Photograph: Vincent Brassinne

Photograph: Vincent Brassinne

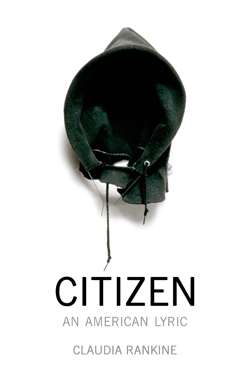

Citizen: An American Lyric

Claudia Rankine

Graywolf Press, $20 (paper)

Claudia Rankine delivers a spondee like a gut punch. Stressed monosyllables sound in pairs throughout Citizen like gongs of a Greek tragedy—ominous and riveting. The context is not overtly metrical, but watch what she does: “something unwilling, something wild vandalizing whatever the skull holds.” An unruly menace unfolds through a chain of “w,” “l,” and “d” sounds, accumulates into “ld”s, then drops with the force of “skull holds.” It is the impact, as she says of the weight of the past, of a “blunt instrument.” Spondees drive plot and conflict: “foot fault,” “head ache,” “hand held.” A string of them unleashes fear: “guard rail, spotlight, safety lock, airbag, fire lane, slip guard, night watch.” The Red Hot Chili Peppers know how to do this too (“steak knife / card shark / con job / boot cut”), but Rankine’s rhythms serve an ethical purpose—they are markers in an assay of the venom that is systemic racism. They mark an ongoing effort to write: “tried rhyme, tried truth.” They revivify idioms of anger: “Kin calling out the past like a foreigner with a newly minted ‘fuck you.’” They propel commands (“come on,” “move on”) and expose excessive punishment (“one guy,” “hey you”). Rankine’s spondees deploy the speaker’s pain (“head ache”), then worse (“chokehold”), then worse still: in the section about Trayvon Martin, after “pink sky” turns “bloodshot,” we hear it—“hey boy.”

In its relentless music and political relevance, Citizen is poetry written to a Horatian imperative: it delights and instructs—if by delight we mean captivate, if by captivate we mean hold the attention fixed. The elements are straightforward: prose paragraphs, interleaved with images, verse passages, and quotations, relate anecdotes of microaggressions and meditations on how racism is exhibited and internalized. It is a swift and gripping read. The chorus of praise the book has received, the prominent reviews and countless shout-outs in social media, the outcry when it did not win the National Book Award: all bespeak its timeliness as well as its accessibility. The book builds from accounts of misunderstandings to a body count, concluding with “situation scripts” that document a nation’s disasters and miscarriages of justice: Martin, James Craig Anderson, the black poor in New Orleans after Katrina. In the wake of Michael Brown’s and Eric Garner’s deaths at the hands of police, and the dismaying failure of grand juries to indict the police officers who killed them, the book’s relevance stands out in even starker relief, and even more numbing obviousness. “Everyday” racism does more than make people uncomfortable; it imperils lives.

In its relentless music and political relevance, Citizen is poetry written to a Horatian imperative: it delights and instructs—if by delight we mean captivate, if by captivate we mean hold the attention fixed. The elements are straightforward: prose paragraphs, interleaved with images, verse passages, and quotations, relate anecdotes of microaggressions and meditations on how racism is exhibited and internalized. It is a swift and gripping read. The chorus of praise the book has received, the prominent reviews and countless shout-outs in social media, the outcry when it did not win the National Book Award: all bespeak its timeliness as well as its accessibility. The book builds from accounts of misunderstandings to a body count, concluding with “situation scripts” that document a nation’s disasters and miscarriages of justice: Martin, James Craig Anderson, the black poor in New Orleans after Katrina. In the wake of Michael Brown’s and Eric Garner’s deaths at the hands of police, and the dismaying failure of grand juries to indict the police officers who killed them, the book’s relevance stands out in even starker relief, and even more numbing obviousness. “Everyday” racism does more than make people uncomfortable; it imperils lives.

