How much can schools improve the life prospects of children growing up in poor neighborhoods? This question has divided the education community since at least the 1960s, when a group of researchers led by James Coleman attempted to quantify the extent to which segregation hurt black children. Coleman concluded that differences in family background had a greater impact on student achievement than did differences in school quality.

Almost 40 years later, former New York Times education columnist Richard Rothstein revisited the question. In a series of lectures at Columbia University’s Teachers College that became the book Class and Schools (2004), Rothstein chronicled the ways in which out-of-school factors undermine low-income children. Poor kids arrive at school knowing fewer words; live in substandard (often lead-poisoned) housing; lack health care; spend afternoons, weekends, and summers in neighborhoods without decent parks or libraries; face discrimination in the workplace after they leave school; and so on. This part of Rothstein’s argument was not new to anyone familiar with the lives of poor children. But he made one additional claim that upset many educators. According to Rothstein, the challenges facing low-income students meant that they would always do worse, on average, than their higher-income peers.

I devoured Class and Schools when it came out; it seemed an urgent call for our nation to address out-of-school factors holding poor children back. Others saw (and see) Rothstein as defeatist, apologizing for school failure and telling inner-city teachers and kids that they will never beat the odds. The argument erupted again last year when two groups of education reformers set out what were widely seen as competing agendas. The Education Equality Project—led by New York City schools Chancellor Joel Klein, Washington, D.C. schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee, and minister-activist Al Sharpton—emphasized school accountability, tough standards, and changes in how teachers are hired, fired, and paid. The other group, formed by the Economic Policy Institute (Rothstein’s home), called for a “Broader, Bolder Approach,” insisting that schools alone cannot be expected to successfully educate poor students. Schools need help, they said, in the form of expanded health care, afterschool and summer programs, quality early childhood initiatives, and the like.

Although the rhetoric from the two camps does not always reflect it, the gap between them is narrowing. Two important new books on schools suggest it should narrow further still.

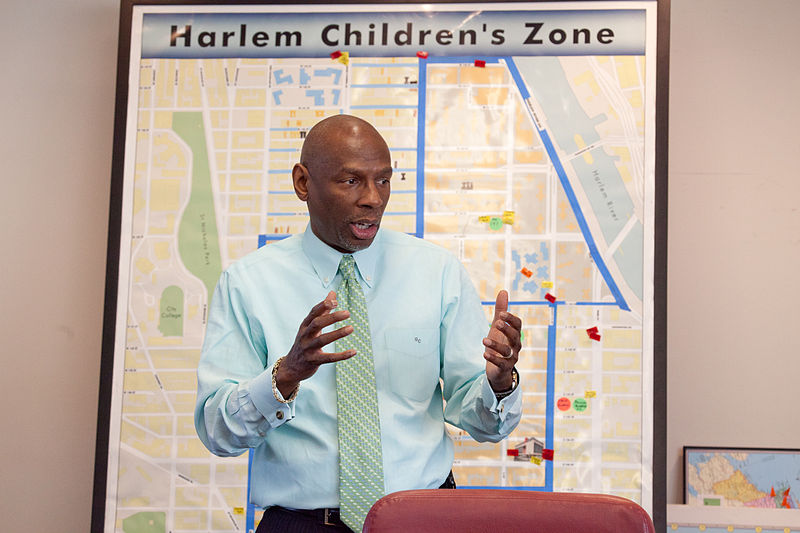

Canada describes Harlem Children’s Zone’s social programs as a ‘conveyor belt’ taking children from cradle to college.

Geoffrey Canada, the subject of Paul Tough’s Whatever It Takes (2008), has affinities with both camps, but his approach to the problem of urban poverty feels comprehensive in ways that would especially please Rothstein. Canada (with whom I serve on a nonprofit board) started out as director of the Rheedlen Centers for Children and Families, which offered a range of programs to Harlem youth, including truancy prevention, afterschool tutoring and drop-in centers, and anti-violence initiatives. The programs helped, but after a few years Canada realized something was missing. He grew tired of saving a few kids in his afterschool program while the rest of the neighborhood remained poor and violent. Piecemeal was no longer going to work.

