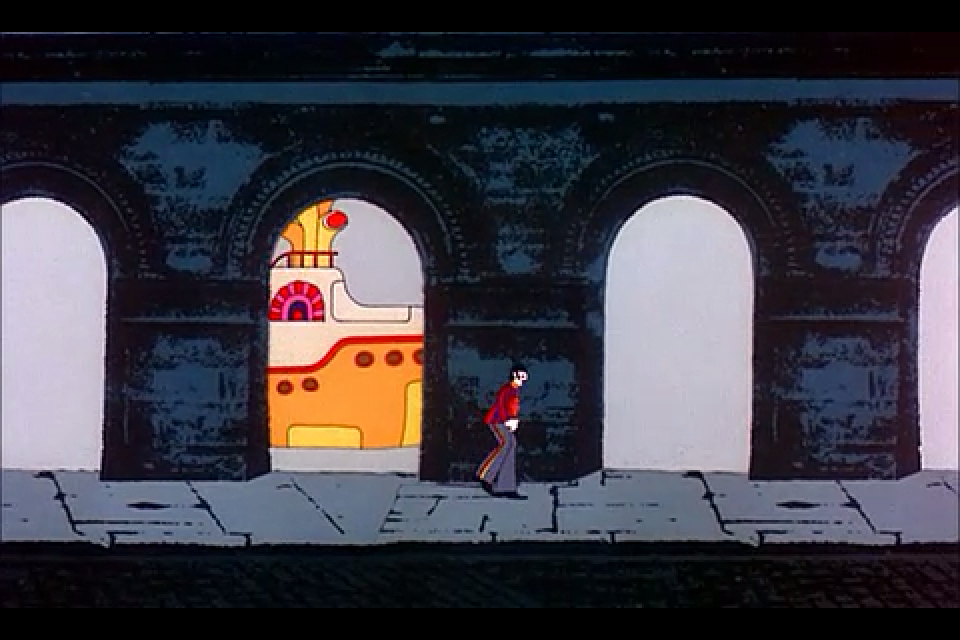

The final scene of the 1968 animated Beatles movie, Yellow Submarine, shows the character of Jeremy Hillary Boob, Ph.D., pirouetting through the cosmos, borne by a constantly expanding flower. He is the nerd-hero; he has triumphed over the closed-minded, music-hating threat of the Blue Meanies, proving that even the cruelest of adversaries can be transformed by the power of beauty, love, and a classical education. Yet when we first meet him, Jeremy is pitiable, a “Nowhere Man”: a bulbously shaped, furry, pink-tailed creature who alone remains in the void when a Vacuum Monster sucks the world into his snout and then devours himself. He babbles in Latin about his articles, his essay for The New Statesman, his educational pedigree, and his yet-unfinished novel. Everything he has written is “for nobody,” the Beatles observe.

Jeremy is a satirical representation of Jeremy DuQuesnay Adams (1934–2016), medieval historian at Yale and Southern Methodist University, a professor fondly remembered for his resonant voice, wide smile, wild suspenders, and entertaining ties. At Yale his books won prizes, but in those days a single no vote could void a tenure case, and Jeremy was the victim of jealousy or resentment or skepticism of some kind. In his later life, exiled in Dallas, Jeremy found generating books cumbersome. In the classroom, however, he still stood out for the quality of his engagement with students: a mind vividly alive, capable of tacking between ancient philosophy, art history, theology, debates about charter schools, and contemporary theories of child development.

The university has always played a role in humanizing public discourse in an increasingly pluralistic society.

Jeremy found his way aboard the Yellow Submarine at a time when the public role of the university was changing. The real-life Jeremy’s college friend, Erich Segal, also denied tenure at Yale, had been invited by United Artists to thoroughly revise the Yellow Submarine screenplay before its production, writing in a version of his old friend. Like many of his generation, Segal believed that the university in general and the humanities in particular could help to humanize public discourse in an increasingly pluralistic society. From Love Story (1970) to The Class (1985), Segal’s novels struggle with themes of pluralism and universal virtue.

Jeremy also found himself treating ancient themes in an inclusive new light. Before I audited his seminar on St. Augustine at age seventeen, simple binaries divided my world into atheist liberals and Christian conservatives. I vividly remember Jeremy’s classroom presentation of the reevaluation of women’s worth in the classical world. In ancient Rome, the story of Lucretia offered a cautionary fable. The virtuous wife of a politician, Lucretia was raped at the point of a sword by a despot’s son, and afterward took her own life. Her suicide was vaunted by the classical poets as the model of female dedication to family honor. Augustine had argued, against his pagan counterparts, that Lucretia’s suicide was in fact a cardinal sin, surrendering to despair instead of trusting in the divine. In this way, Jeremy explained, early Christians staked their belief in the value of women’s souls to their creator, and by implication, pressed against a culture that blamed the victims of rape for their own misfortune.

To present these arguments in a Dallas classroom in the 1990s was unavoidably political, implying a comparison between the sexual equality of the early church and the sexual inequality of the present day. The public schools, despite their liberal teaching of evolution and global warming, boasted few sex-ed classes, and those that were available offered only vague explanations, mostly harping on the evils of premarital intercourse. Victim-blaming often accompanied any mention of rape.

