leaders “against the black revolution.”

Just as the slavemaster . . . used Tom, the house Negro, to keep the field Negroes in check, the same old slavemaster today has Negroes who are nothing but modern Uncle Toms, twentieth-century Uncle Toms, to keep you and me in check, to keep us under control, keep us passive and peaceful and nonviolent.

What caused the most excitement and earned the most denunciation was Malcolm X’s observation regarding violence. “If violence is wrong in America,” Malcolm X thundered, “violence is wrong abroad. If it is wrong to be violent defending black women and black children and black babies and black men, then it is wrong for America to draft us and make us violent abroad in defense of her.” Before King and others related domestic race relations to U.S. foreign policy, Malcolm X did so.

He also reproached blacks for what he saw as their failure to defend themselves adequately. “You bleed for white people,” he said. “But when it comes to seeing your own churches being bombed and little black girls murdered, you haven’t got any blood. . . . How are you going to be nonviolent in Mississippi, as violent as you were in Korea?” As for the philosophical nonviolence insisted upon by King and others, Malcolm X was downright contemptuous. “Whoever heard of a revolution where they lock arms . . . singing ‘We Shall Overcome’? Just tell me. You don’t do that in a revolution. You don’t do any singing, you’re too busy swinging.”

While Malcolm X and other followers of Elijah Muhammed put on cathartic performances in safe surroundings, however, King, Carmichael, Medgar Evers, John Lewis, Fannie Lou Hamer, James Farmer, Julian Bond, Bob Moses, Diane Nash, James Lawson, and others risked their lives repeatedly in face-to-face confrontations with heavily armed, trigger-happy white supremacists. While Malcolm X was taunting King and company for rejecting violence, the tribunes of the Civil Rights movement were successfully pressuring the federal government to bring its immense weight to bear against the segregationists through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. While Malcolm X talked tough—“if someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery”—he and the NOI refrained seeking revenge when racist police brutalized Black Muslims. While Malcolm X spoke with apparent knowingness about racial uplift, at no point did he communicate a cogent, realistic strategy for elevating black America.

Farmer, of the Congress of Racial Equality, unmasked the emptiness of Malcolm X’s thinking during a debate in 1962. “We know the disease, physician,” he said, “what is the cure? What is your program and how do you hope to bring it into effect?” At a loss for anything pertinent to say, Malcolm X chastised Farmer for having married a white woman.

Marable emphasizes that Malcolm X displayed a remarkable capacity for growth and reinvention, especially during his final year of life. Tragically, however, he was murdered by former comrades before his transformation could fully develop. In subsequent decades, propagandists, activists, politicians, rappers, and filmmakers have remade Malcolm X, portraying him as a figure who rivaled King in vision and achievement. By downplaying Malcolm X’s complicity in spreading a morally bankrupt and socially backward ideology, by exaggerating the significance of that final year, and by failing to examine more searchingly Malcolm X’s proposals, Marable contributes to this mythology. He accords to his hero a stature in memory that he lacked in history.

Stokely Carmichael

While Malcolm X is the most celebrated figure in the black power line of African American protest, Stokely Carmichael occupies a unique place as the person who popularized the “black power” slogan.

His key intervention came on June 16, 1966, during the March Against Fear, which had been initiated by James Meredith, the black man who broke the color barrier at the University of Mississippi. Meredith had planned to walk alone from Memphis to Jackson to dramatize the determination of blacks to exercise freedoms long denied them. After a white man shot and wounded Meredith on the second day of his trek, Carmichael joined activists from across the Civil Rights Movement to resuscitate the effort. Along the way, Carmichael was jailed for defying an order against raising tents to shelter marchers on the grounds of a black public school. Upon release, Carmichael declared, the “only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin’ us is to take over. We been saying ‘freedom’. . . and we ain’t got nothin’. What we gonna start sayin’ now is ‘black power’!” The crowd responded with exhilaration: “Black Power! Black Power! Black Power!”

Carmichael joined the March Against Fear as the newly elected chair of SNCC. Born in Trinidad in 1941, raised in New York City, and introduced to serious political activism at Howard University, Carmichael was part of that remarkable cadre of reformers whom Howard Zinn called “the new abolitionists” and whom Jack Newfield dubbed the “prophetic minority.” He joined in freedom rides, sit-ins, and voter registration drives. He canvassed places in the Deep South where “uppity Negroes”—that is, blacks who sought to take advantage of their rights as American citizens—were murdered with impunity. On his twentieth birthday he found himself incarcerated in Mississippi’s infamous Parchman Prison for entering a white waiting room in a train station in Jackson. When he and his associates climbed out of a paddy wagon, an officer drawled, “We got nine: five black niggers and four white niggers.” By the time of the March Against Fear, Carmichael had been jailed at least two-dozen times.

