“Today, we’re hermit crabs,” Maryanne tells me, and so we are.

We change homes. We’re opportunists, omnivores. We’re not picky. We eat with our mouthparts. We molt. “When my hermit crab Shelby died,” my wife says, “Mom told me its soul had migrated to a better home—she said better home. Within a week, she divorced Dad. Years later, I found the signed papers in a file box. Her handwriting was sloppy. I could only make out the phrase nutritionist’s feet. I still think about that sometimes. Where that better home is.”

“Maybe my dead dick migrated to the same place as Shelby?” I say, and knock on it.

There was a marriage once. A white status quo. Tin cans chasing the car bumper all the way home. The key worked then, the door unlocked. I carried Maryanne across the threshold. We were young.

“It’s just hibernating, David,” she says, and laughs. She kisses my cheek. Her lips are chapped. We could bite off each other’s fingers, a decade of devouring love. I itch, I sweat, I crawl out of my skin with it. We’ve made homes inside each other. The property tax is cheaper here anyhow. Then Maryanne vomits, suddenly very sick again.

So I push her in our shopping cart along the tracks in the gulch to see the doctor.

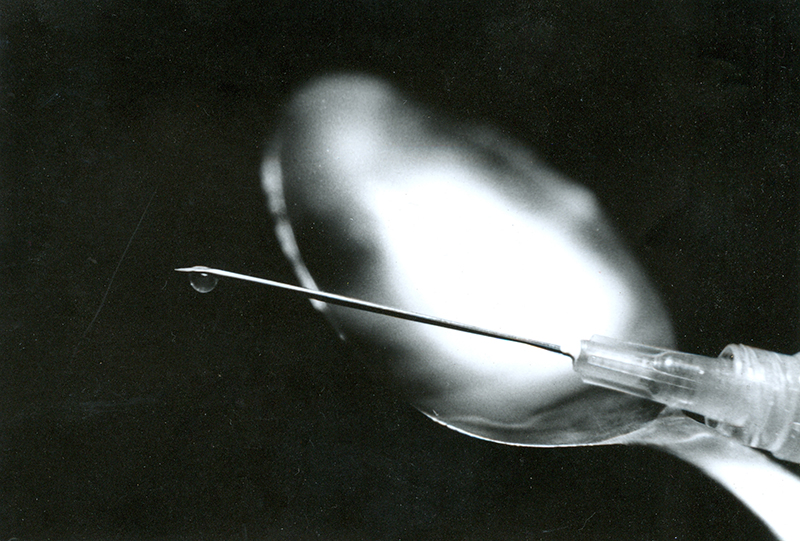

“Please,” I tell him. “She needs to get well. I can’t. I’m too squeamish.” I hand him a hypodermic. The doctor holds it up to the light between the gap of wet plywood and tarp and flicks it. It’s freezing in the doctor’s office, it’s freezing in the sun. I look away and hold my breath as he plunges the needle into Maryanne’s side-throat.

Maryanne’s eyelids hang. Her sweat recedes into her spongey parts. She crouches and twists like a living algebra equation. She molts. Her happiness haunts me. I vomit a vision of a church, her in a white status quo. I offer the doctor a second needle. “I need to get well, too,” I say. “Don’t shoot until you see the whites of my eyes.”

But he does stop. I feel the not-feeling of its second happy half before my eyes roll back.

“What’s this?” I say.

“My co-pay,” he says, and feeds the needle between his toe flesh. “This ain’t Canada.”

“You’re a fair doctor,” I say. “Thank you.”

It’s a warm salt water orgasm. We half-migrate to better homes. Maryanne’s thinking about anything but the pain in her teeth. Nothing will steal her joy again.

“Where you from?” the doctor asks.

The three of us heap among the bottles and cushions and treadless tires. A shirtless man on the opposite gulch slope has a silent nightmare on a box spring.

“Not far,” I say. “We’re on sabbatical. My wife and I work at the big college.” A train clunks past in a slow blur. I’m cold, I cuddle Maryanne. So does the doctor. He examines my wife’s breasts under her shirt as she sleeps. Then he examines me, but my dick is dead and he quits, or he just nods off.

In the night, Maryanne nudges me awake. “Make yourself smaller, David,” she says. We are sharing a too-small towel lying on a couple of pallets under the gulch bridge, and it’s raining. The doctor is gone. “Hermit crabs make themselves smaller to fit their homes,” she says. “You’ve got to make yourself smaller so we can both fit. Don’t you love me, David? Always and forever? Do you want to marry me all over again?”

