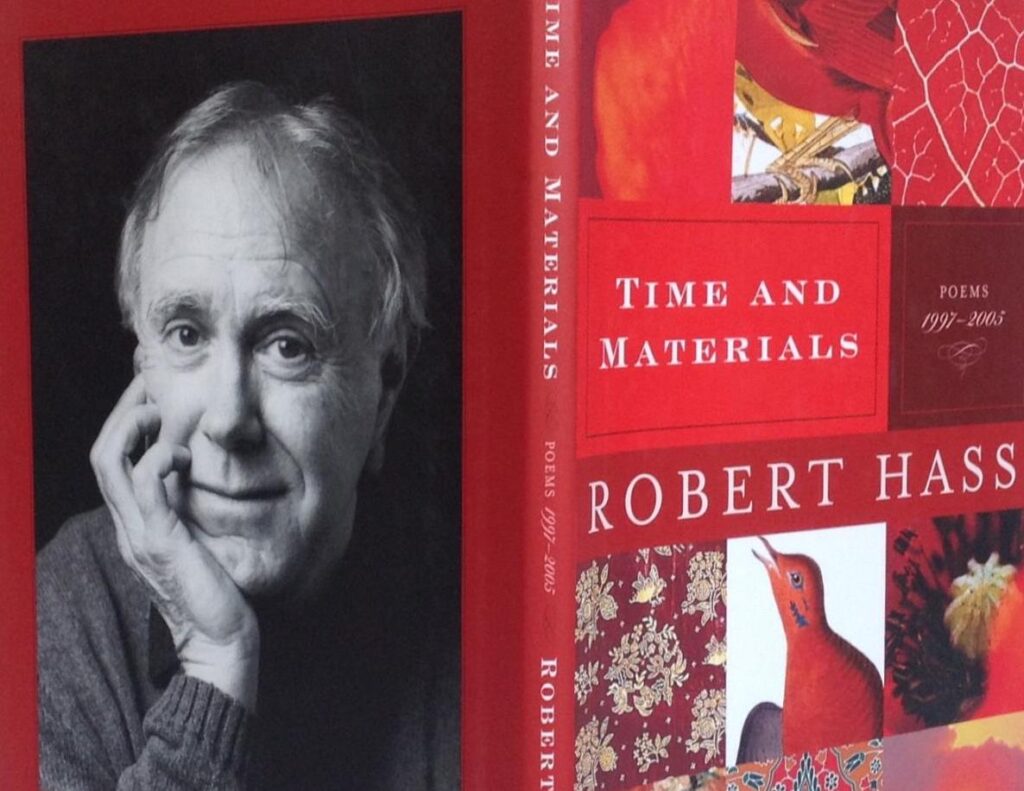

Time and Materials: Poems 1997–2005

Robert Hass

Ecco Press, $22.95 (hardcover)

Though the title of Robert Hass’s fifth volume includes a date stamp, the book covers far more time—and far more kinds of time—than the near-decade that appellation suggests. Here, Hass addresses everything from prehistoric protoplasm to global warming, alternating between imaginable people, who have the good sense to run across actual streets in real “October,” and persons who act real but then tell each other they “never existed inside time.” Personal and autobiographical material presages mythic meditation; ordinary human conversations rise out of dream-like landscapes; a particularly colloquial, present-tense poem about refulgent Berlin “in the pretty springtime” turns tense with a series of “flashes” back into historical atrocities. Time and Materials opens with a couplet about a farmer in Iowa. As the book concludes, four substantial poems about war convert colloquially blunt diction into the intensity of spoken oratorio.

So, we might say, the collection has range. And the way that every poem sets its own terms and creates its own moment of understanding, with its own sense of time, makes the book seem extraordinarily long. The reader is taught to read Time and Materials page by page, or moment by moment, rather than as a whole. That’s part of what makes it so companionable: the book wants to interface with you one-on-one, a desire it conveys in frequent conversations between pairs, romantic and otherwise. This conversation, from “Breach and Orison,” seems more than cute:

What would you do if you were me?

she said.If I were you-you, or if I were you-me?