So in 1997 Canada started the Harlem Children’s Zone (HCZ), an extensive network of social programs that includes parenting classes, health clinics, and tutoring centers that serve children and families in a 97-square-block area of Harlem. Canada had read the same research that Rothstein had, and used the findings to create a plan of action. Do Harlem kids arrive at kindergarten with cognitive deficiencies? HCZ responds with Baby College, where parents learn to read to their children, take them to museums and libraries, and ask open-ended questions instead of issuing commands. Canada believed that he could raise poor children’s academic performance by providing their parents with the same child-rearing advice—about discipline, nutrition, and cognitive development—that is so readily available to middle-class parents.

Canada describes HCZ’s social programs as a “conveyor belt” taking children from cradle to college. The children of Baby College graduates would enroll in Harlem Gems, a prekindergarten program that emphasized language skills. When they were ready to start public school, they would find HCZ staff in the building, providing reading programs, computer labs, and other supplemental services. By partnering with existing schools, Canada hoped to ensure that the impact of his early interventions did not “fade out” over time.

To his dismay, however, school principals did not always welcome HCZ’s efforts. Moreover, Tough writes: “Even in the schools where the programs were running smoothly, they didn’t seem to be producing results: the neighborhood’s reading and math scores had barely budged.” So Canada decided to create a charter school of his own.

Tough’s book begins on the April night in 2004 when Canada held a lottery to admit students to his new Promise Academy. The primary grades were open to students who had benefited from HCZ’s early intervention programs. But in a decision that would prove fateful for his project, Canada also created a middle school that was open to all comers. Roughly a third of these students were soon found to have “serious learning issues.” And this 30-odd percent, Tough writes, generally shared two other characteristics: they had “disengaged parents” and they “made trouble in the classroom.” Members of Canada’s board took to calling these students “bad apples.” But Canada was unwilling to expel them. They reminded him of young men whose pictures he kept on one wall of his office—his first karate students when he had started working in Harlem in the 1980s:

They had come to him unstable and angry and eager to fight. He had taught them martial arts and mentored them through one crisis after another; he drove them in a rented van to tournaments all over the Northeast. He had lost some of them, to gun violence and prison and drugs, and those losses still haunted him. But twenty years later, most of them were now thriving—college graduates holding down decent jobs.

‘There are some kids up on that wall that there was no way they should have gotten through college,’ Canada said. ‘But you can get them through.’ He leaned back in his chair and looked up at the faces in the photos. ‘Now, if you’ve never done it yourself, then, absolutely, you can look at certain kids when they’re eleven and think, “This kid can’t make it.” You do think that—until you’ve actually taken some of those kids that everybody else has said can’t make it, and you help that kid make it. And once you’ve personally made it happen, you never lose that. You see that kid as a grownup, going on with his life, and you think, “How many kids like this one have we thrown away?”’

In addition, Canada wanted the younger children at Promise Academy to grow up in a place where older kids served as positive role models. Every eleven-year-old who “made it,” Canada believed, would help change the expectations and atmosphere of the neighborhood. This was his “contamination” theory—his vision of how to transform a community as well as individual lives.

Acting on this vision, Canada and his team tried everything they could think of to make the middle school work. They replaced struggling teachers and administrators, rode herd on faltering students, and adopted stricter discipline policies. They expelled a student with extreme behavior problems. They also surrounded the middle schoolers with the types of services—including medical care and counseling—that Rothstein’s book calls for. Still, while Canada could see improvement, the test scores did not reflect it initially—at least not for the oldest students.

Eventually, under tremendous pressure from his board (one of whom feared that another year of low scores would damage “the Harlem Children’s Zone brand”), Canada made a wrenching decision: he would not open a ninth grade as planned. The troubled eighth graders would graduate and be helped to find other schools, and Promise Academy would refocus its efforts on the younger kids, those whom Canada’s programs had had more time to shape.

A few months later, however, a final set of test scores for the eighth graders came in. They were stunning. Whereas less than 10 percent of the students had been on grade level in math when they arrived three years earlier, now 70 percent were. It turned out that even bad apples could achieve.

As impressive as the Knowledge Is Power Program school I visited seemed, it looked to be all-black…. It is a tragedy that we have taken integration off the table.