I do, I tell her.

• • •

We fill our shopping cart with wire and pipe fittings, a toaster and hair dryer and razor blades from dumpsters in front of gutted homes. “During World War II,” I say, “compasses were smuggled into German war camps made of these razors.”

“This is why you got fired,” Maryanne says. “You’re filled with useless history.”

“I make history fun,” I say. “And I didn’t get fired. I’m on sabbatical.”

She’s sizing up a mood, which means her teeth must be starting to bother her again.

Martín appears, pulling a wagon of scrap. Gualtieri appears, wearing a bag of golf clubs.

“Are those Callaway Hybrids?” I say. “You scored those from one of these houses?”

“I scored these from a house,” Gualtieri says. His bad, limp left arm is covered in scabbed constellations. “This block is going to be one big fucking blue light special,” he says. “We got to eat while it’s hot. Let’s set up shop and scrap like gentlemen.”

“Gentlemen?” Maryanne says.

“You know: work smarter, not harder,” Gualtieri says.

“But I’m a woman,” Maryanne says.

‘You still grind your teeth,’ I say. ‘I wish you had those pills to help. Remember those?’ ‘Ahhh,’ we say, and remember.

Martín is staring at a disemboweled house with tears in his eyes. “This one was mine,” he says. Martín is maybe eighteen. “I came home and the locks were different. The city posted a notice on the door. They were all gone,” he says. “My guess is if they had a choice they went anywhere but back to Guanajuato.”

“The banks did the same thing to us,” Maryanne says. “Changed the locks on us.”

“I’m sorry about all this,” I say.

“All what?” Martín says.

“This,” I say, waving my hands around. “The times, everybody trying to kick you out.”

“Look, man,” Martín says. “My race is my problem. Don’t try to take that away, too.”

“But this is the land of opportunity!” Maryanne says. “We have inalienable rights!”

“But I’m an alien,” Martín says.

“Don’t feel sorry for him,” Gualtieri says. “This is the fifth house he’s said that about.” He takes a break from the scrapping and leans against a yellowed tub, his shirt soaked through. He wipes his brow and gasps, looking like wet gray steak meat.

“Gualtieri,” Maryanne says. “Don’t let me out-gentleman you.”

I laugh. Gualtieri grimaces.

Then the property owner rolls up in his truck. “Are those my golf clubs?” he says.

Gualtieri unsheathes the seven iron with his good right arm and swings it through one of the headlights. “I served my country for you! Then I tore my rotator cuff for you specifically, you bald bitch! You are free to offer that shit insurance with that shit network because of me!” He slams the iron down onto the truck’s hood.

When the owner steps out, he’s carrying a pistol.

We run.

“Scavengers!” the owner yells.

“Opportunists!” Maryanne yells, correcting him over her shoulder.

• • •

We get a buck for the ten pounds of scrap metal, plus five more for the copper wire.

The toaster and hair dryer are worth zilch to the salvage yard.

“They’ve got shiny parts,” I say. “Mirrors are a commodity.” So we keep them. Tin caterpillars scream along the El and disappear behind a billboard for a strip club. Maryanne grabs my dick.

“Still dead,” she says.

“If this were Renaissance France, you could take me to court for it,” I say.

“It’s not me, is it?” she says.

“Of course not,” I say. “I love you.”

“You can love me and still not think much of me,” she says, and looks at her sandals.

“I think very much of you,” I say. “I always told the sommelier to let you smell the cork.”

“But it wasn’t always dead,” she says, and rubs her scratched jaw. “Your dick, I mean.”

“No,” I say, and rake my arms and legs. “It wasn’t.”

“What changed?” she asks, shaking out her hair.

“Nothing,” I say, and rub my chest. It’s tender and tight, like I sprained my heart.

• • •

The Victorians honored the dead by posing them for portraits. Photographers used long exposures, and the edges of those breathing or fidgeting would blur, leaving just one person so clear and sharp you’d swear the camera somehow chose her.

If the pay phone at Front and Lehigh rings, and we’re not there to hear it, does it ring?

Sometimes when we’re there it does ring. I answer it, “Hello?”

“You’re killing your dead mother deader,” my dead father says.

“I’m going to kill you when I find you,” Maryanne’s father says.

“You’ve found me,” I say. “Us.”

