Among the commentaries that most dramatically frame the tension between law and justice are Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail” (1963), one of the most celebrated writings of the Second Reconstruction, and subsequent critiques by jurists, most notably future Supreme Court Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr.’s “A Lawyer Looks at Civil Disobedience” (1966).

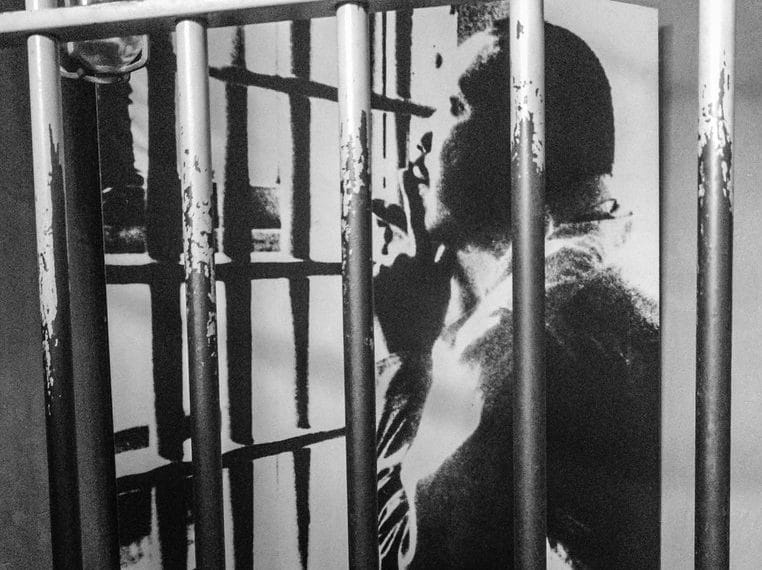

King composed “Letter From Birmingham Jail” while imprisoned for leading a demonstration in defiance of an injunction in Birmingham, Alabama on Good Friday 1963. He wrote it over the course of a week, scribbling on whatever scraps of paper he could scrounge before handing the notes to his lawyers for a secretary to type them out. Drafts would then be sent back to King for revision and supplementation.

The letter responded to a statement by eight white clergymen published in January 1963. With school desegregation rulings looming, the eight men had urged white people to eschew protest in the street and instead take their complaints to court. Three months later, in the midst of King-led demonstrations, they wrote again, this time criticizing “a series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders. We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.” In their view, segregation in Birmingham could be best addressed by “citizens of our own metropolitan area, white and Negro, meeting with their knowledge and experience of the local situation.” Again the clergy urged dissatisfied parties to bring their cause to the courts and to forgo protests. “We appeal to both our white and Negro citizenry,” the eight proclaimed, “to observe the principles of law and order and common sense.”

King’s response was not wholly spontaneous. The year before, the New York Albany News had solicited a letter from him during his jailing in Albany, Georgia. Prior to that he had considered publicly rebuking southern white moderate religious leaders. In Birmingham, facing censure from white clergy, King finally delivered that rebuke. Featuring the logic and rhetorical moves of a well-written brief, the letter repeatedly disputes the accuracy of King’s adversaries. He maintains that, even if their claims had been accurate, their arguments would still be deficient.

First, King denies their charge that he is an interloper, pointing out that his Southern Christian Leadership Conference had a Birmingham affiliate and that, indeed, the head of that affiliate, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, had invited King to town. More fundamentally, however, King challenges the insider-outsider dichotomy. “I am in Birmingham,” King wrote because “injustice is here” and “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

King similarly challenges the accuracy of the clergymen’s contrast between his purportedly extreme conduct and the putatively restrained behavior of city officials, including the police. Elaborating on why the contrast “profoundly” troubles him, King responds

I doubt that you would have so warmly commended the police force if you had seen its dogs sinking their teeth into unarmed, nonviolent Negroes. I doubt that you would so quickly commend the policemen if you were to observe their ugly and inhumane treatment of Negroes here in the city jail; if you were to watch them push and curse old Negro women and young Negro girls; if you were to see them slap and kick old Negro men and young boys; if you were to observe them, as they did on two occasions, refuse to give us food because we wanted to sing our grace together. I cannot join you in your praise of the Birmingham police department.

King asserts as well that he, Reverend Shuttlesworth, and other activists had negotiated in good faith with public and private authorities in Birmingham only to see agreements betrayed.

