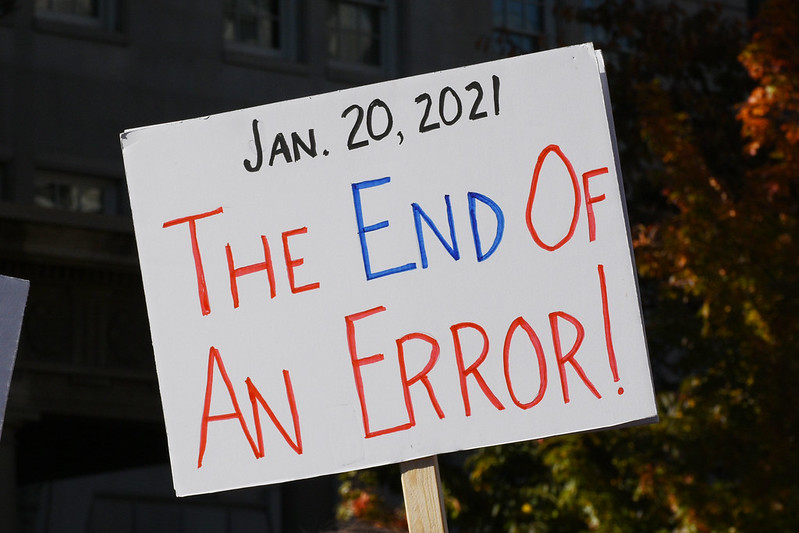

Last year Joe Biden began his presidential campaign with a simple premise: “I believe history will look back on four years of this president and all he embraces as an aberrant moment in time.” The question of whether Donald Trump really has been an aberration in U.S. history has dominated political discourse for years, and in the face of both Trump’s incessant antics and the upheavals of the pandemic, Biden positioned himself as the “return to normalcy” candidate. (Before 2020, that political rhetoric was perhaps most closely associated with the presidential campaign of Warren G. Harding a century ago.) Even though Biden himself has walked back some of this language on the campaign trail, it has served as the bedrock of his message. And it worked: it unseated an incumbent president for the first time in nearly three decades, even if with razor-thin margins in some states. But what do these claims of aberration and normalcy actually mean? The simplicity of messaging conceals a multiplicity of interpretations, each with their own implications for politics.

What do these claims of aberration and normalcy actually mean? The simplicity of messaging conceals a multiplicity of interpretations, each with their own implications for politics.

Take the aberration thesis first. Some observers focus on Trump’s personality. New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie, for instance, has wondered whether “there is anyone who can replicate Trumpism”—in particular, whether Trump’s “sui generis celebrity is his special sauce.” Certainly his personal charisma seems unique among high-profile Republicans today: it’s hard to imagine Tom Cotton, Josh Hawley, or Mike Pence working a crowd the same way, and his outsider past—in business and on TV, not in politics—certainly earned him a durable personal brand well before he was elected. But Trump is by no means the first outlandish celebrity to win high political office. There’s B-list movie actor Ronald Reagan, of course—though he also had a long career in Hollywood labor politics before running for governor of California—as well as his successor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Former professional wrestler Jesse Ventura ran a flamboyant and quirky campaign to win the 1998 Minnesota gubernatorial race on the Reform Party ticket. (Trump himself flirted with running for president as the Reform candidate in 2000.) Celebrity has often been a springboard to politics, particularly when it is tied to grossly exaggerated hypermasculinity.

Looking beyond charisma, Trump’s political message in 2016 was not particularly aberrant, either. For one thing, racism and xenophobia are tried and true national campaign strategies—and not just in the distant past. Pat Buchanan ran a similar campaign in 1992, telling reporters that he was “delighted to be proven right” by Trump’s victory four years ago. Nor is Trump’s penchant for conspiracy theorizing all that unusual. Birtherism was widespread among Republicans during Obama’s presidency, a sort of twenty-first-century analogue of John Birch Society conspiracy theories about Dwight Eisenhower being a secret communist. You do not have to agree with every argument in Richard Hofstadter’s famous essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” to acknowledge that the paranoid style really has been a constant in much of political life for a long while.

The truth is that a confluence of factors—slowing economic growth combined with a particularly weak Democratic candidate and racist backlash against the first African American president—helps to explain how Trump was first able to win the Republican Party nomination, then the presidency. And then there are the global trends: criticism of globalization, technocratic expertise, and well-educated elites has also succeeded in installing right-wing leaders in Brazil, India, Poland, and Hungary. Trump may seem to stand out as uniquely toxic, but he was in the right place at the right time for a political breakthrough.

One vision of “normal” politics values consensus and comity: building bridges, ratcheting down sectarianism, and forging a new national consensus.