“I know,” he says. “I’m around the corner. I can’t bear to look at what’s become of her.”

“I can,” I say, and look at Maryanne, who’s nodding off. “I’m looking at her right now.”

“You bastard,” he says. “You ass.”

“Was that a shot at us?” my dead father says. “That was definitely a goddamn shot at us.”

“What’s happening, Ed?” my deader mother says in the background. “Who took a shot?”

“The General believes we conceived our son through the rear end,” my dead father says.

“I never liked him,” my mother says. “He didn’t even walk his daughter down the aisle.”

“You don’t really give a damn,” I say. “You didn’t even walk Maryanne down the aisle.”

“I really do,” the General says. “And she’s perfectly capable of walking herself. Or was.”

“Was that a shot at me?” I say. “I’m her husband. It’s my job to take care of her.”

“I raised Maryanne to take care of herself. Character isn’t forged from handouts.”

“We’re fine, sir.”

“Fine, you say? This place makes Kuwait look like the fucking Sarasota Benihanas.”

“We have inalienable rights to pursue,” I say. “Happiness.”

He snorts, the timbre of high cholesterol. “My fucking men died for your happiness.”

“History is cyclical,” I say. “Soon enough, you’ll be dead, too.”

“Well, save me a seat. At which point I’ll gladly kill you deader.” And he hangs up.

“Well, I hope you live a long life,” my dead father says. “But once you die of natural causes, many years from now, under different circumstances than these, I hope the General kills you deader so you understand what you’ve done to your mother.”

“It was the MTV,” my deader mother says. “Tell David I blame myself for his choices.”

“Who’re you talking to?” Maryanne says, coming back from her nod.

“You’ve got the wrong number,” I say, and hang up.

• • •

The street smells like semen from the white blossoms on the pear tree above us where a pair of Converse dangle by their tied laces. We feel like inside-out vampires. We have dinner forks in our eyes. We feel like brittle Styrofoam. Our thermometers are broken. The wolves howl into our sticky red parts: little pig, little pig, let me come in.

“They missed a wisdom tooth,” Maryanne cries. “I feel it in my jaw. I feel impacted.”

Suddenly, I am very sick.

I look away when she gives me my half, herself hers. We marry each other again.

When Stevie Baluster appears, whistling, I’m Jesused across Maryanne’s femurs, and she’s got her hand halfway down her throat. We pay the piper. She unknots the yellow balloon skin with the red smiley face. She loads the spoon. She loads a new needle. She fashions me a tourniquet with the laces of the Converse. Then she loads me.

“Put those shoes back,” Stevie says.

“Asap,” Maryanne says, then shoots her happy half.

We circulate and sigh, gilded. The steel wool in our veins disintegrates. Stevie Baluster disappears, and Maryanne lays her head on my chest. I wonder if she can hear the true lie of my heart—that this voyage is sex with one thousand teenage Maryannes.

“Did I ejaculate?” I say. “It smells like I ejaculated.”

“We’re both ejaculating,” she says, and rearranges all of her face parts into glory.

• • •

A naked man swivels in a wheelless office chair at the corner of Tusculum and B. The street glitters with galaxies of green bottle glass. His frostbit black parts look like his insides spilling out. “I’m from Northern Cali and I brought the wildfires with me!” the man shouts. He spins and tips into the street glass. “Cool shoes,” he says to me, bleeding.

We follow a trail of his bloody footprints into a maze of vacant houses, into one filled with laundry and mattresses and a couple hundred more bottles and cans. We recycle them for ten bucks. We buy chips and root beers at the dollar store. Then we find a mattress in another empty house. We wait for the sun. We are ravenous.

“We make better homes,” Maryanne says.

“We do,” I say. “And with no lawn. God, I hated mowing under the picnic table.”

‘Today, we are jellyfish,’ Maryanne says, and so we are. We drift on the whims of our nerve nets. We glow in the dark.

“We wrote our dissertations at that picnic table,” she says. “Graded, researched.”

“Burned the citronella at both ends,” I say.

A hole in the plywood over the window offers a view of a UHaul lot where we can hear a colony of feral cats raping the afterlife out of each other.

“I ground my teeth in my sleep over that dissertation,” she says.

“You still grind your teeth,” I say. “I wish you had those pills to help. Remember those?”

“Ahhhhhhhhhh,” we say, and remember.

• • •

“Today, we are jellyfish,” Maryanne says, and so we are.

