On August 9 of last year, in Ferguson, Missouri, a white police officer named Darren Wilson shot to death an unarmed black teenager, Michael Brown. Immediately after this tragic event eyewitnesses provided conflicting accounts of what transpired between the officer and the young man. Some said Brown raised his hands, signaling submission to the officer’s authority, but was nevertheless gunned down execution style, his body left to rot in the street. On this account the killing and its aftermath illustrated the racist contempt with which too many blacks, especially young males, are treated by too many police. Others offered accounts more or less consistent with Wilson’s contention that Brown attacked him while he was inside his vehicle, attempted to wrest away his gun, and ultimately was shot in self-defense. On this account Brown could be seen as yet another dangerous predator posing a threat to his own community and to police charged with maintaining security there.

A grand jury was convened to determine whether Wilson should face criminal charges. The jurors deliberated for more than three months, reviewed forensic evidence, and heard testimony from dozens of witnesses including Wilson himself. In the end the jury determined that the physical evidence and the most credible eyewitness testimony supported the officer’s story. They declined to issue any indictment, fueling angry and sometimes violent protests, including arson and looting. In the days following the non-indictment and the unrest it unleashed, a great national debate over the fairness of America’s criminal justice system has ensued, pitting the interests of residents in “communities of color” against the prerogatives of the (mainly white) law enforcement personnel deployed to maintain order there.

Once again a high-profile but disputed encounter on the streets of an American city has become the site for a national debate over issues of race, order, and social justice. This is, in my view, an unfortunate and unproductive state of affairs. The case of Michael Brown should not frame our deliberations on racism and public order. A stark conflict of narratives in an unavoidably ambiguous factual context may set the stage for considerable drama but is unlikely to yield progress toward the reconciliation of two irrefutably legitimate claims: first, all American communities must be kept secure from the depredations of violent criminals; second, all Americans must be treated with dignity and respect by the law enforcement officers they encounter on the streets where they live.

Making Brown a poster child for a social justice movement might be a profound mistake.

Both claims express fundamental requirements of social justice: the residents of disadvantaged and marginal communities, too often people of color, also deserve public order and individual protections. But, as a practical matter, these imperatives are in tension. Maintaining order in dangerous communities is bound to engender some conflicts between the police and the residents of these places. Achieving social justice today means both acknowledging the moral force of these claims and remaining open to the complex and troubling social realities to which they apply.

We are a long way from doing either. Our current ways of thinking involve a series of binaries that, in my view, preclude a reasoned weighing of the two basic moral imperatives. A precondition for having a serious and effective deliberation about policies, laws, and practices is, on this argument, to dispel such simplistic ways of thinking.

I have in mind three unhelpful and obfuscating dualisms:

(1) Individual versus collective responsibility. The findings of the grand jury suggest that Brown was the aggressor in his encounter with Wilson, and that the officer acted in self-defense. Yet, if you ask what Michael Brown may have done wrong in this situation, many will say that you are blaming the victim. At the same time, if you ask about the social conditions that contribute to lawbreaking in the many disadvantaged communities of color such as Ferguson, and about the ways in which police sometimes abuse their authority, you are absolving their residents of responsibility for their wrongful acts and failing to treat them as moral agents. Why should we have to choose between, on the one hand, recognizing the role of disadvantage in leading some people to break the law, and, on the other, holding individuals accountable for their wrongful acts? We need to hold both thoughts (individual and collective responsibility) in mind at the same time if we are to fashion ethically acceptable responses to the severe social inequality and significant public disorder in some quarters of our society.

When people rob or assault others, they should be punished for it. But the question of justice does not end with apprehending transgressors and holding them accountable. Instead social justice requires acknowledging that, where transgression is widespread, responsibility is not confined to the people caught in traps of poverty, poor schools, joblessness, and segregated ghetto conditions. Responsibility extends to all of us. Through law and policy, society is collectively responsible for conditions that foster crime. Saying this does not mean that people lack the will to make their own choices. It is simply to observe that any group of people subject to such unacceptable conditions would be more likely than otherwise to transgress normative boundaries many of us take for granted.

