Graffiti in Lesbos, Greece, birthplace of Sappho.

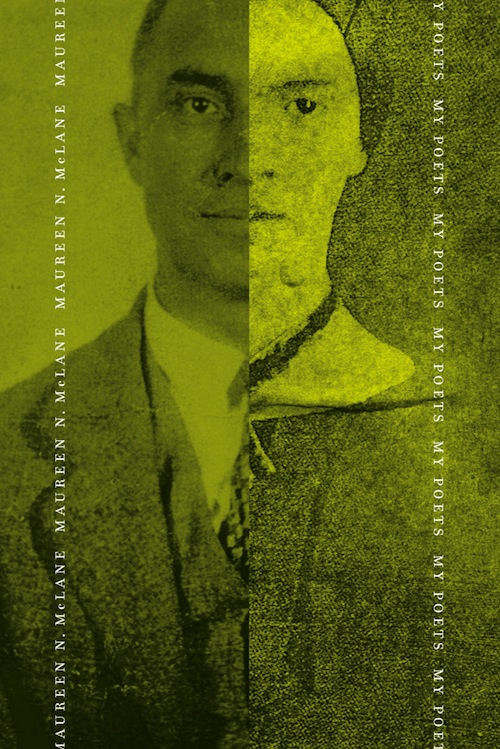

B. K. Fischer: My Poets has touched a nerve. In the year since its release in June 2012, the book has garnered not only critical accolades and numerous favorable reviews, but also the effusive adoration of readers who feel drawn to its unique braid of thought, citation, and analysis. Readers are charmed by the book’s abundant felicities of thought and phrase. We trust, at a very deep level, someone who can tell us something as right and true as the notion that “There should be a Marianne Moore brand of bourbon.” Part of the book’s appeal lies in its hybrid form—part memoir, part criticism—and in its capacious eclecticism in its treatment of canonical greats such as Gertrude Stein, Elizabeth Bishop, Moore, William Carlos Williams, and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

But the presence of razor-sharp critical acumen does not account for the book’s particularly emotive reception, in comment fields and private conversations as well as in reviewers’ efforts to characterize the book’s attractive force: it has been described in print as beguiling, charismatically subversive, endearing, roving, strange, haunting, iconoclastic, transfiguring, reveling, and incandescent. I’m not the first to point out, I’m sure, that most books of poetry criticism do not elicit the lexicon of magic. Now out in paperback, My Poets appeared recently on the New York Times paperback list. Has anything about the book’s reception surprised you?

Maureen N. McLane: Well, to be honest, any reception at all is a welcome surprise! And your account of this is very generous. I suppose I had kept expectations low on the reception front, as I tend to do, so I have been all the more pleased. The book is as you say a hybrid, and I wasn’t sure how or whether it would find an immediate audience, but certainly I hoped for one, and the positive responses have been wonderfully heartening. I’ve also been happy that the book has been reviewed for a general readership, not just for poetry aficionados—something I had hoped but had no confidence would happen. To get the sensitive, pointed, deeply thoughtful reviews the book did, at this moment in reviewing—when so many books are squeezed out—is definitely a surprise. And another delightful surprise—one I felt true to the book-as-memoir, but still a surprise in terms of worldly acknowledgment—was the nomination of My Poets for the National Book Critics Circle’s Award in autobiography.

I am very glad that people feel touched by the book, that it gives them a sense of permission; a number of people have told me that. I’ve been interested, too, to see that some readers focus on the book’s mode of essayistic writing, while others are oriented to questions of voice and revelation, and still others to matters of analysis. The book has led to all kinds of wonderful conversations; many students have told me they particularly respond to the chapter “My Impasses,” which is partly about my experience as a student—and in life!—of being muddled, of not getting it: not getting poems, or anything. Some friends who teach have given that chapter to their classes. It seems that the book can serve as a kind of prompt for readers’ own memories—of their own reading experiences, their own muddles, their own passions for poems or other works of art.

Hearing how the book has struck those kinds of chords has been extremely moving and rewarding. And I’ve also had the opportunity to talk about the book and its wellsprings in more formal conversations and interviews with terrifically astute poets and readers, like you, and Tess Taylor, and Adam Fitzgerald. So, inasmuch as the book conducts a kind of conversation with and inhabitation by poets, it’s been a delight to see that this kind of dynamic continues beyond the book.

Fischer: As a mixed-genre or cross-genre work in the tradition of Susan Howe’s My Emily Dickinson, My Poets draws on the resources of a variety of forms: cento, catechism, collage, memoir, satire and imitation, anaphora and oratory, as well as the various shapes of the prose essay itself—the chapters on Fanny Howe and Emily Dickinson first appeared as essays in Boston Review’s pages. The success of this hybrid form seems to me to lie in its recognition, and reminder, that our thoughts don’t stay put in disciplinary compartments. How relieved many of us are that someone has made this so clear! Interweaving criticism with memoir, combining personal history with the history of the critical faculties, has yielded an autobiography of the intelligence, truer to experience than forms that may abide disciplinary conventions or police their borders. In the mind, one thing leads to another.

