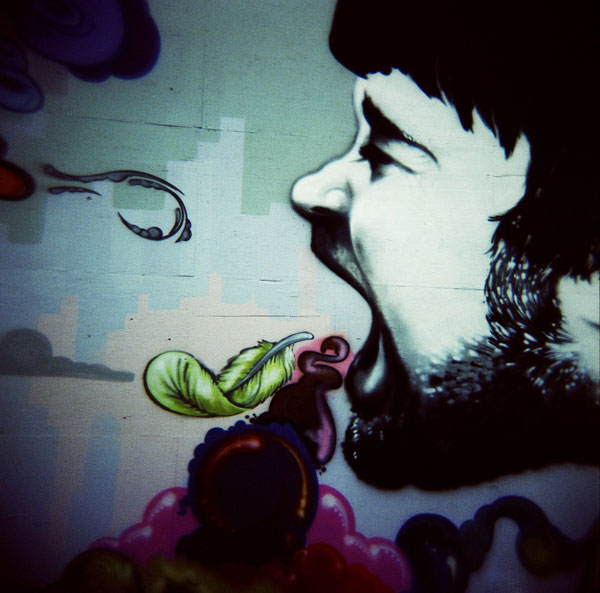

Photograph: Maika Keuben

The Book of Interfering Bodies

Daniel Borzutzky

Nightboat, $15.95 (paper)

The Warmth of the Taxidermied Animal

Tytti Heikkinen, translated by Niina Pollari

Action Books, $16 (paper)

Complicity

Adam Sol

McClelland and Stewart, $18.95 (paper)

If you write a book of poetry about sharks, you might get attention from readers who care about sharks. If you write a book of poetry that is explicitly and consistently about poetry—its institutions and conventions, how we decide what counts as poetry, what we expect it to do—you might get extra attention from readers who care about poetry, which is to say from anyone likely to pick up new poetry at all.

No wonder, then, that some poets take the institutions and the limits of contemporary poetry as their explicit subjects. Attention to such things connects Conceptualism and Flarf, the two most hyped U.S. movements of the last ten years, to each other and to the historical avant-garde. But there are other ways to address conventions of present-day poetry and to make poems explicitly about them. It is a good decade for such poems—take Amy Newman’s much-noticed Dear Editor (2011), Guy Bennett’s Self-Evident Poems (2011), or Peter Davis’s underrated and very funny Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! (2010). In “Poem Addressing My Intentions in This Poem and How I Feel Like I’m Doing,” Davis writes, “It is important to me when considering this poem to do something that’s easy, something that doesn’t take much time or energy. I say that because this isn’t the only poem I need to write. I need to write others too, to increase the possibility of publishing something. On the other hand, it’s also important to me that it contains a great truth.” Davis is also the author of “Poem Addressing People With Certain Expectations About Poetry That Are Not Fulfilled in This Poem”; the rest of the poem reads, “Change.” It’s a joke about Rilke too.

While these authors appear to take poetry as their subject almost to the exclusion of anything else, other equally self-conscious poets keep different goals in view. Daniel Borzutzky is probably best known for his translations of the Chilean poet Raúl Zurita, but his own recent book takes up kinds of poetry that try to represent, or to utter, great truth about terror, state torture, global inequity, and public violence. The Finnish poet Tytti Heikkinen uses her unruly characters to ask how poetry can speak to, or about, or for, people who seem inarticulate, unable to “express themselves.” Adam Sol takes the narrower field of North American lyric, its clichés and its history, and manages both a sheepishly funny series of attacks and a measured apology for poetry as such. Together the books show how poems about poems about poems can put up a corrosive critique of poetry as we already know it and how they can mount a considerate defense.

“I see thousands of bone shards and blood and bits of hair and in each fragment there are villages, towns, hamlets, inlets, streets, suburbs, cities, states and countries,” Borzutzky’s opening poem declares. Much of his book asks how, and whether, he can make poems from such visions. Many of his poems’ titles (“The Book of Forgotten Bodies,” “The Book of Non-Writing”) describe books that don’t exist: “Each page of the Book of Flesh dissolves as it is turned, and new flesh pages take their place.” Often he attacks, with a vehemence that strongly suggests he shares them, the dreams of political efficacy that other radical poets have maintained: “A poet I know wishes Al Qaeda would bomb the building of a poet he does not like. . . . The miniscule hermaphrodite poet on my window is a terrorist whose deepest desire is to turn Manhattan into a giant bowl of milk.” (Borzutzky is mocking a fantasy of phallic power; actual intersex or genderqueer poets need not apply.)

