In Leo Tolstoy’s novella The Kreutzer Sonata, the time is the 1880s; the place, a train traveling somewhere in Russia; the situation, a middle-aged man with glittering eyes is telling a stranger the true story of why he killed his wife. His tale, in essence, is a diatribe against the immorality of marriage as he knows it.

Men such as himself (of the landowning class), he argues, are raised to lead idle lives of brutal appetite—drinking, gambling, whoring—from which they need to be saved. Women like the narrator’s wife are raised to exploit the weakness behind these appetites because they (the women) must marry. Each is making instrumental use of the other. No matter how we mask it with the claim that marriage is a union of love and purity, it is in fact a contract between a whore and a client. “If we only look at the life of our upper classes as it is,” he cries, “why, it is simply a brothel.”

On his honeymoon the narrator realizes that when not in a state of sexual passion, he has nothing to say to his wife. Absorbed by his own shock and disappointment, it isn’t until the third or fourth day that he sees how depressed she is. She cannot say why, but she feels “sad and distressed.” The trouble begins when he dismisses her complaint as childish:

She immediately took offense . . . . She told me she saw that I did not love her. I reproached her with being capricious, and suddenly her face changed entirely and . . . with the most venomous words she began accusing me of selfishness and cruelty. I gazed at her. Her whole face showed complete coldness and hostility, almost hatred. I remember how horrorstruck I was . . . . I tried to soften her, but encountered such an insuperable wall of cold virulent hostility that before I had time to turn round I too was seized with irritation and we said a great many unpleasant things . . . . we were left confronting one another in our true relation: that is, as two egotists quite alien to each other . . . . I did not understand [at the time] that this cold and hostile relation was our normal state.

Repeatedly, this couple will quarrel, make love, quarrel again. Soon enough, the periods between quarrels grow short, and yet shorter:

In the fourth year we both, it seemed, came to the conclusion that we could not understand one another or agree with one another. We no longer tried to bring any dispute to a conclusion. . . . As I now recall them the views I maintained were not at all so dear to me that I could not have given them up; but she was of the opposite opinion and to yield meant yielding to her, and that I could not do. It was the same with her.

These last are the telling sentences.

To read The Kreutzer Sonata after one has read the diaries of both Sophia and Leo Tolstoy is to realize two things simultaneously: one, the story line (except for the murder) is very nearly a transcript of daily life inside the Tolstoy marriage; two, the marriage itself is something that Dostoevsky more easily than Tolstoy might have written. In Tolstoy’s writing we have characters who, at once in thrall to both inner limitation and the force of circumstance, are placed on a landscape of world-and-self that steadily widens and deepens. In Dostoevsky we have these same characters living so completely inside their own heads that the world narrows down to the claustrophobic and the surreal. The Tolstoys, in the flesh, could not live out the “Tolstoy” within themselves. Equipped with all the external privilege necessary to live an open, expansive life, they were nonetheless driven to live as though Dostoevsky was making them up. The “happily ever after” of marriage had done them in.

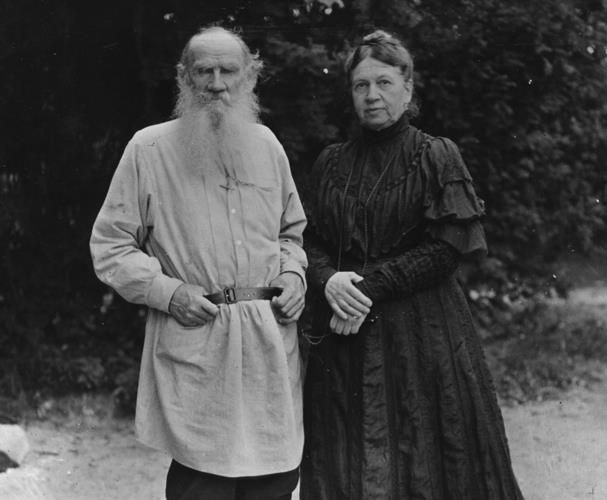

At the time of their nuptials, Lev Nikolayevich, by then a recognized writer, was a 34-year-old count who had lived a good fifteen years with the contradictions of character familiar to all readers of literature: on the one hand, he was a gambler, a drinker, a whoremaster; on the other, a breast-beating penitent who preached love, poverty, and humility, but made his family miserable, lived in luxury, and couldn’t get enough of his own growing fame. For the mass of Russians he would become a saint; for church and state, a devil; for Maxim Gorki, a figure of genius and disgust whose humility was “hypocritical and his desire to suffer . . . offensive!” In his early 30s, Tolstoy already wanted desperately to be saved from himself.

