Fixing Social Security: The Politics of Reform in a Polarized Age

Douglas Arnold

Princeton University Press, $29.95 (cloth)

The Retirement Challenge: What’s Wrong with America’s System and a Sensible Way to Fix It

Martin Neil Baily and Benjamin H. Harris

Oxford University Press, $29.95 (cloth)

Social Security is back in the news. Some Republicans are angling to reduce benefits, while Democrats are posing as the valiant saviors of the popular program. The end result, most likely, is that nothing will happen. We have seen this story before, because this is roughly where the politics of Social Security have been stuck for about forty years. It’s a problem because the system truly does need repair, and the endless conflict between debt-obsessed Republicans and stalwart Democrats will not generate the progressive reforms we need.

Social Security, believe it or not, has a utopian heart: the idea that all Americans deserve a life of dignity and public support once they become old or disabled. This vision does, for now, remain utopian: many Americans are right to worry that, without savings or private pensions, their older years will be just as precarious and austere as their younger ones. Social Security is nonetheless the lynchpin of the U.S. welfare system, such as it is. In 2022 some $1.2 trillion flowed from the system to nearly 66 million people. Most of those people are retired workers, but not all of them. Millions are the spouses or dependents of retired workers; millions more are disabled people, or the spouses or dependents of the disabled. All in all, about one in four Americans over the age of eighteen receives benefits from Social Security. If not for Social Security, almost 40 percent of older Americans would be living in poverty.

It is not going too far to say that the Social Security system, more than any other single institution, keeps the United States from becoming a truly Dickensian world of poverty and despair. Yet it has serious downsides, too. For one thing, benefits are low; even after much-needed cost-of-living increases, the average recipient will receive just over $21,000 per year. And for another, the Social Security trust fund will run dry in about twelve years, prompting an immediate benefit drop of about 20 percent (there is no realistic scenario in which benefits disappear altogether). For a middle-class family, that difference might not matter all that much, but for an elderly and disabled widow, already near the poverty line, it would be devastating.

You probably already know most of this. Indeed, it’s become conventional wisdom that the Social Security system is in trouble and shouldn’t be counted on. How many times have you heard people scoff about their Social Security taxes or warn a younger coworker their benefits will never materialize? This shrugging nihilism might make sense for the wealthier among us, many of whom are indulging in the distinctly American ritual of creating an entrepreneurial plan for our looming disability and death. But the majority of Americans don’t have 401(k)s, and many millions, especially the poor and people of color, will rely on Social Security as their main source of retirement income.

Despite this dire situation, there has not been a congressional vote, even in committee, on major reforms to Social Security since 1983. This has not been for lack of trying, at least among Democrats. In both the House and the Senate, there are serious bills, with significant support, to salvage the program. The most well-developed, known as Social Security 2100, has more than 200 cosponsors in the House. It’s an audacious bill, planning to expand Social Security benefits for the first time since the 1970s, focusing especially on the caregiving workforce. And in the Senate, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have put forth an even more ambitious plan, which would raise taxes and benefits while expanding the program’s solvency for decades.

Still, the odds of anything happening with these bills are low, at least for now. In addition to the expected Republican intransigence, Democrats themselves are not united. The relevant division is between a politics of incrementalism and a politics of bold reform and expansion. Social Security 2100 is on the less ambitious end of the spectrum, especially as it has recently been rewritten to keep Biden’s promise of not raising taxes on people making less than $400,000 per year. As such, the bill does little to address the solvency issue. The Social Security Expansion Act in the Senate is bolder and does more to address both equity and solvency—but few Democratic senators have cosponsored the bill, leaving it oceans away from the required votes.

For all their differences, these bills in the aggregate show that Social Security is perfectly capable of providing a vehicle for progressive welfare reform: any of them would do wonders, most obviously for seniors and disabled workers. But all of us, too, would benefit from knowing that something like a livable income was headed our way at the tail end of a serpentine labor market that has almost completely stopped providing traditional pensions. Despite all this, the enormous energy in recent years around expanding Medicare and Medicaid has not been matched by attention to Social Security: the politics around it have languished.