Peniel Joseph’s biography, Stokely: A Life, is an admiring depiction of a brave, handsome, talented, well-spoken man who gave himself unstintingly to the Civil Rights Movement during its most glorious years in the early 1960s. The key moment for Carmichael, Joseph agrees, is the evening he shouted “black power” to that crowd in Mississippi:

by his ambition, stood at the center of this storm deploying provocative rhetoric with passion and eloquence. He instantly commanded the space previously occupied by Malcolm X, assassinated sixteen months earlier.

After that Carmichael became a celebrity. He was invited onto television programs such as Meet the Press and Face the Nation and was profiled in Time. He was vilified by politicians seeking the support of anxious or angry white voters and invited to speak at colleges and universities.

Working in the Deep South with his comrades in SNCC prior to black power—figuring out how to present to the nation the lawless oppression that blacks endured and experimenting with methods for raising the political consciousness of African American serfs—Carmichael distinguished himself in an inspiring campaign of social justice. His colleagues admired his dedication, persistence, idealism, loyalty, and courage. As he rose in prominence, however, the quality of his character, political and personal, deteriorated.

Although SNCC was already in decline when Carmichael was elected to head it in 1966, he failed to slow its descent and probably accelerated it. Carmichael’s predecessor as chair was John Lewis, a remarkable figure then who has only become more extraordinary over the years during his tenure as a Democratic member of the Georgia congressional delegation. Lewis’s reelection as chair initially appeared pro forma. But some in SNCC complained that he was insufficiently militant and too much of an interracialist. They wanted to assert a right to respond to violence with violence; they thought SNCC should be run by and for blacks; and they insisted that whites exercise negligible, if any, influence within the organization. Though Lewis was at first re-elected, opponents challenged the ballot, and Carmichael prevailed in a recount. The awkward reversal poisoned Lewis’s relationship with Carmichael. Soon the triumphant militants ran away the whites on SNCC’s staff.

According to Joseph, “Carmichael used his one-year tenure as SNCC Chairman to thrust himself into the stratosphere of American politics.” He hobnobbed with the heads of the other leading civil rights organizations—Farmer, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, Whitney Young of the National Urban League and, of course, King. He socialized with activist entertainers such as Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba, whom he later married. He interacted, too, with important white politicians, often refusing to abide by conventional standards of decorum: he spurned a White House invitation and declined to shake the mayor of Atlanta’s outstretched hand.

The more defiant Carmichael’s actions, the more provocative his rhetoric, the more attention he received. This fed his ego but did little to buoy SNCC’s sagging fortunes, a fact that did not escape the notice of colleagues who began to deride him as “Stokely Starmichael.” “SNCC’s organizational strength seemed to decline,” Joseph maintains, “in proportion to Carmichael’s growing fame.” Rather than seek a second term as Chair, Carmichael turned the leadership of SNCC over to H. Rap Brown, who fecklessly presided over the organization’s quickening slide. In an ugly spectacle, SNCC tore itself apart, pathetically betraying the racial unity its leaders trumpeted. In the summer of 1968, it expelled Carmichael.

After a dalliance with the Black Panther Party, including as its honorary prime minister, Carmichael journeyed abroad where he was received as an esteemed revolutionary in some quarters and established the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party, which never amounted to much. Eventually he settled in Guinea, where he changed his name to Kwame Turé in homage to Kwame Nkrumah, the deposed first president of Ghana, and Sekou Turé, Guinea’s dictatorial president. Stricken by prostate cancer, Carmichael/Turé died in Guinea on November 15, 1998.

Joseph has studied black power deeply, producing a series of well-regarded articles and books including, most notably, Waiting ’til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (2006). His biography of Carmichael, however, is not nearly as informative as it should be. Joseph stresses that Carmichael was a skillful and effective organizer in the Deep South during his early days with SNCC. Missing, however, is a detailed rendering of what being an organizer meant. What did Carmichael say to vulnerable black farmers he sought to bring into the political process? How did he earn their confidence and respect? What did he do day by day?