The book’s reception also bespeaks its unnerving capacity to tilt the plane of critical inquiry itself. What does it mean for a white critic like me to “recognize” this book, in both senses—to see herself in it, to recognize in it feelings of shame, guilt, and anger, and then to do some part to bestow on it the status of literary success? The book’s excruciating narratives of racism in familiar settings—academic office, supermarket, restaurant—induce incredible anxiety. (Have I made these mistakes? Have I inflicted this kind of pain? I’m sure I have.) Citizen’s dominant grammatical mode is the interrogative, and its proliferating uncertainties preempt and ponder its own reception: “She said what? What did he just do? Did she really just say that? He said what? What did she do? Did I hear what I think I heard? Did that just come out of my mouth, his mouth, your mouth?” The hardest question Citizen asks may be the one it asks implicitly of the white critic or reader. If Hennessy Youngman’s videos “intimat[e] that any relationship between the white viewer and the black artist immediately becomes one between white persons and black property,” does the same thing happen to the relationship between white critic and black poet? Does writing this review lay claim to intellectual property, or cultural capital? Is white praise of Citizen a species of what Matthew Zapruder has called a “value brag” by readers who want to get their privilege-smudged fingers on this token, use it to take a ride out of their white liberal guilt? Where does privilege, and power, inhere? Rankine’s inquiries refuse to allow a reader to “lose herself” in this book.

The success of Citizen lies in its searing moral vision and reader-implicating provocations, and it does this work through its singular command of poetic resources. The book reminds poetry readers they do not have to choose between technique and content, concept and pathos, form and politics. To read this book is to yield to hunger for feeling (outrage and empathy and voyeurism and dread and shame), to bear witness to testimony that demands social change, and to encounter rigorous formal exigencies and structural principles. With its prose lineation and paragraphing, Citizen does not look to many readers and prize committees much like lyric poetry, even as it announces itself, repeating the subtitle of Rankine’s previous book, Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, as “An American Lyric.” “Lyric” is a notoriously slippery term, prone to be ahistorically and promiscuously over-applied. Here it means something not far from what T. S. Eliot meant—the mind speaking to itself, and the reader invited to overhear—but only if we take that notion by the throat and threaten to hold it underwater. Rankine’s lyric is meditative interiority plunged into ice-cold history.

The book opens wryly with a meta-poetic quip: the speaker is “too tired even to turn on any of [her] devices.” But in fact, Rankine has turned them all on, all the devices of figuration that poetry affords, or at least six of them: self-referential second-person address, metonymic verse paragraphing, allusion, metaphor, an extended body/text analogy, and ekphrasis. These devices are not the exclusive province of poetry (are any?), but in the aggregate they underscore poetry’s power to coalesce linguistic resources and verbal energy.

As many have observed, Rankine’s second person has a visceral impact because it simultaneously evokes intimacy and accusation, confession and complicity. The subjective “you” that trails the self, the “you” that stands in for the “I” and also telescopes the reader’s apprehension, provides an apt alternative to “Your ill-spirited, cooked, hell on Main Street, nobody’s here, broken down, first person.” Cracked open by the temporal deixis of “you,” the lyric space becomes a field of notice, expansion, and interrogation. In a prismatic interview with Rankine in BOMB, Lauren Berlant also uses the words “gut punch” to describe ways Rankine’s text can register physically for the “you” who reads it as well as the “you” who experiences its scenes of confrontation. Berlant observes that in galleys Citizen had slashes between each paragraph to demarcate scene changes. I read the book first in a review copy that included these slashes, and I wish they remained—as signs of rupture, overt signals of the anti-hierarchic power of placing these episodes one after another. Each piece of each story stands in metonymically for the omnipresence of oppressive ideology, and at the same time the adjacency of these stories suggests an architecture of resistance. Within these fields, Rankine layers allusions, a mode of precise textual decoupage—James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Maurice Blanchot, Frantz Fanon, Homi Bhabha, Shakespeare.

Is white praise of Citizen a “value brag” by readers who want to use it to take a ride out of their white liberal guilt?

Even her most traditional poetic devices, simile and metaphor, are viscerally felt. The virulent snarl of a woman, a therapist, caught in her own racist confusion, degrades utterance to the animal: “It’s as if a wounded Doberman pinscher or a German shepherd has gained the power of speech.” Equally potent in its connection to organs of breath and speech, the most quoted line of Citizen is the metaphor that clinches this passage:

Though a share of all remembering, a measure of all memory, is breath and to breathe you have to create a truce—

a truce with the patience of a stethoscope.

“Stethoscope” is the chilling vehicle for an emotional tenor, the “patience” required to broker this peace. (Eugenio Montale: “if this clear light signifies a truce, / the sweet threat of you consumes it.”) The noun and verb of the body’s sustaining substance and action—“breath” and “breathe”—become the terms of a tenuous peace, a treaty committed to acute listening, an act that in turn requires pause, forbearance. A stethoscope listens for rhythms, for arrhythmias: the clinician’s tool is a metaphor for the poet’s art.