It is tempting to say that Borzutzky writes about not being Zurita: not being, and not wanting to be, a poet whose massive answers to historical suffering reorient a national tradition, yet remaining aware of the suffering that other poets address. Borzutzky also mocks—or does he confirm?—the idea that information exchange, the circulation of words, what Michel Foucault called power-knowledge, is just another form of violence: “The poet was hired to teach poetry to children but the children left his courses thinking that poetry was something to slice people open with and when they heard iambic pentameter they fled into corners and howled.” His acoustic forms, or anti-forms—arrhythmic single-line stanzas, prose blocks—fit his doubts: “This poem is rhythmically unappealing. // The form of this poem has little to do with its content. // This poem longs to be doused in gasoline and shoved into the mouths of enemy combatants at Guantanamo Bay.”

There is something self-righteous, something having-it-both-ways, about Borzutzky’s repeated insistence that his poems do and do not address states of emergency, victims of torture: “Let us describe our readers. Their fingers have been pulled off by doctors who specialize in removing the fingers from the residents of dead nations. . . . Some of the readers have lost their tongues and those tongues are also in books.” There is something self-righteous, too, something hairshirt-ish, about Borzutzky’s repeated implication that his poetry, unlike other poetry, acknowledges the privilege that went into writing it: “Budget Cuts Prevent Me From Writing Poetry,” one title reads. Some of his pages are not much more than extended riffs on Walter Benjamin’s quip that every document of civilization also documents barbarism. (Benjamin, with Marguerite Duras, pops up in epigraphs.)

But both ways might be the only way we now want it. Some people in Borzutzky’s audience, like many people in Zurita’s, have seen state horrors firsthand. But most of us in the United States have not, and our guilty fascination with poets who have is one of Borzutzky’s subjects. Another is the wish—common among oppositional or countercultural writers, from Jack Spicer to Amiri Baraka (“Poems are bullshit unless they are trees or teeth . . . dagger poems in the slimy bellies / of the owner-jews”)—that poems be

If poetry cannot close our prisons or raise our war dead, at least it can give us someone to talk to.

overtly powerful, tangible things. We may want poetry to do what it cannot do, to perform a magic in which we no longer believe or a political efficacy that no longer makes sense. And so in Borzutzky’s poems we are brought up short and discover that poetry is the despised Other of more consequential textual forms such as the PowerPoint slideshow: “Power needs only power to justify itself, reads the next slide in the Power Point presentation, which is the next line of the poem.”

If we cannot tell what Borzutzky wants us to do, we can say how he realizes his striking tone: a dry anger, a disillusioned slow burn, that addresses both the American “poetry of witness” and the great projects of Latin moderns, from Vallejo to Vicuña, at one anxious and alienated remove. The opposite of poetry, for Borzutzky, is not prose but nonlinguistic power, as in torture. Or maybe its opposite is official prose, which reduces people to statistics or aids in their literal confinement. Or maybe the opposite of true poetry, poetry that does justice to our disastrously unjust world, is namby-pamby verse about first-world problems. Borzutzky maintains a magnificently irritable dialogue with that sort of poetry too. Consider a poem whose title is a cliché, “Poetry Is Dangerous in America”: “I was tired of practice. I wanted theory,” it says. “So I thought about, but did not act upon, ways I could go beyond social critique and offer an alternative entry into the present tense, whose gates were blocked by poets who thought terrorism and lyricism were interchangeable. I gave up on the first person. . . . Suddenly I was old, and I had no one to fucking talk to.”

• • •

Tytti Heikkinen has someone to talk to, though we may not understand the conversation: she writes in Finnish, and wins major Finnish awards, but she comes to Americans, as Borzutsky’s translated Zurita comes to Americans, through the astonishing energies of Action Books. The press specializes in translated poetry and in a poetry of “anti-poetic” extremes, in what the editors’ manifesto calls “unknowable dys-contemporary discontinuous occultly continuous anachronistic avant-gardes.” Action authors are united in their commitment to shock, but, as you might expect from a globe-spanning catalog, they vary widely in what else they do: Heikkinen, in English translation by the Brooklyn poet Niina Pollari, stands out for the chirpy, sloppy, rude, fresh excess with which she asks what poetry ought to do— and for the old, or Romantic, answers she finds.

“As long as consciousness exists,” Heikkinen writes, “reality will be abused. Our task is to ensure that meeting it will be painful, and that the pain will continue until the person experiencing it feels ill.” It is a very Action Books thing to say. She wants, like Antonin Artaud or Genesis P-Orridge, an art that makes us queasy: an art that refuses what poetry “ought to do.” In her poem “Close call—feelings about aesthetics,” the rules of taste and form fare no better than the rules that governed “Soviet-era tenements”: the supposed freedom of the aesthetic realm is nothing but “freedom to accept institutions that define / these laws,” by which “the past always forces / the future to fall.” Heikkinen and the characters she creates want to keep those laws off their bodies: “My brains melt / my brains melt / and two suited men arrive at the coat check. . . . Brains just escape far away, / yep, yep.”