Joseph relies upon confidently asserted adjectives, usually flattering ones, to do what should be done by careful, patient, and detailed exposition. For instance, he describes Carmichael’s 1966 New York Review of Books essay “What We Want” as “brilliant.” According to Joseph, “‘What We Want’ intellectually disarmed some of Carmichael’s fiercest critics and in the process announced SNCC’s Chairman as a formidable thinker.” Joseph neglects, however, to identify the critics to whom he refers, the criticisms to which he alludes, or, most importantly, the reasons why an observer ought to agree with his attribution of brilliance. He quotes a passage from Carmichael’s essay:

For too many years, black Americans marched and had their heads broken and got shot. They were saying to the country, ‘Look, you guys are supposed to be nice guys and we are only going to do what we are supposed to do—why do you beat us up, why don’t you give us what you ask, why don’t you straighten yourselves out?’ After years of this, we are at almost the same point—because we demonstrated from a position of weakness. We cannot be expected any longer to march and to have our heads broken in order to say to whites: come on, you’re nice guys. For you are not nice guys. We have found you out.

Is this brilliant? Not self-evidently so.

Joseph spends less than two pages on the most important of Carmichael’s writings: Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (1967), coauthored by political scientist Charles Hamilton. According to Joseph, Black Power is a “still-powerful diagnosis of America’s tortured racial history” and “an intellectually rigorous and theoretically subtle political treatise whose unexpected breadth and depth surprised critics.” Joseph, however, offers no detailed and sustained description of Black Power. “Carmichael and Hamilton offered an alternative reading of American history,” Joseph writes. “They replaced optimistic narratives of democratic ascent with the reality of racial oppression, white violence, and a national failure on racial matters.” But a summary so abstract offers readers little insight into Black Power’s contribution to the literature produced by the civil rights revolution. Joseph notes that Black Power was reviewed in several magazines and newspapers upon publication. That is useful. But what have commentators said about Black Power over the past four decades? And how does the book look in comparison with the writings of others and in light of subsequent developments? Answers are not to be found in Stokely.

Joseph discusses Lewis’s ouster from the chairmanship of SNCC all too briefly. Devoting less than a page to this episode, Joseph alludes to it as if readers should be so familiar with the dispute that further elaboration isn’t needed. I have my doubts. Moreover, whether or not readers are familiar with it, the contest between Lewis and Carmichael was so important and remains sufficiently divisive that it warrants comprehensive evaluation. In Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement (1998), Lewis spends an entire chapter on the disputed election. In Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (2003), Joseph’s hero offers a very different story. Which account is more credible? Is there a synthesis superior to both? Again, Joseph offers no guidance.

Huey Newton

In 1966, in Oakland, California, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale set in motion what became the Black Panther Party. Newton was a child of the Great Migration. He was born in 1942 in Monroe, Louisiana, the youngest of seven, and moved to Oakland in 1945. His parents were drawn by the prospect of economic opportunities stemming from the World War II industrial boom. In the early ’60s, Newton attended Merritt College, where he met Seale. Seale was also a migrant—born in Dallas in 1936 and raised in Oakland in a working-class family. He did a stint in the Air Force before enrolling at Merritt where, along with Newton, he immersed himself in roiling debates about black history, socialism, black nationalism, integration, and anti-colonialism.

Frustrated by continuing racial subordination notwithstanding the apparent victories of the Civil Rights Movement, Newton and Seale decided to express themselves in a fashion that would appeal first and foremost to the “brothers on the block.” Their audience comprised working- and lower-class blacks who were impatient with appeals to the conscience of the white establishment and who hungered instead for an assertive, defiant politics, a politics that expressed demands for black power not only in rhetoric but in deed. Newton and Seale objected to the entire gamut of obstacles and disabilities that burdened poor urban blacks. The scope of their discontent, the depth of their ambition, and the radicalism of their methods can be seen in the most impressive writing they produced—the “Ten Point Program” that served as a platform for the newly formed Panthers. “To those poor souls who don’t know Black history, the beliefs and desires of the Black Panther Party may seem unreasonable,” Newton and Seale wrote. But “to Black people, the ten points covered are absolutely essential to survival.” Echoing calls for “Freedom Now,” the program complained that Blacks “have listened to the riot producing words ‘these things take time’ for 400 years.” Newton and Seale itemized “What We Want”:

1. We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our black and oppressed communities.

2. We want full employment for our people.

3. We want an end to the robbery by the capitalists of our Black and oppressed communities.

4. We want decent housing, fit for the shelter of human beings.

5. We want decent education for our people that exposes the true nature of the decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society.