Why? One major reason is that Social Security has a marketing problem. It seems like a boring, wonky program, and one that is in any case unlikely to survive much longer. (A 2015 Gallup poll showed that more than half of Americans did not expect to receive benefits when they retired.) This situation has left the door open for conservatives, who have been baying to privatize Social Security, or at least cut benefits, since the 1970s. However impractical and unpopular this idea is, it is at least an ethos. And it has kept liberals on the defensive: again and again, they rest content by (rightly) showing that privatization would be a disaster and then insisting that Social Security can be “saved,” perhaps with some tinkering to keep it solvent.

In just the past year, as the world burned, two high-profile books on Social Security appeared. Their publication, in itself, is something of an anomaly, and I hoped that they might portend new and more exciting ways to talk about Social Security. Alas, both are both stuck in the old ways. One of them, Fixing Social Security, comes from R. Douglas Arnold, a former chair of Princeton’s political science department; the other, The Retirement Challenge, is by Martin Neil Baily and Benjamin H. Harris—high-profile economists from the Clinton and Biden administrations—and builds on a set of conferences that included some of the most respected experts on retirement financing in the country. Both books are responsible and sober guides to the issue, written by established experts who have been thinking about retirement policy for decades (all three have connections to the Brookings Institution). But both books, precisely because they insist on a politics of realism, are unrealistic and impractical. This tone of exhausted pragmatism is counterproductive, and it is beyond time to fight fire with fire.

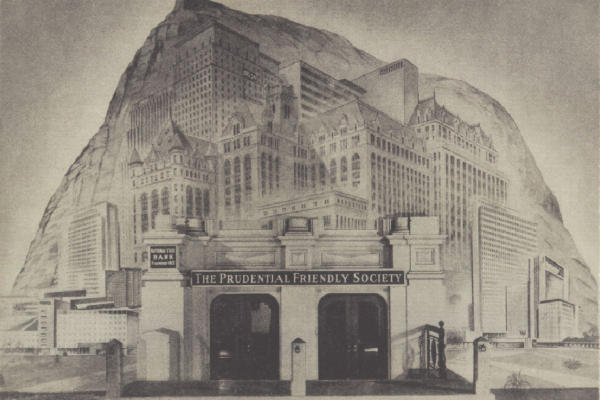

The problem is not new. Social Security was born as a moderate compromise and has never really inflamed hearts and minds. It was in fact designed from the start to fend off more radical schemes: both the Townsend Plan, which would have funneled $200 a month to every American over sixty, and the labor- and Communist-backed Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill, sponsored in 1934 by Representative Ernest Lundeen, which would have folded old-age benefits into a much broader, federally administered welfare system.

Social Security’s details have often rankled leftists, too. They have complained, justly, that the Social Security Act did a great deal to enshrine and reproduce the inequalities of race, gender, and class that structure U.S. society. For instance, many Black workers were frozen out of the program in the early years because they worked in domestic service or agriculture—two fields that were not included in the program. Women earn less than men because they move in and out of the workforce to perform care labor, which is not captured in Social Security calculations. And, most obviously, the poor themselves make less from Social Security than their richer peers, even though they need it more.

Even though the system is transparently political, in that it creates winners and losers, the Roosevelt administration labored to portray it as beyond politics. This would, they hoped, save it from being held hostage to shifts in political fortune. As such, the plan has been linked with technocrats from its origin. The original design stemmed from the Committee on Economic Security, a sort of think tank. And in the decades after its passage, the program was linked in the public eye with men like Robert Ball and Wilbur Cohen: responsible public servants, more at home with actuarial tables than with mass politics.

In the first few decades of its existence, Social Security survived perfectly well without a mass movement behind it. After all, at the time, support for Social Security was bipartisan, and between World War II and the early 1970s, both parties supported generous expansions of the program (both in the level of benefits and the number of people covered). For a brief moment, it did seem as though 1960s-style radicalism would infuse the Social Security debate, too. Jacquelyne Jackson, whom we might call a Black Power gerontologist, worked on a proposal to give Black Americans their benefits earlier to account for their lower life expectancies. Social Security, she thought, could be leveraged for anti-racism and social justice.

That moment quickly passed, and in the mid-1970s, thanks to inflation and unemployment, the program entered a fiscal crisis. Social Security has been under assault ever since, with conservatives attacking the system as fundamentally illegitimate and fiscally unsound. The classic clash, and the one we have now, has been between a GOP movement aiming to roll it back and a responsible center seeking to save it. Consider, for an early example, a 1971 debate on Social Security between Cohen and Milton Friedman. The exchange was hosted by the American Enterprise Institute, and it centered on the system’s legitimacy. Friedman was in his element: a happy warrior, making jokes and playing to the audience, even while calling for a form of privatization that would have been a death warrant for many poor and disabled people.

