Three days after Mrs. Peete’s one-eyed dog, Gnarls Barkley, was run over by a 2002 Goodyear Tire, Linden Robbins buried her fingers in the fresh-turned dirt of the mutt’s grave and tried to raise him from the dead. She felt the dog’s bones tremble underneath the soil and smiled. She was violently whispering a string of low vowels when Mrs. Peete found her kneeling in the backyard.

“What in God’s name are you doing out there, girl?” Mrs. Peete was from the back corners of Alabama and her southern growl perked Linden’s ears and sliced the string of sounds from her lips. The vowels seeped into the dirt and fell on the wooden box like confetti.

She quickly got to her feet, apologizing. “I was just talking to Gnarls Barkley, Mrs. Peete.”

Linden tucked the heavy book under her arm and tried to forget the feeling of the dog’s bones trembling in the soil under her hands.

Mrs. Peete rolled up her doughy shoulders and pursed her lips. She was a large woman, standing nearly six feet tall with cantaloupe-sized calve muscles, toned from carrying around her thick frame. Linden knew that each afternoon Mrs. Peete mixed a thick lather of coconut oil and avocado in a small jar before smearing the mixture on her hair and twisting a towel atop her head. Linden liked this about Mrs. Peete. It was consistent and Linden liked things like that.

“What you got there?” Mrs. Peete asked her, nodding toward the book that was lying open on the ground.

Linden scrambled to pick it up. “Just a book my grandmother gave to me, Mrs. Peete.” It was St. Augustine’s Book to Raise the Dead and Linden had gotten it from her grandmother two weeks after she and her mother had moved 942 miles from Highland Park, Illinois, to Amherst, Massachusetts, where they lived in a green house with yellow shutters 2,032 miles from her father who lived in a blue house with a dog named Ranger and worked in a building with 36 floors. Linden knew this was true because of the postcards her dad sent her on the third Saturday of every month.

Linden watched Mrs. Peete wipe her forehead with the back of her hand before saying, “You just go on home, honey. Gnarls Barkley is running up and down that rainbow bridge as happy as can be right now. You best be getting to bed before your momma starts worrying.”

Linden tucked the heavy book under her arm and tried to forget the feeling of the dog’s bones trembling in the soil under her hands. It gave her the jeebies and she wiped her palms on the front of her shirt before waving to Mrs. Peete as she walked away, the ghost of Gnarls Barkley nipping wildly at her heels.

• • •

The first time Charlotte watched Linden, she walked through the house delicately, like a cat learning the lines of one room before moving onto the next. Charlotte always spent the most time in the bathroom. She liked to test the toilet first, see how it flushed, watch the water gurgle down the drain before refilling. Then she moved to the closets. Charlotte didn’t like surprises and she liked to make sure she knew the hidden places of the house, the bones, the bends in the elbows, the places where lint got trapped.

Charlotte never cared much for children. But Sivvy Robbins paid well and there were things about Linden that she found intriguing. She was peculiar, but in a shy way, spending her time memorizing facts and sorting crayons into color categories. She also had severe allergies. There was a list on the refrigerator of all the foods she couldn’t have. Chocolate, coconut oil, pineapple, flaxseed, corn, mushrooms, almonds, red wine vinegar, blueberries, caramel. Charlotte didn’t pay much attention to the items. She looked over the list only once and paused when she saw that Linden was allergic to raspberries. Emily Dickinson was also allergic to the tart fruit and she felt a pang of envy that the girl had something in common with the poet. The list was ordered according to severity with a star by the items that would make Linden stop breathing. Raspberries was accompanied by the note “Rash.”

Charlotte had been babysitting Linden for almost a year when she first heard the girl talk about the ghost of a dog that followed her around.

Once, when Charlotte was feeling particularly irritated with the girl, she brought a carton of raspberries with her. She hid them in her purse so Linden wouldn’t see. The girl was very observant. That night, while stirring a glass of lemonade for Linden, she cut a raspberry in half and dropped it in. Just to see. She watched Linden drink the lemonade in three thick, childish gulps and waited. Within ten minutes, a constellation of red bumps had appeared on her neck, her thin fingernails scratching fiercely at her skin. Charlotte swabbed at the irritated flesh with the cream in the medicine cabinet and wondered what the rash would look like on Dickinson. After she put Linden to bed, she stood in front of the bathroom mirror and scratched her own neck until the skin reddened and burned. She twisted her hair into a tight bun and pursed her lips. She imagined this was how Dickinson would look if she studied her own refection in the mirror. When the rash began to fade, Charlotte rubbed the skin until it bled. Until she was certain it would leave a scar.

