This year marks the centenary of modernism’s annus mirabilis. For many, that means T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses—both first published in book form in 1922—perhaps along with the first English language translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. These books are in different genres and disciplines—poetry, fiction, philosophy—but all of them wed experimental literary aesthetics with highly abstract intellectual projects. All invoke myths to represent immense aesthetic and intellectual challenges: each tells of an arduous journey, that could, if successful, be redemptive, even transformative. Each text has its hero, but in each case the hero is also—or really—you. You, the reader, are challenged to find your way through these depths and heights and broad, rough seas. The journey is perilous, filled with traps as well as marvels. Should you succeed, your home may look different by the end; you will be changed too.

This account of these three notoriously difficult and undeniably monumental books is true, but it is also a product of a century of hype. These books are deliberately, self-consciously challenging, in content and in form. They are also hard, beautiful, powerful, and brilliant. That account of their greatness and difficulty, especially of the way their greatness and difficulty are entwined—they are great because they are difficult, and difficult because they are great—is a story that was itself invented.

The self-conscious mythologizing extended beyond the books to the authors and even the year itself. The myth of 1922 was made and spread by the writers themselves, along with their friends and enemies, their heirs and their fans. Eliot, reviewing Joyce, wrote, “In using the myth in manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity, Mr. Joyce is pursuing a method which others must pursue after him.” Ezra Pound wrote “The Christian Era ended at midnight on Oct. 29-30”—when Joyce finished writing Ulysses—and thereafter we are in “year 1 p.s.U.” that is, post-scriptum Ulysses. William Carlos Williams, not a fan, wrote that The Waste Land “wiped out our world as if an atom bomb had been dropped upon it.” Willa Cather famously grieved, “The world broke in two in 1922 or thereabouts”—the following year she won the Pulitzer Prize, and already she was considered a writer of the past. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby was a historical novel, set in 1922—just three years before it was published.

The myth was reinforced down through the decades by a cottage industry of academics. These texts are roughly as old as literary studies as an academic discipline, and analytic philosophy as the major Anglo-American philosophic tradition, and they were carried to their heights by countless college classes and the work of the professors who taught them. Hugh Kenner wrote the major scholarly books—over two dozen—that cast Eliot and Joyce, along with Pound, Williams, and several others (nearly all male, and all white) as modernism’s only slightly larger version of Romanticism’s so-called “Big Six.” (He, and others too, ignored or even obscured their racism and anti-Semitism.) Scholars more recently have written and edited books with 1922 in the title, Michael North and Jean-Michel Rabaté among them; along with work by Marjorie Perloff and others, they claim Wittgenstein as a central figure in modernism and, while broadening its main characters, further cement the status of the year.

Though the books live up to their hype, the mythic status of the year is wrong, misleading, and enraging in many ways. As North and Rabaté remind us, a lot more was published in 1922. Claude McKay’s Harlem Shadows and James Weldon Johnson’s Book of American Negro Poetry heralded the start of the Harlem Renaissance but for a long time didn’t count as factors in 1922’s wondrousness. Marcel Proust’s À la recherche des temps perdu also first appeared in English in 1922. Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room was published in 1922, as was César Vallejo’s Trilce. Why always The Waste Land, and Ulysses, and maybe the Tractatus?

The question points to a larger one. Although these three texts have cast long shadows for a hundred years, I’m not sure what happens next for them and for those of us who take them seriously. In the academic subfield of modernist studies, we have expanded the number of authors we study—a salutary and necessary advance—but as a result, “modernism” no longer clearly refers to the aesthetic movement of a particular time or place, nor to avant-garde or experimental aesthetics. And if modernism was carried to some prominence by the emergence of English as a central discipline for liberal arts in the twentieth-century university, what does it mean that the liberal arts—especially the humanities—are being eroded precipitously in universities today? I teach at a flagship public institution, and, like faculty in most universities these days, we do not regularly teach Ulysses to undergraduate English majors. The main reason is that we no longer have enough faculty. Every year several of my colleagues leave or retire and are not replaced; those of us who remain are spread thin covering surveys and skills-based classes; courses must be close to fully enrolled to run, and are books like Ulysses what our undergraduates want anyway? Those texts are so difficult.

