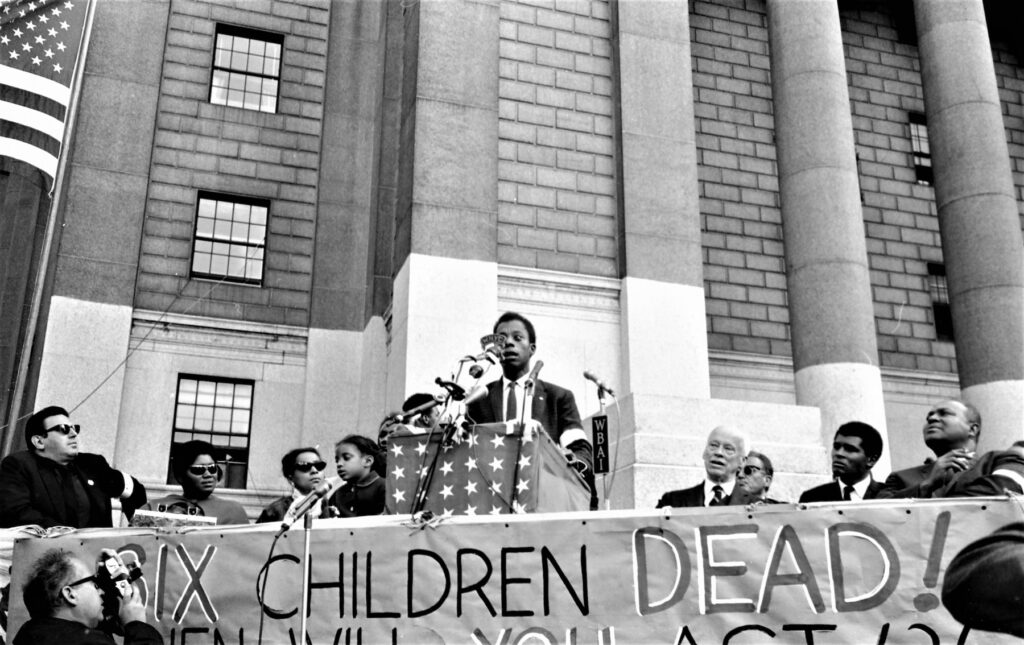

“Now we are here not only to mourn those children, who cannot really be mourned,” said James Baldwin in his address to a crowd of seven thousand that filled Foley Square in lower Manhattan on September 22, 1963. It was the Sunday following the Sunday morning bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, one of the most heinous hate crimes since the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board had sparked a modern Black protest movement—and with it, a resurgence of white backlash. Over the past year, the traditionally standoffish 16th Street Baptist congregation had increasingly engaged the freedom movement. During protests in April and May of that year the church served as a base from which thousands of marchers—many of them children—departed on their way to being intercepted and jailed by police. On the morning of Sunday, September 15, the inaugural Youth Day at the church, a small group of girls had stopped in the women’s lounge to attend to their hair and straighten each other’s outfits between sessions. At 10:22 a.m. a bomb hidden under the stairs the previous night by Klansmen blasted out the wall and stained-glass window of the lounge. Four girls, ages eleven to fourteen—Addie Mae Collins, Carole Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, and Carole Robertson—were killed in the explosion. Later that day, teenagers Johnny Robinson and Virgil Ware were fatally shot in separate racist attacks. In one day, six Black kids in Birmingham were dead.

The crowd to which Baldwin spoke had gathered as part of a “National Day of Mourning for the Children of Birmingham,” as had crowds in three dozen other cities across the country, from Seattle to Pasadena to Tucson, from Chicago to Shreveport, from Miami to Bridgeport. “We are here to begin to achieve the American Revolution,” Baldwin continued, warning that if organized mass action wasn’t taken, “this country will turn out to be in the position, let us say, of Spain, a country which is so tangled and so trapped and so immobilized by its interior dissension that it can’t do anything else.”

The week following the Birmingham bombing was also the week when Baldwin began a period of radicalization that would last through the decade and shape the rest of his life. His The Fire Next Time, published that January, had made him a sensation. Baldwin had built his reputation in works that brilliantly accommodated the cultural priorities of Cold War liberalism: complexity, ambiguity and interiority. In that vein, he penned passages such as those in his 1957 essay “Princes and Powers,” which covered the First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Paris for the Cold War propaganda outlet Encounter. There as elsewhere during those years, Baldwin stressed that it was “the lonely activity of the singular intelligence on which the cultural life—the moral life—of the West depends.” Cultural health, he held, requires an acceptance that “each man, in awful and brutal isolation, is for himself, to flower or perish.” In a shift that had been in the making for a few years, the fall of 1963 witnessed America’s newest and brightest literary celebrity speaking with determined clarity and certainty, imploring mutual and collective means of remaking ourselves and our world in ways no mere assemblage of individuals could even attempt.

So where for years it had been common to find Baldwin’s name in the table of contents of liberal magazines such as The Nation, Partisan Review, Commentary, and Harper’s accompanied by the likes of Kay Boyle, Lionel Trilling, Dwight MacDonald, Daniel Bell, and Nathan Glazer, on the National Day of Mourning Baldwin shared the microphone and the stage with radicals and activists representing at least two generations: longtime pacifist insurgent Bayard Rustin, who had served as Deputy Director of the March on Washington Committee; James Farmer, National Director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); veteran socialist activist Norman Thomas; Executive Secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee James Forman; Freedom Rider Jim Peck; and Reverend Thomas Kilgore, Harlem Representative of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In this company, and in his public appearances, Baldwin was changing almost minute by minute, shifting his public image from a socially engaged—if tactically equivocal—literary success who guided readers’ self-reflection to that of prophetic celebrity-activist, unambiguously using his image and his words to advocate for immediate and structural, social transformation.