Like the Flarfists, as Pollari notes, Heikkinen can derive poems from Internet searches, transforming “bloggy Google sludge.” Her results sometimes recall fetish porn: “Mika got up then bent over so his tool was right in Katja’s face. Katja opened her thighs, the simplest form of the desire for prizes. Warm liquid flowed from the slit.” Even the non-smutty pages can induce squirming. Heikkinen conceives modern life and its weird oppressions not as complicities with the wartime state but as forms of mandatory sociability, mandatory sexuality: language itself is like “a stripper pen. / When you tilt it, the swimsuit slides away from the woman and reveals the body. / The picture is endless but placid, presents an argument / with a blackbird voice.” Heikkinen will use her poetry not to sing, not to argue cleanly, not to reveal any conventional beauty, but to do something else.

In fact, she will use it to become someone else. The last and best third of Heikkinen’s book holds poems in the voice of her character Fatty XL (in Finnish, “Läski XL”). They sound like drunk tweets from someone who can barely read:

Gonna say one thing just as soon as

this vomiting

stops. . . .

Went shopping today for cute shoes. !!

Everybody is

gross but me and my friends.

The alienation from bourgeois society that Romantic poetry once promised, the alienation from artistic tradition that the historical avant-garde could give, becomes for Fatty XL the distance from “civilization,” from any aesthetic norms, associated with an undisciplined, out-of-shape, “unattractive” female body, and with undisciplined language, illiteracy: “Fuck I’m a fatty when others are skinny. / Also Im short, am I a fatty or short? Wellyeah . . . . Now I’m / puttin distance btwn me and everything, because I’ve been so / disapointed in my self.” If you do not think that string of misspellings has anything in common with the goals of canonical lyric poetry, perhaps you need to reread “Tintern Abbey,” especially lines sixty-four through seventy-four.

But Fatty’s reflections don’t sound like anything that has been presented, at least in English, as poetry, though Kathy Acker’s texts comes close: they are meta-poetry, a series of attempts to hack away at the limits of what poetry can do, what kinds of consciousness it represents. Yet Fatty XL is less modern, more Romantic, than she seems. You can get used to her diction, her emoticons (“<3”), just as you can get used to Jamaican patois or to Scots, and when you do you might be moved:

I’ve been told that no dude is

interested in me. I don’t know a lot

about sex or

conversation,cause nobody has

actually ever explained

them to Me, I have alone had to try to

find them in books.

Have to laugh. .Am I stupid cause I

don’t get generally what’s going on

and scramble ‘subjects’ and

‘objects’ and who gave what to whom

and when?

Samuel Taylor Coleridge also complained, in “Dejection: An Ode,” that he could not find love in real life, could not always tell subjects from objects, and had to rely too much on books. Coleridge hoped to numb himself, partly through scholarship: he planned “not to think of what I needs must feel,” and “by abstruse research to steal / From my own nature all the natural man.” Fatty XL has a plan, too; she

took

a pain pill. And, stuff started working

RIGHT away with a couple

beers, and since then not even a piece

of pain

in my head!.

You really get used to pain when you

can’t feel

anything. What song is playing? No

song at all.

Her language is anything but melodic; it is un-song-like. And yet it says what lyric poetry is supposed to say: it objects to the bad fit between the self and the world, between emotion and available language, between what we feel that we want and what we believe that other people can get. These poems, so dependent on uncouth and shocking surfaces, end up more Romantic than those surfaces suggest, and in doing so they either condemn Fatty’s Romantic goals (to find a figure for loneliness, to give language to her complaint) or suggest that even Heikkinen shares them.

Heikkinen’s discombobulated meta-poems or anti-poems pivot from the nihilistic to the frivolous, from the philosophical to the emetic, inside a sentence. Read in English, they sum up, as much as any Action book has, an aesthetic founded in translation, in poetry that sounds “wrong,” discomfiting, unsmooth, that sounds like it doesn’t belong in the language we speak. Borzutzky, too, has said that he tries to copy, in his poems, the jars and knocks of translation: “I sometimes try to interrupt my own writing so that the process of translating myself doesn’t go so smoothly, so that I make my own writing sound as if it is not able to fully communicate what it was intended to say.” And yet, for all the bizarre effects of self-reference and out-of-bounds diction both authors provide, the answers to their questions about the purpose of poetry can be quite traditional: Fatty XL, too, wants someone to translate her, someone to talk to. You, reader, are she.

• • •

If poetry in American English cannot close our for-profit prisons or raise our war dead, at least it can give us someone to fucking talk to. Its incapacities, and our frustrations, are some of the things it lets us talk about. And poems-about-poetry, poems that take our frustrations over poetry-in-general as their subject, do not come only from polyglot post-avant-gardes. The Indiana-educated, Toronto-based Adam Sol entitles his new—and determinedly accessible—book Complicity. Like Borzutsky and Heikkinen, he asks what, and how much, the familiar forms of poetry can give.

