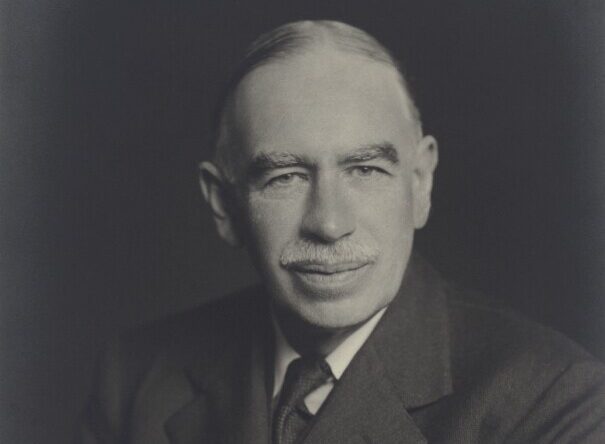

The Keynes Solution: The Path to Global Economic Prosperity

Paul Davidson

Palgrave Macmillan, $22 (cloth)

Keynes: The Rise, Fall, and Return of the 20th Century’s Most Influential Economist

Peter Clarke

Bloomsbury Press, $2o (cloth)

Keynes: The Return of the Master

Robert Skidelsky

Public Affairs, $25.95 (cloth)

“Keynes is back.” It is a familiar cliché, but also an enigma. Enigmatic, first, because Keynes, the most influential economist of the twentieth century, never really left. Like it or not, we live in a macroeconomic world elucidated by Keynes and those who followed in his footsteps. Even Robert Lucas, who won a Nobel Prize for his criticisms of conventional Keynesianism, said in response to the financial crisis: “I guess everyone is a Keynesian in a foxhole.”

But enigmatic also because Keynes himself was never with us. From his vast writings, a few ideas were quickly distilled into analytical tools and policy prescriptions that became known as “Keynesianism.”

This produced some stark differences between Keynes’s ideas and those that bore his name. Once, after a wartime meeting with American economists, Keynes observed, “I was the only non-Keynesian in the room.” Following his death in 1946, the divergence only grew. And in due course, even the Keynesian distillate was superseded by shifts in economic theory and overtaken by events, especially the stagflation of the 1970s, the political climate of the 1980s, and the ideological triumphalism of the post–Cold War 1990s. With Keynes himself gone, and Keynesianism losing its grip, the policy choices in the decade leading up to the great financial crisis of 2007-08 were the unhappy but predictable result.

Just what did Keynes believe?

Keynes thought that most markets work well most of the time, and that there is no economically viable substitute (or attractive philosophical alternative) to undirected individuals pursuing their idiosyncratic interests, guided by a well-functioning price mechanism.

But Keynes also knew that some markets don’t work some of the time, and a few markets, in particular circumstances, perform dismally. He devoted much of his career to addressing these dysfunctions, with three main concerns: first, that an economy, once stuck in a rut, often will be unable to right itself on its own; second, that financial markets—driven, for better and worse, by herd behavior, uncertainty, and unpredictable shifts in the attitudes and emotions that he called “animal spirits”—are inherently prone to destructive cycles and panics; and third, that an unregulated international monetary system tends to veer toward unsustainable disequilibria and always presents inescapable dilemmas of balancing domestic and international monetary stability.

These problems—self-reinforcing economic ruts, financial panics, and global instability—are painfully familiar, and they should remind us why there is much to be gained from rediscovering Keynes: not simply returning to “Keynesianism,” but searching out the master himself. The authors of three new books on Keynes are eager, and well-situated, to seize this opportunity.

Paul Davidson is one of the leading scholars of the “post-Keynesian” school. While most American economists moved from Paul Samuelson’s “Neo-classical Synthesis” to an ever-more circumspect (modestly interventionist) “New Keynesianism,” the post-Keynesians emphasized two of Keynes’s ideas that the more conventional view minimized: the importance of uncertainty and the “non-neutrality of money” (the idea that changes in money supply affect growth rates and other real economic variables, and not only prices). Peter Clarke wrote the important study The Keynesian Revolution in the Making, which explores Keynes’s intellectual journey. In his 1924 Tract on Monetary Reform, Keynes shows his gifts, but remains fairly mainstream. By 1930 his increasingly creative prescriptions for the struggling British economy culminate in A Treatise on Money. And from there, The General Theory (1936), with its comprehensive dissent from the classical school, rooted in Keynes’s conclusions about problems inherent in laissez-faire capitalism. Finally, Robert Skidelsky is author of a justly celebrated three-volume biography of Keynes.

