Poemas / Poems

Gerardo Deniz

Gerardo Deniz

Edited and translated by Mónica de la Torre

Ditoria/Lost Roads Publishers, $12.50 (paper)

Ditoria/Lost Roads Publishers, $12.50 (paper)

Mexican poet Gerardo Deniz's first passion in life was chemistry, and an interest in the sciences—including zoology, cartography, linguistics, and anthropology (he is a translator of Claude Levi-Strauss)—informs not only the content of his work—polysyllabic words abound—but the bemused "outsider" nature of his approach to life. Not unlike another poet with a science background, Gottfried Benn, or an avowed influence, T. S. Eliot, Deniz is often clinical and unflinching; yet the mundane, not to mention the shocking, sports freely among his more abstruse musings. "Auditor" reduces its protagonist, a somewhat sycophantic student, into a pair of steaming hands "cooked … in a thick sauce, the color of a sparrow, / with peas, mushrooms, nuts, capers," while "Dawn" recounts the pleasures of thinking about such things as the "biogenesis of picrotoxinin," only to conclude: "all this which we minor spirits do with major issues, / bites and penetrates reality (in case it means something) / a thousand times more than the sordid medicine kit of abstract powders, intellectualoid mouth washes, dialectic suppositories, / with names of thinkers (so many German, now also French) on their labels." There is a mythic quality to his imagination, but one which never leaves the realm of the physical even when considering abstract subjects, as when he recounts how he took "gluttony by a braid" and broke her leg—"it sounded (and felt) as if I were breaking a loaf of excellent bread"—or in the poem "Crime," which begins: "Every afternoon analogy takes her demon out to pee on deck." Deniz—born Juan Almela in 1934, in Madrid, the son of an exiled Spanish socialist and bookmaker—is undoubtedly a major poet, and for all of his erudition and uncompromising concision is supremely enjoyable, especially for lovers of intellectual tour guides of the possible like Borges and Ashbery. This bilingual selection, divided into thematic sections with titles such as "Freudian Poems" and "Poet in the classroom," has been beautifully translated by de la Torre, conveying the unique ironic tone and generous breadth of this poet who has been, until now, nearly unknown in the United States.

—Brian Kim Stefans

Brutal Imagination

Cornelius Eady

Putnam/Marian Wood, $24 (cloth), $13 (paper)

Cornelius Eady

Putnam/Marian Wood, $24 (cloth), $13 (paper)