If there is an aberration, then, it was not so much Trump himself, or even his political movement, but rather the inability of U.S. liberalism to offer a winning alternative. This failure strikes to the very core of Democratic political culture, which has prided itself on preventing the real extremists from taking power, on both the right and the left. When Ruth Bader Ginsberg called Trump an “aberration” last year, she also commented that “the pendulum goes too far to the right, it’s going to swing back. The same thing too far to the left.” To centrists, the political implications are obvious: now that liberal institutions have redeemed themselves, major reform is unnecessary—indeed must not be embraced, for fear of appearing too extreme. James Clyburn, the House minority whip, recently suggested that defund-the-police “sloganeering” cost the Democrats congressional seats. West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin blamed “socialism” for his party’s poor showing in the Senate races. The implication is clear: Democrats need to jettison—as Manchin called it—“a radical part of the so-called left.”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has vigorously rejected that conclusion; Doug Jones and Beto O’Rourke have echoed her. For them down-ballot losses are to blame not on visions for deep reform but on the Democratic Party’s weak organizing—its reliance on TV ads and parachuted-in candidates instead of robust grassroots mobilization. If Democratic leadership thinks running the same political playbook over and over again is going to work—either in terms of winning elections or quelling intraparty disputes—they’ve got another thing coming. Indeed, the modest Democratic victories this election are in some ways the real aberration. Republicans control the governorship and both legislative houses in twenty-two states. The Senate and Electoral College are fundamentally anti-democratic institutions, and the House of Representatives remains hopelessly gerrymandered. Anti-democratic dysfunction of our political system is a constant.

Given all this, what exactly does a return to “normalcy” mean? One answer is rhetorical and symbolic. The constant refrain that “this is not normal” has often been less political analysis than lament for a bygone moral order in political speech and leadership. Returning to normalcy, on this view, means a return to norms of civility and decency and a capacity for compassion. Trump is a malignant narcissist who cares nothing for other people’s pain and is endlessly rewarded for his sociopathy. Biden has suffered repeated traumas in life; his first wife and daughter were killed in a car accident, and his son Beau died tragically from brain cancer. Biden’s deeply personal experience with loss may resonate with a nation wracked with its own traumas.

There were no halcyon days of apolitical consensus. That conceit serves its own pernicious political end, obscuring the centrality of political conflict and political struggle in our national story.

But there is also a more strictly political interpretation of normalcy. Already we have seen calls for a kind of national reconciliation. In this paradigm, returning to normalcy means returning to an older, supposedly stable way of doing politics. Some of this is just Washington nostalgia for the days when Reagan and Tip O’Neill worked together to hash out legislation, or lawmakers from both sides of the aisle went out for dinner and drinks despite their political differences. This vision of “normal” politics values consensus and comity: returning to normal means that we must build bridges with our political opponents (this always means Democrats must reach out to Republicans, and not the other way around), ratchet down sectarianism, and forge a new national consensus—a world where both parties fundamentally agree on what America should be and the rules of the game and differ merely on minor points of interpretation. Biden himself campaigned on a version of this, predicting in 2019 that Republican leaders would have an “epiphany” once Trump left office and once again work in good faith with their Democratic colleagues.

But this conflation of normalcy with consensus is deeply flawed. The senior leaders in the Republican Party backing Trump’s baseless claims of massive voting fraud have hardly had an epiphany. And the truth is that bitter political conflict has been the norm throughout much of U.S. history. Even moments of seeming consensus—the New Deal era, the Cold War liberalism of the 1950s and 1960s—masked intense and often violent political struggle. Trade unionists fought police and the National Guard in the 1930s; civil rights activists braved waves of racial violence in the ‘50s and ‘60s. People died. And the U.S. right labeled them all as outsiders, agitators, or communists. At the height of the Cold War consensus in the early 1960s—the high water mark of “normalcy” in U.S. politics—the radical right-wing John Birch Society claimed that Dwight Eisenhower was a secret communist agent.

There were, in short, no halcyon days of apolitical consensus. That conceit serves its own pernicious political end, obscuring the centrality of political conflict and political struggle in our national story. And conflict is precisely what we see everywhere today. Trump’s voter fraud conspiracy theories will do long-lasting damage to trust in elections. Trumpism will remain a powerful force even without its leader in the oval office. The Biden-Harris electoral coalition looks weak. The Democratic Party’s problem appealing to Latino voters is likely to grow. Republican control of the Senate would mean ambitious structural reform is a dead letter, even if the Democrats had the stomach for it. If we are set to return to normalcy, it will almost surely be the normalcy of the Obama years, which saw stagnation, political gridlock—and, of course, the rise of Trump. That is not normalcy we can afford, and we must actively resist it.