6. We want completely free health care for all Black and oppressed people.

7. We want an immediate end to police brutality and murder of Black people, other people of color, all oppressed people inside the United States.

8. We want an immediate end to all wars of aggression.

9. We want freedom for all Black and oppressed people now held in U.S. Federal, State, County, City and military prisons and jails. We want trials by a jury of peers for all persons charged with so-called crimes under the laws of this country.

10. We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, peace and people’s community control of modern technology.

The program is an arresting synthesis. It echoes the ten-point platform that Malcolm X created for the Nation of Islam in 1963. It also expressly invokes the most iconic documents of the United States, repeatedly alluding to the Constitution, particularly the Second Amendment right to bear arms. The program concludes with the prologue to the Declaration of Independence.

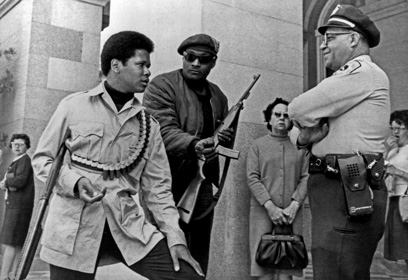

Newton and Seale chose as their key issue police misconduct, especially the use of excessive force. They borrowed a tactic other activists had deployed after instances of police misconduct. They would follow and observe Oakland cops, all the while carrying loaded firearms publicly, which state law then permitted them to do. Although this tactic prompted confrontations with police, Newton and Seale refused to back down. They believed that routine humiliation and brutalization by police epitomized blacks’ racial subordination, and they insisted that blacks had a right to defend themselves against police misconduct.

Three confrontations with police in 1967 forged the Panthers’ reputation. In January a contingent led by Newton entered the lobby of the San Francisco airport. In Black Against Empire, Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr. write that the Panthers were “dressed in uniform—waist-length leather jackets, powder blue shirts, and black berets cocked to the right.” The men displayed shotguns and pistols—again, legally. They had come to the airport to receive Betty Shabazz, the widow of Malcolm X, and to escort her to an interview with an ex-convict journalist writing forRamparts magazine, Eldridge Cleaver. At the Ramparts office, Newton got into an altercation with a reporter. According to Bloom and Martin:

Police officers reacted, several flipping loose the little straps that held their pistols in their holsters. One started shouting at Newton who stopped and stared at the cop. Seale tried to get Newton to leave. Newton ignored him and walked right up to the cop. ‘What’s the matter,’ Newton said, ‘you got an itchy finger?’

The cop made no reply and simply stared Newton in the eye, keeping his hand on his gun and taking his measure. The other officers called out for the cop to cool it, but he kept staring at Newton. ‘O.K. you big fat racist pig, draw your gun,’ Newton challenged. The cop made no move. Newton shouted, ‘Draw it, you cowardly dog!’ He pumped a round into the shotgun chamber.

The other officers spread out, stepping away from the line of fire. Finally, the cop gave up, sighing heavily and hanging his head. Newton laughed in his face as the remaining Panthers dispersed.

A second episode, in May, earned the Panthers their first brush with national media attention. A group of uniformed Panthers entered the California capitol building with their firearms in full view to denounce proposed legislation that, if enacted, would outlaw the carrying of loaded guns in public. Bloom and Martin portray this demonstration as profoundly significant:

The Sacramento protest attracted a wider movement audience and established the Black Panther Party as a new model for political struggle. Soon students at San Francisco State College and the University of California, Berkeley flocked to Panther rallies by the thousands. Countless numbers of young blacks—looking for a way to join the ‘Movement,’ or just to channel their anger at the oppressive conditions in which they lived—now had a political organization they could call their own.

Finally, on the evening of October 27, Newton killed an Oakland police officer, John Frey. Newton was charged with murder and convicted of manslaughter, though his conviction was overturned on appeal. Two retrials ended with hung juries. The “Free Huey” campaign made Newton one of the most publicized inmates of the 1960s.

Bloom and Martin maintain, “From 1968 through 1970, the Black Panther Party made it impossible for the U.S. government to maintain business as usual, and it helped create a far-reaching crisis in U.S. society.” For substantiation, they turn to a witness on the left, the Students for a Democratic Society, which called the Panthers the “vanguard in our common struggles against capitalism and imperialism.” They also turn to a witness on the right, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who in 1969 declared, “The Black Panther party, without question, represents the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” Indeed, according to Bloom and Martin, the Panthers’ impact did not stop at the border, as the party “forged powerful alliances, drawing widespread support . . . from anti-imperialist governments and movements around the globe.” “Without the Black Panther Party,” Bloom and Martin insist, “we would now live in a very different world.”