It is telling that Cohen served as Friedman’s opponent at all. Friedman was an ideological renegade, leading an insurgent right wing. Leftists had such figures, of course, but none of them cared much about Social Security. Cohen was the best defender the system had at the time. And he’s a good one, too: articulate and well-versed, far more than Friedman, in the minutiae of the program. He was nonetheless outmatched, and any viewer of the debate, knowing nothing about Social Security coming in, would be swayed by the smug charm of Friedman over the disheveled and frustrated bureaucrat. Cohen had nothing to combat Friedman’s rhetorical excesses, and in fact largely accepted the terms of debate. He labored to show that Social Security was compatible with “our free enterprise system.” Social Security, he insisted, “reinforces thrift, reinforces initiative.” And with some tweaks, he insisted, it could remain solvent.

The discussion has moved on, some, since the 1970s. Privatization, with some exceptions, has ceased to be a rallying cry for conservatives. George W. Bush tried to do it in his second term with disastrous results. Republicans are more likely, now, to call for benefit cuts and a higher retirement age. Democrats, for their part, are still talking like Cohen: exasperated with Republicans and claiming the moral high ground by fending off Republican cuts. That strategy, fundamentally defensive in nature, may have made sense in an era of bipartisanship and program solvency. It no longer does.

Indeed, even as the bipartisan, consensus-seeking spirit of technocracy becomes increasingly irrelevant to U.S. politics, it remains the dominant register for thinking about Social Security. Both Fixing Social Security and The Retirement Challenge exemplify this state of affairs: each presents sensible proposals to reform the retirement system, but each has an air of political unreality about it. Recognizing that Democrats as currently constituted can’t solve the matter on their own, they end up placing the onus of responsibility on the two institutions most incapable of meeting the challenge: congressional Republicans, who have lost touch with legislative reality, and the American family, already ground down by decades of austerity and wage stagnation.

The call for Republican action comes from Fixing Social Security, an excellent study of the recent history of Social Security and the reasons for Congressional inaction. Arnold has been thinking and writing about Social Security for decades, and he is a steady guide for anyone seeking to understand the system. He is rightly skeptical of privatization as a workable plan and indeed of the private retirement system as a whole. He clearly believes, too, in the legitimacy of Social Security, and in the idea that robust public support is the only way to create something approaching justice for older Americans.

Yet his political analysis remains bound by an outdated pragmatism. He convincingly argues that fixing Social Security, by which he means making it solvent, is not difficult: a series of tweaks to tax rates, retirement ages, and levels of taxable income could do it. The emotional motor of the book is Arnold’s frustration that the U.S. political system can’t deliver these reforms that are so transparently urgent and so transparently popular. (Many of the book’s pages are spent analyzing poll data to this effect.) He does call for a campaign of letter-writing and activism from the AARP. But Arnold is laser-focused on congressional politics, so he gives most of the impetus for solving the problem to Republicans. Because they avoid putting an actual policy on the table, Arnold argues, they have not been forced, as a party, to make the hard choices about taxes and benefits. Once they finally do so, the actual horse-trading with the more reasonable Democrats can begin—and, most likely, end somewhere between the modest expansion of Social Security 2100 and the modest cuts desired by many conservatives.

For all of Arnold’s policy expertise, his political analysis remains of a piece with Cohen’s: he sees Social Security as a popular, well-designed policy and is concerned that the American political system is not able to deliver the modest reforms that might keep it solvent. The Retirement Challenge, which is the end result of a star-studded set of conferences on retirement financing, shares much with Arnold’s book. Like Arnold, Baily and Harris believe in incrementalism: “if families, companies, and policymakers all took incremental steps to improve the retirement system,” they insist, “every American could achieve a more secure retirement.” This approach, they conclude, provides “the only realistic path.”

And yet, in practice, they doubt that either employers or the state will be able to do much to address the very real challenges faced by aging Americans. They hope that tax incentives might induce employers to add long-term care insurance and other similar vehicles into their benefits packages. They don’t think that private pensions can or should make a comeback, and they don’t think that the state should increase benefits, either.