I suspect, too, that readers of contemporary poetry and poetry criticism are tired of familiar models of lyric and narrative subjectivity and their rejection, or at least tired of the ways they tend to be talked about, through terms such as confession and fragmentation. We are grateful for the ways My Poets approaches subjectivity differently, as when you wryly dispense with the rigidity of the first-person domestic lyric: “I didn’t want to pay attention to the scrub of New Jersey. I had seen plenty of scrub; I’d had enough.” Has the work you did in writing My Poets, its inclusive embrace of fluid modes of articulating the self’s and the mind’s stories, changed the way you write poetry? Or, to take that question in either temporal direction, how does the work of My Poets intersect your poetic practice?

McLane: These are great, complex questions, and I think I am still in the middle of answering them. The book has in it several discrete poems—the centos, a poem concluding the Wallace Stevens chapter—so in certain ways the book itself registers my poetic practice. I don’t think writing My Poets has changed the way I write poetry; being a poet informs everything about My Poets.

Maybe I’m reversing the polarity of your question and you can redirect me, but I’d say, reflecting on this, that My Poets grew out of a simmering impatience with a kind of instrumental prose, with prose as information-delivery—whether in reviewing, standard nonfiction, whatever. I wanted to move along several axes simultaneously—to make a space for what Baudelaire called “a poetical prose.” It might be that the immersive experience of writing My Poets will lead to some more “essay poems”; I’d had one in my first book, Same Life—“Excursion Susan Sontag”—and there’s another, “Terran Life,” in my forthcoming book This Blue. But I don’t know in advance what the feedback loops will be among different modalities of writing. That was part of the excitement of writing My Poets—finding adequate form and exploring stylistic modes for different chapters: I was led on by lures and echoes and premonitions, so to speak, and in that sense the writing of these chapters resembled the writing of poems—as acts of discovery.

I am really hostile to disciplinary policing, even though disciplines, genres, and traditions are also enabling—deep wells for writing and horizons for reading. But the narcissism of minor differences—first person domestic lyric, as you say, versus whatever—ugh: so boring.

I should say too that I was very lucky in having the encouragement of places like Boston Review, where I’ve been a contributing editor for some years now: BR was receptive to this mode of writing, and as I began stretching my limbs this way, BR was the first forum I went to. Jonathan Galassi at Farrar, Straus and Giroux was behind this book from its very early phases, and his commitment was an incredible boon. The “My Fanny Howe” chapter grew out of an invitation to speak at an event celebrating her and her work—an invitation extended by Bill Corbett, poet and longtime resident of Boston, now Brooklyn. And the “My Impasses” chapter was part of a long piece for a conference on poetry and poetics organized by the scholar and critic Oren Izenberg (then at Chicago, now at Irvine): Oren wanted manifestos, not conventional critical prose, and I went with that. So, in a way, the seeds of things were planted by other poets (dead and alive), their readiness for conversation. And of course Susan Howe’s My Emily Dickinson offered one brilliant model of a poet’s prose, and behind that book, there was Williams’s In The American Grain and Charles Olson’s Call Me Ishmael, as well as Stein and much else. Anne Carson’s work, Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, Eula Biss’s work—all shone lights in the mental forest over the years.

My Poets grew out of a simmering impatience with a kind of instrumental prose.

Fischer: Much ink has been spilled, in Boston Review’s pages and elsewhere, on the institutionalization of the avant-garde in poetry in the past 30 years. As you channel Gertrude Stein, your statement here clears the smoke from the room: “Avant-gardes are necessary and disgusting and necessary to make one disgusted with prevailing and then with the avant-garde once it prevails. They are always borrowing from the future to hector the now.” If you have a crystal ball, or would like to pretend that you do, why do you think our literary moment is so obsessed with, and anxious about, the legacy of modernism, the value and impetus for innovation, and the hazards and necessities of canonicity?

McLane: Oh, I have no crystal ball, but a stab at your question would involve me in thoughts about historicity, cultural and literary capital, the “death of poetry,” and more recently announced deaths of literature, the humanities, etc. Is our moment more obsessed with modernism than, say, the poets of the 1960s were? I’m not sure. Maybe there’s a return to those early 20th-century poets as channeling a newly fresh wind; maybe post-confessional blahblah or conceptual whatever is just wearing us out (though maybe conceptual stuff is jazzing us too). Maybe make it new means make it old, and the oldsters look fresh and lively now. Over the past 50 years we’ve seen a great pluralization of recognizable, canonized—or at least anthologized—poetries: just consider the North American scene compared to the United Kingdom.

