Wake Forest, $12.95 (paper)

Poems 1968-1998

Paul Muldoon

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $19 (paper)

Collected Poems 1952-2000

Richard Murphy

Wake Forest, $18.95 (paper)

James Joyce is reported to have said that he wrote Finnegans Wake, his linguistically dense and elusively allusive narrative of the nocturnal mind, "To keep the critics busy for three hundred years." Northern Irish poet Paul Muldoon seems to aspire to a comparable measure of critical notice, or notoriety. Certainly the proliferation of scholarly exegeses of his poems—reviews, articles, and at least two recent full-length books—testifies to the fascination Muldoon's work holds for an academic readership engaged by far-reaching intertextuality, radically subversive formal ploys, riddles, puns and other verbal conundrums, private jokes, and even the odd red herring: in short, by the full range of deconstructive (often implosive) stylistic devices and extravagances available to a poet.

At its most extravagant, in the nearly book-length Madoc: A Mystery,Muldoon's pursuit of a poetic extreme may even appeal primarily to the perfect audience that Joyce imagined for his "lingerous longerous book of the dark": "that ideal reader suffering from an ideal insomnia." Part history, part parable, part connect-the-dots catalogue of Western philosophy, Madoc—which tells the tale of what might have been if British poets Southey, Coleridge, and Co. had followed through on their plan to establish a "pantisocracy" in America—may also be in largest part an elaborate spoof: as much Muldoonery as provocatively enduring poetry. In fact, when first published in 1990, Madoc seemed to represent not only the inevitable outcome of Muldoon's distinctive poetic evolution (his tendency toward both longer forms and increasingly arcane points of reference), but also a daunting prospect of further verbal and formal chicanery.

In the context of Muldoon's accumulated body of poetry, however, the epically ambitious Madoc appears to be a conspicuous departure from the poet's usual precincts. For by other reliable indicators, Muldoon is a lyric poet at heart, and the work gathered in Poems 1968–1998 reveals a writer who, even while straining against the formal and stylistic conventions of traditional lyric poetry, still relies on those conventions to locate himself geographically, politically, socially, and artistically. Indeed, even while bedazzling his readers with an endless array of self-concealing devices—metaphorical masks and trick mirrors as well as all manner of diverting verbal sleight of hand—Muldoon explores essentially conventional thematic territory: innocence and experience, familial relations, amorous and domestic relations, place and politics, and the art of poetry itself.

In a relatively early poem, Muldoon says that "all the fun's in how you say a thing." And for his readers, a goodly measure of the pleasure of engaging with Muldoon comes from watching him have fun turning over such familiar terrain—or overturning it. From the outset, Muldoon's vision has had a subversive edge to it. In "Blowing Eggs" (from New Weather [1973]), Muldoon recounts a boy's experience of robbing a bird's nest, and concludes with the image of "his wrists, surprised and stained" by yolk and albumen. Though the poem suggests Seamus Heaney's famous "Death of a Naturalist," in Muldoon's hands the desecration carries no regret-filled revelation ("I sickened, turned, and ran," Heaney writes, lamenting the loss of innocence). Rather, for Muldoon, "This is the start of the underhand"—a foreshadowing of his ultimate trademarks: writing that it more piquant than poignant, and that revels in how experience scoffs at innocence.

Of course, Muldoon is capable of writing poignantly. "Incantata," for example, comprises forty-five closed stanzas elegantly slant-rhymedaabbcddc, and compares favorably with the loftiest work of W. B. Yeats (a true master of the eight-line stanza) in dignifying the life and the death of a former partner, American-born graphic artist Mary Farl Powers. But a more typical take on a passionate relationship might be "Something of a Departure," whose double entendres clearly owe a debt to that feature of Irish-language poetry that Heaney has called "verbal philandering":

Your thigh, your breast,

Your wrist, the ankle

That might yet sprout a wing—

You're altogether as slim

As the chance of our meeting again.So put your best foot forward

And steady, steady on.

Show me the plum-coloured beauty spot

Just below your right buttock,

And take it like a man.

As he acknowledges with a nudge and a wink in "Kissing and Telling" ("I could name names. I could be indiscreet"), Muldoon enjoys the telling at least as much as the kissing.