The authors are unabashed in their admiration for the Panthers. They praise the Panthers’ revolutionary aspirations—their demand for a new, post-capitalist, anti-racist social order as opposed to integrationist reformers who merely wanted a larger piece of the American pie. They laud the Panthers’ willingness to confront police in word and practice. They applaud the party’s efforts to suppress homophobia and sexism within its own ranks. They acclaim the Panthers’ efforts to feed children through a much-heralded breakfast program and to make accessible to poor people much-needed medical care. They commend the Panthers for having been more cosmopolitan and open to interracial coalitions than were other champions of black power in the late ’60s, for having been more radical than the establishment’s favorite organs of civil rights protest, for having opposed U.S. foreign policy even in a time of war. They rightly note that the party was the victim of a ruthless campaign of suppression by local, state, and federal officials. Its ranks were infiltrated by government agents and its members abused by police. Making a mockery of legal protections for freedom of expression and association, the FBI sought to turn local constituencies against the Panthers and tried, sometimes with deadly effectiveness, to turn Panthers against themselves and other radicals.

As they go about correcting what they perceive as misimpressions that minimize the Panthers’ significance and sully their character, Bloom and Martin accuse several historians of having “effectively advanced J. Edgar Hoover’s program of vilifying the Party and shrouding its politics.” These detractors “omit and obscure the thousands of people who dedicated their lives to the Panther revolution, their reasons for doing so, and the political dynamics of their participation, their actions, and the consequences.”

But Bloom and Martin’s effort to rehabilitate the Panthers’ reputation founders on tendentious advocacy. Read again their description of the confrontation at the Ramparts office. It wholly indulges the Panthers’ portrayal of what transpired. In another depiction of Newton and Seale facing down Oakland cops, Bloom and Martin have Newton pushing a policeman out of a parked car, leaping out of the vehicle with shotgun in hand, and shouting, “Now, who in the hell do you think you are, you big rednecked bastard, you rotten fascist swine, you bigoted racist? . . . Go for your gun and you’re a dead pig.”

This reads like a script from a Melvin Van Peebles film—in other words, a fantasy in which Newton is the swashbuckling hero who mouths all of the baddest lines. But how do Bloom and Martin know that Newton whipped the cop and then called him a “rednecked bastard”? “The description of the event,” they declare in their endnotes, “comes from Bobby Seale, Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton . . . and from Joshua Bloom’s tour of the site of the incident with Bobby Seale.” Seale’s memoir is certainly a pertinent source, but one that a responsible historian would handle skeptically, on guard for bias and inaccuracy. It must be corroborated before its claims can be represented as fact.

Bloom and Martin, however, make little effort to look beneath the swaggering veneer of Panther reminiscences. In Reviews in American History, historian Jama Lazerow notes that, in Black Against Empire, “It is not clear just what constitutes historical proof.” Writing in the Los Angeles Times Book Review, Héctor Tobar observes that Bloom and Martin’s “most dramatic failing” is “their lack of critical distance from their subjects. . . . Many passages read as if they were written in the pages of the Panthers’ official publication, ‘The Black Panther,’ circa 1970.”

Bloom and Martin also produce little evidence or sustained argument to support their assertions of the Panthers’ significance. Here is a characteristic formulation: “For a few years, the Party seized the political imagination of a large constituency of young black people.” What do they mean by “large”? Thirty percent of black people between the ages of eighteen and fifty in the late ’60s or early ’70s? Forty percent? They don’t say.

They further maintain that by 1970 “what was once a scrappy local organization was now a major international political force, constantly in the news, with chapters in almost every major city.” It is true that the Panthers were “constantly in the news.” But was that media presence an accurate reflection of their activity and influence, or a reflection of journalists’ hunger for the sensational (albeit marginal)? Perhaps both, but Bloom and Martin fail to examine the matter carefully.

At one point, they do attempt to inject some quantitative specificity into their narrative. By 1970, they write, the Panthers “had opened offices in sixty-eight cities,” that “the Party’s annual budget reached about $1.2 million (in 1970 dollars),” and that the “circulation of the Party’s newspaper . . . reached 150,000.”