It’s not controversial to describe modernist literature as challenging. Wittgenstein admitted to a potential publisher that the Tractatus would appear “strange,” and Eliot wrote that modern art “must be difficult.” Using The Waste Land as a case study, literary scholar Leonard Diepeveen argues in The Difficulties of Modernism (2003) that “the rapid proliferation of difficulty was an immediately noticeable characteristic of modernism, at times even going so far as to claim that difficulty, because of its preponderance, defined modernism.”

But there are many ways to be difficult; George Steiner, in his classic 1978 essay “On Difficulty,” identifies four. The first is contingent difficulty, which can be resolved with more information. These difficulties, Steiner writes, are “the most visible, they stick like burrs to the fabric of the text,” but “theoretically, there is somewhere a lexicon, a concordance, a manual of stars, a florilegium, a pandect of medicine, which will resolve” them. Then there is modal difficulty, whereby “large, sometime radiant, bodies of literature have receded from our present-day grasp” due mainly to the passage of time. Steiner’s third type of difficulty is tactical: when “the poet may choose to be obscure in order to achieve certain specific stylistic effects.” Last, there are ontological difficulties, which “confront us with blank questions about the nature of human speech, about the status of significance, about the necessity and purpose of the construct which we have, with more or less ready consensus, come to perceive as a poem.”

Some of the difficulties presented by Ulysses, The Waste Land, and the Tractatus can be described as contingent—susceptible to illumination by a manual of stars. In early 2020 the archive of 1,131 letters written between Eliot and his crush, friend, and muse, Emily Hale, was opened for the first time. These letters had been sealed at Princeton University’s Firestone Library until fifty years after Hale’s death. Their correspondence cast new light on The Waste Land’s hyacinth girl, who anchors the poem’s first section:

‘You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

‘They called me the hyacinth girl.’

—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

References in the letters make clear that this girl is not only an image from Eliot’s imagination, nor from literature or legend, like other figures in the poem, but also Emily Hale, a real person in a real memory.

But contingency is a minor difficulty. It can help to have Ulysses Annotated handy, especially if you don’t know much about Catholic liturgy or fin de siècle Irish politics. But it can also be a compilation of insignificance, even of red herrings, as are many of Eliot’s own annotations to The Waste Land. In the end, annotations can’t help that much. I tread carefully saying this because literary studies, for the past few decades, has been committed to the theoretical lens of New Historicism. Where the New Criticism of the mid-twentieth century insisted that literary texts are autonomous objects, the New Historicism that emerged in the 1980s insists they must be read in their cultural and historical contexts and can usefully supplement historiography. We’re all New Historicists these days—it would be intellectual negligence to ignore history when teaching or analyzing literature. And yet, when I once told a fellow modernist that I thought it was a mistake to think we are always making literary texts richer by contextualizing, she looked appalled, then furious. (This may have been partly why I wasn’t hired for a job in her department.)

Reading literature in its original context—describing ourselves as literary historians, as many of my colleagues and friends do—is one attempt to remedy the modal difficulties Steiner identifies. More context as a response to more distance: Is this project doomed to fail, or just never fully to succeed? As Steiner puts it, “We have done our homework, the sinews of the poem are manifest to us; but we do not feel ‘called upon,’ or ‘answerable to’” the text. Modal difficulty is a “failure of summoning and response.” I wonder if Eliot’s, Joyce’s, and Wittgenstein’s texts are starting to recede, if we are failing to call them forth from a hundred years ago, if our attempts to alleviate contingent difficulties can make modal ones worse, and vice versa. Once I would not have wondered these things—for a long time I felt like Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus were realer to me than I was to myself—but, a century after 1922, these books have become history in a way they weren’t when I first read them twenty years ago; when my maternal grandparents, both born in 1922, were still alive; when the Hale archives were still hidden; when I didn’t know how to pronounce Wittgenstein because I had only read the name; when Sweny’s Pharmacy was a stop on my young aspiring Joycean’s circuit of Dublin but still a drugstore and not yet a museum.