More importantly King challenges the premise that “frustrations” and “discontent” are necessarily bad, and that “extremism” is a vice. He insists that the social unrest that so perturbed the eight clergymen should have been seen as a hopeful sign—that long-oppressed Black people were challenging their subordinated status. “[T]he present tension in the South,” King contends, “is a necessary phase of the transition from an obnoxious negative peace, in which the Negro passively accepted his unjust plight, to a substantive and positive peace, in which all men will respect the dignity and worth of human personality.”

As for the allegation that the SCLC’s disruptive demonstrations constituted “extreme” measures, King boldly adopts the charge:

Was not Jesus an extremist for love . . . Was not Amos an extremist for justice . . . Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel . . . So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. . . . [T]he nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists.

Having addressed critics’ complaints, King sets forth some of his own, focusing on the white “moderate” as the obstacle to racial justice:

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice . . . who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action” . . . who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.”

Even more disappointing, King maintains, was the white ministerial moderate. Having hoped that Southern white ministers, priests, and rabbis would be among his staunchest allies, King found that “some have been outright opponents” and that “all too many others have been more cautious than courageous,” remaining “silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained glass windows.”

Singling out a term—“law and order”—that would gain significance in the sixties and after, King writes that he “had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice.” When law fails to be just, King declares, it may be properly and non-violently defied. “I would agree with St. Augustine,” he avers, “that ‘an unjust law is no law at all.’”

A just law, he writes, “is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. . . . Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.” According to King, “[a]ll segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority.” Seeking to sharpen the distinction, King suggests two tell-tale indicia of legal immorality. One is that unjust laws typically entail “a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself.” A second is that unjust laws typically entail a code “inflicted on a minority that, as a result of being denied the right to vote, had no part in enacting or devising.”

Finally, King insists on distinguishing his disobedience of law from that of his antagonists: “In no sense do I advocate evading or defying the law, as would the rabid segregationist. That would lead to anarchy. One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty.”

This essay is featured in Rethinking Law.

King maintains that his precepts evinced reverence for acceptable law properly understood: a person “who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.”

Four years after King wrote “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” the Supreme Court of the United States upheld King’s conviction for contempt of court even if the injunction he violated was itself illegal. When Justice Potter Stewart quipped in the case, Walker v. City of Birmingham, that “respect for judicial process is a small price to pay for the civilizing hand of law,” he sided with those who feared that protest had gotten out of hand; who believed that assertions of individual conscience had degenerated into egotistical pretensions; who held that loose talk of civil disobedience threatened to unloose chaos and that attraction to King and sympathy for the sufferings of African Americans had tempted all too many to abandon conventional sound habits that are crucial to stability in a large, complex, conflicted polity.

Scores of observers echoed these beliefs. One was Morris I. Leibman, a major figure in the Chicago bar, who in 1964, as chair of the American Bar Association Standing Committee on Education Against Communism, delivered an address pointedly titled “Civil Disobedience: A Threat to Our Law Society.” Concerned about communist exploitation of racial conflict, Leibman insisted that “[n]ever in the history of mankind have so many lived so freely, so rightfully, so humanely.” Our “imperfections,” he declared, “do not justify tearing down the structures which have given us our progress.” Challenging two rallying cries he associated with the Black freedom movement, Leibman excoriated “Freedom Now” and “righteous Civil Disobedience.” The former, he charged, was a dangerous delusion: “The cry for immediacy is the cry for impossibility. It is a cry without memory or perspective. Immediacy is impossible in a society of human beings. What is possible is to continue patiently to build the structures that permit the development of better justice.”

Leibman then declared that “[t]he concept of righteous civil disobedience . . . is incompatible with . . . the American legal system.” Our grievances, he insisted, “must be settled in the courts and not in the streets.”

In “Civil Rights – Yes; Civil Disobedience – No (A Reply to Dr. Martin Luther King),” Louis Waldman, a liberal attorney, maintains that those who appeal to the legal system for relief against mistreatment “cannot say that they will abide by those laws which they think are just and refuse to abide by those laws which they think are unjust. And the same is true of decisions on constitutional principles.” Contrary doctrine, Waldman declares, not only veers into illegality, but is also “immoral, destructive of the principles of democratic government, and a danger to the very civil rights Dr. King seeks to promote.” According to Waldman, it was time for the organized bar to “tell Dr. King and his devotees of civil disobedience that the rule of law will and must prevail, that violators of the law, however lofty their aims . . . are not above the law.”