As radical as it may have seemed to some in November 1962 when it appeared in the New Yorker (and later in The Fire Next Time), Baldwin’s visionary call to action in “Letter from a Region in My Mind” still portrayed change as an introspective process modeled by an enlightened elite. This began with “the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks” who would exemplify change and, “like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others,” a process in which Baldwin’s writing would play an essential role. By September 22 Baldwin had begun to position himself in quite different company from the exemplars of liberal self-awareness who had been his ostensible colleagues in the past. In the place of “lonely activity” and “brutal isolation,” on podiums like the one in Foley Square on the National Day of Mourning, Baldwin urged people to “move, literally move, sit down, stand, walk, don’t go to work, don’t pay the rent,” and to join in “a massive campaign of civil disobedience. I mean nationwide.” Speaking in organized concert with the likes of Farmer, Forman, and Rustin, this new James Baldwin assured his listeners that “this is no stage joke” in attempts to induce collective action because “Some laws should not be obeyed.”

The day’s events included rallies, marches, and observances organized by the ten chairmen of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which itself had taken place a little more than three weeks before. The Day of Mourning was a kind of second March on Washington, but was much more radical in its declarations. Where the tone of the March was tactically modulated, the Day of Mourning was openly confrontational; while nonviolent, it was a militant, hard-edged follow-up to its conciliatory predecessor. It’s hard to resist the conclusion that the radicalism of the visions espoused that day—visions that had been actively suppressed in the March on August 28—is one reason why so few have ever heard of it. The legacy of the National Day of Mourning comprises a truly radical American document if there is one, one that couldn’t be carried along without chronic disturbance so it had to be forgotten. Such historical forgetting bears many ill effects. Among those, the erasure of the National Day of Mourning diminishes our radical basis for knowing—and so changing, creating—ourselves, each other, and thereby our world. Without such a radical basis for these transformations there’s no way to combat American commercial imperatives where the logic of buying, selling and owning, along with the brands—identities included—that facilitate the transactions, dominate all our patterns and perceptions.

It’s long past time to evaluate all these legacies: the legacy of the March on Washington, compromised, in its gilded historical frame; the legacy of murderous white supremacist assault and mass killing, events that still surround and imperil our contemporary lives; and the legacy of the National Day of Mourning, a radical American document that nobody’s ever heard of. This is also a story about why these stories are lost in the first place: how some of the most radical texts of our time have been buried in the archives often, one suspects, precisely because they are radical.

From one perspective these legacies might be read as bitter failures: the repressed figures of a nation still “so trapped and so immobilized” by division, as Baldwin had put it in Foley Square that afternoon. In light of that dire possibility, it’s worth our time to revisit the radical scripts put down by the visionaries and ordinary people alike who took part in that day: a day which offers a vision for our shared future, if there is one, as much as it does a lesson about our common past, if we ever had one.