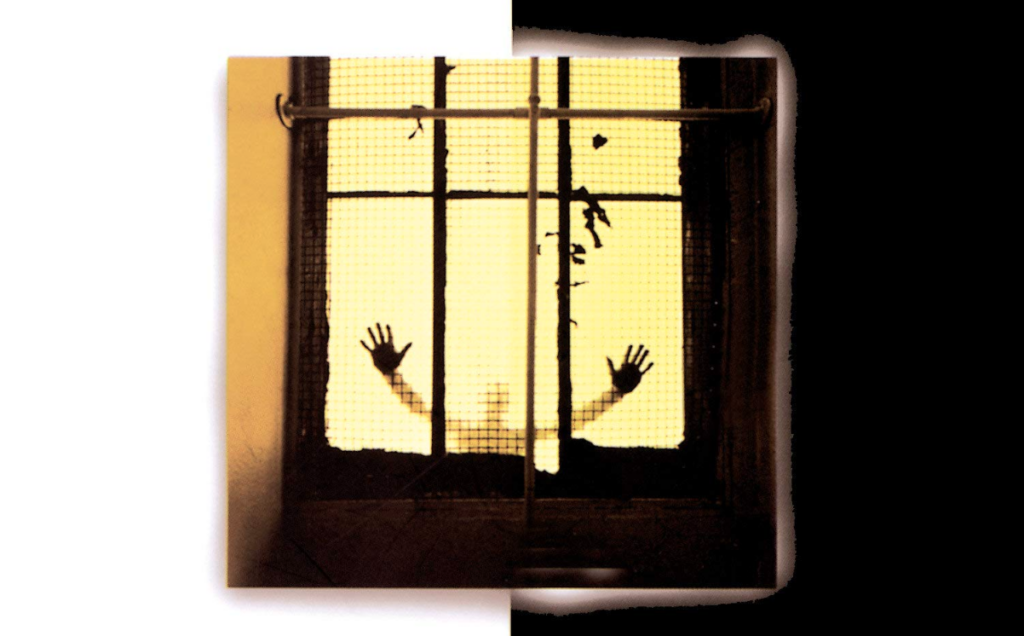

In 1995, a white woman named Susan Smith drowned her two young sons in a South Carolina lake and then covered up the crime by fabricating a story of kidnapping by a black man. This imaginary carjacker narrates most of the first cycle of poems in Eady's latest collection. In "Where Am I?" the narrator meditates on his own functional fictionality in perpetrating racial mistrust in a divided land: "I flicker from TV to TV … / I hover / Over so many lawns, so many cups of coffee. // I pour from lip to lip." Abstractly dispersed across the white field of vision, "a shadow on the water glass, / Changing hues, / The slant of my nose and eyes. Depending on the light / And the question," young black men are typecast as menaces to society, to be hauled out periodically for a symbolic and cosmetic justice. They remain the shadow on America's brightly lit sidewalks, predetermined by the "brutal imagination" for lives of violence and failure. This theme also animates the book's second cycle of poems, "Running Man," which were used in Eady's libretto for Diedre Murray's 1999 Pulitzer Prize-nominated jazz opera of the same name. Examining the violent death of a black youth and its effect on his family, these powerful poems also focus on the crushing weight of expectation, its uneasy converse with reality. Defying the role usually allotted to his kind, Tommy (the running man) shows intellectual promise, ambition, and sensitivity at an early age, "proof that maybe not everything happens / The way they say it should." But in the end, he is still dragged down by that heavy burden—unable to run quite fast enough. Still, words can hold the weight aloft long enough to speak painful, necessary truths. Blending vernacular cadence with a mournful lyricism, Eady sings the ongoing hurt of the African-American experience.

—Jonathan Cook

The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain

Han Shan (translated by Red Pine)

Copper Canyon Press, $17 (paper)

Han Shan (translated by Red Pine)

Copper Canyon Press, $17 (paper)

For Red Pine (the pen name of Bill Porter) and a host of scholars and writers, from John Blofeld to Jack Kerouac, the ninth-century Taoist/Buddhist poet who called himself Han-shan (Cold Mountain, after the cave he chose for his home) is one of China's greatest poets. This bilingual edition is a significant revision and expansion of Red Pine's 1983 collection of Cold Mountain's songs; in addition to John Blofield's helpful introduction (reprinted from the 1983 edition) and a new translator's preface, Red Pine presents here all of Cold Mountain's surviving poems, as well as poems by two of the poet's companions, Feng-kan (Big Stick) and Shih-te (Pickup). In its simplest expression, Blofield suggests in his introduction, "the Tao manifests the Tao…. Light and dark, up and down, health and sickness, life and death are all part of the interplay … for, since nothing came into being at my birth, nothing will cease to be when I die." Red Pine perceives, and translates, Cold Mountain's songs as unpretentious—yet profound—statements of identity with the Tao: "I reached Cold Mountain and all cares stopped / no idle thoughts remained in my head / nothing to do I write poems on rocks / and trust the current like an unmoored boat." Like the Tao itself, then, these thoughtful and peaceful songs simply exist. Nothing can be taken from them; nothing can be added to them: "Whoever has Cold Mountain's poems / is better off than those with sutras / write them up on your screen / and read them from time to time." Certainly the song (by Shih-te) that concludes this volume validates that sentiment: "Woods and springs make me smile / no kitchen smoke for miles / clouds rise up from rocky ridges / cascades tumble down / a gibbon's cry marks the Way / a tiger's roar transcends mankind / pine wind sighs so softly / birds discuss singsong / I walk the winding streams / and climb the peaks alone / sometimes I sit on a boulder / or lie and gaze at trailing vines / but when I see a distant town / all I hear is noise."

—Robert C. Jones

Smashing the Piano

John Montague

Wake Forest University Press, $19.95 (cloth), $10.95 (paper)

John Montague

Wake Forest University Press, $19.95 (cloth), $10.95 (paper)

"The Family Piano," whose repeated line "My cousin is smashing the piano" lends John Montague's new collection its title, gleefully celebrates the destruction of that eminent instrument—"a jumble, jangle of eighty-eight keys / and chords"—and suggests that this book will evidence a turn from the known, well-tuned melodics showcased in Montague's Collected Poems (1995). But this is a septuagenarian's book, and in it Montague, whose favorite mode has always been that of return—to lost loves and to the lost heritage of his (nearly) native Ireland—looks back through the tinted lenses of one who "always knew the atom could be broken." The "dark rooms" of Smashing the Piano are littered with the twisted rubble of the past, viewed by various incarnations of the speaker's past self—the child facing revelations of adulthood, the stages of parenthood, the broken-hearted lover, the perhaps even more broken-hearted man remembering those who are now gone. Against these odds, facing down despair, Montague offers the small and transcendent: "We always knew the atom could be broken / but nothing perishes." The nothings on display here: the bird whose broken body is once more flight-worthy, the cricket singing in the night, the "gilt casket" of a lover's head, the stars, the tiny sudden flower, "the self / listening to the self." Well-worn Romantic figures all, and it is a tribute to Montague's lyric power that each feels momentary and unique, a true stay against the personal and political hardships Montague lightly calls "botheration." Still, the power of these consolations is diminished by their being isolated, "free of earthbound history," and the poems in this collection that stick are those taken "from the Irish." Their rollicking rhythms and frank sexual joy present translation as an alternate mode of remembrance, materially rooted in the past, that follows the directive of Montague's Yeats: "Rejoice!"