Ultimately, such self-satisfaction in the making of poems takes on a political dimension as well. Evidently subscribing to the words he puts into the mouth of W. H. Auden—"For history's a twisted root / with art its small, translucent fruit // and never the other way around"—Muldoon rarely engages directly with the "Troubles" of contemporary Northern Ireland. In fact, even the title poem of his volume Meeting the British (1987) foils expectations by focusing on the colonized status not of his own Ulster Catholic (and predominantly nationalist) tribe but of Native Americans, as they encountered the army of General Jeffrey Amherst and Colonel Henry Bouquet in 1763: "They gave us six fishhooks / and two blankets embroidered with smallpox." Instead, appropriating that more-British-than-the-British fixed form, Muldoon writes sonnets, or brilliantly irreverent sonnet variants: including no fewer than 150 fourteen-liners of one shape or another, Poems 1968–1998 affords emphatic affirmation of Heaney's defiant claim from the mid-1970s that "Ulster was British, but with no rights on / the English lyric."

• • •

Surely by no coincidence, the sonnet also appeals irresistibly to another Northern Irish poet of Catholic nationalist stock, Belfast-born Ciaran Carson. His Selected Poems, which includes a generous sampling from his two impressive volumes of sonnets published in 1998 (one a series of inventive translations from the French masters of the form), suggests that Carson, no less than Muldoon, would elicit the approval of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote in 1839:

Rhyme.—Rhyme; not tinkling rhyme, but grand Pindaric strokes, as firm as the tread of a horse. Rhyme that vindicates itself as an art, the stroke of the bell of a cathedral. Rhyme which knocks at prose and dullness with the stroke of a cannon ball. Rhyme which builds out into Chaos and old night a splendid architecture to bridge the impassable, and call aloud on all the children of morning that the Creation is recommencing. I wish to write such rhymes as shall not suggest a restraint, but contrariwise the wildest freedom.

A native speaker of Irish (and thus a minority even within the minority Catholic community in Belfast), Carson indeed seems to feel liberated by the liberties he takes with what he refers to, not quite ingenuously, as his "Second Language": "I am like a postman on his walk, / Distributing strange messages and bills, and arbitrations with the world of talk."

Certainly, as his signature piece "Belfast Confetti" makes manifest, Carson's use of English has pronounced political implications: "Suddenly as the riot squad moved in, it was raining exclamation marks, / Nuts, bolts, nails, car-keys. A fount of broken type." In general, however, Carson appears far less interested in analyzing the sectarian politics of Northern Ireland than in proving poetry's capacity to capture something of the prevailing spirit of his troubled province as a literal "world of talk." Thus, while essentially a lyric poet, Carson—who has recently published a richly evocative memoir and two compelling novels—betrays a deeply ingrained impulse to tell stories. Not just cleverly verbal but subtly vernacular, the opening lines of "Dresden," for example, introduce not just a text but a textured record of a distinctive brand of squalor:

Horse Boyle was called Horse Boyle because of his brother Mule;

Though why Mule was called Mule is anybody's guess. I stayed there once,

Or rather, I nearly stayed there once. But that's another story.

At any rate they lived in this decrepit caravan, not two miles out of Carrick,

Encroached upon by baroque pyramids of empty baked bean tins, rusts

And ochres, hints of autumn merging into twilight. Horse believed

They were as good as a watchdog, and to tell you the truth

You couldn't go near the place without something falling over:

A minor avalanche would ensue—more like a shop bell, really….

Dissecting that squalor by way of an engagingly discursive account of Horse's place in his community and his experience as a tail gunner with the Royal Air Force during the bombardment of Dresden (renowned for its fine china), the narrative eventually focuses on Horse's pathetic preservation of a piece of a china milkmaid that he had accidentally broken as a child:

He lifted down a biscuit tin, and opened it.

It breathed an antique incense: things like pencils, snuff, tobacco.

His war medals. A broken rosary. And there, the milkmaid's creamy hand, the outstretched

Pitcher of milk, all that survived.

By making emblems out of the fragments that we desperately shore against our ruins, this poem typifies how Carson leads his readers on a marvelous (frequently marvel-filled) excursion into the very heart of his culture.

• • •

Born in 1948 and 1951, respectively, Carson and Muldoon have both managed to emerge from the shadow cast forward on a half-generation of Irish poets by Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney. With the publication of Collected Poems 1952-2000, Richard Murphy, born in 1927 and thus Heaney's senior by twelve years, likewise stakes a claim to readerly attention that he has not garnered consistently over a half-century career. Arriving on the literary scene a good decade before the development of Irish Studies (even as an academic cottage industry centered around Yeats and Joyce), Murphy seems also to have slipped between the cracks of the critical attention devoted either to the chorus of poetic voices responding to the Troubles in Northern Ireland—Heaney, John Montague, Derek Mahon, Michael Longley—or to the first generation of Irish women poets to command international recognition—Eavan Boland, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, and Medbh McGuckian.