I. Wednesday, September 18: “A warning but not a threat”

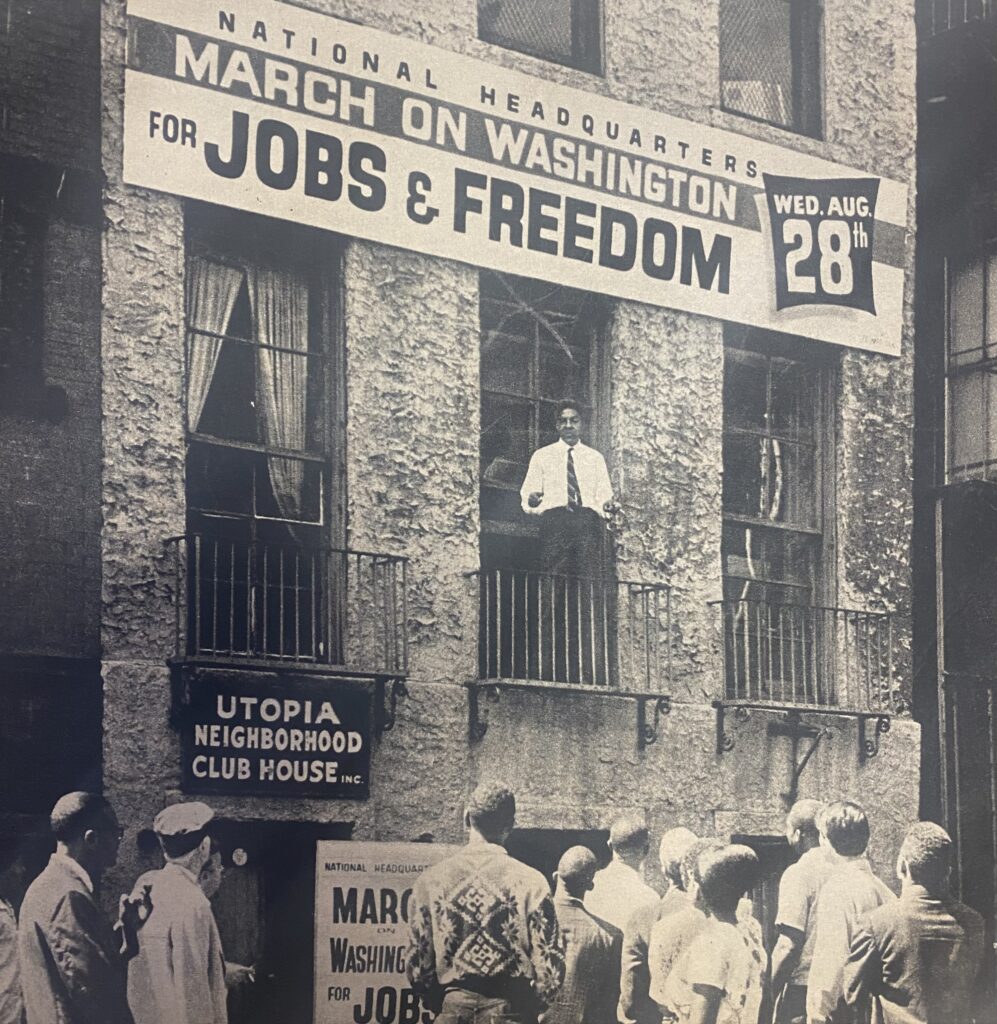

The public first heard of the Day of Mourning at a press conference on Wednesday, September 18 held by Baldwin and Rustin at the Utopia Neighborhood Club House in Harlem, which Rustin still used as the national headquarters for the March on Washington Committee. At the conference, Baldwin described the upcoming rallies across the nation as “a somewhat hideous sequel to the March on Washington” whose offices now formed the backdrop to his words. Speaking in obvious coordination with Rustin and other organizers, Baldwin told the press, “It is not enough to mourn the dead children. What we must do is oppose and immobilize the power that put them to death.” Anticipating his warning about Spain on Sunday, about how unanswered violence numbs the public and provides cover for fascist power grabs, Baldwin offered that “Birmingham, for America, may prove to be exactly what the Reichstag fire was to Germany. Let no one say that it can’t happen here. It happened here Sunday, and has been happening for a long, long time.” Set against the specter of Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Baldwin called for rallies and marches to issue “a warning, but not a threat” that Black people “are dangerously on the edge of violence, violence that could . . . spread across the nation” and lead to a period of truly cataclysmic white racist backlash, from mob action in the streets to undemocratic maneuvers by local and federal government.

Rustin echoed Baldwin. If federal response to the murders in Birmingham proved inadequate, he warned, Black people who up to then “have depended on non-violence as a means of protest” will “conclude they must provide protection for themselves.” The rallies should be totally separate from the federal government: calls by Black leaders for President Kennedy to use his power to declare the coming Sunday a national day of mourning were wrongheaded. Rustin argued that “it is quite useless for the President to think all his function is is to proclaim such a day. He must use his power to break Gov. George Wallace’s power.” Rustin and Baldwin both knew Kennedy wouldn’t invade Alabama, which Rustin knew would be fruitless in any case. As he’d convey in his brilliant speech on Sunday, the necessity was to gather the massive outpouring of grief at the atrocities of the previous Sunday and to guide that energy toward disciplined radical action. Such action, it was hoped, might move President Kennedy to confront Governor Wallace in Alabama, as well as his colleagues across the South, who were encouraging methods of “Massive Resistance” to desegregation in all its forms.

After Baldwin and Rustin made their prepared speeches, they adjourned outside as the afternoon, which had warmed into the high 70s, cooled into evening. Fern Eckman, Baldwin’s first biographer, captured the scene:

In the course of the next hour, [Baldwin] gave several versions of his speech for a string of networks and radio stations. Each of his statements was different. The theme remained the same, but the violence with which he phrased it increased. . . . ‘We are all responsible for Birmingham . . . President Kennedy—and his brother—and both political parties’ . . . Standing in the backyard, an area strewn with splintered glass, discarded tin cans, dead leaves, empty cartons, a broken chair and fragments of brick, Baldwin spoke into a latecomer’s microphone. ‘If you do not let these people go,’ he prophesized, ‘there will be blood in all American streets.’

As the last of the reporters filed out, Eckman watched as someone offered Baldwin “a cardboard container of coffee.” Baldwin’s response: “I need a scotch.” Strangely, Eckman’s biography, like all the other biographies of Baldwin, cuts off here. It includes not a word about the rest of the week and the Day of Mourning itself.

II. Friday afternoon, September 20: “You have to build a rat-proof democracy”

Two days later, a group called Artists and Writers for Justice had sprung into being and into action. Led by novelist John Oliver Killens along with Baldwin and actor Ruby Dee, the group sponsored a press conference in New York with Christopher and Maxine McNair, whose eleven-year-old daughter Denise was the youngest girl killed in the 16th Street bombing. Neither of the McNairs had ever been to New York City before. Just two days earlier, they’d been among the hundreds inside the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church in Birmingham as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Roy Wilkins (Executive Secretary of the NAACP) spoke at a joint funeral for their daughter and two of the three other girls killed in the bombing. That day King told the attendees (including the four thousand gathered outside the church) that this bombing had something to say to each person, including “every minister of the gospel who has remained silent behind the safety of stained-glass windows” and “every politician who has fed his constituents with the stale bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism.” “The innocent blood of these little girls,” King had said, “must serve as a revitalizing force to bring light to this dark city.”

On Friday afternoon the McNairs sat in a crowded fourth-floor room in the Astor Hotel, fielding questions about their daughter’s life and the implications of her death. Mr. McNair described raising his only child in a segregated world. When she was six, he remembered, she had smelled hamburgers in a Birmingham department store and wandered toward the lunch counter—not yet aware, at her age, that they wouldn’t be served there. “I told her there were certain people in this world that had no love, that certain places were off limits,” he recalled. A Tuskegee graduate, Mr. McNair spoke with obvious restraint and discipline; reporters from several papers stressed that there were no tears from either parent.

More questions followed. Who was to blame? Responded Mr. McNair: “I don’t know who to blame. I guess blame America. You can’t blame any one individual. It’s like asking who is responsible for the rats eating up all the corn. You build a rat-proof crib.” When asked about armed self-defense, a topic much in the air in the wake of the killings, he replied that “Such an effort would be fruitless. I’m not for that. What good would Denise have done with a machine gun in her hands?”

Without self-defense, then, and with even churches like 16th Street Baptist—where the couple had been married thirteen years before—as targets, would the McNairs consider leaving Birmingham? Milton Lewis recorded the response for the New York Herald Tribune:

‘No there’s no point in running away.’ Mr. McNair looked directly at a white reporter and said, ‘There is an unusual bond between Negroes whether it be a Black face in New York or in Birmingham. There is some sort of fraternity. Your face I must admit I’m in doubt. Please don’t misunderstand. There are Judases among us too.’