We drift on the whims of our nerve nets. We glow in the dark. We are shaped like trash bags. We regenerate if cut in half. We travel backward to the polyp stage, degenerate in times of stress. We are pink meanies. Our special cells are filled with poison.

We return to the pear tree—or a pear tree. No Converse hang from this tree.

“Why don’t you just get a map already?” Maryanne says. Her teeth must be bothering her again.

“I don’t need a map,” I say, and point in four directions. “Never-Eat-Shredded-Wheat.”

“Someone’s coming,” Maryanne says.

“It’s just the smell of that tree,” I say.

“No,” she says, and points at the gaggle of tweens on bikes. They pop wheelies around us, throwing chin music with their tires. Stevie Baluster pulls up on his red Huffy with a squinty black eye and a baseball card throttling in his spokes.

“Where are the Converse?” I say.

“Are you serious?” Stevie says, and points at my feet.

“When did that happen?” Maryanne asks me.

A tween with a temporary skull tattoo on his neck says, “Let’s practice on her.”

“Just take your shoes back,” I say when Stevie flips open a switchblade.

“Those aren’t my shoes,” Stevie says. “I paid the piper for you, you thief.”

“You’re not the piper?” I say.

“My older brother,” he says.

‘Help!’ I say. But they’ve heard this story. They don’t realize how slippery the world is, how we’re all sliding off it.

The tweens get off their bikes. Maryanne steps behind me. “David,” she says.

I put the shopping cart between us and Stevie. I see the hair dryer and grab it.

Stevie laughs, “What’re you going to do with that, you dirty junky fuck?”

I swing it around like a lasso, in figure eights like nunchucks. I’m all cowboy, all ninja. “The shortest war ever was the Anglo-Zanzibar War of 1896. It lasted thirty-eight minutes. I’m about to break that record over your tween asses—”

Suddenly, I’m very sick again.

And in this moment the hair dryer swings back and cracks into my nose.

I watch a star explode, the birth of a new universe.

• • •

The church I wake in isn’t like the one we did not attend. Except the once. There was a marriage once. A white status quo. Tin cans chasing the car bumper all the way home. The key worked then, the door unlocked. I carried Maryanne across the threshold. We were young. We ordered Nigerian takeout. Maryanne said an aphrodisiac spice would activate my mitochondria and sperm motility. I noted the Egyptians believed semen came from a divinely-blessed vertebrae, and a bad back could cause impotency. We tried for a family. But we are scholars of liberal arts and sciences. I went to a chiropractor and Maryanne ate junk food until her teeth rotted.

“The trick to Baked Alaska,” a woman says, holding a lighter beneath a mints tin, “is to leverage the insulating properties of the meringue. That’s a fine tattoo.” An older man with a monkey inked across his chest sits on a damp sleeping bag under a statue tagged with many hundreds of signatures.

“Got it in Saigon,” he says. “My local girlfriend there told me I was born in the year of the monkey. She said I was born with an untamed nature. She was right. I burned her village to the ground. I jump-started their ecosystem in the year of the tiger.”

“We were born in eighty-two,” Maryanne says, appearing beside me. “What year is that?”

He counts on his fingers. “Year of the dog.”

“And me?” Baked Alaska says. “Seventy-one?”

“Year of the pig,” he says. Then he laughs. It echoes around the neighborhoods inside us.

“What’s so funny?” Baked Alaska says.

“Monkeys and dogs and pigs,” Saigon says. “We’re lab rats.” He sticks a needle into the monkey tat and gnarls both of their bodies. Yellow rivulets trickle out of his jean cuffs. Baked Alaska uses her reflection in the toaster to find a neck vein, then drapes herself across a pew.

“Dr. Benjamin Rush,” I say. “believed man is feral, whose happiness requires wildness.”

“Then if we are dogs, today we are coyotes,” Maryanne says. “Also, woman is feral, too. Let’s not bring gender into it.” We chase the roadrunner. We lick our wounds. She licks her cut lip. My snout is bent funny and I can’t breathe from one nostril. Suddenly, I am very sick, and Maryanne is very sick. The sweat makes her forehead look like it’s boiling. She wraps a cord around my bicep until my heart beats in my fat hand.

I am very sick, and Maryanne is very sick. The sweat makes her forehead look like it’s boiling. She wraps a cord around my bicep until my heart beats in my fat hand.

“Where’d you get that?” I say of her syringe.

“I traded it for the cart,” she says. “Did you know this is named after a heroic female?”