Each scholar’s new book reflects his distinct intellectual engagement with Keynes, but collectively they point in a common direction. Keynes, they suggest, would argue that our current mess has three main causes: failures of the economics profession, mistakes by government, and regrettable social trends.

To appreciate the charge about the economics profession, we need to understand the practical and analytical vulnerabilities of 1960s Keynesianism. On the practical side, Keynesianism foundered on the supply shocks of the 1970s. On the analytical side, Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps pointed out that Keynesian models failed to take into account that individuals adapt their expectations to new circumstances, including policy interventions, and that those adaptations might prevent Keynesian policies from achieving their desired results.

In the 1980s and ’90s New Keynesianism sought to respond to this criticism by integrating “rational expectations” into its analysis. But as the economist James Tobin complained, this was New Keynesianism without Keynes. In particular, Keynes did not assume any kind of rational expectations—the idea that individuals, armed with a (shared) knowledge of the (singularly correct) model of how the economy functioned, would instantly, efficiently, and dispassionately optimize choices in an information-rich environment. On the contrary, he emphasized the central role of animal spirits, of daring and ambitious entrepreneurs taking risks and placing bets in a highly uncertain economic environment characterized by crucial unknowns and unknowables.

Uncertainty, as Clarke argues in Keynes: The Rise, Fall, and Return of the 20th Century’s Most Influential Economist, is a “guiding insight at the heart of Keynes’ intellectual revolution.” Davidson and Skidelsky also drive the point home in The Keynes Solution: The Path to Global Economic Prosperity and Keynes: The Return of the Master, respectively. Keynes identified his treatment of expectations about the future as a principal point of departure from the reigning perspective. “The orthodox theory assumes that we have a knowledge of the future of a kind quite different from that which we actually possess,” Keynes explained. “This hypothesis of a calculable future leads to a wrong interpretation of the principles of behavior . . . and to an underestimation of the concealed factors of utter doubt, precariousness, hope and fear.”

Many mainstream economists came to embrace the idea of rational expectations and its partner the “efficient markets hypothesis,” which holds that current market prices accurately express the underlying value of an asset because they reflect the sum of a collective, rational calculus. Keynes, however, held that investors more often grope in the dark than calculate risk—they can’t assign precise probabilities to all potential eventualities because too many factors are unknowable. Faced with this uncertainty, investors inevitably place great weight on the apparent expectations of others. Thus, as Keynes famously argued, investors need to make their best guesses not simply about the likely business environment, but also about the guesses of other investors regarding that environment. The resulting herd-like behavior can at times generate dysfunctional consequences, such as self-fulfilling prognostications of financial crisis.

Embracing rational expectations and the efficient markets hypothesis led the economics profession to make disastrously misguided assumptions about the stability and self-correcting hyper-rationality of financial markets in particular. The government’s failure was to embrace these errors of the economics community and run with them. Davidson holds that the origin of the current crisis “lies in the operation of free (unregulated) financial markets.” “Liberalized financial markets,” he argues, “could not heal the bloodletting that they had caused.”

Those markets did not liberalize themselves, of course. Since the 1980s public policy has embraced with increasing momentum the idea that once set free, financial markets take care of themselves. Thus the push by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the mid-1990s to force states to eliminate their capital controls, and the 1999 repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act: both instances of dismantling regulations designed to avoid the horrors of the Great Depression. Glass-Steagall built firewalls to prevent another collapse of the banking system; prudent capital controls aimed to mitigate the tendency of the international monetary system to transmit destabilizing shocks across borders. “Nothing is more certain than that the movement of capital funds must be regulated,” Keynes insisted, as one of the key architects of the IMF.

These books suggest that Keynes also would have found something troubling about contemporary Western society, or at least the version of it that emerged in the post–Cold War United States. Keynes’s economics was rooted, always, in a normative, philosophical vision, in particular that the economic game was not about winning the candle. This was one of Skidelsky’s great contributions in his biography, and Return of the Master treats us to a chapter on “Keynes and the Ethics of Capitalism,” including Keynes’s aversion to “the objectless pursuit of wealth.” Rather, the purpose of economic activity (and the role of the economist) was to “solve” the economic problem—the provision of adequate needs, opportunities, and comfort—so that the important things in life could be pursued.

But in the mania of the American housing bubble, the chase of wealth became everything. The financial sector expanded, national savings rates plunged, and Clinton-era deregulations were followed by the Bush administration’s abdication of government oversight. Financiers eagerly accepted the open invitation to recklessness and enjoyed astronomical compensation packages for embracing imprudent risks. Borrowers took on debt far beyond any responsible expectation of what they could repay. In retrospect even Alan Greenspan finally understood the errors of the era of unregulated finance he championed.