Mr. McNair struggled to translate what he saw as a path to progress in Birmingham, with its stark and absolute racial divisions, to reporters in New York City, where he wasn’t as sure who was who, exactly, and where he understood some formerly excluded ethnicities had shaken loose the stigma of ethnic difference and joined the mainstream. Lewis described how “Mr. McNair stopped talking for a moment. Then he tapped his left fist with his right forefinger and said . . . ‘I’m so easily identified as a Negro. There are Jew boys and Italians but they can get by. If you just let me get to that point I’ll get by.’”

Reports from the press conference stressed that Maxine McNair let her husband do most of the talking. But she made her points clear when she did speak. Since the bombing, they’d received messages of support from white people, she said—some of them anonymous, others not. Still, there was much work to do—in Birmingham and beyond. Violence like that which killed her daughter was not a local or regional danger; it posed a national threat. At one point, wrote Lewis, Mrs. McNair

leaned forward and drew an imaginary line on the carpeting in the hotel room and said: ‘Don’t think the fellows from the North are marooned off from the South. You have your demonstrations. It’s a problem for America. You got your problems here. You have rats in the South and rats in the North. You have to build a rat-proof democracy.’”

Asked about the search for the bombers who killed her daughter and the three other girls, Mrs. McNair recalled that there had been dozens of bombings in Birmingham and echoed the views of Baldwin and others that the FBI wasn’t doing all it could to investigate: “What are they waiting for? It embarrasses me. There have been bombings in one city for years. That speaks bad. They are able to pick up spies but they can’t catch a bomber in one city.”

The FBI was investigating, though. While the McNairs were meeting with the press, members of Artists and Writers for Justice planned the memorial service scheduled for later in the day. The Bureau, through wiretaps on attorney Clarence Jones’s phone, listened in. (At the time, Jones provided legal services and general support for Martin Luther King, Jr. and Baldwin.) The FBI’s taps gathered that “there would be a meeting of LOUIS LOMAX, RUBY DEE, JONES, and BALDWIN at 3:30 pm in Room 440 of Hotel Astor” to plan details of the memorial.

Despite their affiliations with King, who depended upon his collaboration with the president, Jones, Baldwin, and other members of the group resolved to voice their anger over President Kennedy’s weak response to the bombing. In Jones’s words, public comment from the White House had so far amounted to “about the most sophisticated insult you can give to the killing of” children. According to FBI transcripts, it was agreed that speakers at the memorial service “should make a strong statement” about President Kennedy’s weak responses to the atrocities in Birmingham, building off of the opening salvo launched by Baldwin and Rustin two days earlier.

III. Friday evening, September 20: “It should be an act of penance”

At 5 p.m. on Friday, Artists and Writers for Justice hosted a rally and memorial for the slain children at Town Hall on West 43rd Street in Manhattan. With the NcNairs among the eight hundred in attendance, Baldwin took the stage along with Killens, Lomax, and Dee to advocate for a national boycott of Christmas shopping. All elective shopping should cease until the nation had earned the right to do so, Baldwin said. Right now, the nation should be in mourning: “From a moral point there is something obscene about the way Christmas is handled anyways.” Or as Dee put it to the audience, “On Christmas morning mothers and fathers will say to their children, ‘Santa Claus didn’t come because bombers came in Birmingham.’”

Lomax concurred. The crimes like those in Birmingham, he said, testified to a guilt broader than investigations could locate and legal culpability could punish. Parents both Black and white had to take it upon themselves to explain the country’s violence to their children. All would need to explain why Santa Claus wouldn’t be coming that year. “Let them know that suffering is a collective thing,” said Lomax. “If any white child suffers then it will be etched in his mind and when he grows up he will remember what happened in Birmingham.”

As planned, President Kennedy’s tepid response to the bombings was another target of the day. Baldwin criticized Kennedy’s choices for a two-man delegation intended to mediate discussions between white and Black leaders in Birmingham. They were “an insult to all Negro people,” he said. And the choices were bizarre, if not outright offensive. One was former Army Secretary Kenneth Royall, who in 1942 had made his career defending the rights of Nazi spies captured in New Jersey and whose career had ended in 1949 when President Truman forced him to retire for refusing to implement Executive Order 9981 banning segregation in the armed forces. The other was retired West Point football coach Earl “Red” Blaik. Did President Kennedy get it at all? If he did, Lomax argued, he “should have taken [his daughter] Caroline by the hand and gone to the funeral” in Birmingham on Wednesday.

Instead, noted Killens, Kennedy had chosen to address the United Nations General Assembly earlier that day in Manhattan. The president spoke to the delegates of how “the clouds have lifted a little so that new rays of hope” for human rights could “break through” in West Berlin, Congo, and Laos. Meanwhile, in several confrontations, mounted NYPD officers prevented demonstrators angered by the Birmingham killings from getting near the UN complex. With demonstrators pinned down blocks away and turning their attention toward the precincts to which some of them had been taken after arrest, Kennedy told the UN: “We meet today in an atmosphere of rising hope and at a moment of comparative calm. My presence here today is not a sign of crisis, but of confidence.” To those on stage and, one supposes, in the audience at Town Hall that evening, the gulf between the open wounds and smoldering anger in Black Birmingham and the President’s message to the world about “rising hope” and “comparative calm” couldn’t have been wider.

IV. Sunday morning, September 22: “There’s a great paradox occurring”

On Sunday at 10 a.m. on the 22nd, Dr. Rev. Kilgore hosted a TV program which aired on WNBC, Channel Four, in New York City sponsored by the Protestant Council of New York City. It featured Baldwin and progressive theologian Reinhold Niebuhr discussing “the meaning of the Birmingham tragedy.” While often agreeing and remaining consummately cordial over differences in their views, the guests’ approaches differed markedly. Niebuhr sought an understanding of the incipient revolution in terms that explained it—and also contained it—while Baldwin searched for insights and openings to break the energies of dissent free.