Lewis F. Powell, Jr., president of the American Bar Association in 1964-65, offered consequential contribution to this camp of criticism. In a lecture delivered at the Washington and Lee University School of Law in April 1966, Powell confronted what he termed the “heresy” of civil disobedience, the notion that “some laws are ‘just’ and others ‘unjust;’ that each person may determine for himself, in accordance with his own conscience, which laws are ‘unjust;’ that each is free to violate the ‘unjust’ laws – provided he does do peacefully.”

Powell expresses disappointment with what he perceives as the bar’s complacency in the face of a dangerous provocation. “One would have supposed,” he declares, “that lawyers . . . the guardians of our legal system, would have rallied promptly to denounce civil disobedience as fundamentally inconsistent with the rule of law.” Instead, “most lawyers have remained silent,” while “a surprising number have written in justification.”

Powell—a southern moderate—writes that he appreciated “the deep emotions engendered by the civil rights movement.” After all,

the Negro has had, until recent years, little reason to respect the law. The entire legal process, from the police and sheriff to the citizens who serve on juries, has too often applied a double standard of justice. Even some of the courts at lower levels have failed to administer equal justice. Although by no means confined to the southern states, these conditions . . . have been a way of life in some parts of the South. Many lawyers, conforming to the mores of their communities, have generally tolerated all of this, often with little consciousness of their duty as officers of the courts. And when lawyers have been needed to represent defendants in civil rights cases, far too few have responded.

There were also the discriminatory state and local laws, the denial of voting rights, and the absence of economic and educational opportunity for the Negro. Finally, there was the small and depraved minority which resorted to physical violence and intimidation.

These conditions, Powell acknowledges, “have sullied our proud boast of equal justice under law.” They “set the stage for the civil rights movement.” They account, in large part, for why King’s call for civil disobedience resonated so widely. Still, notwithstanding these extenuating circumstances, the heresy of civil disobedience, Powell warns, could in the end produce “even greater injustice” than the evil of white supremacism.

Powell’s critique rests on three points. First, while flawed, U.S. democracy is sufficiently inclusive and regenerative to nullify rightly calls for revolution. “[D]espite some conditions of injustice” in America, Powell contends, “wrongs can be and ultimately are redressed in the courts, the legislatures and through other established political institutions.”

Second, Powell stresses that the appeal to transcendental values above “mere” law—the appeal to “natural law,” “God’s law,” and “Justice”—was by no means accessible only to those whose ends one might find appealing. Segregationists, too, could make appeals to their version of God’s law. Borrowing from a colleague, Powell writes that “[i]f the decision to break the law really turns on individual conscience, it is hard to see in law how Dr. King is any better off than former Governor Ross Barnett of Mississippi, who also believed deeply in his cause and was willing to go to jail.”

Third, Powell argues that civil disobedience ultimately undermined the Black freedom struggle. Though he concedes that civil disobedience might sometimes accelerate the pace of reform, he argues that its costs would generally outpace its benefits “in terms of racial bitterness and discord, and particularly in the . . . lawlessness . . . which the doctrine of disobedience has encouraged.” Echoing King’s commitment to non-violence, Powell insists that worthy ends “can never justify resort to unlawful means.”

What is to be said about this colloquy between King and Powell?

More than many of King’s detractors, Powell acknowledges some of the gross injustices to which King alludes in his letter. One looks in vain, however, for a speech or article by Powell dedicated principally to repudiating white supremacism. His critique of evasion and defiance of the law by segregationists is sharp but ultimately parenthetical. It occupies a couple of paragraphs that are swallowed up by his main concern: rejecting King’s justification for extra-legal resistance to the racist status quo. As between the imperative to challenge racial oppression and perceived deficiencies of anti-racist protest, the latter most firmly gripped Powell’s attention.

Powell had had ample opportunity to condemn segregation and other manifestations of racial mistreatment. He was a lawyer-statesman with national prominence; served as Chair of the Richmond School Board between 1952 and 1961 and President of the American Bar Association; he could be loudly insistent on many topics. In condemning white supremacism, however, Powell was diffident. While he noted for example, that Southern legislatures and officials may have disobeyed the law first by refusing court-ordered school integration, this observation is merely a momentary digression. Powell’s main point was that the United States, for all its flaws, is a democracy that morally warranted obedience from all its citizens, including Negroes.