In what is otherwise a hopeful, inspiring book, the decision to give up on the eighth graders at Promise Academy is the one heartbreaking moment. But the episode contains an important lesson: Canada’s initial instincts were correct. The eleven-year-old who never got the benefits of Baby College or Harlem Gems still needs a school that is caring and rigorous, and can still draw significant benefit from it. And we have an obligation to provide such schools to children who did not make it onto the conveyor belt at the outset—even if the odds of their succeeding are longer.

My colleagues and I at the Maya Angelou Public Charter School in Washington, D.C.—an alternative school for students who have struggled academically and otherwise—have learned this from experience. When we see students who are years behind in school, who have dropped out or been locked up, we might be able to say that only a certain percentage will graduate from college. But a percentage does not show up at your doorstep; Denice, or Jason, or Ashanti does. And we can never tell in advance whether any particular kid will make it. Like Canada, we have been surprised too many times to make predictions. So until our society guarantees that no child misses the conveyor belt, there have to be places that offer young people a second chance.

• • •

During Promise Academy’s darkest days, Canada’s board kept pressing him to turn the school over to an outside group—the Knowledge is Power Program, or KIPP. Canada did not relish the prospect. According to Tough, Canada saw KIPP as operating a “dueling model.” KIPP, Canada thought, did not seek out the most troubled students. Moreover, its goal was to take those kids who could survive its strict program and lift them out of a troubled community, whereas Canada saw the school as part of the larger community and wanted to transform them both.

The KIPP schools are the favorites of what has been called the “no excuses” side of the school reform debate. These advocates dispute Rothstein’s claim that school reform depends on community revitalization. Stephen and Abigail Thernstrom, for instance, point to KIPP as proof that schools can enable children to overcome the disadvantages of growing up in a poor family or community. Recall that James Coleman and his team took schools as they were and found that their impact was limited relative to family background. Coleman never said that it was impossible to create a school—or a network of schools—so extraordinary that it could make poor children competitive with their more privileged counterparts.

Jay Mathews’s book about KIPP, Work Hard. Be Nice., is the story of extraordinary teachers creating extraordinary schools. As Teach for America recruits in Houston in 1992, Michael Feinberg and David Levin were dumb enough to think they knew it all, humble enough to quickly realize they were wrong, and lucky enough to have great mentors to show them how it was done. In his first year of teaching, Levin was lost, but across the hall was Harriett Ball, the building’s legend. Ball gave Levin and Feinberg much of what have become KIPP trademarks, including the songs, chants, and raps that fill the air, the frenetic pace that teachers maintain as they work the room, and the relentless approach to discipline that forces students to focus on the consequences of each action, no matter how small.

When we see a program flourishing, it is easy to assume that success was inevitable. But watching Feinberg and Levin build KIPP—which now runs 66 schools in 19 states and the District of Columbia—reminds us how hard, and unlikely, success can be. KIPP started as a tiny program within a single Houston school, and, in the early days, the founders often found themselves fighting obstructionist, closed-minded administrators (of course there were some dedicated and constructive administrators, too). Some of KIPP’s battles with the powers that be were silly: when Feinberg posted motivational signs outside his classroom, the principal objected because he had not gotten approval for the specific adhesive used. Others were serious: administrators instructed Levin to exempt certain low-performing students from the statewide assessment, fearing that the students would fail and drag down the school’s reputation. When Levin refused, he was fired, despite having previously been voted the school’s teacher of the year (and despite, as it turns out, having been right—the kids passed).

With administrators like these, it is no surprise that the original proposal to create a KIPP school-within-a-school was not well received. When Feinberg and Levin offered to recruit 45 students and work with them for longer hours (at no extra pay), the district balked because it could not decide whether this qualified as “curricular reform” or an “after-school program.” Finally, Feinberg and Levin turned to another of their mentors, Rafe Esquith, who advised them to be polite toward the bureaucrats. But what if they still refused, wondered Levin and Feinberg. “Work around them,” Esquith said. “Do it anyway.”

Levin and Feinberg took something else from Esquith: his work ethic. Esquith started thinking about his kids at 5 a.m. and did not stop until 11 p.m., and he was often with them on weekends and over the summer. This attitude is built into KIPP’s structure, which includes a longer school day (nine hours), a longer week (three hours every other Saturday morning), a longer year (a three-week summer school), and a great deal of homework (one to two hours a night). Kids are expected to call teachers if they need help with an assignment. KIPP schools are full of slogans, but they all revolve around Esquith’s core motto: “There are no shortcuts.”