Davidson’s The Keynes Solution is half of a great book. Its first three chapters tell the “how we got here” story. They summarize clearly and convincingly the pathologies of unregulated finance, and in particular how deregulation of the banking sector skewed incentives and encouraged the chase for speculative profits via increasingly complex and innovative financial assets. Rather than concentrate on the more mundane business of traditional banking, “investors spent vast sums buying . . . mortgage-backed financial securities despite the fact that no one was sure of what actual real assets were pledged as collateral against them.” These investors don’t sound like the agents modeled on the chalkboards of the “New Classical” macroeconomists, and Davidson points out that Keynes’s theories about expectations and uncertainty capture human activity far more accurately than do hypotheses of rational expectations and efficient markets.

After this sparkling display of diagnostic analysis come two chapters of Keynesian responses to the crisis. In pitching fiscal stimulus and monetary expansion, Davidson is pushing a bit on an open door, even as he neatly links these measures back to Keynes’s analyses. But Davidson is perhaps too cavalier about the potential long-term costs of stimulus, and he dismisses the risk of inflation via an unconvincing appeal to the non-neutrality of money. It is easy to agree with his fiscal and monetary responses to the crisis: the house was on fire, and that fire had to be put out. But that does not mean there won’t be water damage to be reckoned with, and in the looming “out years,” when the economy is in recovery, inflationary pressures and burdensome debts will demand close attention.

What about the decades ahead, once recovery is achieved? Davidson advances proposals for the re-regulation and supervision of the financial sector, which follow directly and reasonably from the first part of the book. But his support for protectionist trade policies is irrelevant as a response to the current crisis and based on a very selective and distorted reading of Keynes’s positions. Davidson does a disservice to his important early arguments by spending down his own credibility.

A chapter on reforming the world’s money is truer to Keynes’s proposals for an international clearing union, and international macroeconomic imbalances were certainly an expression of problems related to the crisis. (Keynes anticipated these dilemmas and hoped a more capacious IMF might mitigate them by placing greater burdens of adjustment on creditors.) But one would have expected much more than two pages of afterthought devoted to creative, market-friendly schemes to slow the flow of speculative capital, such as a (nice, Keynesian) Tobin tax, which would inhibit counterproductive currency trades. In sum, despite the strong—if occasionally score-settling—appendix on the disappointing postwar trip from Keynes to Keynesianism, Davidson’s book limps to the finish line. A pity, as its first five chapters should be required reading.

Clarke’s Rise and Fall is also a book in two halves, but it sails upon smoother (and somewhat safer) narrative seas. The first half is a very readable biographical essay on this extraordinarily rich and full life, with an emphasis, perhaps at times excessive, on debunking various Keynesian myths inappropriately associated in the popular imagination with Keynes himself (for example, that Keynes did not mind inflation, or was always on the side of deficits). The second half reprises Clarke’s previous tracing of Keynes’ intellectual journey of the ’20s and ’30s, from a gifted and innovative but still classically trained economist into, well, Keynes: the iconic historical figure, the finished product who, having finally escaped from his classical upbringing, told fellow economist Dennis Robertson, “I am shaking myself like a dog on dry land.”

Clarke bemoans the divergence between Keynes and the Keynesians, and he tangles with Roy Harrod, Keynes’s first biographer. According to Clarke, Harrod’s The Life of John Maynard Keynes “covered up” the depth of Keynes’s opposition to conscription during the first world war and was too circumspect about aspects of his personal life (both true, but most modern Keynes biographers feel ritually compelled to critique this valuable book).

The score settling continues, as Clarke reminds (or informs) the reader that Keynes’s comment “in the long run we are all dead” has been egregiously misinterpreted. He was not devaluing the future, but rather calling attention to the fact that it could take a very long time for markets to restore equilibrium, and there would be much loss and suffering in the waiting. Similarly, Keynes was not “inconsistent,” but was admirably flexible, possessing a quality now in painfully short supply. He was open to changing his mind when the evidence suggested that he should, and to changing his policy prescriptions when circumstances demanded. Clarke also reviews Keynes’s allergy to Marxism and his “lifelong belief in the unique virtues of the market,” clearing away much of the nonsense that has been said about Keynes over the years.

