1.

I entered the terrain of the Holocaust on a flat stretch of New Jersey highway. As I tuned the radio through miles of static, the fuzz cleared, and out poured the voice of a cello, an unearthly melody rising up out of the silence like a curl of smoke between floorboards. The music was so haunting that I had to pull over onto the shoulder of the road.

It was odd that I had never heard the piece. For the past seven years I had been working on a novel about a broken-down former prodigy cellist, the daughter of a Russian Jewish pianist whose career had been severed by the war, and who had coped with the ache of his phantom limb by sculpting his child into a world-class musician. In the decade since her parents’ accidental death, the narrator has been playing the cello silently, the bridge muffled; as the book opens she finds herself unraveled, stranded abroad with no resources, after the last person who knew of her past dies. The book tells the story of how she emerges from her trauma via an affair with an Italian male prostitute. Its spark was an understanding of a bond between two surface opposites—she sexually and musically shut down, he a compulsive liar and performer—who are each other’s most impossible partner, and only hope.

In one sense I was writing what I knew, as I muddled my way out of a damaging childhood without the life skills to make it as an adult. Between dead-end jobs, evictions, and surgery on Medicaid, I lived in the old Lincoln Center Music Library in Manhattan, where in one dingy booth or another I was making my way through every recording of every piece in the cello repertoire. Often it seemed that little more than the kerchief I tied over my nose separated me from the alcohol-smelling bums with crumbs in their beards who bookended me, swooning to Albinoni. Never any twentieth century for them. Dissonance, one said, shuddering, as if the twentieth century were a horror that only safe, housed people could afford to play with.

The way it worked was, you screwed the slip of paper with your request into a canister that got sent down a little pneumatic tube to the basement, where hundreds of thousands of records were stored. After a while, anonymous hands held an LP up to a camera: if the title-label on the little black-and-white TV in your booth seemed right, you clicked “Yes” and the label began to rotate. Through headphones, the old recording would get its chance to speak. On second hearing, I would try to write. The problem for my narrator was learning to navigate the present equipped only with her father’s survival rules for the past. But the emotional questions—how to shed the lessons of trauma, to have the courage to abandon the once useful self-protections that later do you harm—were not ones I had answers to. As time went on, I traced back over my story again and again, burying more and more panic about how to finish. In the library, I could hardly ever bear to consign an old recording back into oblivion. I had been listening, crawling my way through the collection, for years.

Probably no writer has found a more powerful metaphor for the stasis of trauma than Dante in The Inferno, where being damned means being condemned to perpetually lapse backward, lapse not just in the Christian sense of repeating the offending sin, but also in the psychic, chronological sense of circling back, of doing laps. Though they forever revisit the past, and envision the future, the residents of Hell repeatedly query Dante about what is going on above ground. What better embodiment of trauma than a blindness to the here-and-now? Like Dante’s damned, I went over the wrong choices that had made me—wrong parenting, wrong life decisions, wrong paragraphs and sentences written—and I could clearly envision the reviews slamming the book. But because what I was really writing was not what I knew but what I needed to know, I could not feel my way in the present. I clicked “Yes” again.

2.

In the car, after a faster movement, the announcer on the radio named the piece as Gideon Klein’s Trio for Strings. What followed made me understand why I did not know it. Klein, like many other Czech Jewish musicians of his generation, had been interned in a transit camp I had never heard of, called Theresienstadt, established in the small, walled-in Czech garrison town of Terezín.1

The Germans billed it as the “privileged” camp where “half-Jews,” World War I veterans, and famous actors and musicians were sent. Klein’s music was now being rereleased, along with the work of an entire generation of post-Dvorak composers who had perished in the war. In this one place, narrative and performance had been used by the Nazis to trap and kill Jews, at the same time they had been defiantly used by the prisoners to save their own physical and spiritual lives. The odds weren’t good—of the approximately 144,000 people in Theresienstadt, 88,000 were sent to death camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau, and approximately 33,000 died as a result of conditions in the ghetto—but you had a chance of surviving longer if you could perform. The Council of Jewish Elders often put performers on their lists of Prominenten, people who were protected from the transports. Musicians who throughout the thirties had been prevented from working threw themselves into activity with a zeal many had long since abandoned on the outside. Theresienstadt had four working orchestras; in addition to symphonies and original operas, hundreds of chamber and lieder concerts were performed, and there were two cabarets: a stodgier German one for the older people, and a Czech one for the young admirers of the avant-guard. According to one historian, for most of the war Theresienstadt had the freest cultural life in the occupied Europe.