(2) Pigs versus thugs. For many in Ferguson and elsewhere, the cops are racist pigs, bent on harming innocents. For others, the police are public servants doing their best to cope with the thugs they will encounter under impossibly difficult conditions. But reality is messier than this binary allows. Some neighborhoods are tough for police to work in—and for people to live in. They are dangerous and harbor dangerous people. At the same time, public safety is the product of police working together with community residents. It is undeniable that public safety is undermined when police show contempt for the people they are sworn to serve and protect. Hence law enforcement personnel working in these neighborhoods are responsible for treating everyone they encounter with dignity and respect—regardless of their race, age, gender, demeanor, and economic status. Indeed, the police are servants of all of the people—even the ones who don’t speak particularly good English, who haven’t had a job in three years, who hang out in front of a store with a forty-ounce beverage in a brown paper bag, who can be found in the alleyway smoking a joint, who have just come home from a three-year stint upstate. That is the job they signed up for. If we all started from the premise that cops are essential and that cops are responsible for the safety and respectful treatment of everybody, we would be in a much better place. These communities need the police to defend them from criminal victimization. And the police need the trust of the communities where they work in order to do their jobs effectively.

So it is a terrible state of affairs when the police view the community with contempt and when residents view the police as the enemy. This would appear to be the case in Ferguson today and, in no small measure, this circumstance reflects a failure of policing practices there. When breakdowns of this kind occur, the police and their political overlords bear primary responsibility for fixing the problem since they are the public actors with the capacity to introduce systemic changes in the employment, training, advancement, discipline, and compensation of law enforcement personnel. But community leaders—whether religious figures, elected officials, political activists, or public intellectuals—also need to do what they can to set matters right. They should pause long and hard before helping to poison the well by encouraging a narrative that defines the police as inevitable enemies.

(3) Gentle giant or public menace? Through press leaks, long before the grand jury’s findings were announced, we learned that Brown, just prior to being killed, was caught on tape apparently committing a minor robbery at a convenience store. It was also disclosed that he had marijuana in his system when he died. These disclosures seemed to have but one purpose: to discredit Brown, to cast him as a thug, the type of person who could have attacked Wilson. That is, the leaks were design to strip him of the presumption of innocence.

At the same time, Brown has been described by family members and advocates as a “kid” on his way to college and a “gentle giant.” Outrage over the purported murder of this innocent kid is meant to catalyze a movement on behalf of racial justice.

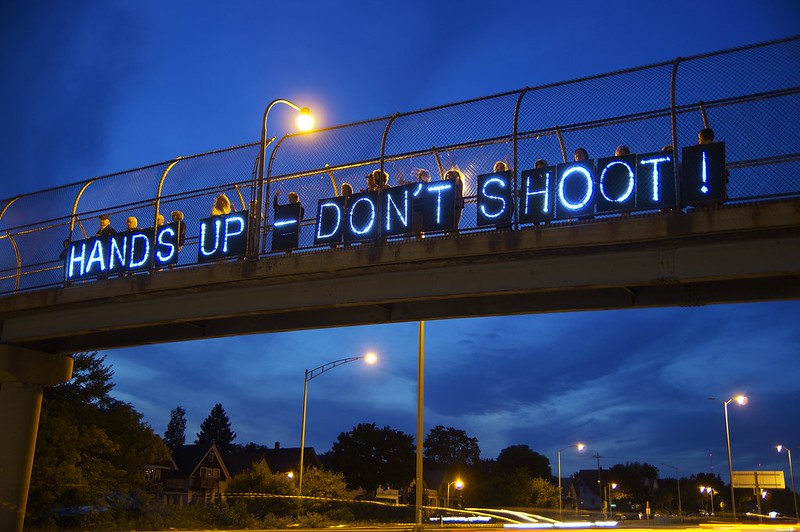

Thus activists from across the nation have been drawn to suburban St. Louis to join the demonstrations. Youngsters who see themselves as threatened by belligerent police have converged on Ferguson to show solidarity with the struggle. Parishioners from liberal churches, synagogues, and mosques have been sent to bear witness, pray for peace and demand that justice be done. “Hands up, don’t shoot” is their mantra, indicating their innocence—taken to be continuous with Brown’s innocence—and giving voice to their righteous fear of violent victimization by the forces of law and order.

But we need to ask just what the innocence claim is doing here. Brown need not have been a choirboy for his shooting to have been unjustified, if that had been what the evidence showed. By the same token, if he assaulted Wilson in such a manner that shooting him was a reasonable act of self-defense, this would in no way nullify the legitimate demands of protestors that people of color be treated with dignity and respect by the police. The innocence claim, it appears, is being deployed in an attempt to turn this case into a signifier of much broader social concerns—such as high black incarceration rates, the routine profiling of young men of color, the use of heavy-handed police tactics in minority neighborhoods, and the inequalities of race and class that set the background for these issues.