“For one day I will not be ironic about the power of art,” Sol’s volume begins. “For one day I will try not to be ironic about the power of art.” That poem compares poetry to Pluto, now demoted to “dwarf planet”; “art has been declared a dwarf pursuit.” Whatsoever dwarf pursuit thy hand findeth, pursue it with all thy might; for there is no work, no art, nor knowledge, nor even irony, in the grave. That is the meta-text for Sol’s meta-poems, never offered more endearingly than in his “Sestina in B-flat for the Glockenspiel,” in which a school band geek gets ready to practice. Her classmates

have such sure hands,

she thinks, and she can hear the

sounds

they make, the laughter in the practise

rooms that make her feel like a little

girl.

She is a “late bloomer,” and like the

glockenspiel,

she is awkward at the games they play.Only it isn’t really play,

is it? it’s life.

Contemporary poetry, like glockenspiel (the instrument’s name means “bell-play”) practice, like sestina form, like high school social life, like life itself, goes around and around, might be derided as a mere game, and doesn’t accomplish much outside its own specialized field of interest. That is not a reason why poetry does not matter, but a precondition for how it does.

And yet we may wish it could matter differently; we may wish that poetry could engage more of the world. Sol’s poem “Engagement” puns on an engagement that leads to marriage, engagé writing that leads to political change, and soldiers told to engage the enemy: “The clear typeface and perfect binding are misleading. / The reader is uncomfortably and inappropriately implicated. . . . The young men, necks dirty and damp, advance.” Sol’s poems-about-poetry also incorporate kinds of non-poetic writing. “Note Found in a Copy of A Midsummer Night’s Dream” compares its folded prose to Shakespeare’s play; “Bryan, / I did want to do / what we did last night! . . . I did not do anything that I did not want to do!” What work of art could mean—or reveal, or disturb us—as much as that?

Almost any work of art can, but perhaps not so immediately, so rawly. Robert Lowell once distinguished between two American poetries, the raw and the cooked, but all poetry can seem cooked—and perhaps too well done—beside raw data on matters of public concern, raw testimony of victims, or even the raw weirdness of teenage diaries. Even Heikkinen’s sexts and texts are figuration: there is no such person as Fatty XL. And yet if you turn away from the horrific, or the porny, or the raw, from the aggressively contemporary and the overtly weird—if you rely, for attention, on moves we already recognize as poetry—not only might you get ignored, or feel uncool; you might also feel stuck inside rigid, old forms. Poets, for Sol, can thus resemble cicadas—no sooner do we shed our old forms than we grow, live inside, and feel confined by, our new ones:

It’s hard to invent a personality

that doesn’t make me feel like an ass.

But soon this will pass.

My exoskeleton will harden

and I’ll resume with the jargon

that reflects my complicity.Until then, play me the ukulele

version of “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

Are those the real words, or are they

just fantasy?

Search me.

Elsewhere Sol addresses, mocks, imitates, writers of a post-Bishop, post-Lowell mainstream whose conventions go back at least to “Tintern Abbey”:

Here I am at the specific location,

with its world-inflected familiarity,

and its overlooked, unlikely beauty. It

is here

where, after a brief meditation on an

esoteric topic,

I will come to a realization at once

profound

and elementary, something we all

know

that had never before achieved itself

in song.

You can dismiss such effects as all-too-light comedy (cf. Billy Collins), but if you do that, you will be missing out on one of the kinds of entertainment, as well as one of the kinds of self-questioning, that poetry, according to Sol, is suited to perform. If you are a reflective, wry, and unaggressive poet such as Sol, your mission is not to attack this kind of experience, which after all could encompass much human life (we go places, we remember stuff, we see things), but to describe it so that your version feels new. And if you want to dismiss it as mere craft, mere language, consider what happens to us when language fails, as in Sol’s poem about debility in old age:

A nearly blank calendar

on the nightstand.

No appointments in April.

May 4: Throat

Test. May 5: Pay ConEd.

May 6: Dr.

Dandi refer to OncGastro.

May 15: Philharmonic,

in pencil, crossed out in pen.

This figure will not see the philharmonic again.

When we face not the news, nor the PowerPoint, nor the Internet, but the silent void, poetry—defined as figuration, or as form—may not do much, but it is better than nothing, and without it, nothing is what we face. The void is “What only poetry can confront. / Not adequately, but closer to it / than anything else at our disposal.” Those lines come from Sol’s “Poem for Noah Pozner,” a halting thing dedicated to the youngest victim in the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown. It is not the best poem in Sol’s book—that would be “Template Poem,” or perhaps the sestina, or the poem called “Check Authenticity Here”—but it tells us why books of poetry, even books as carefully not-quite-innovative, as “accessible,” as craft-oriented as Sol’s, keep being written, and why some of us still want to read them.