Ulysses and The Waste Land are themselves concerned with the presentness of the past, but both run their modal problems in the other direction: their pasts won’t stay past; these texts are haunted. In Ulysses, we meet, among other shades, the ghosts of Stephen’s mother, Bloom’s grandfather, father, mother, and young son. That first section of The Waste Land, the one with the hyacinth girl, is titled “The Burial of the Dead,” but throughout the poem, even at the end of that first section, the dead refuse to stay buried:

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: ‘Stetson!

‘You who were with me in the ships at Mylae!

‘That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

‘Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

‘Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

‘Oh keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

‘Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!

‘You! hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!’

Other examples of ostensible corpses rising in Eliot’s poem abound: Phlebas the Phoenician, Jesus of Nazareth, even the hyacinth girl is “neither / Living nor dead.”

In his 1919 essay, “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” Eliot famously argues that “the historical sense” is

indispensable to anyone who would continue to be a poet beyond his twenty-fifth year; and the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence; the historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order.

In other words, it is enabling for poets to be haunted. (Joyce might agree that it ultimately is for Bloom and Stephen as well.) But we should also remember that “Tradition and the Individual Talent” is one of New Criticism’s founding documents, which helped to inaugurate the discipline of English. So if these texts feel far away now—maybe not undead ghosts, but something else, something still alive but dim—how much of it is due not just to the passage of time, and not just to our failures as teachers or scholars to summon them and respond, but to our institutions? I am not talking about culture wars or canon wars or method wars or theory wars—there’s no real controversy among literary scholars about whether Ulysses is worth reading and teaching. Those wars are mere skirmishes compared to a larger struggle about the future of literary studies. Will it survive other than at the most elite institutions? Even there, will English go the way of classics—once central, now shrunken—but with creative writing in place of Latin?

Subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest essays, archival selections, and exclusive editorial content in your inbox.

Joyce said about Ulysses, “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.” This strikes me as over-optimistic these days—multiple centuries? Yes, there is still a Joyce industry in literary studies; the James Joyce Quarterly powers on, and Joyceans attend an annual conference. The Modernist Studies Association (MSA) Conference—this year with the theme of 1922’s centenary—is broader than ever and annually draws hundreds of us together to share ideas and discoveries. But there’s also a growing gap between increasingly gray tenured professors and always-young graduate students; there are very few in between, as young scholars try and are prevented from becoming professors because there simply aren’t jobs. I can easily count on one hand the number tenure-track jobs posted in the last five years, anywhere in the United States, for new professors who specialize in British, Irish, or American modernism. (At the MSA Conference this month, I was among just a handful of junior tenure-track faculty.)

Whether Joyce will keep us busy is not so certain, then, but Ulysses certainly could. Its dense contingent and modal difficulties could keep professors writing annotated editions and new historicist scholarship; then there are also its enigmas and puzzles and other tricks, like its shifting narrative and styles every chapter—forms of tactical difficulty. John Guillory has observed that the “the valorization of difficulty” was integral to New Criticism’s (notably exclusive) practices of canon formation, engendering a form of cultural capital that distinguished and justified university education. What Joyce says about himself—which I’m not at all convinced we should believe—is that his difficulties aim to achieve immortality for his novel. Yes, this is insufferably snobby in several ways, a claim to be undead and so never stay buried. But also yes—may it be so.