Regarding the institution of the avant-garde: I do think Pierre Bourdieu in The Rules of Art nailed this phenomenon years ago—the mutual imbrication of bourgeois (or let’s call it “mainstream” or “commercial”) art and avant-garde art that systematically rejects the former, yet in rejecting is structured by it. It’s interesting how much some versions of avant-gardism align with the planned obsolescence of capitalism. In the end, I’d rather think with self-announced avant-gardists than with self-announced custodial poets of notional tradition. How I might be brought to write is another thing, perhaps. That comes from other wells and soundscapes, other modes of reading, often in translation, or from song, from rhythms micro and macro.

I’m skeptical of writing under banners, though for some writers that is clearly enabling and leads to powerful work. I’m more interested in the longue durée, from Sappho (say) to Shelley to some young poet just starting to write now. I’m interested in structures and impulses, conveyances and surges—in what brings men and women to speech, to writing, to rhythmic transfer in and through language; how they formalize it, share it, transmit it. I do believe Shelley was right when he said that poetry was “connate with the origin of man”: this isn’t to mystify or idealize poetry but rather to emphasize that humans are beings in language and creatures of play. How that anthropological, ontological dimension reveals itself in any particular historical moment—well, that is another set of fascinating questions.

Fischer: I love that you’ve reminded us, in this précis that alights on a remarkable array of touchstones, that we are creatures of play. We’ve focused in this conversation on the critical and poetic insights to be gleaned from My Poets, but the book is also an autobiography of a reader, a document that at once attests to lifelong bibliophilia and also serves as a Virgilian beacon for readers who come after you. I’d follow you anywhere. What are you reading, for the play of thought, this summer? What contemporary poets are you reading right now? What novelists or critics? If you could drop everything and reread any book, this morning, for the sheer pleasure of it and for as long as you’d like, what would it be?

McLane: You’ve caught me at the right moment—I’m finally reading something other than Facebook updates and university emails. I’ve been reading Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse, and some Montale (Galassi’s translations)—thinking about Liguria, about Montale’s astringent and complex musics, about inheriting and torquing tradition, about stanzas and madrigals. Neither is a contemporary poet, but still . . . whatever’s live for you is contemporary, right? But in terms of contemporary poets: I’ve been reading (in galleys) Katie Peterson’s remarkable book Permission and will soon start her other forthcoming book, The Accounts. Her recent essay in Boston Review (on women poets, family, and convention) brought me to order Joanna Klink’s Raptus and Tanya Larkin’s My Scarlet Ways, and Christina Davis’s book too. I’m keen to read Evie Shockley’s The New Black, which I’ve had on a kind of pleasure-list for months. Others I’ve been recently immersed in: Ange Mlinko, Cathy Park Hong. Jeff Dolven’s wonderful Speculative Music is just out from Sarabande, and Daisy Fried’s Women’s Poetry. Eleni Sikelianos’s The Living Detail of the Living & the Dead looks to be channeling her singular poetic joy gene even amidst elegy. Whatever August Kleinzahler is writing: yes. Fiction: I await everything from Karen Russell’s pen, and Hilary Mantel’s. I might re-read some of Thomas Love Peacock’s novels—these weird, funny, early 19th-century satirical novels of ideas, largely in dialogue. Last summer I started reading Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s amazing epic novels of Indonesia—his Buru Quartet. I read two volumes and might continue. I’m pretty ambivalent about historical fiction but I found his work fascinating, not least in its formal and ideological resonances with a longer trajectory of historical fiction, from Walter Scott onward—how people think and feel their way through massive social and national change, how novelistic form can register these complexities.

Critics and other writing: I think n+1 is publishing consistently riveting work; Elaine Blair is fantastic and proves that younger women can actually write for the New York Review of Books. I gather that Elif Batuman is writing a novel—her essays are so extraordinary, and her feel for what the novel can do so supple and alive, that I will be eager to read it, as well as anything else she is publishing. Vanessa Place: spine-straightening.

Isn’t Lena Dunham writing a book? That I will definitely read. I’m not a Dunham-hater; I’m a hater of haters. Ditto Sheila Heti. I’m hovering over whether to read the George R. R. Martin Game of Thrones books, but I think I’m going to stick solely with the televisual experience. Oy.

In terms of re-reading: for sheer and total pleasure, my candidate would definitely be Proust. I hold off re-immersing because I know if I started again I would wish to swim uninterrupted in those waters for weeks—and maybe later this summer I’ll have that chance. On Bloomsday I was thinking: Proust v. Joyce, who would win? PROUST. (A side note: there can be a strange melancholia involved in re-reading, and I feel I have to station myself against that. Am I really ready for this overwhelming experience again, its new or different resonances? I remember that phenomenon years ago, when re-reading Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway—it was devastating, and I was devastated, as well as exhilarated. These are experiences one doesn’t casually repeat or revisit.)

At the moment I’m more skimming and skittering than reading: but, looking forward. Sumer is icumen in, Lhude sing cuccu!

Photograph: D1v1d/flickr