Mathews’s enthusiastic account of KIPP schools contrasts sharply with the descriptions by KIPP critics. Skeptics have three concerns about how the schools operate. First, that in the effort to achieve high test scores, the schools sacrifice creative thinking in favor of a drill-and-kill approach. Second, that the structure is too rigid. Third (and related to the first two), that any program employing a distinctive approach for poor and minority children should be viewed with suspicion. According to Tough, this last concern was paramount to Geoffrey Canada. If the middle class is told that “children in Harlem need their own special category of educational practices, they will get the message that those Harlem kids are ’not like us.’”

In response, Mathews invites critics to spend time in a KIPP school. Persuaded, I chose unscientifically among KIPP’s three schools in Washington, D.C.

I originally wanted to see Saturday school because it fit my schedule best. Ms. Almagor, my teacher contact, told me her Saturday assignment was to go horseback riding with seven of her students. I liked this school already, and suspected that Rothstein would, too. Here was an activity that could bolster the students’ self-confidence and their awareness of the world beyond their neighborhoods: just the sort of activity that Rothstein says poor kids need and are routinely denied.

But I really wanted to see classes, so I turned up on a Thursday instead. The hallways were quiet—the loudest noise was from a teacher chastising students who were apparently not quiet enough. Students were in lines. And they were required to read, not talk, during breakfast. This level of structure does not fit my progressive sensibilities, but I tried to remain open-minded. Having attended some fairly chaotic urban schools, I understand the argument that a highly structured environment might be needed to make learning possible. As Mathews writes, the KIPP founders wanted to send a message:

School should be a place where students could feel safe from bullies and wise guys and acts of childish cruelty. . . . They strived to make KIPP an island of peace where children could speak their minds and tend to their business without having to defend themselves.

To somebody who got beat up almost every day in fifth grade, that sounds great.

But what happens inside the classroom? Mathews insists that KIPP’s critics are wrong to say that the schools emphasize rote learning rather than more intellectually challenging activities. In this regard, KIPP may have been ill-served by some of its supporters. So much of the media coverage about KIPP focuses on kids marching in lines or singing uplifting chants in unison. Such scenes play better on the evening news than a teacher-student writing conference, even if the latter matters more.

Based on my statistically insignificant sample of one school visit, Mathews is right. Ms. Almagor’s all-boys, seventh-grade English class was varied, fun, and sophisticated. Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun was the text, and the class opened with a period of silent reading, followed by group discussion (enthusiastic hands, participation from every corner, with Ms. Almagor calling on the few students who did not volunteer). Next the students broke into pairs, first to read aloud and then to act out a scene in small groups. The class concluded with “college-style discussion,” in which the teacher sat back and the students formed a circle and ran their own seminar. Procedurally, students were learning how to take turns, to respond to each other’s arguments rather than go off on tangents, and to disagree respectfully. Substantively, they were learning how to make an argument based on specific textual references (“Well, I disagree, because on page 154 Walter says . . .”).

This was a place of seriousness, study, and self-expression. A class where boys read, and were proud of it.

Throughout my visit, I was deeply impressed by the culture inside the classroom. Before the lesson began, I was peppering Ms. Almagor with questions in the hallway, so we arrived about 30 seconds late. When we walked in, every student was neatly tucked into his desk, eyes on whatever book he had chosen for the silent reading period. I moved to the back of the room and began reading myself, and after about 5 minutes I heard Ms. Almagor say to the class: “I respect the decision that you made on your own, without my saying anything. But with this particular visitor, I don’t mind.” At which point students stretched out, put their feet on desks, lay down on the floor, or clambered onto bookshelves. Having found their preferred reading perches, they turned back to their books. Ms. Almagor later confirmed what I suspected—the kids read every day and normally sat wherever they liked. But they adjusted their behavior for outsiders, because some visitors do not understand that thirteen-year-old boys lying on the floor reading are in fact learning.

This was a place of seriousness, study, and self-expression. A class where boys read, and were proud of it. (My favorite poster: a student-designed placard reading, “There are other schools. But we work harder.”) But not just that: this was a class full of boys who understood that to thrive in the world where KIPP aims to send them, reading and writing well are just the start. Knowing how people read you is equally critical.

