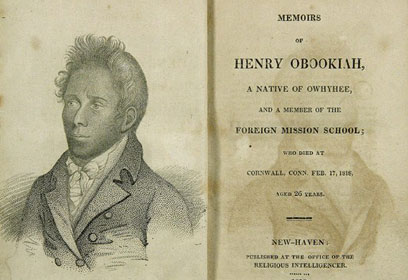

The frontispiece from the Memoirs of Henry Obookiah, published 1818. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The frontispiece from the Memoirs of Henry Obookiah, published 1818. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.John Demos

Knopf, $30 (cloth)

Great failure is often more enduring than we realize. Before the downward spiral, the effort seems to cast the future in its image. It captures a moment and then goes uncommemorated. Yet it does not go away. It is as if the hopes it once contained continue to smolder.

The Paris Commune, the revolutionary socialist government that ruled the French capital in the spring of 1871, was such a failure: virtually erased from the public memory of modern Paris, but an inspiration to generations of socialists before the Russian Revolution and a corresponding source of fear for their opponents. Another such failure was the Foreign Mission School of Cornwall, Connecticut, the subject of John Demos’s new book, The Heathen School, freshly longlisted for the 2014 National Book Award.

The comparison, I concede, seems grandiose. The Commune left thousands, possibly tens of thousands, dead and large swaths of Paris in ruins. The Foreign Mission School destroyed only itself, leaving disillusioned graduates and an embittered and divided local community that threatened, but never executed, violence. It did its damage at a distance.

What unites the Commune with the Foreign Mission School is the bright and defining hope each originally contained and the disappointment each eventually produced. The Commune was a moment when France seemed to augur a new day; the school embodied equivalent optimism for the United States. Cornwall was a visible world of farms, forests, and villages but also an invisible world where God and Satan contested. God’s victory would be America’s gift to posterity.

The Heathen School, as it was called in everyday speech, became an American exercise in revolutionary uplift designed to transform the vast non-Christian world into something that looked like Connecticut. Instead of sending missionaries to the heathen, the school brought the heathen to the missionaries. The school would transform young men into Christians able to become missionaries or to assist them. It was part of an American project to spread republicanism and Protestant Christianity—for Americans regarded the two as inextricably linked—across the globe.

Demos possesses an uncanny ability to see the reflection of a much larger world in the towns of colonial New England and the early republic. In The Heathen School, what Demos discerns is American exceptionalism: the proposition that the United States is a chosen nation whose history diverges from all others and whose destiny will determine the fate of the world. It is an idea still embraced by most American politicians (even when they are smart enough not to believe it) and loathed by most American historians.

Extravagant ideas can alight on modest places. Cornwall is a small town in what was, during the early nineteenth century, the heartland of a New England evangelicalism determined to change the world. Some of the locals were articulate proponents of American exceptionalism and made it the rationale for the school. The United States was, according to Yale College President Timothy Dwight, the place where “Empire’s brightest throne shall rise.” Lyman Beecher of Connecticut—the father of Henry Ward Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, who followed the reforming zeal of evangelicalism into abolition—already knew the answer when he asked, “From what nation shall the renovating power go forth?” There was less a fine line between American benevolence and American imperialism than no line at all.

Today as before, we tend not to look closely at the societies we expect to transform.

It later became a cliché that Protestant missionaries to Hawaii, including those associated with the Heathen School, “came to do good and did well,” but the original enthusiasm for uplift was genuine. These were people who thought the millennium might be at hand. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Mission, sponsors of the Foreign Mission School, reversed the connections between expanding American trade and spreading the Gospel. “Natives of almost every heathen country” were being drawn from their homes by American commerce, the Board said. If not converted, they would bring the worst of American society back to their lands, corrupting their countrymen and prejudicing them against Christianity. The Foreign Mission School would take non-Christians drawn to the United States by commerce, or those who already lived within its boundaries, educate them, convert them, and send them home to transform their homelands.

The school was thus ancestral to a variety of American projects designed to make foreigners into instruments of conversion, people who would turn their countrymen into people like us. Our current rationale in training military officers and economists is not so different than that for training missionaries. As the sponsors of the Heathen School knew, the results could be disappointing. Frequently, they still are, unless you consider the likes of General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and Mohamed Morsi, both partially educated on American shores, successful at creating New England in Egypt.

• • •

We tend not to look closely at the societies we expect to transform. We collapse them into largely undifferentiated lumps. This is true now as it was then. The very term Heathen School conveyed the American sense of a vast, indistinguishable mass of non-Christians. The students who came to the school were, however, disparate. Hawaiians dominated the first class, but it also included an Abenaki Indian, a Bengali, and a man named John Johnson, whose father was the child of an “English gentleman” and a “Hindoo woman” and whose mother was “a Jewess of the race of black Jews.” Later Tahitians came, as did at least one more Jew, a student from Timor, a Malay held as a slave in China, a Chinese, and two Greek boys from Malta. The students came from the four corners of the earth, but they were heathens one and all.