Like a wake-up from amnesia, a life spread out before me. It was at Theresienstadt that my narrator’s father had survived by playing, there that he had lost the use of his fingers, there that my narrator would return at the end of the novel to burn her rare cello and exorcise her past. Of course, my narrator could not escape her father’s voice in her head, or trust others in the present. She was trapped in her father’s time, when the price of an error was simply too high.

Though the sky was darkening, I did not start the car for a very long time. Writing about the Holocaust, as a non-Jew, seemed a Pandora’s box. I had spent enough time paralyzed by depression; the Holocaust was a black hole from which I was not at all sure my psyche would emerge intact. As for the writing itself, I had never read Elie Wiesel’s pronouncement about Auschwitz—that only those who had lived it in the flesh could transform their experience into knowledge—but it had seeped into my consciousness.2 After exhaustive research about instruments and performing, I had gained confidence when a cellist I was interviewing began describing an experience of performing in words nearly identical to a passage I’d written the previous week. But unlike classical music, with its graying audiences, and its practitioners who were unabashedly grateful for the interest, the Holocaust as material seemed a frightening, guarded territory, a place you did not want to get caught with the wrong past. That night, I dreamed I was trapped between mile-long floor-to-ceiling stacks of old, dusty LPs in the twentieth-century section of the basement. They were recordings of Nazi torture sessions, the shrieks encoded as dissonance. On one of them, buried in a modernist trope, was the passage that would signal how to find my way out.

You have to suspect anyone who isn’t the child of a survivor, going into the Shoah business. Fifteen years ago, the hero of Don Delillo’s White Noise, the founder of the field of Hitler studies, was understood as an absurdist comic construction, a suburban dad who cashed in our lurid obsession with this monumental misery and used it as a ticket to academic upward mobility. Since then the field of Holocaust studies has burgeoned to the degree that it is now a required history course in many high schools, a department in some universities, and a museum on the Washington Mall. It is a cataclysm so large that everyone can project onto it. In addition to the myriad documentaries, museums, monuments, novels, plays, and musicals, the field of “Holocaust Theology” is now offered as the discipline of the profound ontological knowledge-state survivors have access to, based on their experience. Where the Kabbalah stands for the mystery of light, Auschwitz comes to stand for the so-called “mystery of darkness.”

I spent a year trying not to know what I knew about my narrator’s past, to continue building my story in the present. But where the construction was shoddy, more smoke seeped in. Over and over, I tried to plug up the holes, to think up solutions that did not relate to the Holocaust, because the more I thought about it, the worse an idea writing about the Holocaust seemed. I had written a survivor father who, in trying to protect his daughter, profoundly damages her ability to function, and a daughter whose tangled guilt causes the death of someone in her charge. But when you are condemned to write fiction, imaginative truths seep in, and once they do they become embedded. One day you know them, not the way you piece together a dream, but the way you know the place you grew up. In the scene I knew, my narrator was trudging towards Terezín on a self-imposed march, intending to exorcise her past and burn her rare cello in the crematorium. No matter how I tried to write my way around that scene, to find a different ending for the book, I could not come up with it. Finally, I gave in and began to read.

3.

All deadly regimes rewrite history. But what immediately struck me about the National Socialists was their intense engagement not just with annihilating the past, but with fabricating an elaborate false reality. Next to the leaden arguments the Russian, Chinese, or Cambodian revolutionaries came up with, and the brutal chaos that followed, the Nazis’ civil war against the Jews was terrifyingly well scripted. Their sophisticated weaponry included film, law, performance art, elaborate twisted historiography, and a rich palette of Jewish religious symbols, all aspiring not just to power or “equality” but to nation-as-art. As storytellers they were masterful, their tales epic and mythic.