• • •

As impressive as the school seemed, I left with one nagging concern: the school looked to be all-black, and, as the D.C. Charter School Board Web site would confirm, overwhelmingly low-income. Of course, that is true of the rest of the public schools in the neighborhood, but those schools are not being portrayed as models of reform. It says something important that the schools offered up as our best hopes are so completely segregated. It says even more that neither Tough nor Mathews feels the need to address the question of segregation in their books.

It is a tragedy that we have taken integration off the table. Perhaps I believe this because my parents—one black, one white—met in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and saw themselves as part of a struggle for an integrated, beloved community. Perhaps it is because I am still moved by Thurgood Marshall’s argument that our nation will only learn to live together when our children learn together. Or maybe it is because of my lingering fear that if poor kids are isolated in schools of their own, they will inevitably end up being shortchanged by a society content with massive wealth inequality. If we make schools better and improve the lives of some kids (or, in Canada’s case, a whole neighborhood) but do nothing to disrupt segregation, are we simply making separate a little more equal?

Despite these misgivings, I think I know how Canada, Feinberg, and Levin would defend their choice. I know it because, when I saw the terrible schools for jailed kids in D.C., I felt an obligation to help create a better alternative, even though I knew that almost every child in the school would be African-American and that most would be poor. I recognized the urgency of offering those kids the support and resources that no other program was going to provide. But I do not want to live in a society that accepts this situation as inevitable. And I am confident that Canada, Feinberg, and Levin do not, either.

If it is possible to make a great school for kids who deserve at least that, surely that is a worthy undertaking. And by this important measure, KIPP looks pretty inspiring. KIPP schools have posted the largest and most sustained learning gains across a network of schools that I have seen. Students who have been in KIPP for three years have moved, on average, from the 34th to the 58th percentile in reading on a nationally normed test, and from the 44th to the 83rd percentile in math.

The data about student achievement at KIPP have long been contested. (Rothstein is one of the doubters.) Some critics have suggested that less able students are leaving KIPP and thereby inflating the gains reported for those who remain. Others ask whether it makes sense to rely on test scores as the sole measure of student progress. And, most important, some question whether the documented learning gains will prove durable and translate into improved life outcomes for graduates. Mathematica Policy Research is conducting a five-year longitudinal study comparing KIPP lottery winners with children who entered the lottery but were not selected for admission. No doubt the results of this study will figure heavily in Mathews’s next book—a detailed examination of KIPP’s remarkable growth.

Assuming that KIPP is as successful as we all hope it is, what lessons can we draw from its story? Rothstein might say that even if the KIPP model works, it is exceptional and cannot be replicated on a scale that would bring about a general improvement in the academic performance and life prospects of poor children.

Mathews contends, however, that by demonstrating that disadvantaged kids can achieve at high levels, KIPP removes a critical obstacle to reform. “Many people in the United States,” he writes,

believe that low-income children can no more be expected to do well in school than ballerinas can be counted on to excel in football. . . . These assumptions explain in part why public schools in impoverished neighborhoods rarely provide the skilled teachers, extra learning time, and encouragement given to children in the wealthiest suburbs.

I would like to believe, with Mathews, that if you show that something works, people will support it. But do we really need more proof that poor children can succeed in school? Consider early childhood education. As Tough points out, we have decades of data about the benefits of high-quality programs for poor children. Yet we still do not provide enough spaces for all of the kids who need them.

Moreover, notice how much weight the words “in part” carry for Mathews when he writes, “these assumptions explain in part” why children in poor schools are shortchanged. What about power, race, class, stigma, and a desire to maintain positions of relative privilege? Surely they at least merit discussion as we speculate about why the poor get less. My list of alternative hypotheses could go on, and would not be limited to explanations that comfort liberals. Consider that a charter school network like KIPP can operate in 19 states only because charter school advocates overcame the opposition of liberal critics and teachers unions.

There are over 19 million low-income students in this country. That is the problem we have to solve.