But making Brown a poster child around which to organize a movement for social justice might be a profound mistake, for doing so creates a situation where the success or failure of that movement hinges on the facts of his case.

• • •

While the idealism and engagement evidenced by the people vigorously protesting Brown’s killing is heartening, I am haunted by a profound sense of disquiet. In light of these three interfering dualisms, we can see clearly that the civil rights challenges we now face are more complicated than those of the past, and no one episode such as this can now crystallize a movement for racial justice. To quote a bumper sticker slogan I can’t shake from my mind, “Mike Brown is no Rosa Parks.”

I refer, of course, to the heroine of the Montgomery bus boycott, who on December 1, 1955, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white patron and move to the back of the bus in conformance with Jim Crow segregation laws. Her courageous act of defiance catalyzed the transformation of American politics. I fear that Brown’s tragic demise holds no such prospect for those of us who labor today on behalf of the cause of racial justice in American society.

Rosa Parks’s protest targeted a law. Brown’s death provides no such path to change.

For one thing, a well-organized movement already existed when Parks refused to give up her seat. That movement was poised to make use of the incident. No such movement exists now. More importantly, the problem of legal segregation at mid-twentieth century was qualitatively different from the current problem of police violence. Today there is no legislative agenda activists can point to as a plausible remedy for the conditions we all lament. Civil rights protests in the classical mode are therefore bound to fail here.

Structural problems—too few jobs, concentrated poverty, failing schools—are the root causes of conflict between the forces of law and order and the residents of high-crime neighborhoods. These deep problems of structural poverty are not, at the end of the day, issues of race at all. These problems cannot be remedied until whites as well as people of color recognize that we are all afflicted by a common set of maladies. Blacks need allies to organize and advocate over the long run for progressive policy reforms. Burning Ferguson to the ground is no way to get them.

I don’t look forward to a future in which cases such as Brown’s represent the black struggle for equal standing within American society. To be sure, an event of this kind can channel energy into collective action on behalf of needed reforms. For this reason many well-meaning people who long for change have seized on Brown’s death as a golden opportunity to organize. But the facts giving rise to the protests are important. In Brown’s case, as the grand jury’s findings confirm, those facts are sources of trouble, as they would be in just about any similar situation.

The issue is not the presumed personal character of individuals—that Parks was an upstanding churchgoer, a pillar of her community, and that Brown evidently was not. Nor do I intend to blame the victim, to suggest that Brown deserved his fate. Rather, my concern is whether his case can be a viable focal point for change within the limits of ordinary politics, whether protests resulting from Brown’s death can lead to real improvement in the quality of American democracy and to changes in the lives of people in places such as Ferguson.

Parks’s protest targeted a law. Responsibility for changing that law was clear, as was the moral conviction at stake.

Brown’s death under ambiguous circumstances provides no such path to change. Indeed, the reactions to it have every prospect of leading to further entrenchment of the status quo—not just because Brown seems to have been the aggressor, but also because issues about crime, policing, and poverty cannot be addressed in the ways that traditional civil rights issues could.

• • •

The black freedom struggle is in deep trouble today. It is in danger of losing its way—of becoming irrelevant. With Jim Crow a distant memory and black political influence waning as other minority groups—particularly Latinos—have grown, the conditions that gave rise to the mid-twentieth-century movement have dramatically changed. The tropes and dramaturgy of an earlier era—deployed today by the likes of Reverend Al Sharpton—come off as dubious and unconvincing anachronisms. They persuade nobody who isn’t already persuaded.

The Civil Rights Movement is to some degree a victim of its own successes in dismantling racist laws and attitudes in American society. Despite the large challenges that remain, that success is reflected in the improved legal, moral, and cultural environment that black Americans now enjoy. The election and reelection of Barack Obama, our first black president, attests to this. Overt expression of anti-black racial antipathy would prove fatal to the career of a politician, prominent business executive, celebrity athlete or entertainer. Ours is not a “colorblind” or “post-racial” society, and it may never be. But the easy enemy of overt, de jure discrimination has largely been conquered. What remains is what some call structural racism—the tacit, de facto impediments that systematically disadvantage African Americans and others. The effects of de facto racism are not minor, but they also are not easily reached by anti-discrimination laws and not usefully illuminated by cases such as Brown’s.