Who would have thought to use postmarks to tell a tale? Even the tiny traces of the Nazis’ annexation of Czechoslovakia reflect the intricate ways they used story to seduce and invade, assimilate and then annihilate. After Hitler took the Sudetenland—the bicultural horseshoe swath of Bohemia and Moravia whose many ethnic Germans Hitler yearned to reunite with the fatherland—the postmarks encapsulate the deadly narrative shifts in miniature: first the bilingual Czech/German postmarks are absorbed into the metonymic “Hitler/Chamberlain” cancel (whose two-day meeting sealed the fate of Czechoslovakia without Czech approval or participation); then the Czech town names disappear, assimilating the towns into the Reich; and then German postmarks begin to state, “We are free!” and “We have thrown off the yoke,” effacing any possibility of another interpretation.

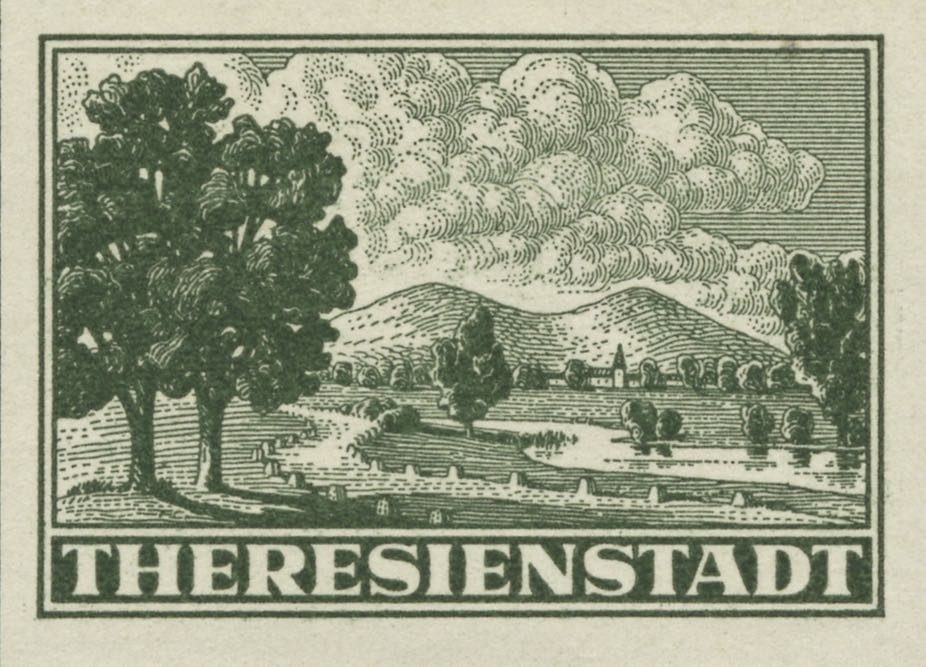

In the case of Theresienstadt, the Nazis published brochures advertising property at a privileged resort town where Jews could resettle, “Theresienbad,” whose name alluded to the famous spas of Karlsbad and Marienbad nearby. (Not a few wealthy families, attempting to secure a place for themselves, handed over their fortunes to buy lake-front villas in this lake-free town, and some arrived at the camp in evening dress.) Prisoners were given specially printed Theresienstadt Monopoly-money for their labor, with which they could “shop” in the stores for the possessions and clothes that had been stripped from them upon entry.3 The Nazis set up a Council of Jewish Elders, ostensibly giving prisoners a role in self-determination. It was here that the film, Der Führer Schenkt den Juden eine Stadt, “The Führer Gives the Jews a City,” was made, with its shots of Jews waving from their gardens on the floor of Terezín’s old moat. Through the lens of history the emaciated prisoners look barely capable of smiling, but had the Nazi narrative prevailed, the same shot might now suggest weathered pioneers determined to make a life under hardscrabble conditions. Even the Theresienstadt admission stamp gave off a masterful lie, depicting an idyllic pastoral scene, a river and road snaking back from lush foreground trees to low hills scrimmed by a huge cumulus cloud.4