“From the German heroisch,” I say. “I told you that. And don’t bring gender into it.” I look away when she gives me my half, herself hers. We marry each other again. We dream with our eyes open. Maryanne calls this state the amnion. We are in utero. However, we are suddenly breeched. We take shorter breaths. Saigon vomits and the monkey dances. Baked Alaska turns blue. “Maryanne,” I say, rusty snot in my one good nostril, “what is this?”

Maryanne looks confused, the shade of early twilight.

“I don’t feel so good, David,” she says and tips over.

• • •

A mallet swings into my gong-shaped heart and my blood rattles its chains.

“Good morning,” a nurse says.

“We have an inability to say no to lemon poppy seed muffins is all,” I say.

“Well,” the nurse says. “There’s a strain of lemon poppy seed muffin going around cut with fentanyl. Nineteen of you were in that church. Three of you survived. You both nearly died.”

I look at Maryanne pale and sleeping in the bed beside me, her lip stitched.

“She more nearly than you,” the nurse says. “You had less in your system.”

‘Give her the pills, please,’ I say. ‘It’s her teeth.’ ‘It’s not,’ the nurse says.

Looking at Maryanne, I feel like the sharpness of my body is blunting until everything else feels sharp against it. The mattress feels sharper, the light looks sharper, the nurse’s voice and the beeping machines sound sharper, the scent of cleaner and coffee smell sharper, but Maryanne is sharpest of all. The Victorians honored the dead by posing them for portraits. Photographers used long exposures in group pictures, and the edges of those breathing or fidgeting would blur, leaving just one person so clear and sharp and perfectly still you’d swear the camera somehow chose her.

“Weren’t we in this room?” Maryanne asks, waking, touching her lip. “For stitches?”

“All these rooms look the same,” I say. “You came here for your wisdom teeth, too.”

Maryanne starts to cry. “I feel so sick,” she says. “Why am I so sick all the time?”

“Give her the pills, please,” I say. “It’s her teeth.”

“It’s not,” the nurse says.

“We need to get well,” Maryanne says.

“I agree,” I say. The bed sheets really itch. I think I’m allergic to the detergent.

“You’ve been prioritized,” the nurse says.

“Prioritized?” I say.

“For housing,” the nurse says.

“We have a house,” Maryanne says. “We just need new keys.”

“The locks got changed on us,” I say. “Big misunderstanding.”

“You’d have to be serious about it, though,” the nurse says. “Staying, I mean.”

“Stay?” Maryanne says. She pulls the clip off her finger, and her machine stops beeping.

“We have to go,” I say.

“Of course you do,” the nurse says, and walks out.

• • •

We jump the turnstiles and ride the El out to where there’s grass, where potholes are filled and mailboxes look like movie props, where shopping carts are a dime a dozen and grocery dumpsters are full of expired jerky and fresh fruit with indiscernible flaws. “What’s wrong with this?” I say, and hold up a grapefruit.

Maryanne rubs her jaw and shovels her brow, and says, “We need to get well soon, David.”

“I’m working on it,” I say. “Bingo—six cases of expired seltzer.”

We crack open the 144 cans and dump them. They drain into the sewer in an effervescent river. Maryanne searches for more cans while I recycle the others in the store for $7.20. A grocery worker appears.

‘You tell me,’ I say. ‘How do you just stand by and watch the person you love suffer?’

“Is there a problem here?” he asks.

“No,” I say. “I’m only recycling cans.”

“No, you’re not.” He gives me a look like the one I give students who’ve plagiarized.

“You tell me,” I say. “How do you just stand by and watch the person you love suffer?”

“I suppose you don’t,” he says. “But if you don’t get out, I’m calling the fucking cops.”

Maryanne isn’t at the grocery dumpsters. I find her at the bus stop.

“A worker chased me,” she says.

“Me, too,” I say.

“I forgot the shopping cart,” she says. “I’m sorry. I’m so stupid.”

“You’re not,” I say. “You’re perfect, darling. Remember how you won the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize? How you theorized that vaccines could be strengthened by procuring dead virus that had previously undergone antemortem—how did you put it?”

“Molecular Fitness,” she says, “to thicken the protein coat.”

“How could a stupid person do that?”

The bus stop shelter has a blue light. It’s day, it’s off. In the Plexiglas, I can barely see her reflection, clutching her stomach. She looks scolded. I can barely see my reflection beside her, my swollen raccoon eyes and broken nose. But I can see my veins. I can see the ones that I can’t see. I know them by feel. They all lead to one centralized station filled with blood, a three-dimensional bruise. I call it Maryanne.