Niebuhr observed that widespread social disengagement on the part of white churches had to do with theological ideas about purity, while many Black churches, inspired by King, were focused on social responsibility. Baldwin began his thoughts about nonviolent protest haltingly, noting that “there’s a great paradox occurring in this country,” and that, gesturing to Niebuhr,

what you say about the Negro church, for example, is, I think, entirely true, and Martin has used the Negro church, really, as a kind of tool, not only to liberate Negroes but to liberate the entire country. And on the basis of the evidence, and maybe overstating it a little bit, but as far as one can tell, the only people in the country at the moment who believe either in Christianity or the country are the most despised minority in it.

Gesturing to Kilgore on his right and Niebuhr on his left, and staring out beyond the camera as if searching for the words, Baldwin continued:

Negroes have done—with a really incredible, and agonized, restraint—more, it seems to me, in this decade to force Americans to begin to reassess themselves, than has been done since I was born. It’s ironical, I’m trying to say, that the people who were slaves here, the most beaten and despised people here, and for so long, should be at this moment, and I mean this, absolutely the only hope this country has. It doesn’t have any other.

Baldwin drew Niebuhr’s point about responsibility out further, saying that “none of the descendants of Europe seem to be able to do, or have taken on themselves to do, what Negroes are now trying to do. And this is not a chauvinistic or racial argument.” Speaking beyond strictly racial difference to the historical and experiential origins of Black people’s capacity to take up responsibility, Baldwin concluded his thought: “It probably has something to do with, um, with the nature of life itself, which forces”—here he reaches for Niebuhr’s arm—“you at any extremity, any extreme, to discover what you really live by, whereas most Americans have been, for so long, so safe and so sleepy that they don’t any longer have any real sense of what they live by. I think they really think that it may be Coca-Cola.”

While Baldwin lights a cigarette, Niebuhr expounds that “all through history it was the despised minority, the proletarians, the peasants, the poor who recaptured the heights and depths of faith, and the country itself choked in its own fat.” Focusing on the American present, Baldwin reframes Niebuhr’s theological point as an “immoral washing of the hands.” Pure or not, Baldwin argued, the inactivity of many millions of white people was “Morally irresponsible. Criminally irresponsible. ‘Cause this is their country too. What I’m trying to say is that I don’t suppose that everyone in Birmingham, all the white people in Birmingham, are monstrous people. But they’re mainly silent people. You know. And that is a crime in itself.”

In the face of Niebuhr’s abstract analysis and the neutral tones of Kilgore’s moderating, Baldwin almost visibly smolders, a new energy pulsing in his body. Forums such as these, he could already sense, lacked the urgency to match the radical stakes at hand. Picking up on the conundrum of American responsibility, Baldwin forged ahead:

It is a crime in this country now, a kind of moral crime, to suggest that there is something wrong with the economic structure. But there is something wrong with the economic structure. . . . You know I’m not asking for a ticket to Moscow or Peking; I am not, ladies and gentlemen, a communist. But it is time for us to look very hard at the facts of our life.

Apart from providing examples of Baldwin’s extemporaneous rhetorical skills, these moments offer clear glimpses of how the activist Baldwin appeared out of the James Baldwin who had become a literary success during the 1950s through brilliant performances of complexity and ambiguity on the pages of liberal magazines and eventually in the New Yorker. In his prefatory comment to Herbert Gold’s 1959 anthology Fiction of the Fifties, Baldwin allowed that he shared “the ideals of the West—freedom, justice, brotherhood” but that “finally for me the difficulty is to remain in touch with the private life. The private life, his own and that of others, is the writer’s subject.” Baldwin’s activist presence, emerging by degrees since the early 1960s and leaping onto the stage in the week following the bombing of 16th Street Baptist, departs markedly—radically—from his previous priorities.

Emphasizing collective and mutual action in public over “lonely activity” in private was new for Baldwin. Even less than a year before in The Fire Next Time, the book that established him as a celebrity and enabled him to cease careful negotiations with the literary world on its terms and turn the tables, Baldwin still mostly saw no way out. In his recreation of his dinner-debate with Elijah Muhammad, when Muhammad challenges him to assert his identity in terms that could stand up against those of the racist history surrounding them all, Baldwin manages only, “I’m a writer. I like doing things alone.” Even then, he knew very well this wasn’t enough, especially when considering people like those on Chicago’s “South Side—a million in captivity,” whose lives couldn’t be improved by the intellectual and aesthetic satisfaction of insoluble personal paradoxes. In the pages of the very book that made it real for him, he pondered his long-sought and hard-fought literary success. “What was its relevance,” he thought, when most people “didn’t even read?”

Baldwin’s role as a fast-radicalizing activist in the early 60s responded directly to this impasse. He now saw that while some people had embraced active responsibility in changing the world, and most of them needed to be freed, that alone wasn’t enough. Changing the country would require many, many more such people to be created. Furthermore, even the relatively conscious among Americans who, as he’d written in the The Fire Next Time, must “create the consciousness of the others” would need to do so by mutual, collective, and social action—more than private introspection. Though he doesn’t really offer an alternative in the book, maybe because the alternative wasn’t a book, The Fire Next Time made it clear that liberal self-reflection was a dead end, that “death by drowning is all that awaits one there.”

Paradoxically, the crucial, overlapping sexual revolutions that a mutual alchemizing of American identities would also entail, which Baldwin, as a writer, and especially in fiction, had been furiously exploring for a decade, remained—but for the bodies of speakers like Baldwin and Rustin themselves—mostly in the margins during the most public of these moments.

After a brief discussion of the politics and possibilities for Black armed self-defense, Kilgore concludes the program by addressing the audience: “This evening at three o’clock at Foley Square a meeting is being held to which all of the city is invited. . . . This is one way that you can show your interest in this great tragedy. Thank you.” Credits for the program appear across still photos of the destroyed 16th Street Baptist Church while a quiet, live recording of Pete Seeger and an audience singing “We Shall Overcome” plays in the background.