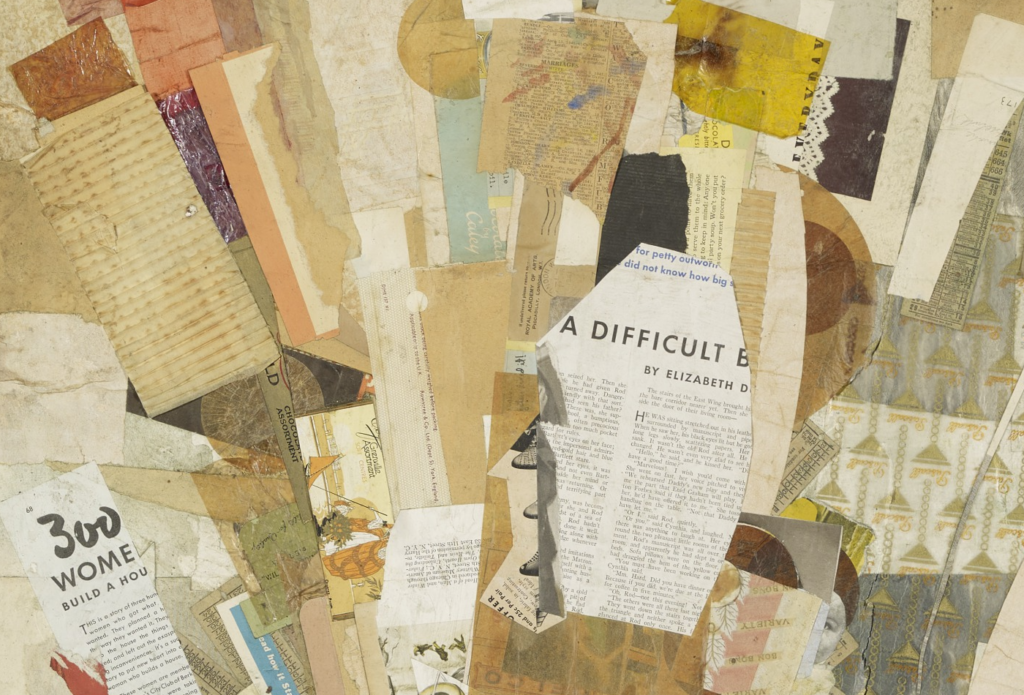

Students still feel Ulysses to be testing them, maybe even daring them to quit, but like any puzzle, tactical difficulty can become enjoyable. The Waste Land’s many voices and collage aesthetics once were considered tactically difficult, but they have gotten easier for readers now used to disorientation and instability. Students like playing along with a text’s games, and sometimes what’s hard is recognizing when it’s not a game, or when the game becomes serious.

What about ontological difficulty, the last of Steiner’s categories? “Difficulties of this category,” Steiner writes, “cannot be looked up; they cannot be resolved by genuine re-adjustment or artifice of sensibility; they are not an intentional technique.” Ontological difficulty is hard to talk about because it’s the difficulty of when “words fall short.” Words fall short when meaning-making is called into question or needs to proceed on different terms. Philosopher Cora Diamond, one of Wittgenstein’s great interpreters, describes reading a poem by Ted Hughes, itself describing a photograph of soldiers in World War I. For Diamond, the poem shows “a difficulty that pushes us beyond what we can think. To attempt to think it is to feel one’s thinking come unhinged.” In her recent book about modernist fiction and the Tractatus, Karen Zumhagen-Yekplé makes a similar point:

The Tractatus, after all, is a difficult text. It looks difficult in the way that we might imagine a logical-philosophical treatise should look. But the trick is that the real challenge of the book lies in the personally transformative work it demands of readers. . . . the logical theory we first thought made the book hard going was really not its true difficulty at all.