What was fascinating for my own tale of two performers was the way the warring performance strategies mutated in response to each other. To tidy the stage for a Red Cross inspection, the Nazis deported the deathly ill patients in the infirmary, and charged other prisoners to lie between the sheets and play the role of patient. To further the “paradise ghetto” fiction, they attempted to co-opt the musical activity by forcing the prisoners to prepare a concert. The prisoners countered by choosing the monumental Verdi Requiem, intended as a requiem for the Reich. Even the report that narrated the mise en scène Hitler hoped to pull off seems to have been a piece of performance art by inspectors who took in the reality, yet colluded with the farce.

“Revisionism is an ancient practice,” Pierre Vidal-Naquet wrote, “but the revisionist crisis occurred in the West only after the turning of the genocide into a spectacle, its transformation into pure language.”5 If rhetoric can precurse genocide, then it makes sense that the title of Vidal-Naquet’s book about revisionists, Assassins of Memory, wrests a physical act of violence onto an abstract object via catachresis, conflating truthtelling with preserving life, and rewriting with killing.6 And it makes sense that there are those who would want to keep storytelling on that subject off-limits to those who might do it wrong. In the wake of the tidal wave of narrative abuse by the Nazis, and the subsequent kitschy exploitation of Holocaust suffering by perpetrators and their cultural inheritors, by non-survivors, by survivor-impersonators, and even by survivors themselves, the act of narrating even a single detail of the Shoah seemed to raise profound moral problems.

An article I came across by Naomi Seidman, a professor of Jewish Culture at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, traces how Elie Wiesel’s 1956 Yiddish memoir, Un di velt hot geshvign, (And the World was Silent), develops into his French and then English novel, Night.7 In the process of translation and revision, an existentialist memoir that indicted the world’s failure to respond to obscene crimes is transformed into the revered masterpiece that assails God. As Seidman stated in an interview with the Jewish Daily Forward, Wiesel “replaced an angry survivor…eager to get revenge and who sees life, writing, testimony as a refutation of what the Nazis did…with a survivor haunted by death.” The title change seemed to encapsulate the transubstantiation of the Holocaust into a theological event: the monumental crime the world failed to protest becomes the ultimate existential condition of darkness. The overlay of mysticism Night takes on is concentrated by the amplified themes of silence, which also dominate the mountain of commentary on the book: God’s silence in the face of evil, of events so obscene as to become, literally, unspeakable, events that robbed the murdered of speech. To this must be added one more type of silence. For if, as Wiesel argues, Auschwitz is “as important as Sinai,” then survivors become not crime victims deserving justice, but prophets on the level of Moses, to be met by the rest of us with silence and awe.

But the fundamental problem with sanctifying survivors is that it plays into the way the Nazis spin-doctored their crimes with Christianity’s stock plot, that people or societies are made pure via suffering. The prospect of injuring someone who has been abusively misrepresented is abhorrent; at the same time, the first portal to understanding an other is to try to empathetically project yourself into his or her life. Taken to its logical conclusion, the premise of Holocaust theology implies that no writer who is the beneficiary of a power differential ought dare to imaginatively construct a member of a less powerful group, that Plath ought not have written her poem, “Daddy,” because it uses Nazi images as analogies for a relationship between an American father and daughter, that Tolstoy ought not have written Anna Karenina.8 But surely the plain, ruthless, terrifying test of whether a white should be allowed to write a novel about a black, whether a man can depict a woman, or a free American can imagine a second-generation Jewish survivor, is whether the author does it well, whether the author’s understanding of the character convinces those he or she purports to represent.9 Indeed, spending years writing about a person you hold cultural power over can be some of the most laborious moral work of all, the fundamental work of recognizing an “other.” Tolstoy intended to rain judgment upon the adulterous Anna, but his narrative revised itself into empathy as he came to fully grasp how few options a thinking woman in that society had.

