Redistricting is underway in every state, and the segment of the population most likely to post large gains in representation is Hispanics. Hispanics constitute about 16 percent of the nation’s population, but hold only 24 U.S. House seats—5 percent. The number of Hispanic-held seats is expected to double as state legislatures draw new district lines to conform to legal requirements, most notably the Voting Rights Act. The VRA requires states with sizable minority populations to create as many districts as possible in which minority groups can elect candidates of their choosing.

Over the past three decades, as the VRA has been implemented and extended, the question of who the candidate of choice should be has been hotly debated. Is it better to create “majority-minority” districts or districts that will elect the candidate from the party (usually Democrats) that minority voters support? Much of the thinking and research about candidates of choice concerns African Americans, 90 percent of whom identify as Democrats. Relatively little is known about how Hispanics view their representation and what sort of representation they desire.

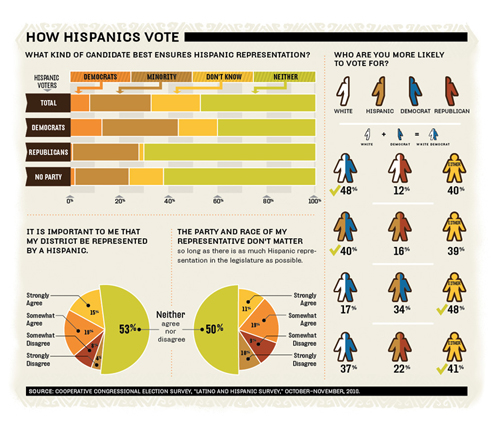

A survey of 1,200 Hispanic adults, conducted in English and Spanish and designed to be representative of the adult Hispanic population in the United States, found that Hispanics are not as overwhelmingly aligned with one party as African Americans are, but a large majority are Democrats. Sixty-one percent of Hispanics identify as Democrats, compared to 14 percent as Republicans and 19 percent as independents. By margins of three to one or better, Hispanics would choose a white or Hispanic Democrat over a white or Hispanic Republican.

When asked about their own representation, respondents gave a strong nod toward party. Only one-third of those surveyed say it is important to them to be represented by a Hispanic. A clear majority say that the racial composition of their district and the race of their representative are less important than the party of their representative and the majority party in the legislature.

While party matters more than race, Hispanics, asked again about their own representation, show a clear preference for their own racial group within a given party. A plurality would choose a Hispanic Republican over a white Republican or a Hispanic Democrat over a white Democrat. But party still trumps race. A clear plurality would choose a white Democrat over a Hispanic Republican.

Yet a different logic appears to apply in the case of group interests: when asked what is the best way to represent Hispanics as a whole, only 8 percent favor electing as many Democrats as possible, compared with 25 percent who would try to elect as many Hispanic officials as possible. The preference for race over party holds up among Hispanic Republicans and independents, too, though, interestingly, a plurality of all Hispanics say neither option—all-out support for a party or for Hispanics—is best.

Quite apart from the question arising from the VRA—who is a candidate of choice?—these data portend a deepening electoral problem for Republicans leading into 2012. Hispanics continue to grow as a share of the population and of the citizen population of voting age, and over the past decade their participation in elections has jumped dramatically. At a time when whites are expressing greater ambivalence toward both parties, Hispanics are developing stronger attachments to the Democrats, to the point where Democratic partisanship is now even stronger among Hispanics than their desire to elect Hispanics to Congress.