The question returns: Why always The Waste Land, Ulysses, and the Tractatus? Partly because they are difficult. But why are they so difficult? Because they tell us that we must change our thinking, and to change our thinking, we must change ourselves. This may sound mystical—Bertrand Russell famously called Wittgenstein a mystic—and Steiner writes about it that way: “By becoming linear, narrative, realistic, publicly focused, the art of Homer and his successors—this is to say the near-totality of western literature—had lost or betrayed the primal mystery of magic.” Literature that is ontologically difficult seeks to be an “insurgence” and an “attempted return” to when “language and thought had, somehow, been open to the truth of being, to the hidden sources of all meaning.” These books are myths about myths about myths—they are myths all the way down—but they’re not myths about nymphs changing into trees; they’re about us and how we may, and must, change.

But I’m not a very mystical person. A hundred years later, one of the things we have all become less mystical—or at least less mystified—about is the fact that the politics of many of the Anglo-American modernists were, broadly speaking, atrocious, ranging from aristocratically apolitical to self-indulgently libertarian to outright fascist. In 1928 Eliot described his politics as “royalist.” Joyce and Wittgenstein both flirted with socialism, but their political commitments were always fairly inscrutable.

What kind of difficulty do the terrible politics of the modernists create for their readers? Contingent, but not merely: references can be traced, but our condemnation is not and should not be lessened. Modal, arguably: these texts belonging to a hateful and frightening part of the past makes us wary of summoning them, all more so in light of the resurgence of hate and fright in our own time. Tactical: no; all is too evident. Ontological: certainly—Steiner writes that ontological difficulties are characteristic of modernism, and “they cannot be resolved.” They culminate in questions that ask “what allows us to discriminate . . . even between ‘the real’ and the ‘more real.’”

Which is real and which more real, the books or their authors? Ulysses, The Waste Land, and the Tractatus make possible perspectives and commitments, both political and ethical, that are not those of Joyce, Eliot, and Wittgenstein. The Vienna Circle of logical positivists took up the Tractatus as part of their directly anti-fascist epistemic project. More recently, the Tractatus has been read as a war book—Wittgenstein composed it as a foot soldier in the trenches, Perloff reminds us—and in this, it resembles how The Waste Land has been long received: a text concerned with making meaning in a nonsensical world, in fragments shored against ruin. In the wake of #MeToo, a new wave of scholars has returned to the poem’s depictions of gender and social power; similarly, we must remember Ulysses’s marvel of a last chapter, entirely in the mind of Molly Bloom, the central pull and pivot during that kaleidoscopic June day. And it matters that Leopold himself—ordinary, and Jewish—is the hero of the book. His great power is his ability to notice the wounded people around him, and he attempts to mend them, and maybe himself as well.

What made these books still more real for me is how I’ve changed by reading them, by taking their difficulty seriously. Twenty years ago, at the time I was first learning about modernism, I was also learning other things: how to be a good friend, how to have sex that I enjoy, how to clean a toilet, how to find common ground, how to compost, how to cook for a crowd, how to be politically active, how to write a rigorous argument. At that time I lived with sixty-some other people in a large cooperative house run by consensus. The difficulty of the books I was learning to read was only matched by the difficulty of building consensus, which taught me, over meetings that lasted many hours, the difference between needing and wanting. My housemates and I protested the Iraq War; as a legal observer, I stood on the sidewalk taking notes as one friend after another was arrested, went limp in the arms of the police, and was carried away. When everyone was home again and the bombings had begun, I was back to reading, I was forming—I remember—some argument about the beginning of Ulysses, visualizing its architecture in the air above my computer in golden lines.

Will you believe me that all of this felt of a piece? As I baked twelve loaves of bread on a Wednesday evening, as I read the next chapter of Ulysses in my extra-long twin bed while the loaves rose, as a housemate told me about our university’s use of temp labor or a friend about her parents’ divorce, as I pulled the loaves out of the oven, as I fell in love for the first time, I was trying very hard to discern what was important from what wasn’t—needing from wanting, what was real and what was more real—and everywhere I sensed those same ontological difficulties. I sensed them in in the kitchen, in the streets, in the library, in these books: how to see, how to decide, how to value, how to love. These problems are not New Critically autonomous—they are political questions.