At least some of Murphy's past-due attention should relate to his evincing a Yeats-like mastery over theme and poetic form as the way and the means for transforming personal experience into "the artifice of eternity." The precisely worded and meticulously phrased opening strophe of "Sailing to an Island," the title poem of his breakthrough second volume, epitomizes the authority of Murphy's poetic stance:

The boom above my knee lifts, and the boat

Drops, and the surge departs, departs, my cheek

Kissed and rejected, kissed, as the gaff sways

A tangent, cuts the infinite sky to red

Maps, and the mast draws eight and eight across

Measureless blue, the boatmen sing or sleep.

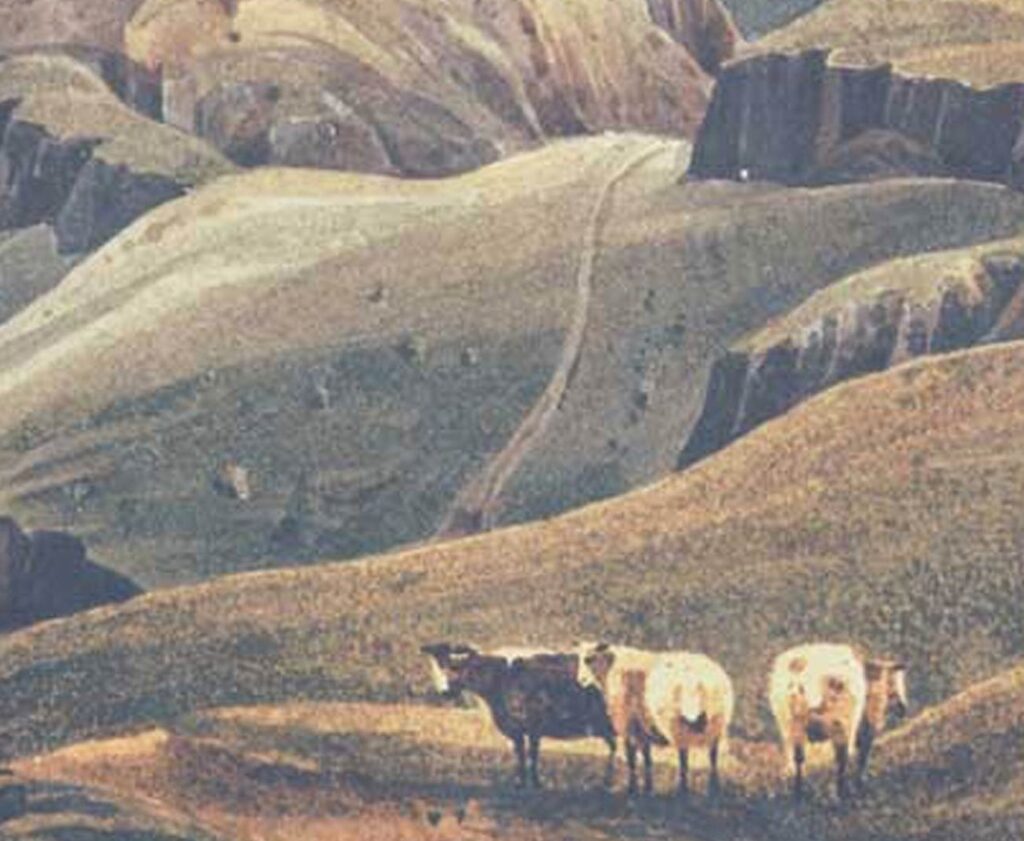

Born in County Mayo, Murphy turns and returns to the familiar world of the west of Ireland in poem after poem. But his work is informed too by a unique cosmopolitan temperament. Currently dividing his time between Dublin and Durban, South Africa, Murphy also spent five formative years in Ceylon, where his father was the last British Mayor of Colombo, and spent subsequent sojourns at boarding schools in Ireland and in England and as a scholarship student at Oxford (where he was tutored by C. S. Lewis).

Thus, while a detailed remembering of a childhood experience in Ceylon, a poem like "The Writing Lesson" reads readily as a parable of Murphy's lifelong grappling with both the daunting demands and the melodious possibilities of words:

"Run out and play." Appu's cooking curry for lunch.

He stands under a flowering temple tree

Looking up at a coppersmith perched on a branch:

Crimson feathers, pointed beard.

All day long it hammers at a single word.

Is it bored? Is it learning?

Why can't it make a sentence, or break into song?

Whether personal domestic lyrics, evocative sketches of return visits to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), a narrative recounting of the bloody Battle of Aughrim in 1691, or the fifty-sonnet sequence The Price of Stone—which charts the poet's life through an architectural catalogue of buildings modest and grand that he has lived in or visited—Murphy's poems register with a cumulative weight and density approaching the monolithic. The publication of his Collected Poems begins to give this poet long-deserved recognition.