If you were me-me.

If I were you-you, he said, I’d do exactly

what you’re doing.

Hass wants us in this book, doing, in some sense, what he’s doing. He believes in our power to be “him-him,” whether it’s in a dream or real life.

This suggests, however, that personhood does not belong entirely to us, that it may be little more than a thought or function of language. In a 1994 review of Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing, Hass wrote the following about that other, less jovial Westerner: “If (McCarthy) seems post-modern in his sense that everything is a quotation of a quotation, he parts company with post-modern practice in thinking, not that everything therefore refers to nothing, but that in human life certain ancient stories are acted out again and again.” Hass, too, seems to have an idea of ordinariness—in speech, action, and person—that threatens personhood with absence, even as ordinariness brings the poem back to lived experience. The persons in Time and Materials, often notable or noted by the poet for not paying attention to him, become quotations, amalgams, and ideas: “A student / Of complex mathematical systems, a pretty girl, / Ash-blond hair. I could have changed her diapers. / And that small frown might be her parents’ lives.” Yet this emptiness is the narrative we all inhabit, and even our anonymity is shared: “Desire that hollows us out and hollows us out, / That kills us and kills us and raises us up and / Raises us up.”

Hass recognizes his own emptiness in his inability to hold a personal narrative together. The vivid story about his grandmother in “The Dry Mountain Air” is therefore a tasty Hass treat: reading its details feels like being a child at Christmas (there are even Christmas cookies in the poem). But the poem becomes even more unbearably vivid when Hass reveals why he’s told the story in the first place:

My brother, four years older,

Says this never happened. Not once. She

never visited the house

On Jackson Street with its sea air and

the sound of fog horns

At the Gate. I thought it might help to

write it down here

That the truth of things might be easier

to come to

On a quiet evening, in the clear, dry,

mountain air.

In the more jocular and lazy “Old Movie With the Sound Turned Off,” the poet is unable to concentrate and thus, ultimately, unable not to make us concentrate, not on the movie or even on his train of thought, but on the uncanny final image and the knowledge “That the flower of the incense cedar / I saw this morning by the creek is ‘unisexual, solitary, and terminal.’” These endings are conclusively inconclusive. They consciously emphasize how the thinker is subject to drift; instead of making his world seem less real, they make him seem less real. Repeatedly in these poems, selves who think they are in control are disabused of that fiction.

This drift is predicted in some sense by the book’s title, which promises two distinct forms of poetic investigation. The first, narratives of “time,” are long-lined, endearingly inattentive stories that often smash together anecdotes (mostly of other people’s lives), artworks, and atmospheric meanderings. These poems see experience in motion and capture the mind in the process of observing itself, as we hear clearly in “After the Winds”: “My friend’s older sister’s third husband’s daughter— / That’s about as long as a line of verse should get— / Karmic debris? A field anthropologist’s kinship map? / Just sailed by me on the Berkeley street.”

The second variety, the lyrics of “materials,” cobble together much the same disparate kinds of information, but instead of the generous and long-lined sentences of the poems of “time,” they use silence as a suture; they are more lyrical, stranded in the moment, and full of images that don’t always move. As the speaker of the bric-a-brac “Twin Dolphins” remarks, “Eden, limbo.” Wearing a title taken from the middle of a poem by Louise Glück,“‘. . . white of forgetfulness, white of safety’” similarly begins with three seemingly unrelated narratives: “My mother was burning in a closet. // Creek water wrinkling over stones. // Sister Damien, in fifth grade, loved teaching mathematics.” Autobiographical detail lives in these poems to open possibilities, a heap of images serving as a hall of doorways.

If human experience is a series of distractions, Hass is ready to reframe them as necessary shifts in attention. This is the case in “Futures in Lilacs”:

“Tender little Buddha,” she said

Of my least Buddha-like member.