In search of physical evidence, I travelled to Terezín. But apart from the museum and a few Nazi street designations, the town looked like the other run-down towns I had wandered through to get there. Still, all over Europe, the battle for the story was still being waged. Sudeten Czechs were still lobbying for German reparations, which had not yet been agreed to because the descendants of the Sudeten Germans, a powerful Bavarian lobby, wanted the Czechs first to apologize for the violent Czech expulsion of the Sudeten Germans after the war. Handling the plastic slip over the Theresienstadt stamp a Prague dealer tried to sell me, I shuddered at its pastoral peacefulness, at touching this tiny artifact from the locus of evil—until my Czech friend, an expert, rolled his eyes, clamped on my elbow, and led me out. It turned out that the stamp is one of the most often faked pieces of Nazi memorabilia, that what I was looking at was a crook’s encounter with a color printer. I found Naomi Seidman’s careful scholarly analysis of Wiesel posted on a website of French deniers as its banner of proof that Wiesel was a liar, the Holocaust a hoax. A revisionist claimed Zyklon-B had never been used at Auschwitz, and sued historian Deborah Lipstadt for assailing him. Then the case of Swiss writer Binjamin Wilkomirski erupted.

Wilkomirski called his book, Fragments, a novelized memoir. It had none of the daily grit, the petty happiness, the texture of inconsequent life so evident in Imre Kertesz’ brilliant account,Fateless. But it stood as a haunting assemblage of incantatory shards about a boy in a camp, and was powerful enough to be translated into nine languages. Wilkomirski’s purported personal history was soon assailed by a second-generation author who had published a book about the same time that was widely ignored, and who resented the attention Wilkomirski was getting. A battle ensued that exposed Wilkomirski as a survivor impersonator, and generated comparisons with the case of Helen Danville, the Australian writer who posed as Helen Demidenko to publish The Hand That Signed the Papers, a novel that explained Ivan the Terrible of Treblinka by imagining him as a Ukrainian Christian child whose family was burned alive by Soviet commissars, who all just happened to be Jews.

Fragments was taken out of print, and Wilkomirski became a symbol of moral turpitude and the World Jewish Conspiracy. He was said to have made huge amounts of money—which the sales figures never substantiated—on his hoax. But whether or not he exploited the Holocaust, the man was tortured enough to be able to convey a boy’s terrible odyssey in the spare language of pain, and to write scenes I still remember years later. Reading the book had brought back a recurrent dream I had as a child, not in our family’s worst moments but in the quiet spells between, of desperately trying to crawl out from under our broken furniture to fly away as the sound of Nazis marching got louder. One thing the sheer number of people still processing the Holocaust tells us—the deniers resisting the inherited guilt they cannot cope with, the traumatized survivor-impersonators who cannot recognize a historical entity larger than their own pain, the historians shoring up dams of facts against cultural and institutional mythologizing, the German legislators who have made denying Auschwitz a crime, the Israeli politicians, enacting policies that redefine the term post-traumatic-stress, and the children of survivors (and of Nazis) working to invent lives in a void of information—is that if the Holocaust can be used by anyone, it also has the power to warp any vulnerable psyche that gets caught in its wake.

4.

At home, I began to watch oral histories on videotape. But at the U.S. Memorial Holocaust Museum in Washington, a passing comment made by a survivor in a cafeteria line made me understand how constrained the taped narratives were by the interviewers’ documentary agendas. I too had an agenda; what I needed was life. I asked the Museum to send out a blind query, a letter from me to all the Theresienstadt survivors they had on record, in which I explained my project. If they were interested, survivors could write their name and phone on a stamped postcard and mail it back.