More pervasive than Rankine’s use of metaphor is her use of an extended analogy. In many poems and sections, an analogy of body to text functions not as rhythmic counterpoint but as metaphysical ground: “the immanent you.” One might call this device a meta-poetic allegory of embodiment. One might call it écriture féminine. Pathos wells up from the textual body as the site of “the production of loneliness”:

Words work as release—well-oiled doors opening and closing between intention, gesture. A pulse in a neck, the shiftiness of the hands, an unconscious blink . . . . words encoding the bodies they cover. And despite everything the body remains.

Words encode bodies most dramatically in Rankine’s analysis of the racism targeted at Serena Williams: “the body’s positioning at the service line” subjects it to the ever-present risk of being called out—called out for blackness, called out on account of (that brilliant spondee) a “foot fault.” “Foot fault”—tennis error, poetic chasm—marks an axiomatic scene of racial performance and penalty: “The physical carriage hauls more than its weight. The body is the threshold across which each objectionable call passes into consciousness.” Serena’s body, gendered and racialized, becomes a text whose interpretation she herself cannot control: “her body, trapped in a racial imaginary, trapped in disbelief—code for being black in America.”

Over the course of the book, imagery of breath and laceration transfigure body into text and text into body. The physiologic response of the sigh—a resigned breath that is neither speech nor gesture but almost both—becomes a marker of pathology, woundedness, dis-ease: “the sighing is a worrying exhale of an ache.” A pyrrhic stutter—clusters of unstressed syllables—becomes a bruit in the pulse. The sigh becomes symptom of the stresses of racism, the body’s involuntary response (“you feel your own body wince”):

Every day your mouth opens and receives the kiss the world offers, which seals you shut though you are feeling sick to your stomach . . . the go-along-to-get-along tongue pushing your tongue aside.

The mouth and tongue struggle to produce meaning, to give voice to sickening rage, only to be policed by ingrained coping mechanisms and the world’s cruel and suffocating seal. The struggle is figured as an erotic violation, an unwelcome kiss resisted by a self-policing Philomela. In another episode, two women converse, one makes a cruel mistake, and “You both experience this cut, which she keeps insisting is a joke, a joke stuck in her throat, and like any other injury, you watch it rupture along its suddenly exposed suture.”

The body breathes and speaks, but it also sees. Citizen’s images invite the reader into a mise en scène of instruction—a method for re-teaching the gaze that is instructive but not combative: “It wasn’t a match, I say. It was a lesson.” Many images are arrayed in filmic sequences, parts of collaborations with photographer and filmmaker John Lucas (Rankine’s husband). As in Rankine’s earlier books, “the route is often associative,” and meanings arise from the effects of juxtaposition. One graphic talisman is Zora Neale Hurston’s line “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background,” mediated through Glenn Ligon’s 1991 painting where these words are repeatedly stenciled and increasingly smudged. The images in Citizen accrue to surreal effect, phantasmagoric stills in an epochal sequence: “plantation, migration, of Jim Crow segregation, of poverty, inner cities, profiling.” The book concludes with an image of the initiatory crime, J.M.W. Turner’s The Slave Ship, printed twice, the second time harrowingly in zoom—a detail of white fish attacking the slave. All the artworks Rankine spotlights trace their origin to this image of terror: a woman’s exposed back in efflorescence as if balm for flogging, a human-faced deer weeping pearls, the mosaicked, upturned face of a young black man—eyes closed in what might be bliss, or resignation, or agony past agony.

Citizen is a standout book, a book that might break out of the insular poetry world—I won’t call it a poetry ghetto, but yes, I had to self-correct—and reach exponentially more minds than most poetry books do. Rankine has pulled out all the stops (the idiom’s origin is the pipe organ’s capacity to play all tones at once). In the book’s final pages, the spondaic pace quickens—“him her us you me”—as if driven to tachycardic insistence that the message be heard, that the reader recognize the perilous cultural solvent of “simple, naked, and unanswerable hatred”—words of Baldwin’s that Rankine cites. I believe—I tell myself—I am writing this review to assist in some measure in getting this book into as many hands, syllabi, and newsfeeds as possible. I could also be writing it to jump on the bandwagon of endorsement because it gets me in touch with my white guilt, gives shape and outlet to my confusion in a zeitgeist of remorse and frustration. I could also have a misdirected faith in the power of a book to do extra-literary work, to be the thing to turn the tide. Do I sound foolish or self-indulgent clinging to that wish? I’ll chance it. The dread of the gaff is nothing to the dread of the bullet.