As I write this post, it has been about three weeks since Thomas Duncan was diagnosed with Ebola in Texas. The media and political hysteria that has ensued in this country is amazing, statistically and historically. Unlike, say, tuberculosis or the flu, it is extremely hard to get infected with Ebola unless one is caring, without adequate protection, for an actively ill patient. Consider that none of the people who were living with Duncan show symptoms.

One person, Duncan himself, has died from Ebola in the United States in these three weeks. In contrast, during an average three-week period in the United States: 35 people die from tuberculosis; 3,200 from influenza and pneumonia (500 of those people under 65 years of age); 1,100 from suicide by gun; 650 from homicide by gun; 1,000 by alcoholic cirrhosis; and 1,900 by motor vehicle accident.[1] These deaths are not only vastly more numerous, they are much more contagious, either in a medical sense or in a sociological sense. Where are screaming headlines for those risks?

So much for the statistics. From an historical view, there was a time when alarm, even a run-to-the-hills psychology, made sense in reaction to a disease appearing on our shores. We do not live in such times now.[2]

Understandable Fear

In the summers of the 1790s, when yellow fever—spread by mosquitoes, but who knew?—swept through Philadelphia, elites, including new President George Washington in 1793, fled upland to the village of Germantown. Absent an understanding of the disease, fleeing made sense. Over those years, the village developed as a summer retreat to escape disease and then later a year-round town.

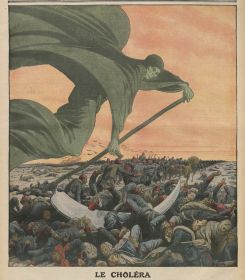

In 1832, residents of Schenectady noted reports of cholera in England and its arrival in downstate New York and then tracked its advance upstate. Understanding little about cholera—typically transmitted by drinking water contaminated by human feces with the bacteria, but who knew?—civic leaders mobilized citizens to clean the streets, experiment with chlorine or vinegar disinfectants, reform their personal habits, and join in prayer. In the end, forty out of the town’s 5,000 residents died. New York City, further south, suffered far worse. Tens of thousands of the well-to-do fled Manhattan. “The roads, in all directions, were lined with well-filled stagecoaches, livery coaches, private vehicles, and equestrians, all panic-struck, fleeing the city” and filling up farm homes for miles around. Over 3,500 of those who did not or could not flee, largely poor, immigrant, and black New Yorkers, died. On the Illinois frontier, federal troops carried cholera into communities which were already beset by seasonal epidemics. The cholera epidemic lasted there into 1834; deaths mounted so rapidly that sometimes two bodies shared a blanket for a coffin.

Controlling Fear

Over the next sixty-plus years, the threats diminished. Helped by an emerging understanding of disease, local governments developed public sanitation. They built or expanded water-delivery systems, sewer complexes, and waste-treatment facilities; purified drinking water; drained stagnant pools to rid mosquitoes; and cleaned the streets of offal and ordure. As always, some residents benefited before others, but eventually the projects vastly reduced water- and waste-borne bacteria for virtually all townspeople.

These public initiatives, along with improving personal hygiene and sanitation, sharply reduced the toll of epidemics. In 1892, cholera once again arrived in New York City; it had already killed many thousands in Europe and dozens of passengers on arriving ships. The city’s health authorities quickly diagnosed the disease, quarantined the ill, disinfected homes, and cleaned the streets. In the end, only nine New Yorkers died. Epidemics did not disappear—the 1918–19 influenza pandemic took about 500 lives in Schenectady alone, 500,000 or more in the nation—but overall death rates from infectious diseases, especially for the youngest, dropped substantially. Even the AIDS epidemic has been, by historical standards, a minor killer. In 1900, about one of every 500 Americans died of tuberculosis; by the end of the century only about one of 6,000 Americans was even diagnosed with AIDS.

The historical lessons here are that, while alarm and drastic emergency actions are needed in a few West African countries, the United States has the expertise and the resources to contain this kind of infectious disease. Whether we have the same—and whether we have the will—to contain the much greater killers like alcoholism, firearm use, and motor vehicles is another story.

Notes

[1] Calculated from 2011 mortality statistics here (pdf).

[2] This post largely draws on Ch. 2 of Made in America. The Germantown story can be found in Wolf, Urban Village, and the Schenectady story in Wells, Facing the ‘King of Terrors.’

(Re-posted on The Berkeley Blog on October 22, 2014.)