As I waited for their return, a network of survivors revealed itself around me. I learned that two elderly residents of my forty-eight-unit building had been refugees who had lost their entire families. An old friend offered the story of her survivor-uncle teaching her how you crawl under a barbed wire fence (on your back, with your hands wrapped in rags, to keep from getting cut). And the postcards began to pour in—amazingly, I received nearly forty cards from all over the world. The generosity, the willingness to dredge up old horrors, seemed extraordinary. A widower sent back the card and denied knowing anything about his deceased wife’s internment; then, from another city, I received an anonymous package containing a xerox copy of her hand-written Theresienstadt diary, complete with accounts of exhausted trysts in the alcoves of Theresienstadt’s walls.

Kertesz writes of the prisoners’ greatest fear, that the truth of history would not be told and recorded. Fifty years later, that anxiety was palpable. After an interview with a woman in Denver, a therapist in Buffalo who ran a survivor group that included the brother-in-law of the Denver woman called the next morning at eight. Her client had heard that I was writing about a Russian in Theresienstadt, she said, and wanted me to know that there were no Russians in Theresienstadt. Flustered, I displayed what “credentials” I could muster, explaining that as I’d written it, my narrator’s father, who was half Czech, had emigrated to Czechoslovakia in the thirties with his family and been naturalized there; that I had located him in Theresienstadt because he was a renowned pianist who had been picked up in Prague. She said, “I’ll get back to you,” and the line went dead. I spent the rest of the day in an uneasy sweat, as if waiting for airport security to check a suitcase whose contents I suddenly could not vouch for. But I never heard from her again.

If I passed muster, my witnesses poured out their tales of rape and murders, of disease and starvation and squalor, of casual aggression and pointless humiliation, and of kindness and creativity amidst it all. If the person was bitter I could join their energy, fueled by anger and by a vague sense that I was performing tikkun by belatedly sharing their righteous outrage. But stories told plainly and softly, by those who had shed their carapace, induced a heavy, passive helplessness, a disgust at the inadequacy of writing books that end up on sidewalk tables. When I stumbled on material that sparked, the complacency evaporated. The feeling was always the same: the hairs on the back of my neck would stand up as yet another horrible detail dropped the floor out from under me, from under my notion of the inhumanity of which human beings are capable. Then the rush of pathos was chilled by the writer going to work, knowing I would use the detail. As the frisson faded, revulsion set in.

For a while, the horror stories satisfied a desire I suppose most traumatized people have, to have others confirm that the world is as bad as you feel it is. But as the summer wore on, I went from one artists’ colony to another, slipping down a steep slope of depression from the cumulative toxins my spirit was absorbing. Detached from friends and family and habit, I spent long mornings in bed reading first-person narratives, while simultaneously idly wondering whether it would hurt to drop a blowdryer in my bathwater. Did my increasing revulsion towards the stories I was hearing signal the smug denial of someone who can afford not to hear them? An alarm going off in my psyche? Or a healthy discomfort with the realization that I was vicariously feeding off others’ misery? But in a way, isn’t using other’s suffering what fiction writing is? Or does witnessing become use, and use abuse, the minute the witness picks up a pen?10

Always, before, I had written my way out of despair. But the fundamental evil of the Nazi’s storytelling were the myths with which they robbed their victims of their humanity and individuality. Ringing in my head that summer was a line from Vico I have never forgotten, that every metaphor is a little myth. I was standing in a burning building in the middle of minefield, and I did not dare take a step.

Then I came across a remark in a book, that all of the suicides the author had known had immersed themselves in the Holocaust for months before their deaths, and caught my breath, forced to admit to myself what the rope I had casually bought the week before, and tossed in the trunk of my car, was for. The sheer fascination with how low humans could go gave way, and my survival instinct, threatened by so much blackness, began to detach. My listening changed. In the stories of survival, the concatenations of “miracles” that concluded in an affirmation of the existence of a God interested in saving one life only, in the attempts to salvage a theodicy from the Holocaust in the founding of Israel, in the fables I was reading in Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust—anecdotal proofs of God’s omnipresent goodness amidst the grim Nazi backdrop—I now heard happy endings that seemed as absurdly upside-down as the motto Arbeit macht frei on the gates of Auschwitz.11