V. Sunday afternoon, September 22: “the cruelest and most abrupt terms”

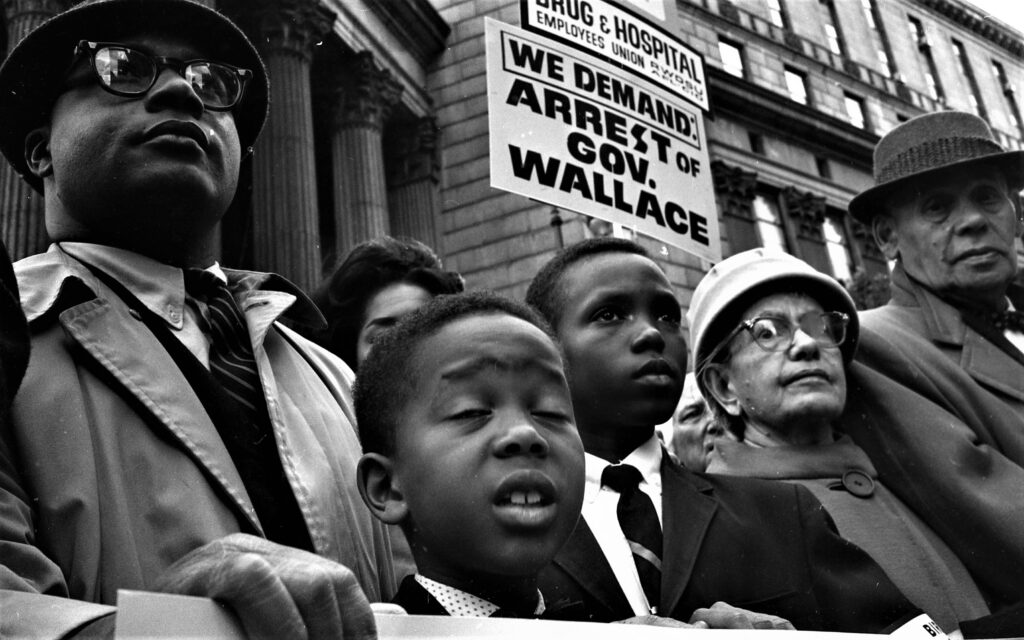

With thirteen thousand people gathered across the five boroughs of New York City, ten thousand in Washington, D.C., six thousand in Boston, three thousand in Miami, two thousand in Detroit, fifteen hundred in Des Moines, one thousand in Shreveport, and in rallies of proportionate size in at least three dozen other towns and cities across the country, the National Day of Mourning for the Children of Birmingham spread its impact widely. The “hideous sequel” to the March on Washington Baldwin had promised earlier in the week was playing out as planned. The gathered crowds took on local energies, some solemn, others militant, disseminating many of the messages that had been centralized—and in many cases compromised—in the march in D.C. the month prior.

But it was the day’s events in New York City that drew the largest crowds and the most coverage across the nation. On Monday the New York Times would cover Day of Mourning rallies at the top of the front page with a four-column photo of Norman Thomas on the stage at Foley Square and the headline: “Rallies in Nation Protest Killing of 6 in Alabama.” Under the headline read the subheading: “10,000 Cheer Denunciation of Kennedy Here—Mass Rights Uprising Urged.” Thousands gathered in Central Park, where New York Mayor Robert Wagner and U.S. Senator Jacob Javits addressed the attendees with calls for unity. In the Bronx, where eight children carried four mock coffins in the march, Herb Callender, chairman of the Bronx chapter of CORE, challenged the 1000 people in the audience to “write letters to Mrs. Jacqueline Kennedy” and ask her to support the cause as “a symbol of motherhood.” A column of 2500, some carrying mock coffins as well, marched to St. Albans Memorial Park in Queens. And in Brooklyn, 4500 from 18 churches marched to Betsy Head Memorial Playground in Brownsville.

Of the events in the city, however, the rally at Foley Square was the largest and most radical. The sprawling audience gathered in the park faced a stage affixed with a banner decrying “Six Children Dead: When Will YOU Act!?!” The first to speak was activist, actor, and folk singer Theodore Bikel, clad in an all-black suit and tie. Born to a Jewish family in Austria who fled the Nazis to London and then to the United States, Bikel described how being in Birmingham just weeks before the bombing brought back memories of Nazi hate from his childhood. After him, Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas spoke along with Harlem CORE organizer Blyden Jackson, who was in charge of the Foley Square event. Jackson called for the arrest of Alabama Governor George Wallace: “Instead of us filling up the jails with black folk, let’s put a few bad white folk in jail.”

The three major addresses to the crowd at Foley Square delivered by Baldwin, Farmer, and Rustin were the most militant of any reported from the events across the nation. Parting from the more idealistic messages of interfaith brotherhood, collective guilt, and the need for racial equality in other cities, the three men stressed the need for immediate, coherent, and disruptive action.

In his speech, later titled “We Can Change the Country,” from the stage at Foley Square, Baldwin argued that “this unprecedented revolution” was unlike anticolonial struggles in places like Cuba and Congo in that “we cannot take over the land. . . . The terms of this revolution are precisely these: that we will learn to live together here or all of us will abruptly stop living.” Echoing fears lingering on from the missile crisis in Cuba the previous October, Baldwin actually had another kind of annihilation in mind: a much more intimate and mutual social annihilation. He continued, saying “We are living, at the moment, through a terrifying crisis” and then resolved to describe the nature of this unique kind of revolution “in the cruelest and most abrupt terms” he could find:

It is the American Republic—repeat, the American Republic—which created something which they call a ‘nigger.’ They created it out of necessities of their own. The nature of the crisis is that I am not a ‘nigger’—I never was. I am a man. The question with which the country is confronted is this: Why do you need a ‘nigger’ in the first place, and what are you going to do about him now that he’s moved out of his place?

