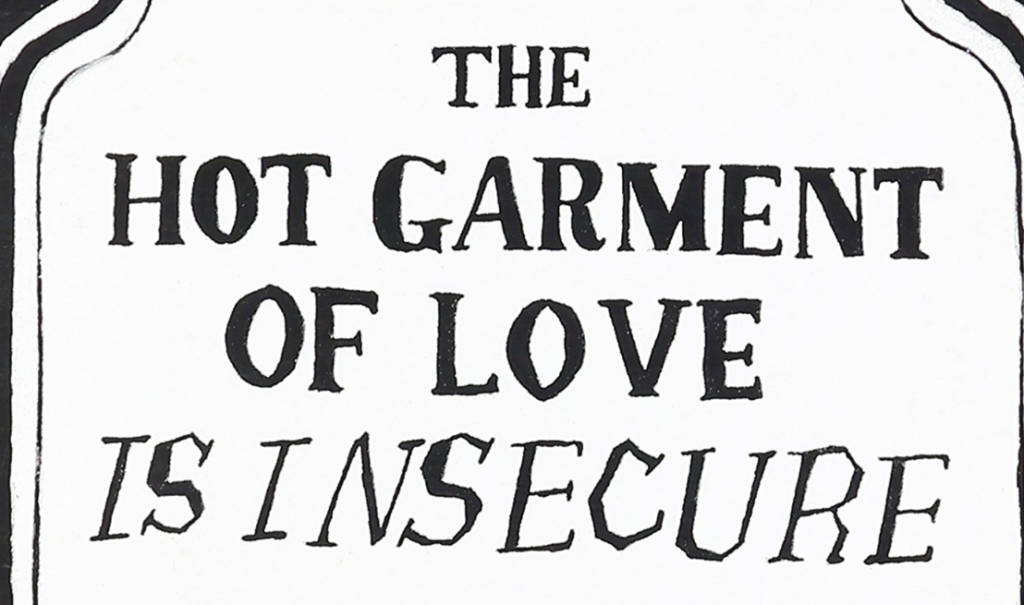

The Hot Garment of Love Is Insecure

Elizabeth Reddin

Ugly Duckling Press, $14 (paper)

Definitions of the obsolete verb “to knowledge” include not only “to own the knowledge of” but “to confess.” Elizabeth Reddin’s debut, The Hot Garment of Love Is Insecure, traces this relationship between knowing and confessing through the obsessive study of a single contemporary mind. Notably, Reddin’s confession is less memoiristic than histrionic, infused with dreamscapes, artifice, uncertainty, and self-reflexivity: “maybe it’s bad to follow your mind around, I keep following mine around in writing, I don’t know what my mind is so I follow it to learn more about who we are here and how to live.” The book contains two long poems composed of prose-like paragraphs alternating with verse and a third longer, diaristic piece written exclusively in paragraphs. The mind as self-destructive turbine and the risks of dependency on a beloved for affirmation are here documented largely unabashedly, but sometimes coyly: “I am so dry, I can hear the leaves getting dry outside, and me too, are all girls like that, I want to know.” Reddin’s imagery can shock, but resonates after its violence: “Flowers reach to the peak tops of every mountain and throw themselves lifelike from the crests.” If there is a desperation to this self-exam (“Sinking face up under the water and watching the surface, I can’t remember if we can see our reflection that way”; “Even a stream can seem senseless when your heart beats fast. // When you didn’t have a pen and paper how did you / remember anything”), there is also the satisfaction of emerging at the end with mind intact. The book opens and closes with the narrator contemplating green grass: “When you’re lying with your head in the grass it looks green to you if you’re thinking about green,” and “I . . . rolled onto my side, focused on the little green grass blade tips, their smallness calmed me, I felt their world was mine too, I watched a tiny bug traverse confidently and I was soothed.” The mind still buzzes and veers, but ultimately can find comfort and confidence in its singular ability to interact with the world.