Sophia Andreyevna Behrs was the eighteen-year-old daughter of Andrey Behrs, a court doctor, and Lyubov Alexandrovna Behrs, a childhood classmate of Tolstoy’s. As full of intelligent high spirits as the Natasha of War and Peace, Sophia read, dreamed, larked about, loved music passionately, and fantasized conquering the world through marriage to a Great Man. Sonya (as she was known) could, in fact, have grown into a woman of sensibility and character had she ever had some real work to do. As it was, all she ever did have was the inherent sturm-und-drang of being married to Lev Nikolayevich. This would become not only her subject, but her organizing principle, her all-encompassing reality: the circumstance that nourished a richly talented arrest.

They were married in Moscow on September 23, 1862. Immediately after the ceremony, off they went to Tolstoy’s country estate, Yasnaya Polyana, where (except for winter visits to Moscow) they lived for the rest of their long lives. Here, Tolstoy wrote his books, took his walks, rode his horse, underwent his religious conversion, and held court to the world. And here, Sonya bore thirteen children, entertained hordes of visitors, copied out Tolstoy’s work (War and Peace six times), and eventually ran the estate herself. Good times were plentiful—parties, dinners, celebrations; skating, swimming, sleighing; musicales and performed readings; twenty people at the table every evening—yet almost none of them are recorded in the diaries where, in time-honored diary fashion, we read almost exclusively of the ongoing distress and discontent of two of the most strong-willed people who ever lived.

Neither got what they wanted—he wasn’t saved; she didn’t conquer— and neither ever got over not getting what they wanted. Each suffered an enduring humiliation thanks to the discrepancy between what had been expected of married love and what had actually been delivered. In this regard, the inexperienced girl and the worldly roué were remarkably equal. For both, a dream of fulfillment through marriage had originated in a place in the psyche that reached so deep that the dream’s failure to materialize was received as an insult to the soul. Feelings of wounded self-regard (on both sides) soon knew no bounds, and daily life at Yasnaya Polyana was approached with a mixture of attraction and repulsion that often excited thoughts of murder or suicide. Both Sonya and Tolstoy became obsessed to the point of dementia with the conviction that, at the hands of the other, each had been cheated of a destiny that would signify. Neither could have understood in advance of the marriage the depth of emotional ambition that motivated them, much less that it was precisely because that ambition was destined to be thwarted that each would be bound permanently, one to the other. It was the stuff upon which Sigmund Freud was to build an intellectual empire.

From the start, a pattern of explosive engagement established itself. Within days of the wedding they are arguing, and each is unaccountably depressed. In no time at all, she is weeping and he is storming about. Her speech is harsh, violent, hysterical; his harsh, violent, sneering. Reaching a climax of impassioned anger, they stare open-mouthed at one another, fall into each other’s arms, make hard sexual love, and—again in no time at all— withdraw once more into the mysterious sense of grievance that continually comes crowding back, each time more virulent than the last.

Tolstoy’s diaries are rich with gossip, book ideas, endless speculations about God and religion, and the struggle for his own soul. At the same time, the preoccupation with his marriage (the children never interested him) remains constant. As for Sonya, the world beyond her marriage hardly exists. Six weeks after her arrival at Yasnaya Polyana she begins to record the daily, weekly, monthly alteration in marital mood that will concern her—without stint, variation, or loss of energy —for the rest of her life. In the English-language version of her diaries, edited by Cathy Porter, each year begins with an editorial introduction that tries to set these lives in some social perspective. For instance in 1862, the year they wed, we learn that “Tsar Alexander II’s emancipation of the serfs the previous year ushers in the ‘era of great reforms.’” If we did not have these potted bits of history, we might imagine that Sonya and Lev Nikolayevich are living somewhere in outer space, so encompassing is the ongoing obsession with “the relationship.”

Over a period of more than 40 years Tolstoy used the diary to express, repeatedly and in one sequence or another, all of the following sentiments:

‘I love her so.’

‘I love her still more and more.’

‘Her character gets worse each day . . . [the] grumbling and spiteful taunts . . . frighten and torment me.’

‘There probably isn’t more than one person in a million as happy as the two of us are together.’

‘Women are people with sexual organs over their hearts.’

‘Seryozha [the eldest son] is impossibly obtuse. The same castrated mind that his mother has.’

‘Dreamed that my wife loved me. How simple and clear everything became! Nothing like that in real life. And it’s that which is ruining my life.’

‘She’s beginning to tempt me carnally. I’d like to refrain, but I feel I won’t.’

‘Women’s strong points: coldness—and something which they can’t be held responsible for because of their weak powers of thought—deceitfulness, cunning, and flattery.’

‘After dinner, Sonya said she’d been faithful and was lonely . . . I couldn’t say anything more. And I regret it.’

Over the same period Sonya wrote:

‘These past two weeks . . . I felt so happy with him.’