“I’m the stupid one, Maryanne,” I say. “I’m so stupid.”

“David,” she says.

And suddenly, Maryanne is very sick again.

• • •

Martín and Gualtieri are shuddering under the El stop. I give them the recycled can money and we pull Maryanne in Martín’s red wagon to the boarded-up church, then pry plywood from a window with Gualtieri’s seven iron. Inside, we find sixteen chalk outlines, needles in the collection plate, and our shopping cart with the hair dryer. I put Maryanne in the cart and push her along the Amtrak tracks in the gulch to see the doctor.

“Please,” I tell him. “She needs to get well. I can’t. I’m too squeamish.”

“Give me the rig,” The Doctor says.

“I don’t have one,” I say. “We need.”

“I ain’t in goods,” the doctor says. “I’m in services.”

“I got,” a cowboy says, exiting the doctor’s office. He’s in leather boots and a Stetson.

“We can trade you this cart and hair dryer,” I say.

“I don’t got any hair,” the cowboy says, and lifts his hat to show a smooth head. “I don’t need no shopping cart neither. I got a rental. I’m in town for a conference. I just got homesick for Lubbock is all. Wanted to roll around in that Mexican mud some.”

“We don’t have any cash at this time,” I say.

“Too bad for you, amigo,” the cowboy says.

“I’ll suck your dick,” Maryanne says.

“What?” I say.

“I need to get well, David,” she says.

“No,” I say. “We’re married. I’m your husband.”

“You’re broke,” she says. “And your dick is dead.”

I look at Maryanne the way you look at a word for so long that you wonder if it’s spelled right. Suddenly, gravity tightens at its edges. Suddenly, I smell again. Trash and feet, the man on the box spring still silently nightmaring, covered in bird shit. Maryanne has unbroken my nose. Suddenly, I am very sick in a very different way.

I kick the cowboy in the balls, hero-ish. I see him go down, knock-kneed and sunburned, I see others stumble out of the brush to descend upon him, taking his wallet and keys, boots and hat, as I push Maryanne up out of the gulch.

“Where are we going?” Maryanne says. “You’re broke. I want a divorce. Take me to that living dick so I can suck it.” She white knuckles a fever dream, wide-eyed. “Take me back. I want to go back to where we were.”

“Maryanne, please.”

I think of how the body eats itself and I think: If you’re going to fail again, you better fail fast.

We get to Girard, the crowd at the trolley station, going to or coming from work.

“Help!” I say.

But they’ve heard this story. Of mothers that couldn’t love, gold stars never awarded, wars never fought in, nonexistent children never fed, sabbatical never taken. They don’t realize how slippery the world is, how we’re all sliding off it.

I look at Maryanne’s toes in her sandals, the tips of them blackened with frostbite. I think of how the body eats itself, like she has said before. I think about how Pope Gregory IX declared cats the herald of devil worship and ordered their mass executions across Europe. In the absence of cats, a great plague spread across the continent, a flu-like illness that filled bodies with blackness. Soon, they broke open at the lymph nodes. All that remained was a husk, a carbon copy. It was a great black plague that spread from the rise of the rats.

Maryanne starts chattering and wheezing in her cart, yelling about sucking all the dicks, and I think: If you’re going to fail again, you better fail fast. So, I shove the hair dryer into my waistband and push the cart into the 7-11 across the street.

“This is a stickup,” I say at the register with my shirt over my bandaged nose.

“What?” the clerk says. “What is this stickup you say? What does this mean?”

“Please,” I say.

I reach into my waistband and grip the hair dryer’s handle. The clerk’s brow rises, doing the simple math. He glows like halogen. I can only gunsling the threat of a blowout. But this clerk is certain he’s going to die. And for what? A few hundred dollars? A Diet Coke? Aspirin for tooth pain? But what does this clerk really know about death? Taped to the register is a picture of Jesus swooning, eyes rolled back. If the clerk believes in heaven, he believes in angels. We have come back from the dead. It’s in our medical charts.

Someone has been watching me. The store windows flash red and blue. A cop walks in.

“Thank you,” I say to the camera on the wall behind the clerk.

“I hate you, David,” Maryanne says. “I need to get well. I want to go back to where we were.”

“I know you do,” I say. “I’m working on it.”