—Jennifer Ludwig

A Paradise of Poets

Jerome Rothenberg

New Directions, $14.95 (paper)

Jerome Rothenberg

New Directions, $14.95 (paper)

In the early 1970s, Jerome Rothenberg read poems accompanied by a folk singer and klezmer band, a taped sound collage, clips from the Chaplin short "The Immigrant," and slides of old photos. To say his new work seems somewhat diminished on the page, then, does not necessarily imply criticism in the usual sense. His latest volume, A Paradise of Poets, still manages to blur traditional lines between literacy and orality, the "strong" author and tribal collaborator. "At the Grave of Nakahara Chuya (1907–1937)" feels like what it describes—a ceremony for a young Japanese Dadaist, whom the poem literally conjures from the dead: "& the boy who sang / & wore a round hat / fell into a broken sleep / & came out of his grave / & sat with us / & sang in a broken sleep." Rothenberg says the "gang of poets" in attendance tried on such a hat, a replica of one worn by the deceased. His admiration ennobles the poem and prevents it from being the odd, macabre piece it easily could have been. Rothenberg visually restores the poet in "The Leonardo Project," a set of twelve "poem-panels" which to philistines may seem more akin to the work of an office temp set loose on a photocopier. The language occasionally disappoints, which leads one to question David Antin's assertion that Rothenberg is "an American Celan." The lines "a place for noble death / for fish death" risk sounding bathetic, especially when the second line is later repeated. And what is particularly illuminating about "Death is always sudden, always comes after the fatal blow"? Overall, though, Rothenberg's project is highly engaging, and his final translations of Lorca and Picasso seem more culmination than appendix. Elsewhere the author honors Jackson Mac Low "who baffled me at first & from whom I later learned the farthest possibilities of form & meaning," and readers might judge Rothenberg equally guilty/worthy of this tribute.

—Brett Foster

A Fly in the Soup: Memoirs

Charles Simic

University of Michigan Press, $29.95 (cloth)

For Sigmund Freud, childhood was a paradox in that one's identity emerges at the very time when one's morals and emotions are shapeless. This paradox can present something of a conundrum for a biographer or memoir writer. Is childhood a convenient alibi for all sorts of adult behavior? Or is it an opportunity to speculate about the formation of moral judgements? For the poet Charles Simic, these questions are so much twaddle. His memoir A Fly In the Soupis a story of hazards, beginning with Simic's childhood in wartime Belgrade and his family's escape from Communist Yugoslavia, and running through his early adulthood in New York City and his induction into the US Army. The young Simic is bullied by politics; the memoirist, however, refuses to bully that younger self into a portrait of the child holding the secrets to the man. (His publisher doesn't resist the temptation, labeling the book a "coming of age" story.) If Simic is faithful to any experience from his early years, it's the sheer anarchy and uncertainty of existence—of being "a fly in the soup." Assembled from pieces that previously appeared in magazines and other books over the course of many years, Simic's memoir has a style and tone that modulates, sometimes wildly, from chapter to chapter. A narrative thread holds the story together, but it's the most distressed of lines, one knotted with anecdotes, frayed by rants, and tangled in meditations on poetry and life.

—John Palattella

The Other Lover

Bruce Smith

University of Chicago Press, $13 (paper)

Bruce Smith

University of Chicago Press, $13 (paper)

