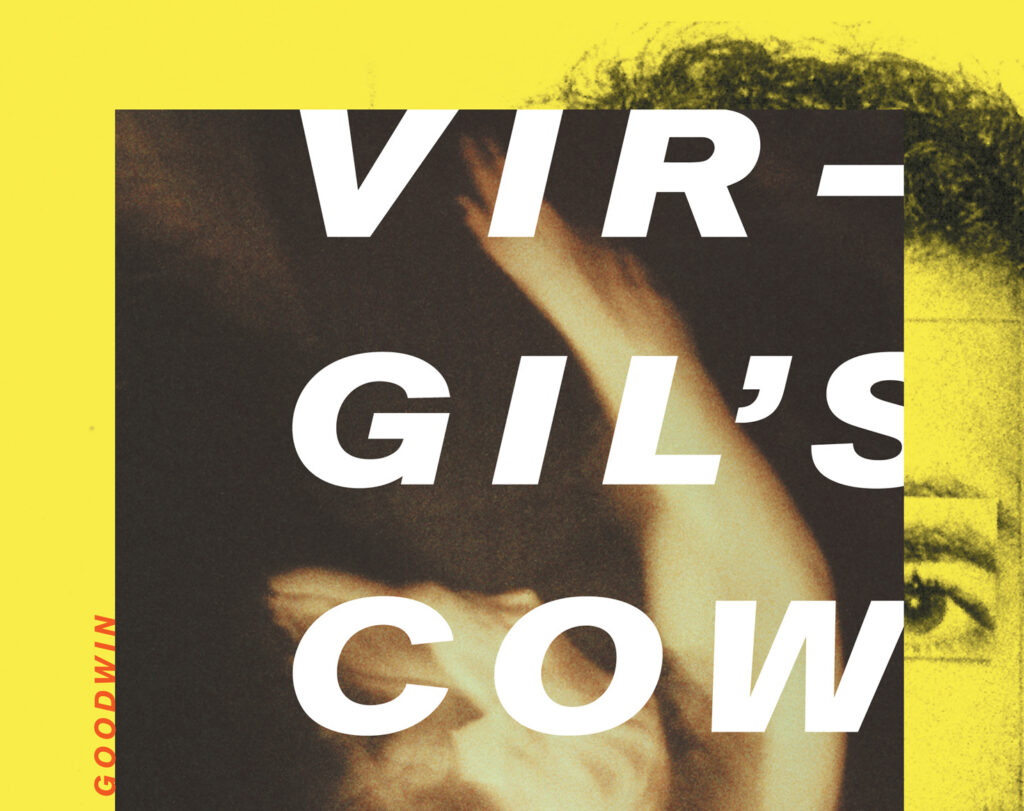

Virgil's Cow

Frederick Farryl Goodwin,

Miami University Press, $18 (paper)

Frederick Farryl Goodwin’s debut begins with Ophelia, ends with Horace, and is populated in between with a cast ranging from Merlin to Robert Mitchum to the Buddha. They appear not in conventional portraits but recast in the furnace of Goodwin’s aggressively anachronistic imagination. “‘Where have all the wise guys gone?’ cries Herod, from / the Bath House.” Virgil’s Cow operates sonically through traditional means such as alliteration and rhyme as well as through Goodwin’s pacing-based typography, which speeds up by slurred compounding (“w/ halfclosed eyes in a seaofthyme the angels’scarlet mouths caroused beneath myudders”) and slows through mid-word spacing (“I am d us ting for finger prints”). Yet what makes Virgil’s Cow seem so fresh is, ironically, its unapologetic engagement with classically poetic subjects, such as violence, madness, and love. Sexual desire, for instance, is referenced in the cow of the title—Virgil instructs that heifers be kept separate from bulls to prevent a violent contest, the roar from which would echo off Olympus. In Goodwin’s construction, the cow is hermaphroditic (a he-cow with udders) and instead of inciting an Olympic echo, his cow sniffs at the “Auroral R o a r”—that is, the ultra-powerful radio static created by the earth’s magnetic field. Goodwin’s interest lies not in separation, but in fusion, simultaneity, having it both ways—even if it means that “despite being surrounded on all sides by heavenly choirs / / you can / some days / still catch a glimpse of hell.”