Where in Baldwin’s mind anticolonial revolutions had to do with repossessing land, the American crisis entailed a revolution in identities which needed to be remade. And this was only part of Baldwin’s fast-radicalizing vision. The rest involved immediate interventions into the country’s economic and social structure. These two elements of the revolution that Baldwin described that day in Foley Square were not disconnected. In fact, in retrospect, and in ways the novels from his mid- and late career explore in rich detail, it’s clear that intervening into the structure of American life would entail all kinds of endeavors, many of them mutual and collective, and that this experience would be the remaking of identities. Baldwin knew this making and remaking was already underway. His real question was, would Americans be able to take part in the ways each other’s lives were changing or not? And if not, that’s what he meant when he talked about “all of us abruptly stop living.” The odds were long, but these were the true stakes.

The bombing of 16th St. Baptist and the murders that followed it on the previous Sunday were but the most hideous features of Americans’ war against their own and each other’s lives. Aiming the audience at this vital and volatile situation, Baldwin said: “Now there are several concrete and dangerous things that we must do to prevent the murder—and please remember there are several million ways to murder—of future children (by which I mean both black and white children) … And one of them … is to take a very hard look at our economic structure and our political institutions.” Baldwin knew that Northerners loved to cite Southern segregation as a way to avoid dealing with structural racism in the North. His speech made it very clear, as he had that morning on TV, that social restructuring would involve everyone’s identity. He knew this was the only hope, however dim. So he charged ahead:

New York is a segregated city. It is not segregated by accident; it is not an act of God that keeps the Negroes in Harlem. It is real estate boards and the banks that do it … We’ve got to bring the cat out of hiding. And where is he? He’s hiding in the bank. We’ve got to flush him out. We have to begin a massive campaign of civil disobedience. I mean nationwide. And this is no stage joke. Some laws should not be obeyed.

Finishing with a call to action, Baldwin implored the crowd to “move, literally move, sit down, stand, walk, don’t go to work, don’t pay the rent, if we don’t now do everything in our power to change this country . . . The future is going to be worse than the past. . . . A government and a nation are not synonymous. We can change the government and we will.”

In a paragraph included by a few newspapers scattered across the United States and in Canada, Associated Press and United Press International reporting noted that Malcolm X, soon to be suspended from his post as the number two leader of the Nation of Islam, was in the crowd during the rally. Still working as spokesman for Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, he “disapproved of the number of white people attending, observing: ‘A cup of coffee is strong when it is black. When you mix it with cream it only dilutes it.’” But he was there.

Upon close scrutiny, Malcolm X appears in Morris Warman’s photo (published originally in the New York Herald Tribune) of Baldwin at the podium. At his height, Malcolm’s face is clearly visible over the crowd (just off the left margin of the photo and toward the top). Enlarging the image makes Malcolm’s face even more unmistakable.

Malcolm and Baldwin were acquainted. They had appeared together on radio and TV programs during the spring of 1961. On both occasions when they actually spoke, Malcolm was constrained to his role as charismatic mouthpiece for Nation of Islam doctrine and Baldwin, while acknowledging the truth in Malcolm’s scathing portrayals of white racism and political violence, criticized what he termed the “invented” racial heritage proposed by Nation of Islam theology. Malcolm clearly admired the precision of Baldwin’s fierce intelligence. The most powerful connection between the two would take place after Malcolm’s assassination. Especially in light of Malcolm’s rapidly developing sense of purpose and perspective during the last year of his life, Baldwin’s love and respect for him grew steadily in the decades to come. In this photo, which as far as I know is the only (and this only now) publicly available photo of Baldwin and Malcolm in the same frame, we can see that Malcolm, who, despite Nation of Islam doctrine prohibiting active political engagement, was eager to join in the fight, and with whatever misgivings he had about all the cream in the crowd around him, listens intently to what Baldwin had to say. Looking very closely, it appears he may even be holding a microphone to record the speech.

VI. Farmer and Rustin: “Creative Disruption”

Baldwin’s work was mostly to draw a crowd and set the stage, which he’d done. The speakers who followed deployed a well-honed rhetoric of radical persuasion. A veteran nonviolent activist who had led the founding of CORE in the early 1940s and organized the “Freedom Rides” during the summer of 1961, Farmer cleared away all middle ground in his speech. There was strength and mutual transformation through disciplined, purposeful action on one side and complicity with murderers on the other. In Farmer’s vision bombs were always blasting away at citizens of all kinds. Poverty, child mortality, discrimination in housing and employment: all of it bombed Black and poor communities, “agonized babies . . . their mothers, in many cases, undernourished, for they’re poor and work too hard. . . . The bomb is bigger than Birmingham. The bomb is as big as our country.” Farmer’s speech leaves no safe spaces. Apathy and affluence blast away too. “Grieve too for the Negro who says: I have made it. I will get me a car as big as your house and have me a good time and die,” Farmer thundered. “Mourn him. He helped throw the bomb too . . . On Election Day, the man who is not registered and who stands on a street corner thinking thoughts far away—that man with idle hands is manufacturing the bombs for a hundred Birminghams.” Farmer’s call to action meant to touch everyone, to implicate everyone and then urge all

to become an intimate part of this movement . . . There are no innocent bystanders now. If you are a bystander, you are guilty. . . . The call is Freedom Now. . . . and if the administration will not move, then the administration will be replaced.

Last up was Rustin: a true American radical, and an even more expert and experienced nonviolent activist and organizer than Farmer. Rustin had helped organize and execute the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, the first Freedom Rides, riding in integrated company across the Upper South on buses. He had been jailed and imprisoned many times, including spending three weeks on the chain gang in North Carolina in 1947 during the Journey of Reconciliation. In 1955 he had traveled to Montgomery to help Martin Luther King and others there organize the bus boycott and, despite fears over publicity about his being gay, which Rustin never hid, he’d been the lead organizer of the March on Washington the previous month. Considering how it followed the March as it did, and also looking at it in light of how King’s “I Have a Dream” speech—and only part of that—has been made to resound in our historical memory, Rustin’s speech at Foley Square reads like a methodical release, or return, of all the radical energy and rational necessity siphoned out of the program at the March in August leading critics like Malcolm X to refer to the day as “a sellout . . . a takeover.”