Demos breaks the undifferentiated mass into particular people. He concentrates on a small set of individuals—Henry Obookiah, who was Hawaiian, John Ridge and Elias Boudinot, both of whom were Cherokees from Georgia, and Sarah Bird Northrup and Harriet Gold, who were from Cornwall. The desire for salvation ran together with more earthly ones. The result is a book as much about psychology as theology and as much about intimacy as commerce.

In Demos’s books people who think they control events find themselves shaken by those supposedly under their influence. But the Hawaiian Henry Obookiah, who both in a sense created the Heathen School and was its chief product, was not the challenge that brought the imperial dream down.

Events far from New England uprooted Obookiah and deposited him in Connecticut. The internal wars that yielded the kingdom of Hawaii orphaned Obookiah, and the China and Pacific trade, of which the Hawaiian Islands were an integral part, set him in motion. He became a Kanaka, an expatriate Hawaiian sailor, who made his way to New England and arrived at Yale in search of an education. In Demos’s interpretation he was in search of family; he thought he found it in Connecticut.

Obookiah underwent a classic Protestant conversion experience and came “home to New Jerusalem,” entering the church on April 9, 1815. It was Obookiah who formulated a plan to return to Hawaii “to preach the Gospel to my Countrymen” in their own language. He became the most celebrated of the group of Hawaiians who formed the nucleus of the Foreign Mission School’s first class. It was, the American Board believed, the hand of providence that brought Obookiah to Connecticut. The founders felt “confident that this thing is from God . . . [and] will, among others, be a means of evangelizing the world.” Obookiah did seem to be the real thing. He invented orthography for writing Hawaiian, learned Hebrew, and grew famous, which proved useful for raising money and advancing the cause.

Obookiah died of typhus in 1818, one of those fortunate deaths that frees a person from responsibility for failures to come. As was the custom, his deathbed scene was fully described and his words recorded. Lyman Beecher preached his eulogy. His ghostwritten Memoirs would go through “about a dozen editions,” according to Demos. His goals, though, were largely unfulfilled. In Hawaii the missionaries, accompanied by several of the graduates of the Foreign Mission School, made converts, but the students were by and large a disappointment. In time the Americans took over the islands, enriched themselves, and largely dispossessed the inhabitants, who dwindled in numbers.

When Obookiah died the Hawaiian missionaries had not yet departed, nor had John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and the other Cherokee students arrived at the Heathen School. After 1818 American Indians would dominate the student body. There was tension between the Indians and the Pacific Islanders; there were issues with truancy, discipline, and uneven academic achievement. But most troubling were relationships between the Cornwall girls and the scholars, or, as officials put it, “the colored boys.”

The desire to save the Indians, and a long history of sexual relations between Indian women and white men, did not prepare Cornwall for consensual sexual relations—in or out of marriage—between its white women and the school’s Indian men. To many readers, this will not come as a surprise, but the history of interracial sex is far more complicated than most Americans believe, and even more complicated than Demos makes it here. In the nation’s first days, it was fairly common and, if not fully accepted in all configurations, not routinely condemned or punished. But as the nineteenth century went on, prejudices against what became known as miscegenation intensified and hardened. The end of slavery—and with it the guaranteed subordination of black men and the coerced availability of black women—alongside worries about inheritance and property transmission and changing ideas about race all made interracial sex less tolerated than it had been earlier in American history. In Cornwall signs of this resistance appeared early.

John Ridge was from a leading Cherokee family and had already been to mission schools within the Cherokee Nation before he came to Cornwall in 1818. His romance with Sarah Northrup would have been utterly conventional had he not been Cherokee and she not been white. He was sick and entered the Northrup home. Sarah and her mother nursed him. He fell in love with Sarah and she with him.

The family sought to disrupt the romance by sending Sarah to her grandparents. The American Board decided it was time for John to return home, but neither distance nor time stilled their passion for each other—a passion that disturbed the social order. John Ridge published a denunciation of racial prejudice that allowed the “most stupid and illiterate white man” to disdain the most polished Indian. With Sarah’s devotion to John remaining strong, and her parents fearful that she would waste away longing for him and become vulnerable to consumption, Sarah’s family agreed to the marriage. It took place in January 1824, after John returned to Cornwall. Although some defended the marriage, much of Cornwall was outraged, and threats of violence accompanied the denunciations. John and Sarah moved to New Echota in the Cherokee Nation.

The marriage of John Ridge’s cousin Elias Boudinot to Harriet Gold bred even greater resentment and brought public demonstrations of disapproval. Harriet’s brothers and sisters and their spouses bitterly opposed the marriage. One of her brothers-in-law, the Reverend Cornelius Everest, wrote, “We weep; we sigh; our feelings are indescribable. Ah, it all is to be summed up in this—our sister loves an Indian! Shame on such love.” A minister from a neighboring town married Elias and Harriet in March of 1826 because the local minister refused to do so. They, too, would depart for the Cherokee Nation.

The school defended racial equality in the abstract, but not the actual fact of the marriages. Its evangelical supporters would not accept intermarriage, and the Ridge-Northrup wedding appears to have precipitated a decline in contributions. The founders had lost faith in their scholars, the last of whom would leave in 1828. Most of the graduates were disappointments to their teachers.