King did not dispute that point. He, too, pledged fealty to the United Stated; he displayed his devotedness by insisting upon accepting punishment for disobedience. Like Powell, King was a thoroughgoing patriot. Unlike King, however, Powell was not an impassioned enemy of racial oppression. He was, at most, a reserved adversary, condemning some of white supremacism’s most obvious manifestations. But he did not seem to appreciate the breadth, depth, and destructiveness of racial oppression. One might not pick up from Powell’s article, for example, that at the very moment of its publication, the Commonwealth of Virginia continued to punish marriage across the race line as a felony. What most stirred Powell was not the persistence of racism embodied in law, but perceived deficiencies in the thinking of racial dissidents. The lawyer’s thinking reflected the sensibility that King directly chastises in his Letter—the impulse of the white moderate “who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice,” and “who constantly says: ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek [but not your methods of direct action].”

Powell charges King with offering little in his letter that distinguished “good” from “bad” law other than subjective preferences. Echoing Justice Hugo Black, Powell argues that it would be better for the country and Black America for racial justice activists to entrust their demands to democratically sanctioned legal procedures than ad hoc dramatizations on the streets. Further echoing Justice Black, Powell warns that the inclination to act as one pleases, notwithstanding law, would be considerably strengthened by applause for appeals to sources above legality.

“A Lawyer Looks at Civil Disobedience” reflects King’s success, at least partially, in persuading Powell that the Jim Crow regime was morally rotten and that the rottenness reached deep into the ranks of the bar. Powell draws the line, however, at thought and conduct that repudiated key tenets of a legal regime that, to him, was flawed but essentially good. Powell never questions the ability of U.S. courts, laws, and political institutions to serve justice, and he argues that “due process and democratic procedures, even though painfully slow at times, are a far more dependable and certainly less dangerous means of correcting injustice and solving social problems” than acceding to ad hoc demands backed up by threats of civil disobedience.

Interestingly, despite Powell’s rejection of King’s argument for basing action in a “higher moral law,” the protests that King’s movement undertook did not, for the most part, defy federal law. Many observers associate the theory of civil disobedience that King advanced in the Letter with the whole of direct action by the civil rights movement. Burke Marshall usefully noted, however, that racial dissidents defying Jim Crowism after 1954 most often were acting not against, but with, the law. They may have defied local segregationist ordinances, but they were typically doing so with the backing of a superior legal authority— the federal Constitution. There were many sit-in arrests, for example. But convictions were often annulled when appellate courts held that, under federal constitutional laws, local police had acted wrongly. The protest program, Marshall observes, typically “involved nothing that was illegal in an ultimate sense.” True, participants expected that they would be arrested and jailed. But they expected this not because they intended to break any constitutional laws. They usually acted under a claim of federal constitutional right, and their legal prognosis was often proven correct.

Indeed, in his first major address as a civil rights leader, the extemporaneous sermon on December 5, 1955 in which he announced the Montgomery Bus Boycott, King appealed to the Constitution in understanding the difference between just and unjust actions. He remarked:

My friends, don’t let anybody make us feel that we are to be compared in our actions with the Ku Klux Klan or with the White Citizens Council. There will be no crosses burned at any bus stops in Montgomery. There will be no white persons pulled out of their homes and taken out on some distant road and lynched for not cooperating.

He went on to say that “there will be nobody . . . among us who will stand up and defy the Constitution of this nation.” What seems to have emboldened him to make such a claim was a perception of the Constitution as some sort of holy writ. “[W]e are not wrong in what we are doing,” King asserted. “If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong.”

Eight years later, when writing “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King avoided resting his case on the federal Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court. Although he had typically deferred to what lawyers posited as the legal boundaries within which he could act, in Birmingham (as on several other occasions), he disregarded attorneys and was prepared to violate injunctions in accord with what he perceived to be “higher moral law.” In jail, with the time and solitude needed to produce his defense of civil disobedience, King attended to the chore of distinguishing what makes a higher law, and why the character of his protest differs from that of white supremacists. He did not repeat his earlier suggestion that the Constitution was touched by divinity. Rather, he rested his case squarely on the proposition that he was morally entitled to disregard immoral law, to act against a law that “conscience tells him” is unjust.

Despite King’s efforts, however, he could not accomplish what scores of philosophers and theologians have also failed to—creating a consensus metric by which to distinguish moral from immoral law in a large, diverse, and polarized society. King could not escape the reality that his distinction between just and unjust laws was ineluctably controversial. Powell was correct to note the danger that King’s certitude posed: Governor Ross Barnett, a devout, church-going, Christian segregationist was also filled with certitude.

King, however, rightly recognized the universal need for an appeal to authority that transcends the established norms of government. As he observed, the atrocities that Hitler committed were “legal” under the laws of the Third Reich. King had the moral high ground, but he and Powell had latched on to different horns of an unresolved and unsolvable dilemma.