From one day to the next I decided that, for me, the Holocaust itself fell flat as fictional material. The dramatic structure seemed all wrong. The Nazis hit victims like a deus ex machina out of a Greek play, doling out terrible arbitrary fates that made character almost irrelevant. But no matter how hard I tried to steer the interviews with survivors into the present, from the Nazi evil, to how they coped with it, there I drew a blank. The Holocaust completely overshadowed it. Whether or not they were accurate—the work I was reading about the unreliability of memory was undermining my ability to trust even simple statements—the stories I heard were fixed and uninterruptable, like old recordings needing to be heard to the end. By August, I was forgetting the phone appointments I had set up. I saw little hope of completing my novel.

The last person I called was a woman whose father had been the deputy mayor of a mid-size German city until he was deported. Like the others, she had a tough-as-nails edge of bitterness; but though she was eager to supply me with whatever details might be useful, she maintained a regal, unsentimental posture.

“Na, ja,” she said, in a thick accent, “It wasn’t that bad.” Her father had died, she said, but he was sick. She had sung in the children’s choir. A few years after the war she returned to her city, and they gave her a medal. Singing in the Theresienstadt choir had given her an introduction to music she never otherwise would have received, she said. Her biting, sardonic tone sliced the sentiment out of whatever she recounted, and she made mincemeat of what she called “career survivors,” the people who published cookbooks of Theresienstadt recipes, and the like. In our next conversation I asked about the meaning of being Jewish. “I am a German,” she replied. “Only the Nazis made me a Jew.” “You were never tempted to explore your religion?” I asked. “All what I know of being Jewish is the Holocaust. Not the most inviting initiation.” She had visited Germany several times, so I asked if she had ever returned to Theresienstadt. She told me a story of crawling around the crematorium there, looking for its brand name, buried in the grass.

Though she was impeccably polite, her steady, assured tone convinced me that my interest was lurid, my desire to explore Holocaust trauma a waste of time. I wanted to thank her for driving the last nail in the coffin of a dead-end book, but I was too ashamed to tell her that her time had been so wasted. So as our last conversation wound down, I said that if I were ever to publish, I would mention her in the acknowledgements.

For the first time, the conversation came to a dead stop. “That, never,” she finally said, her voice suddenly hard.

“Fine,” I said, “but I’m curious, why not?”

“My daughter was a cellist,” she began.

In all the hours we had spoken—I had told her the plot of my book—she had never mentioned children. Now a story nearly identical my narrator’s poured out. The gifted daughter was homeless, and mentally ill; though she had some college education, she was now living on the street, dragging her cello with her. For several years she had called only occasionally. “It is nonsense,” the mother said dismissively. “She refuses to seek treatment because she knows what ‘they’ do to people like her.” If her daughter were to come upon her mother’s name in a book, my confidante was sure that her daughter would sue us both for having stolen her life.

I hung up, stunned. I had been researching the Holocaust the way children listen to the horror in the tales of the Brothers’ Grimm: lured in and chilled by somebody else’s terror, happy to be safe. Now, by accident, I had stumbled upon the edge of a clearing, the clearing my confidante had circled around for twenty hours of conversation. It was the site of my original questions, about how you choose the lessons of self-protection to take with you from a catastrophe. Now the question took on an almost terrifying urgency. For there seemed an almost inverse relationship between how far away my confidante had pushed her trauma, the flatness of her non-story, and the frightening inner life that had grown in her daughter. Now I had permission, not just because I imagined that daughter to be the person I was writing for, but because not speaking, the subject of my book and problem of its writing, could have consequences as devastating as speech. After years of preparing, I wrote the end of my book in four days.

5.

In a way, all childhood can be seen as a version of Stockholm Syndrome, the process by which a person who has been abducted comes to sympathize with and take on the world view of his captors. The recognition of utter dependency on an unreliable caretaker is too terrible to bear, and the only way to adapt—to order one’s universe—is to adopt the narrative that makes such impossible conditions necessary. All parents have undigested trauma—by Freud’s definition, trauma is exactly that which cannot be assembled into narrative form—that they keep from their children. But the things they harp on, prohibit, or caution against cast shadows, like those in Plato’s cave, of a world that needs to be coped with. In the case of the second post-Holocaust generation, the beast casting the shadows was huge. Often the survivors’ task—of protecting themselves from the trauma of the past, while protecting their children from knowledge of it—was simply impossible.