• • •

With the Boudinot-Gold marriage, Demos’s attention shifts to Cherokee country, and he signals the shift with what he calls an interlude. Demos narrates his own journeys paralleling those of his characters. He traveled to Hawaii to find Obookiah’s birthplace. And nearly two centuries after the Ridges and Boudinots settled in New Echota, Demos went for a visit.

We cannot time travel. A stop in Cornwall, or New Echota, or Obookiah’s birthplace leaves the visitor firmly in the present. But the past often lingers; its evidence endures. There are original buildings in Cornwall, fewer in New Echota. And at these sites stories and storytellers meet. Right here, in this house, this happened; here, these people once lived.

The historian’s next step is at once problematic and wondrous. Demos takes it. “In my mind’s eye I can glimpse the scholars passing in and out,” he writes of his visit to Cornwall. Being there “lessened the distance between my own world and that of the school.” Similarly in Georgia he muses that, for Harriet Gold, New Echota was a blank space to be filled in by experience. “So too, in my own case: an equally blank space. Until I have a chance to go there.” He travels to encounter traces of the past that remain visible.

That past was a Cherokee past, and what happened to the Cherokees in the 1820s and 1830s was a disgrace to the United States, but it was not a simple story, and Demos does not try to suggest otherwise. The Cherokee story shadowed, he writes, “on a vastly grander scale, that of the Foreign Mission School—high hopes, valiant efforts, leading to eventual tragic defeat.”

The same sense of mission and providential destiny that created the mission school ultimately did in the Cherokees. This is not to say the American Board destroyed them; many of their missionaries remained ardent supporters of the Cherokees’ attempt to retain their homeland. But the very sense of Christian superiority and providential favor for the United States embedded in the school also inspired those who sought to dispossess the Cherokees. Indians recognized this, and tried to counter it. They sought to separate American providential thinking into its secular and religious strains and pit them against each other. Indians hoped Christians would not evict Christians. They would, and they did.

Both Ridge and Boudinot had reason to doubt the value of the American Board as an ally, and neither thought that the United States would honor existing treaties. Seeing resistance as hopeless, they joined the Treaty Party, which ceded the Cherokees’ homeland to the United States. The Treaty Party had no authority, and the vast majority of Cherokees who followed Head Chief John Ross opposed them and their treaty, which was ratified, if only barely, by the Senate. In what Demos rightly describes as ethnic cleansing, the Cherokees and their neighbors lost their land, and many lost their lives in government roundups and a forced march west. For enabling this dispossession and dislocation, Ridge and Boudinot would pay with their lives when the surviving Cherokees reached Indian Territory.

The removal of the Cherokees would seem to make the tale of the Heathen School a familiar American story in which race takes the center stage. Racial prejudice sought to thwart the marriages of the Ridges and Boudinots and ultimately did in the school itself. Racial prejudice launched the Cherokees on the Trail of Tears. But if race in the United States is a familiar topic, it is also a complicated one, and Demos shows its complications. His great strength as a historian is his ability to move effortlessly from the personal to the national, and when he does so here, a story about heathens and “colored boys” expands to include black slaves.

Many members of the Cherokee elite were slaveholders, and when Sarah Ridge, née Northrup, moved to Georgia, she mutated from a Yankee to a plantation mistress. She was in the eyes of both Cherokees and black slaves a “white lady,” the very status that brought so much trouble in Cornwall. With her husband’s assassination, Sarah was described as having “a dead heart in a living bosom.” Her Cherokee relatives sought to strip her and her children of their inheritance since she was “a white lady and had no clan.” She lived by hiring out her slaves. Her sons grew up quarrelsome and violent. They, along with a sizeable number of anti-Ross Cherokees, stood with the Confederacy, as did, although Demos does not mention it, Boudinot’s son, Elias Cornelius.

Lyman Beecher’s descendants became abolitionists, but the descendants of the leading Cherokee graduates of the Heathen School joined the Confederacy in defense of human slavery. Two of them, John Rollins Ridge and Elias Cornelius Boudinot, eventually fled the Cherokee Nation under threat of death and ended up alienated from both their New England and Cherokee roots. The failures of the Heathen School had only ramified.

Demos draws a parallel between Cornwall’s opposition to interracial marriage in the nineteenth century and the illegality of same-sex marriage in the twenty-first. His intent, I think, is something more than to compare inequities, particularly since, with same-sex marriage now legal in Connecticut, the analogy might produce comforting feelings of growing tolerance. Demos is too good a historian to think the past will be much of a comfort to us. He has crafted the book otherwise. His heroes, Sara and John Ridge, do not become villains, but they are more than simply victims of racism. Similarly the Cherokees and Hawaiians were betrayed and despoiled, but they were not innocents.

Demos’s analogies have a deeper target: the American sense of being a beacon to the world, its last best hope. This only leads us astray. We want to shape the world without the world touching us and revealing our own limits and prejudices, but more than that we insist on foreigners being unrealized versions of ourselves. We educate the Sisis and Morsis thinking they will become agents of our desires and in so doing forget that they, like the students at the Heathen School, were never ours to shape.