She was probably quoting Allen

Ginsberg

Who was probably paraphrasing Walt

Whitman.

After the Civil War, after the death of

Lincoln,

That was a good time to own railroad

stocks. . .

Some readers might find this particular moment of this particular lover’s tenderness a little cloying, but the point of the poem is that the lover can neither be blamed nor credited for the preciousness of her term of endearment for the speaker’s article of faith. After all, her quotation comes from another quotation, which comes from history, all of which is linked dreamily from one moment to another. The intimate interior takes shape through a list of associations, and the poem’s warmth and fragmentariness are one and the same sense, a strange melding of the personal and the referential. This suggests a crisis, that “the word is elegy to what it signifies,” as Hass says in “Meditations at Lagunitas,” one of his most famous early poems. But it doesn’t seem like a crisis anymore.

On the surface, Hass’s subjects are domestic, ordinary, and familiar: the terrain, for the most part, of autobiography. But his shadow-subject is the kind of threatening otherness that even California fairy tales possess: the opposite of tranquility. The frequent pairs in Time and Materials are marriages of a failed or different order, for the most part lovers in some way outside the world of marriage, lost, whether on a beach or beyond the pale, free but bickering, like an Adam and Eve who were never expelled from Paradise but discovered boredom anyway. Hass’s paradise-world never fails to recognize a hell, as at the end of “Then Time,” when a handless man propels himself into his ex-lover’s imagination of what makes life worth living. In the midst of a well-traveled sentiment, he finds an image of terror: “Death made it poignant, or, / If not death exactly, which she’d come to think of / As creatures seething in a compost heap, then time.” Looking back on the book, in fact, I find it full of images of hell, from the mother burning in the closet to flashes into the history of bombing. This is why Hass’s joyfulness feels oppositional and fought for.

In the same way, his sweetest moments occur when his voice finds itself challenged to shoulder its seriousness lightly. Hass can’t bear to exclude anyone, sometimes to the point of absurdity. “You know that passage in the Aeneid?” he asks in one poem. “You know that milkmaid in Vermeer?” he poses elsewhere. And it is voice that carries the bravest and, potentially, the most untrustworthy statement early in the book, in a poem entitled “Winged and Acid Dark,” which details the rape of a woman by German soldiers after the Second World War: “Pried her mouth open and spit in it. / We pass these things on, / probably, because we are what we can imagine.” “Probably” makes the idea tremble on the page. It keeps it undefended and therefore practicable rather than preached. Hass uses a hint of doubt to say that bare familiarity, represented by the colloquial, slightly wavering “probably,” is the only thing that one can use to bear horror. The drama of the line comes from Hass’s intense flexibility, the way that an episode that should seem outside familiar speech must necessarily be spoken of in a human voice.

Similarly, “Exit, Pursued by a Sierra Meadow,” which I take to be the best poem in Time and Materials, bears its darkness by fusing the personal and the philosophical into a voice at ease with itself, and especially with our inability to have complete knowledge:

Good-bye, white fir, Jeffrey pine.

I have no way of knowing whether

you prefer

Summer or winter,

Though I think you are more

beautiful in winter.

After all the rhetorical high-handedness of some of the political poems in the book, it’s lovely, and more politically affecting, to see the poet say “good-bye” to a tree. But Hass is still talking to an otherness, and he can allow himself to be so judicious only after he has asserted his ignorance. The poem ends with an image of dispersal (“August will squeeze the sweetness out of you / And drift it as pollen”), and in the book’s last drift it’s unclear whether Hass is talking about the trees or his readers. His meadow exists most to him in his dispossession of it, just as the neighborly sweetness of his voice isn’t ease but something “squeezed out,” an intimate reminder of the impersonal forces—call them time and death and politics—with which the individual life has to share the globe, and which don’t always feel so companionable.