For centuries, poets have committed all manner of error in writing poems that aspire "towards the condition of music." In this, Smith's fourth volume of poems, we are reminded that verse can, in fact, capture the life and manic melody of jazz, at least within a certain limit. Smith's rhymed, unmetered stanzas quaver on the edge of rhythm and spontaneity as few other poets writing today could manage: "A ghost slur, a quaver / and stop. From the most meager // scraps of voice on the telephone—/ a half tone or quarter tone." His lyrics spin clever twists on conventional subjects, generally with great success; his mood indigos on death of lovers, death of anger, near-death of his father, and the death of loving and teaching literature renew poetic themes that have grown old only because they are important. Sometimes, however, the language suffers for lack of musical accompaniment; poetry is much more naked on the page than lyrics sung on stage, thus such cant as "We love each other now / as we loved each other then: / always and seldom. What's changed is the how / and the why and the when." His "Catullan" retains the jazz rhythm motif, but couples it with the jazz's ancient Roman equivalent (Catullus wrote raunchy, bitter poems excoriating love, etc.) and the result is one of the best, albeit uneven, poems I've read this year: "Hippolyta, you could be black-eyed / and fat in your seventh month / with you-don't-know-whose kid / and begging for bus fare." His take on Edna St. Vincent Millay is also accomplished, while his "dialogue" on Hart Crane approaches the unreadable as it imitates two voices interweaving. Only here does Smith conflate the hyper interplay of instruments in jazz music—an art of dexterity and precision—with mere, self-negating chaos.

—James Matthew Wilson

The Cherokee Lottery

William Jay Smith

Curbstone Press, $13.95 (paper)

William Jay Smith

Curbstone Press, $13.95 (paper)

The discovery of gold in 1828 on Cherokee land in northern Georgia, and the subsequent passage of the Removal Act, forced the relocation of 18,000 Cherokees—along with other Southern tribes, including Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, and Seminoles—to Oklahoma territory. William Jay Smith, part Choctaw himself, re-creates in this remarkable series of poems that tragic odyssey now known as "The Trail of Tears." Two poems ("Journey to the Interior" and "The Eagle Warrior: An Invocation") introduce the sequence, followed by an evocative vision of "The Cherokee Lottery," the "clumsy wooden wheel / … poised above great black / numbers painted on bright squares… / to designate the farms / that now were up for grabs." Later poems in the sequence give us vivid images—way stations along the trail—of what has been called "a blot on American history": In "The Buzzard Man," an old Choctaw on the trail recalls the ceremonies of "the old days" that were performed "when a Choctaw died," and laments: "Now as they march us / to the west, / we abandon our dead / along the way—/ …and only our tears / to seal our trail"; "The Song of the Dispossessed" accuses: "You sent us to this desert, / this sand, these pitted stones … / where now above this barren earth / your great bald eagle screams, / that robbed us of our country / and carried off our dreams." The last poem of the sequence, "Full Circle: The Connecticut Casino" (dated 21 January 2000) sardonically celebrates the "glory" of the Foxwoods Resort Casino of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nations, presided over by "the giant bright-colored mask of Coyote, / or, rather, of Ms. Coyote, / (the trickster, consummate cross-dresser …)," one ear "supporting a freshly-picked white rose, / the other dangling slightly, tipped by its earring, / a bright-beaded tassel / that looks for all the world like an Indian price tag." —Robert C. Jones

Trilce

César Vallejo

César Vallejo

Translated by Clayton Eshleman

Wesleyan University, $19.95 (paper)

Wesleyan University, $19.95 (paper)

This re-issued, bilingual edition of poet, editor, and translator Clayton Eshleman's 1992 version of Vallejo's Trilce reminds us not only why we read the seminal Peruvian poet, but also the real value of meticulous translation. Those behind this rendering of the 1922 masterpiece—including Eshleman, a longtime Vallejo scholar; Americo Ferrari, author of the book's introduction and professor of Translation Methodology at Geneva University; and Julio Ortega, the establisher of the Spanish text and a professor of Hispanic Studies at Brown—offer a model of uncommon scrupulousness. Their painstaking efforts (they spend several pages describing a "four-pronged" revision approach) might seem almost comically fastidious were their results not so stunning: we are rewarded with crystalline verse. Ferrari's posit that Trilce "expresses an unheard-of emotion" is on the mark; Vallejo is often more yearning than Neruda, at times displaying as much "sensitive individualism and … aesthetic aristocra[cy]" (H. R. Hays) as Carrera Andrade. He blends sexual, luscious music ("I think about your sex, / before the ripe daughterloin of day. / I touch the bud of joy, it is in season"), a Parra-like anti-poet self ("Murmured in anxiety, my suit / long with feeling, I cross the Mondays / of truth. / No one looks for me or recognizes me, / and even I have forgotten / whose I will be") and revolutionary impulses ("Refuse, all of you, to set foot / on the double security of Harmony. / Truly refuse symmetry"); he is at once a captive and consumer of an alternately bleak and sumptuous plane. Yes, Trilce was written in the throes of Modernism, and the poems owe debts to his short prison stay and travels to cosmopolitan Lima and Paris—but it's a book that transcends any mode or moment. Fear and sensation are Vallejo's guides, the "dirty honeycombs in the open air of little / faith." It is an air we all breathe, one uniquely rarefied by Vallejo's humble, virile voice.

—Ethan Paquin