So for them, the primary institution that can address the retirement challenge is the American family. The authors lean heavily on behavioral psychology to frame their questions, which basically boil down to: Why aren’t people saving more for retirement? “Some Americans,” they lament, “are myopic, focused far more on consuming today than saving for tomorrow.” And if the problem is framed primarily as psychological and individual, the solutions can be, too. Many of the ideas in this book are essentially policy incentives designed to nudge Americans into making better choices.

First, and most prominently, they expect older Americans to work. “The best way for low-wage workers to prepare for retirement,” they write, “is to work as long as they can.” They are careful to say that they don’t believe that this should be an absolute necessity. Yet they think that, for many families, it would be a good idea. Work is changing, after all, and more jobs are available for those with older bodies. They encourage Americans to find ways to transition to part-time or freelance work in old age, which would in their view both increase their health and their financial wellbeing (they even suggest that older people try becoming Uber drivers, or running Etsy shops).

In addition to working, Baily and Harris want American families to save—and to save more wisely. They advise us to continue saving a good deal more, and they hope that reforms to the tax incentive structure might help us do so. Moreover, they want families to take advantage of the private insurance market, purchasing annuities, reverse mortgages, and long-term care insurance. As they are well aware, each of these schemes has significant downsides, but they hope that with improved state regulation, they might become safe and reliable investment vehicles for American families.

These might seem like punitive measures, but The Retirement Challenge is clear that Americans should not expect much, in old age or disability, beyond a state that might keep them from dying in bitter poverty. “Anyone who has spent their career on a production line or carrying boxes,” they write, “deserves to live in retirement with an income that is at least above the poverty line.” This is not exactly stirring rhetoric. Perhaps workers like that deserve quite a bit more.

Both of these responsible and humane books thus present themselves as mainstream, common-sense analyses. Both are aware that reform is necessary to save the system and stave off a catastrophe for seniors and the disabled; both have reasonable solutions that would allow the program, in something like its current form, to remain solvent. Yet neither has a convincing political strategy. Congressional Republicans are, in all likelihood, not about to embark on a painful intra-caucus debate about how we ought to salvage Social Security. Meanwhile, American families are stretched thin as it is. If given a bewildering array of tax incentives and financial education, some of them might indeed start saving more and entering the gig economy. But surely this arrangement would also leave many people behind. This is the place where the ugly process of political negotiation might end, but certainly not where it should begin.

What explains this limited vision? The simplest diagnosis is that the authors remain stuck in the Democratic politics of Social Security as they have been since the 1930s. They want technocratic reforms; they want to work across the aisle; they want “common-sense” solutions that poll well and don’t disrupt the workings of the market. What they do not do is seek new ways to talk about Social Security, or new ways to organize around it, that might plausibly gain mass support in the twenty-first century.

Politics have moved on quite a bit since the last time Social Security was reformed in the first Reagan administration. In the wake of Black Lives Matter and COVID-19, for instance, issues of race and disability loom far larger than they did ten or twenty years ago. Each of them, too, is directly related to the politics of Social Security, yet neither looms large in these books. Neither book has any discussion of race of more than a paragraph. The authors operate in a fantasy world in which age and class, their main concerns, can be separated from race: this leads both to analytical problems, because the issues really cannot be separated, and to political problems, because there is a great deal of energy around issues of racial injustice. At the same time, the authors of both volumes pay scant attention to the issue of disability. Especially in The Retirement Challenge, the preferred solutions of Uber driving and individual saving cannot easily apply to the millions of Americans, either already old or on their way to getting old, who are disabled.

As other authors have pointed out, Social Security is essential to people of color and to the disabled, and it could thus be at the center of a political movement that took their needs seriously. To an extent, this is already happening. The bills mentioned above are seeking, in various ways, to enlarge the scope of Social Security and make it a program fit for the twenty-first century.

To make those plans a reality, we will need new ways of thinking about, and organizing around, Social Security. It is not a boring or doomed program. It is a near-utopian one, and one that could very well be the beating heart of a grayer and more caring America in the latter half of the twenty-first century. Time, though, is not our ally. Every year it will become more challenging to expand the system while also solving the solvency crisis. And every time that Social Security makes its way into the news is an opportunity to push for a better and more inclusive form of Social Security: one that rewards caregivers, expands benefits, and provides something like an American dream worthy of the name.

We’re interested in what you think. Send a letter to the editors at letters@bostonreview.net. Boston Review is nonprofit, paywall-free, and reader-funded. To support work like this, please donate here.