‘He disgusts me with his talk of the “people”. I feel it is either me . . . or the people. . . . If I do not interest him, if he sees me as a doll, merely his wife, not a human being, then I will not and cannot live like that.’

‘There is absolutely no evil in him, nothing I could ever dream of reproaching him for . . . I need nothing but him.’

‘He spends so little time with me now . . . when I feel young I prefer not to be with him for I am afraid he will find me stupid and irritating.’

‘I do not believe two people could be closer than we are. We are terribly fortunate in every way.’

‘We have quarreled and we haven’t made it up . . . . There’s such coldness, such a glaring emptiness and sense of loss . . . . What can I do with this love that has brought me nothing but suffering and humiliation?’

‘It was pure joy when he arrived [home] . . . . When I met him at the station he gazed at me and said, “How lovely you are! I had forgotten you were so lovely!”’

‘Wretched and lonely are the wives of egoists, those great men whose wives the next generation will turn into the Xantippes of the future!’

It pained Sonya throughout her life that her only real hold on Tolstoy was sexual—neither her thoughts nor her desires kept his attention—and it pained her even more when that hold loosened. She herself never enjoyed making love, but when finally, in significant old age, he stopped coming to her, she was beside herself with shame, loss, longing. So often, throughout their years together, he had bolted, leaving her entirely alone—sometimes even when he was in the house—for days or weeks on end (her diary often reports an unspeakable loneliness). Yet she had gone on dreaming that ultimately she would have Tolstoy’s friendship and tender regard. When the sex went, and the friendship did not blossom, she grew desolate.

Actually, they both did—he, too, craved a unity of souls—and the desolation deranged them even further. Here they are in their 60s and 70s, still pacing the floor at four in the morning, railing at each other (or at themselves), falling into exhaustion, then rising in a few hours to go at it again. One can almost see their heads repeatedly clearing out, then almost instantly filling again with blood. There seemed never a way to release themselves from the shock of actuality except through operatic convulsions—and this they indulged in until the very last. Tolstoy fled the house in the final weeks of his life crying out, as he had times without number, “I can’t take it any more! She’s killing me!” And Sonya, upon discovering that he was really gone, rushed out of the house (as she, too, had done times without number) to drown herself in the pond. When her daughter Sasha and a friend pulled her out just as she was going under, her first words to Sasha were, “Wire your father that I have drowned myself.”

The Tolstoys spent their lives warring with one another because simply to walk away from the ancient dream of two-shall-be-as-one was, for them, psychologically prohibitive. The association between spiritual significance and emotional fulfillment invited a metaphoric devotion that neither could resist. In sacred desire was to be found the majesty of something that lovers were, categorically, pledged to redeem: man’s forfeited nobility. To feel transformed by romantic passion was to see with radiant clarity the meaning of humanity as it could and should be. Indeed, the worship of love, realized or denied, aroused in both Sonya and Tolstoy the sense of paradise gained or lost that haunted every nineteenth-century romantic.

Millions of marriages, from time immemorial, have made their peace with the discrepancy between what should have been and what actually was, but for the Tolstoys such a truce proved viscerally impossible. The sense of loss that the discrepancy induced was, quite simply, unbearable. It is the “unbearable” that sets them apart. For them, it was necessary not only never to accept things as they were, but to remain relentless in one’s refusal to accept things as they were. To the last, one must go on shaking one’s fist at the heavens, crying aloud that the price of compromise is exorbitant.

That refusal is timeless and mythic; it is emblematic of a millennial yearning to achieve wholeness through the transformative ideal. If we give ourselves heart and soul to Love with a capital L, God with a capital G, Revolution with a capital R, perhaps we can be persuaded that what we fear most—our own incoherence—is not an immutable truth.

In the end the mixed nature of humanity itself proves the source of the great existential drama. To be mean and generous, depraved and decent, loving and murderous, not by turns but all at once—that, it seems, is the true burden of our existence. It is this humiliation that makes us rage at the heavens, this humiliation that has ever demanded of us some over-arching myth of redemption that will atone for the despair of our own self-divisions.

It’s a pretty safe bet, I think, that if love in marriage had not failed to dissipate the shock of his own nature, Tolstoy would not have wallowed so madly in the salvation dramatics of worldly renunciation. Sonya, too, badly wanted to be freed of her own tormenting contradictions but, solidly grounded woman that she was, Tolstoyan theatrics were beyond her, and for this, too, she suffered all the more. In 1908, at the age of 64, she wrote:

I have come in my old age to where two paths lie before me: I can either raise myself spiritually and strive for self-perfection or I can seek pleasure in food, peace and quiet and various pleasures like music, books and the company of others. This last frightens me.

As well it might have. She had long feared Tolstoy’s death because she knew that when he went she’d be bereft of their embattled attachment—the only means she had ever had of facing down the condemning terms of human existence itself.