What does it mean to be a child of Job? Children who cannot understand distant, unavailable parents try to connect by fantasizing into the void. The psychological literature about the second generation abounds with young children who starved themselves, who interned themselves in tiny spaces, who reproduce the conditions of their parents’ trauma, so as to come closer to their parents and understand the reason for their suffering. The phenomenon, which a psychoanalyst named Bergmann coined “concretisation,” is defined by psychoanalyst Ilany Kogan as the compelling unconscious need children have to recreate and relive the parents’ traumatic experiences, as if these were their own stories.12 In Kogan’s renowned account of eight case studies of the children of survivors, The Cry of Mute Children,13 she documents second generation children of survivors who have themselves operated on, destroy relationships, or accidentally kill their own children, because they are living out—or fighting against—some imagined scenario from their parents’ lives. Reading Kogan, it was hard to know what was the most disturbing aspect: that survivors could pass on the trauma of the camps, even while trying to protect their children from it? The way the second-generation children, trapped in their parents’ time, could continue to damage themselves and others? Or the Herculean task of the analyst, charged with luring her patients back into the present?

More than anything else my book turned out to be about the task of living after trauma, about accepting that there is no mastery of the past, or another’s experience, while also facing the stark ethical imperative that is adulthood: to extricate ourselves from the warped narratives we inherit in order to avoid doing damage to others in the present. I wrote my way out of a past that was not my own by hurling myself back into its reality, in a process not unlike that of the second-generation children Kogan describes. Did I have the right to enter the survivors’ territory, to try and renact the scene of the crime? Imaginatively entering another’s emotional world is the basis of all fiction. But whether it is ethical depends on whether the writer also takes on the job of the analyst—if that empathy yields not just a fusing, but a blunt recognition of how different that other is.

In the history of story, the ways the Nazis mythologized their demons, and disorted and obliterated their versions of events, stand as the ur-caution of the damage narrating an other can do. The question of who has permission to write another is irrelevant. Writers write themselves free of what holds them captive. The trick is not to take captives in writing the story that sets you free.

Notes

1 Terezín was known mostly for its political prison, which held Gavrilo Princip, who triggered World War I by assassinating the Hapsburg heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

2 Wiesel, “Trivializing Memory,” from his From the Kingdom of Memory: Reminiscences (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 166.

3 These were leftovers; objects of any value were sent to the Reich.

4 See Frantizek Benes, Mail Service in the Ghetto Terezín, 1941–1945 (Prague: Profil, 1996).

5 Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Assassins of Memory: Essays on the Denial of the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992).

6 1I use “catachresis” in its Quintilian interpretation, as a way to adapt existing terms where an appropriate term does not exist.

7 Naomi Seidman, “Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage,”Jewish Social Studies (Fall 1996): 1-21.

8 See James E. Young’s probing discussion of Plath in Writing and Rewriting the Holocaust: Narrative and the Consequences of Interpretation (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990).

9 A recent review assailed black novelist Colson Whitehead for placing a heroine and not a hero at the center of his subtle, sharp allegory on race. But surely the problem with The Intuitionist was not that Whitehead dared to add gender to his cultural analysis, but that he didn’t explore it enough, did not recognize how different a female character actually would be.

10 Hayden White discusses the problem in great depth in “Historical Emplotment and the Problem of Truth,” in Saul Friedländer, Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the “Final Solution” (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992).

11 Yaffa Eliach, Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust (New York:Vintage, 1998).

12 M.S. Bergmann, “Thoughts on the super-ego pathology of survivors and their children”, in M.S. Bergmann and M.E. Jucovy, eds., Generations of the Holocaust (New York: Basic Books, 1982), 287-311.