Mathews also praises KIPP for proving that success can be scaled. After all, the KIPP network has grown from one school to 66—with plans to grow to aboout 100 by 2011—while getting better. That is a testament to what talented people can do, and is rightly celebrated. But we should be careful not to conflate the question of how KIPP will replicate its model with the very different question of what it will take to achieve KIPP-like success for all (or most) low-income students.

If KIPP expands as planned, it will serve 24,000 students in 2011. There are over 19 million low-income students in this country. That is the problem we have to solve. (Just to be clear, this is not KIPP’s problem—it is our problem.) What would it take to get KIPP-like quality for millions of children?

For too long, I am afraid, the answer has been to trumpet the success of a spectacular school or teacher and shout, “No More Excuses,” or “It’s Being Done.” But that alone will not work. Those responsible for consistently underperforming schools do not know how to get better. It is not as if teachers in bad schools have great lesson plans and are hiding them. People working in persistently underperforming schools have become demoralized to an extent that outsiders touting “best practices” fail to understand. Until we get smarter about how to help them improve through well-designed mentoring and professional development programs, little will change.

Even worse, the hard truth is that many mediocre teachers and administrators do not have the capacity to improve to anywhere near the standard required to achieve KIPP-like results. As much as it thrills us to read about extraordinary people succeeding with poor children, I want to see how ordinary people can do the same. Until then, we should hesitate before assuming that successful models will change the field.

If anybody doubts this, please consider two assignments. First, read Charles Payne’s So Much Reform, So Little Change. As Payne reminds us, there have always been some excellent schools. Before KIPP, there was Harlem’s Central Park East, which flourished under Deborah Meier’s leadership in the 1980s and 1990s. For many years, Central Park East was the icon of “what works” in inner-city education, and Meier’s account of the school in The Power of Their Ideas remains one of the wisest books ever written about teaching. But Central Park East did not revolutionize education, because efforts to transplant what worked there into schools with different cultures and less-skilled educators often failed.

Second, visit the human resources department at KIPP. There you will see an organization singularly dedicated to recruiting the best talent. KIPP knows that nothing is more important than the quality of the teacher in the classroom. So KIPP invests heavily in this area, and its brand, resources, and strong school leaders allow it to succeed. To say that KIPP gets a disproportionate share of the best young teachers is a compliment; it hardly diminishes KIPP’s success. But it does raise important questions about how we are to achieve KIPP-like success without a massive human capital improvement.

Perhaps the most important lesson we can take from HCZ and KIPP is this: the best programs are always innovating, refining, challenging themselves to do better by the students they serve. And for just this reason, the most successful reformers do not fit into neat ideological categories. Canada started out running social programs, but when he peeked inside Harlem classrooms, he quickly realized he could never transform the neighborhood without fixing the schools. Feinberg and Levin, by contrast, set about to change how a single classroom operated, but they learned that in order to succeed, they had to redefine the boundaries of what we call school. Today in Houston, KIPP is running programs for three-year-olds. In several cities, it now provides afterschool and summer school programs, individual tutoring, social workers for kids in distress, and, at some campuses, classes for parents. It is also actively involved in community partnerships that address families’ medical and other needs.

In response to the ongoing “fix communities” versus “fix schools” debate, those doing the work in the trenches increasingly are settling on a single answer: do both. As Ms. Almagor wrote me after my visit to her classroom:

In the long run, providing the dental care and (Lord knows) the family and parenting support is way more scalable and less leap-of-faith than the yes-we-can, sheer no-excuses, stubbornness-will-accomplish-the-impossible solution. Even our kids who are doing well are struggling against such preposterously unfair burdens. If we can make the job less impossible, we should.

She has it exactly right. She is willing to make the leap of faith; she does it every day that she walks into her classroom. But this is only part of the fix. The larger question remains: how can we justify making her work so hard, or the odds for her kids so long?

What we most need now—and President Obama’s recent education speech suggests he understands this—is for policy advocates to adopt some of the pragmatism that Canada, Levin, and Feinberg have shown on the ground. On the one hand, this means recognizing that poor kids will not routinely succeed until we build all the pieces—from cradle to college, in school and out—that Canada began with and that KIPP is adopting. It also means, as KIPP’s founders saw from the beginning and as Canada came to learn, that the conveyor belt does not work unless we acknowledge the failings of schools as they are, and transform them into places where excellent teaching and high expectations are the norm.