In detailing the emergence of the Keynesian revolution, Clarke mines Keynes’s performance as a member of the Macmillan Committee (the formal British Government inquiry into the causes of the Great Depression), his autumn 1932 professorial lectures on “The Monetary Theory of Production,” and his vital intellectual collaborations in the 1920s and 1930s. The General Theory was published in late 1936, but by autumn of 1932, Clarke argues, “Keynes had seized upon the essentials of the theory of effective demand” —one of Keynes’s critical contributions, which holds, among other things, that downwardly spiraling consumer demand is not self-correcting and can therefore induce long economic dry spells. Reviewing the intellectual, economic, and political debates of the times, Clarke puts together the clues—uncertainty, the precariousness of knowledge, the crucial role of market sentiment—and then unmasks the killer: “Here was Keynes’ revolution,” he exclaims, “the economy was at rest. It was not self righting.”

Davidson and Clarke maintain that Keynes’s insights are necessary for understanding today’s crisis, overcoming it, and preventing its recurrence. In Skidelsky’s Return of the Master, this theme is even more explicit, and the arrows from Keynes’s theories to today’s policies are brightly drawn. This excellent, much-needed book begins with an overview and interpretation of the current crisis; then introduces Keynes, his life, and his life lessons; and concludes with what it would mean, as a practical matter, to apply Keynes’s theories.

Like Clarke, Skidelsky is keen to puncture anti-Keynesian myths (“it may surprise readers to learn that Keynes thought that government budgets should normally be in surplus”); with Davidson, he emphasizes disequilibria in the international financial economy. He endorses Davidson’s updated Keynesian scheme for an international clearing union. And with the others, Skidelsky emphasizes the central role of uncertainty in Keynes’s economics, but he gives particular attention to the philosophical foundation of the framework: the purpose of economics is to allow people to live “wisely, agreeably, and well.”

What went wrong? For Skidelsky, the deregulations, especially the elimination of Glass-Steagall, allowed commercial banks to become “highly leveraged speculators in the newly developed securities, with a hubris given by their faith in their ‘risk-management’ models.” Initially, under the guise of not playing the blame game, Skidelsky hands out a number of get-out-of-jail-free cards, absolving, at least partially, bankers, credit rating agencies, central bankers, regulators, and governments.

This magnanimity allows Skidelsky to focus on his preferred culprit: “the intellectual failure of the economics profession.” And his critique is well done. He skewers the New Keynesians for giving up the store to the New Classicals, and both for their embrace of rational expectations and the efficient-markets hypothesis.

But even if one agrees with Skidelsky, his murderer’s row of unindicted co-conspirators deserves more blame than it is assigned. Greenspan, for example, can be cited as a living embodiment of the anti-Keynesianism that caused the meltdown. In response to the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-1998—the previous crisis of unregulated capital—Greenspan’s conclusion was that “one consequence of this Asian crisis is an increasing awareness in the region that market capitalism, as practiced in the West, especially in the United States, is the superior model.”

This was wrong, but it did reflect Greenspan’s cheerleading for a deregulated financial sector that he felt no need to chaperone. Greenspan’s support also lent legitimacy to the Bush Administration’s ill-advised tax cuts, which made today’s problems worse. As Keynes wrote, “the boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury.” The budget surpluses that Bush frittered away should have been used to pay down the federal debt. Instead the debt mushroomed, making the government less able to issue the debt that is now needed.

Skidelsky does eventually come around to a bit of finger-pointing. In addition to the mistakes of economists, he identifies three broader failures: institutional, intellectual, and moral. Banks “mutated from utilities into casinos”; regulators and policymakers “succumbed to . . . the view that financial markets could not consistently misprice assets and therefore needed little regulation”; and society as a whole embraced “a thin and degraded notion of economic welfare.” Moreover, although the right emergency measures were taken to stop the economic bleeding, Skidelsky notes that little, so far, has been done to address the underlying problems. Unless we fix them, the “world is likely to limp out of this crisis to the next.”

All this sounds right. But what are the solutions? For Keynes, via Skidelsky, they start with taming (that is, re-regulating) finance, and, ambitiously, reforming the way economics is taught: decoupling the teaching of macro- from microeconomics and broadening training so that economists are once again, as Keynes described, parts “mathematician, historian, statesman and philosopher.” Is this going to happen? Skidelsky is right to doubt it, since both of his reforms take on powerful, entrenched interests and deeply rooted institutional traditions. “But it may come about gradually,” he concludes, “with the shift in power and ideas” away from the United States.

Arguably the crisis has accelerated that shift, and certainly actors in East Asia, now twice burned by unregulated finance, might be quicker to embrace Keynes. This may not offer much hope for American public policy, but it is a provocative thought.