Connecting the widespread feeling of promise from August to the need for immediate radicalization, Rustin started by praising the March on Washington for how it “broadened the base of the civil rights movement.” “The Negro needed allies,” Rustin explained, because “the Negro revolt had, quite properly, begun to become a revolution.” However inadequate the March’s political program had been, it was nonetheless a “crucial first step.” The rest of the steps, though, would need to advance quickly—and radically. Rustin acknowledged that “Kennedy is the smartest politician we have had in a long time” but explained that his intelligence accounts for why he “bows to the Dixiecrats and gives them Southern racist judges” often in contrast to more liberal appointments made by Eisenhower. Kennedy’s “anachronistic foreign policy” and domestic inaction together with rampant racist police brutality and “the abysmal failure of the FBI to do its job” all made it clear, in Rustin’s view, that American possibility could only come from the transformational force of committed nonviolent direct action. This action would produce the cauldron in which Baldwin’s revolution in American identity just might be alchemized. Meanwhile, the status quo functioned like the multidimensional “bomb blast[s]” Farmer’s speech described and, Rustin argued, federal intervention—either by troops or through reforms—could do little more than “defend the status quo.” “We need protection” of the sort that federal legislation could provide, Rustin allowed, “but we need protection and progress.” And progress could only be won through mass action.

Rustin concluded his speech with a section titled “Creative Disruption.” The only plausible route, he felt, to both the structural intervention implored by Farmer and the interpersonal transformation without which Baldwin had warned Americans will “abruptly stop living,” was radical action:

The need of the civil rights movement is not to get someone else to manipulate power. They will not do it in our interests. Our need is to exert our own power, and the main power we have is the power of our black bodies, backed by the bodies of as many white people who will stand with us. We need to use these bodies to create a situation in which society cannot function without yielding to our just demands.

He addressed the question of violence not as a tactical question of revolt but as an inevitable consequence of the status quo, stating that

we cannot get our freedom with guns. You cannot integrate a school or get a job with a machine gun. The only way we can do these things is to use our bodies in such a way that the school or factory cannot operate successfully without integrating us. The same holds true for our pressing overall demands . . . We need go into the streets all over the country and to make a mountain of creative social confusion until the power structure is altered.

Rather than the spiritual “mountain . . . made low” that King invoked in his speech at the March on Washington, Rustin offered the crowd at Foley Square, and by extension the nation as a whole, another kind of mountain to envision, one where creative collective action could transform the institutions of inequality while, in the process, creating an experience of active American mutuality across the divisions enforced by those same structures.

Rustin knew this was quite a leap from the call made through compromise—one of which found Burt Lancaster reading Baldwin’s speech—at the Lincoln Memorial three weeks earlier, but he aimed to use the shock and grief over the murder of children to propose the only way the movement could pursue amelioration of people’s actual situation. As if to underscore that what often passes for rational is really fantastical and that what’s labelled radical is really the only rational course to take, Rustin concluded:

My words may seem extreme. But both the demands and the needs of the Negro people go so far beyond the present political possibilities that disruption is inevitable. The only question is whether violent or nonviolent, creative or uncreative . . . It is a question of program, of taking the offensive in an adequate way. For this, there must be masses in motion. There is no possibility of a practical program through violence. But unless those who organized and led the March on Washington hold together and give the people a program based on mass action, the whole situation will deteriorate and we will have violence, tragic self-defeating violence which will do immeasurable harm to whites and Negroes alike and will postpone indefinitely the day when all men will be free.

VII. Afterward: “Some big black cats … carried me away”

After the rally Baldwin would remember being surrounded by people seeking autographs and whatever else. Before he knew it he’d been surrounded and cut off from his guides. After a few minutes a group of Black men helped him make his way to a car waiting to take him from the scene. In a montage of comments from a 1965 tour in Italy, Baldwin recalled these very moments after the Foley Square march. His memories perfectly match a photograph Bob Adelman captured that day at Foley Square while assigned to Baldwin for an upcoming piece in Esquire.

“I got mobbed in Foley Square,” Baldwin recalled. “I was cut off from my friends by about 10,000 people. Everyone was friendly but there were so many people I was afraid. Some big black cats jumped on stage and carried me away.”

Baldwin was being carried away for sure. He’d been headed in that direction ever since the fame and money brought by the meteoric success of The Fire Next Time gave him a sense of power over the professional perils he’d been negotiating with since he was a teenager in Harlem with the mad fantasy of saving his family by becoming a famous writer. That long negotiation with the liberal literary agenda of the 1950s had almost finished him more than once. But it hadn’t. And now he was becoming convinced that his family couldn’t be saved, no one could be, until everyone was free. Since that seemed impossible, Baldwin resolved to do whatever he could, and then maybe a little more than that, and call that living.

And working, which he once told his brother David meant loving, which sounds romantic ‘til you really try it. In the fall of 1963, pivoting around the murders of six children in Birmingham, he set upon a path to see how much he could do, initiating a phase of radicalization that would lead him—with a few intervals off when he went to Turkey, or France, to write his next novel—to dedicate himself to working with the most militant of the civil rights activists at the time and, as the decade drew ahead, with the legacy of Malcolm X and with the next generation of radicals such as Stokely Carmichael, Huey Newton, Hakim Jamal, George Jackson and Angela Davis. That James Baldwin is another erased part of our radical history, and his work among colleagues preparing and performing the National Day of Mourning is a great place to begin to fill in the blanks; and to begin, again, the work of reimagining, and then remaking, ourselves and each other.

Boston Review is nonprofit, paywall-free, and reader-funded. To support work like this, please donate here.