Encouraged by the erudite tradition of medieval biblical scholarship, the students who heard Jeremy’s lectures were able to crack the door of enlightenment a little wider, glimpsing how a reader might take a radical position within the church, or (in this case) how Christians and Texans might become feminists without losing their identity. In Dallas, insofar as church politics mattered, church history mattered as well. History challenged Dallas’s prejudices about gender in its own language, juxtaposing the conservative politics of Dallas with the reality that identities and institutions change—an idea which suggested that change might come in our own time as well.

Mentorship is how the humanities justify themselves: by sharing knowledge of the past with others so that through these relationships, they too can become both tender and wise.

Jeremy spent much of his professional life navigating a culture that was less confident than he about the continuing relevance of classical learning. In 1968, the year of Yellow Submarine’s release, students across America were rebelling against requirements to learn Latin and attend chapel services. Throughout the film, the Beatles spout anti-intellectual witticisms (“Fudd,” reads Ringo flatly as he pronounces the “Ph.D.” on Jeremy’s card). John quips distorted Einstein and Vedic philosophy. To a generation already skeptical of the university, the Beatles represented proof that creativity and love were to be found in popular culture, not in the classical canon. What use had the Beatles, or their fans, for footnotes or dead languages? For his part, the real Jeremy never suffered from skepticism about the canon. He continued to insist on the Western canon’s power to transform the life of anyone who appeared in his classroom, mine included.

• • •

When I met Jeremy, I was a high school student, presuming upon the auditing system to attend his seminar. He befriended me, invited me to tea, coaxed sincere opinions about Plato out of me, and talked to me about my future. I was not the only one. At his dinner table I met dozens of alumni of all genders, ages, and backgrounds who had been drawn out with the same tenderness.

In exile, Jeremy refined the virtue of mentorship into a spiritual discipline. How many of us who teach at Ivy League schools, or even at a liberal arts college such as SMU, would make room today for a high school student—an auditor, no less—at the seminar table, let alone invite her to tea? We favor the students we can groom into research assistants, the ones we can send to graduate school to prove that our work is still relevant. I see these instrumental tendencies in myself, and remember how much I benefitted from Jeremy’s mentorship, which looked for none of those rewards from me. Mentorship, for him, was ultimately how the humanities justify themselves: by sharing the knowledge of the past with others so that through these human relationships, other people too can become both tender and wise.

Jeremy’s lively thinking left ideas still working in my mind decades later. He introduced me to the insight that histories of landscape had been highly theorized in the 1970s and ’80s and were due for a serious return in cultural history. That thought kept me working on landscape theory, a subject then out of vogue at Berkeley, weaving it into my first book and a series of articles and online essays. He also posed to me the question of what had become of Fernand Braudel’s longue durée approach to history, and insinuated that medievalists might have had a different place in the life of the mind had more modernists worked on longer timescales. Those questions fed the conversations with David Armitage that became The History Manifesto (2014), our own contribution to longue-durée thought.

Turning down an Ivy League job when I was well along the path to tenure, I returned to teach at an institution that engages and challenges the conservative South in their own language.

However much Jeremy may have grieved his expulsion from East Coast intelligentsia, I think of him as a paragon of intellectual life. At Harvard, I visited the student literary societies—the Signet and the Advocate—and left convinced (perhaps unfairly) that my contemporaries’ love of learning paled in comparison to that of the “interested and interesting,” as Jeremy described his own generation. For my part, I wanted a life like the one that Jeremy had made for himself. I had inhaled the dream of the humanities’ relevance to the present; the perspective of ancient wisdom on current struggles over identity or church or state; the charismatic lecture or personal seminar as the ideal crucible for shaping engaged, passionate citizens.

Jeremy set me on my quest to talk to business majors, Republicans, and the southern establishment by writing accessibly about state and market and virtue and democratic participation in the past. This fall, I am bringing that dream into reality, teaching in the SMU history department where Jeremy taught. When I accepted the position to join his department, I made a choice that would be shocking to some, turning down an Ivy League job that I didn’t have to leave and where I was well along the path to tenure. I returned to an institution that seeks to engage and challenge the conservative elements of the South in their own language. I returned home to revive a relationship with the people of the region where my parents and siblings still live. What I had seen Jeremy do under coercion, I knew that I could do by choice. I left a dream job for a life that was a dream, and that has been mentorship’s longest gift.

At SMU today, historians are challenging the Texas curriculum and bringing greater attention to the history of racial violence in the southwest. They understand how historical studies can transform the minds of American college students whose politics derive from affluence, fear, and often a degree of ignorance. As Jeremy knew, even students dedicated to conservative values and the ethics of business can recognize the value of history. To talk to those students about change is very much why I wanted to earn a doctorate in history. Long before I began college, I understood that studying the past presents the opportunity to reform the world a little on behalf of the future.

Until the last scene of Yellow Submarine, it is unclear why the Beatles need an intellectual to accompany them on their world-saving journey across the sea of monsters to Pepperland. Despite their skepticism, their Latin-spouting friend saves the day. With Jeremy’s touch, roses sprout from the noses of the villains. Assaulted by his erudition, their hearts open and the war ends. Yellow Submarine offers an allegory on the value of the humanities in a populist age. Popular culture can enkindle the heart and bring beauty into the world, but some knowledge of our common past is necessary to change the minds of one’s purported enemies.