When I go back to the Tractatus, The Waste Land, and Ulysses today, I find that they continue to help me with two entwined questions that are ontologically difficult and also really practical. (This is not at all a contradiction.) If I feel that I’m not sure what happens next for these books and those of us who take them seriously, well, that’s a feeling not too far off from the concerns of the modernists and their contemporaries: I’m not sure what happens next and how we continue to take the things we care about seriously. No one remembers 1922 any longer, but we have these books still. (I write these words on what would have been my grandfather’s hundredth birthday; he died in 2019 at the age of 97. I write at my desk with a lemon soap from Sweny’s Pharmacy, bought in Dublin on the centenary of Bloomsday when I was fresh from a college class on Ulysses, within reach on my bookshelf.) What was it like to be alive then, when—as Marshall Berman titles his book about modernism, quoting Marx—all that is solid was melting into air? Having lived through a pandemic unlike any seen in the last century, we might have a better sense of how to begin answering that question than when I first started asking it of my students as I was learning how to teach them ten years—and another world—ago.

What happens next and how to take things seriously are also difficulties that this set of texts has something to tell us about, something that we need, still—now—to learn. Diamond, along with another philosopher, James Conant, has one version of this answer in what’s come to be called “the resolute reading” of the Tractatus. The book takes the form of 526 numbered declarations (some contingently difficult with references to high-level philosophical logic, some tactically difficult in their puzzling language, some apparently straightforward). All are ostensibly about the relationship between language and the world. Then readers reach the penultimate entry, and the text offers a dilemma: we are told that everything we have read so far is nonsense and should be disregarded. “My propositions are elucidatory in this way,” Wittgenstein writes: “he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it.) He must surmount these propositions; then he sees the world rightly.”

Some have argued that Wittgenstein could not possibly have meant what he says here. Diamond and Conant argue he did. Readers should not “chicken out”—Diamond’s words—by trying to recuperate the meaningfulness of the rest of the book. We should not try to make the text cohere by softening or redefining what counts as nonsense; we should not try to understand the Tractatus as philosophical logic, even; we should realize that it’s changed in our hands because—Wittgenstein calls his philosophy therapeutic—it’s seeking to change us. If we are resolute, not being sure what happens next does not require clinging to our old ways of sense-making: it requires giving them up. At the same time, resolute reading does require continued seriousness; it also enables it.

There is something similar at work in Ulysses. Take the first chapter, “Telemachus.” (Joyce used these Homeric headings in his letters.) Stephen is living in Martello Tower with his frenemy Buck Mulligan. Contingent and modal difficulties abound in the book’s first twenty pages or so: there are references to Catholicism, classical literature, Shakespeare, the history and politics of Ireland, and more. Some of these difficulties are also tactical: the style is a little pompous, flowery and old-fashioned even for 1922 (except when it’s not, when a sentence fragment or odd image jolts); there’s too much missing information and also, sometimes, the information we have seems to be misdirection. At the end of the chapter, Buck asks for money and the key to the tower where they live. Stephen obliges and then thinks, “I will not sleep here tonight. Home also I cannot go. A voice sweettoned and sustained, called to him from the sea. Turning the curve he waved his hand. It called again. A sleek brown head, a seal’s, far out on the water, round. Usurper.” Stephen is, in a way, throwing away a ladder after he’s climbed it—or, because this is a tower, he has climbed down the ladder and is throwing it away behind him—but he is leaving and has nowhere to go, with resoluteness.

What does Stephen mean when he calls Buck “usurper”? While Odysseus was wandering for ten years, his son, Telemachus, was at home in Ithaca with his mother, Penelope. Her many suitors threatened to usurp Telemachus’s position; the worst and most dangerous was Antinous (in Ancient Greek, literally “counter-intellect” or “anti-meaning”). If we align Buck with Antinous, then we’ve solved a contingent difficulty by making it into a tactical one; a puzzle has been solved via a reference. Or really, the text tries to shove an ontological difficulty within a tactical one and turn that into a contingent one (a difficulty turducken?). But Stephen’s problems are difficult beyond solving with additional information, and I still believe that context doesn’t always help.