What we face today are conditions and associated policy problems that are hard to remedy and are often morally ambiguous—for instance, conflicts between mainly white police departments and mainly black communities where violent crime often takes place. Frustrated responses to these conditions frequently trade on idealized portraits of deprivation. But arguments on behalf of change must be credible; they must be based in reality; they cannot rest on hyperbole or dubious historical analogy or the like-minded understandings of the politically correct. Arguments for less punitive law enforcement, more community-friendly policing, more public investment in the urban spaces where large numbers of black and brown people live, less suspicion of young black men—these arguments, to be effective and persuasive, have to acknowledge the realities of our time.

One of these realities is the high rate of violence in low-income minority neighborhoods. Violent encounters between police and black men are common in contemporary urban America—national numbers are, amazingly, unknown, but according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, in the eight-year period between 2005 and 2012, twenty-seven blacks and six whites were shot dead by police in St. Louis alone—in part because of racist policing, in part because of concentrated poverty, and in part because young black men participate in so much violent crime. In twenty-five of those thirty-three St. Louis cases, police claimed to have resorted to deadly force only after being attacked by the suspects.

The controversy over the shooting in Ferguson underscores the fact that the main source of the racial tensions in modern America is the tortured relationship between residents of urban black communities and the police there. This is, unavoidably, difficult moral terrain. Excessive police violence, born of contempt for residents, is a real problem. And racial profiling of law-abiding black people often poisons police-community relations. We should never lose sight of these truths.

But they are not the only relevant truths. It is also the case that violent criminal victimization occurs in inner cities, often at the hands of young black men. Such violence necessitates a vigorous police response. Yes, I want bankers punished when they steal from clients. Yes, I want public officials punished for violating the public trust. But I also want young black men punished when they undermine public order.

To be sure, some of the laws being broken in urban America are wrong. As I have argued elsewhere, we have over-criminalized on the drug front, and the impact of this punitive moral crusade on people of color has been disproportionate and devastating. That racial injustice demands correction. Moreover, many of the low-income, poorly educated black and brown people caught up in the criminal justice system would not be there if they had better legal representation and economic opportunities. Their transgressions often carry negative consequences that are out of line with the severity of their misdeeds, considerably weightier than what befalls middle-class white youngsters committing the same acts. In many tragic true stories, lack of money, contacts, and legal sophistication costs the freedom and life prospects of a young person from the wrong side of the tracks. These palpable manifestations of social inequality, which too have a racist aspect, need to be remedied.

These realities—of routine minority victimization by the criminal justice system and the need to maintain order in poor minority communities—don’t map easily onto the Ferguson protests. The larger social critique of law enforcement in American cities and its impact on people of color is not well served by Brown’s painful example. That leads to hyperbolic claims about police looking to gun down innocent black teenagers because of the color of their skin, claims that don’t advance the political task at hand when the evidence suggests they are not true. Demands that prisons be abolished because too many blacks are locked up, complaints that today’s war on drugs is the functional equivalent of yesterday’s Jim Crow, acts of violence directed at law enforcement in the name of resistance—these, too, are politically harmful if the aim is to persuade a majority of our fellow citizens of the need for reforms.

If we want to see fundamental change in this area of public policy—where the state’s monopoly on the legitimate use of force collides with a community’s legitimate demand that order and security be maintained without contempt, alienation, and oppression—then we shall have to tread into some difficult territory. This is the territory where we reckon with the sources of disorder in too many American communities—including transgressions disproportionately enacted by black people. Where such transgression is the norm, people live in fear for their safety, and police officers know they could end up in life-threatening situations. These are not fantasies in the minds of law enforcement officers and residents of communities afflicted with violence, but fears inspired by real events. Righteous demands for racial justice such as those now echoing from protests in Ferguson can be compelling, but not if these fears and their factual bases are implicitly or explicitly denied.

This, it seems to me, is an argument that has to be made over and over again until it prevails. There are no shortcuts. To require that Brown be memorialized as a choirboy and Wilson demonized as a racist monster—to require, more generally, that the scourge of incarceration in black communities be understood as the rampant arrest of people who have done nothing wrong, who are the victims of police, prosecutorial, and judicial racism—is to start out with two strikes against oneself. The goal of moving our troubled democracy toward racial justice won’t be achieved through caricature and denial.