While this is an improvement over vague adjectives (“large,” “major”), Bloom and Martin never subject their evidence to rigorous analysis. The Panthers may have opened sixty-eight offices, but what constituted an office? A post office box, two conveners, and a casual nod from party authorities in Oakland? Bloom and Martin don’t say. This proliferation of offices may signal far less than they imply. As for the $1.2 million budget, that figure would be more meaningful if compared to the budgets of, say, the SCLC, NAACP, and other black defense and uplift organizations. Sociologist Herbert Haines generated useful insights by pursuing such comparisons in Black Radicals and the Civil Rights Mainstream, 1954–1970 (1988). He found that the NAACP and kindred organizations were even more attractive to donors thanks to militant activism: “moderate groups . . . profited immensely from the pressure created by more radical groups and rebellious ghetto-dwellers.” In light of Haines’s research, one might investigate whether the Panthers exerted a notable influence as a threat even when their own activity was negligible. Yet here, as elsewhere, Bloom and Martin fail to pursue potentially fruitful inquiries. As Fabio Rojas writes acidly in The American Historical Review, Black Against Empire “shies away from the most important question about the Black Panther Party.”

Bloom and Martin rightly criticize writings that tendentiously assail the Panthers, pay little heed to the inequities they sought to remedy, the repression they faced, and the benefits they bestowed. Bloom and Martin especially loathe the work of David Horowitz, a leftist who became a conservative in part out of disgust with the party. They also cite The Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America (1994), by Hugh Pearson, who was, when he authored that book, an editorial writer for the Wall Street Journal. The Shadow of the Panther chronicles a long and lurid list of legal and moral crimes, including extortion, drug trafficking, and murder. To Bloom and Martin, Horowitz and Pearson are simply continuing Hoover’s vilification of the Panthers.

Detractors, however, would be hard pressed to sow more suspicion than Bloom and Martin themselves do. They write, for example, that Newton’s “street knowledge helped put him through college, as he covered his bills through theft and fraud.” Nothing is said about what Newton did, the identities of those hurt, or the extent of their losses. Far from criticizing Newton, Bloom and Martin leaven their description with a hint of esteem, noting, “When Newton was caught, he used his book knowledge to study the law and defend himself in court, impressing the jury and defeating several misdemeanor charges.” Later, Bloom and Martin consign the killing of Frey, a key event in the history of the Panthers, to obscurity. “There are conflicting accounts of what happened,” they say, but they do not describe those accounts and thus leave readers without guidance as to which ought to be believed and why.

Bloom and Martin mention that Newton fled to Cuba after being indicted in 1974 for killing a seventeen-year-old prostitute and beating a man. But again they forgo exploring the circumstances surrounding these allegations, insinuating that the charges were meant to demonize Newton and the Panthers. On the other hand, they concede, albeit grudgingly, there is reason to believe that “for much of the 1970s, Newton ruled the Party through force and fear and began behaving like a strung-out gangster.”

If Bloom and Martin refer to Newton as a gangster, his misdoings must have been awful indeed, for they hold to a minimum any information or conclusions that reflect badly on the Panthers. They relegate to a mere clause in a sentence the sensational fact that in 1973 Newton expelled Seale from the party. Excessively condensed, as well, is their rendition of the sad story of Newton’s end. With conspicuous terseness, they note simply that on August 23, 1989, he was killed by “a petty crack dealer from whom he was likely trying to steal drugs.”

• • •

In assessing Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and Huey Newton it is important to keep in mind that they tried to act against the racial injustice that has befouled America. That alone entitles them to some respect. It is important to acknowledge, too, the profound obstacles they encountered within and outside black communities. At this moment when civil liberties are threatened by new, disturbingly powerful surveillance technologies, we must remember that the self-destructive paranoia and divisiveness that menaced black power leaders stemmed in large part from the devious and illicit machinations of Hoover and other enforcers of law and order.

It is also important to acknowledge that Carmichael was only twenty-five when he shouted “black power!” and that Newton was only twenty-four when, with Seale, he founded the Panthers. It should come as no surprise that young people sometimes display bad judgment in confronting daunting conditions. Without a sympathetic appreciation of peoples’ problems, internal and external, there is no realistic way to take stock of their accomplishments and defeats.

But this does not lessen the responsibility of scholars to be exacting, especially when they self-consciously pursue their studies in order to advance social change, as the progressive revisionists of black power do. The art of social transformation is demanding. Those who portray the past for instruction and inspiration must not shrink before its imperatives, lest today’s activists learn the wrong lessons.