The first time Buck directly addresses Stephen, on the first page of the novel, he says, “The mockery of it. . . . your absurd name, an ancient Greek.” (He means Stephen’s last name, Dedalus.) A few pages later Buck refers to Stephen’s mourning clothing; his mother has recently died.

—How are the secondhand breeks?

—They fit well enough, Stephen answered.

. . .

— The mockery of it, [Buck] said contentedly.

Death, according to Buck, is “a beastly thing and nothing else. It simply doesn’t matter. . . . To me, it’s all a mockery and beastly.” Mockery, Joyce shows, is at odds with seriousness. (Buck even threatens to turn Stephen into a mocker as well, a secondhand version of Buck: calling Stephen by the nickname he gave him, he says, “Kinch, the loveliest mummer of them all!”)

Buck’s mockery works through language. His words about his mother are what hurts Stephen—“Stephen, shielding the gaping wounds which the words had left in his heart”—and language, not just Martello Tower, is what Buck is usurping. Throughout this first chapter Stephen tries to speak seriously about serious things, particularly about the loss of his mother, resisting Buck’s mockery. The first three sentences themselves are full of mockery—Buck mocks Catholic ritual, and the style mocks Victorian novels:

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed. A yellow dressinggown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind him by the mild morning air. He held the bowl aloft and intoned.

But Stephen is serious: “Silently, in a dream she had come to him after her death, her wasted body within its loose brown graveclothes giving off an odour of wax and rosewood, her breath, that had bent upon him, mute, reproachful, a faint odour of wetted ashes.” Stephen is trying to “see the world rightly” and recognize Buck’s words as senseless. He’s not sure what happens next, and he doesn’t know how to continue take serious things seriously. These are causally linked, though the causation can run in either direction: he doesn’t know what’s next because he doesn’t know how to take things seriously, and he doesn’t know how to take things seriously so he doesn’t know what’s next.

Of course I’m arguing for the continued importance and value of The Waste Land, Ulysses, and the Tractatus. And of course I wish I didn’t have to. But more than that, I’m arguing for seriousness, especially when it’s difficult. These texts are as well. Seriousness is difficult, and difficulty can be serious. Seriousness doesn’t stand against humor; it stands against unmeaning—nonsense and mockery. Philosopher Stanley Cavell—along with Diamond, one of Wittgenstein’s great heirs—writes that when he asked himself as a young man whether he was “serious about philosophy,” he sought to measure his answer “not by its importance (to the world, or to my society, or to me), but as measured by a question I felt a new confidence in being able to pose to myself, and which itself posed questions, since it was as obscure as it was fervent.” The question was “whether I could . . . mean every word I said.” Seriousness is not a defensive posture; it’s a stance but one that invites the discovery and making of meaning. It’s easier to chicken out, maybe increasingly easy. It’s difficult to be haunted.

I don’t know what happens next. My grandparents died; my mother got sick; I spent two very hard years at home for long stretches with my children, reading them Little Blue Truck and The Princess in Black (myths, of a sort). My little island, my intellectual home, is at risk, maybe already undone. But maybe not—I hope, and plan, and work, resolutely. I try to see and discern and value, in the classroom, in the air above my computer as I write, and in the world. I first read Ulysses twenty years ago, and ten years ago I wrote about Buck’s mockery in a grad school essay none of my professors ever saw. Twenty years of wandering, twenty years of these books—twenty percent of their time in this world—making my life more meaningful, more fervent if more obscure, more serious, but not easier. I’m grateful: I love them; I mean it.

Read a response to this essay by Marjorie Perloff.