• • •

Charlotte had been babysitting Linden for almost a year when she first heard the girl talk about the ghost of a dog that followed her around. “The school counselor says he is a product of the divorce,” Linden’s mother, Sivvy, told Charlotte. “It’s been over a year now, but I guess these things can manifest. That’s what the counselor says.” Charlotte could see the faint pink of lipstick on Sivvy’s teeth as she sighed. “I know she’s been through a lot with her dad moving so far away and with us moving back to Massachusetts.”

Charlotte hated when people said they had been through a lot. Linden never had to watch her brother play too close to the edge of the river. She never had to plug her ears when she heard the sound of a faucet being turned on because she couldn’t stand the sound of running water. She never had to read five hundred poems to drown out the sound of her brother’s scream, the only sound she heard before the water filled his lungs. She never had to see the way her brother’s face looked, hollow and white, as it floated down the river. Linden Robbins, a ten-year-old girl obsessed with colors and facts, who had moved two thousand miles away from her father, had not been through a lot.

“If she talks about Gnarls Barkley, just remind her that the dog is dead and she needs to quit pretending otherwise,” Sivvy told Charlotte. “I don’t want her to be bothered at school any more than she already is.”

Charlotte didn’t understand Sivvy. When the woman hired her, she thought it was out of sympathy, a weak apology to her aunt who was excluded from most of the women’s social engagements. Now she wasn’t so sure.

“I’ll remind her, Ms. Robbins,” Charlotte answered, trying to ignore the way her fingers had begun to tingle and her eyes itch when she heard about Linden’s new obsession.

Charlotte found Linden sitting on the chair in the living room. Her feet were curled under her small body and she squinted under thick glasses as she balanced an open book on her knees. Charlotte perched on the edge of the footstool.

Linden looked up but didn’t say anything. She was a quiet child and Charlotte knew that she could go an entire evening without saying a single word. She just watched. Waited.

“I heard about Gnarls Barkley,” Charlotte said.

“I’m not supposed to talk about him.” Linden’s voice was lower than a normal child’s and it always took Charlotte by surprise when she heard it.

She bit the inside of her cheek. “You can talk about him with me.” Over the past year, Charlotte and Linden had come to an unspoken understanding, the kind that comes from a mutual disdain of putting up a façade. It wasn’t that Charlotte and Linden disliked one another, it was just that they didn’t need each other. Charlotte understood that she was staying at the Robbinses’ because it made Sivvy feel like a good mother, and Linden understood that someone had to be there in case she had an incident. In that way, Charlotte and Linden respected one another in the way most adults are unable to. Now, telling Linden she could confide in her, Charlotte knew that the unspoken agreement had been slanted and she waited anxiously to see what the girl would do.

Linden was silent.

Linden could always tell when a person had seen death. They walked differently, cautiously.

Charlotte licked her lips. “Is he here now?” she asked.

“You’re sitting on his tail.” Linden blinked, her voice deadpan.

Charlotte quickly stood. “Damn ghost,” she mumbled and then smiled when she saw Linden watching her. For a moment she thought she saw the faint shadow of a smirk on the girl’s lips. “I believe you,” Charlotte said. “I believe that Gnarls Barkley is sitting there. I believe that you raised him from the dead.”

“I do, too.”

Charlotte shifted her weight from one foot to the other. “Linden,” she paused. “Do you think you could do it again?”

• • •

Linden had heard the stories about Charlotte. She knew that she had once had a brother but he died one day in the water. Charlotte had been there. She had been seven years old. Linden learned the story through bits and pieces. From Mrs. Lucas, she learned that Charlotte and her brother had been playing in the river. It was Betty Lianus who said that the rains had been bad that year and the water was higher and wilder than usual. Linden heard from Susan Perkins that Charlotte had seen her brother go too far into the river, probably to catch a turtle or frog. The current was just too strong, they all whispered as if saying it quietly would keep the water tame.

Linden could always tell when a person had seen death. They walked differently, cautiously. They had a darkness in their eyes as if the ghost of the dead cast shadows under their irises forcing them to see the world through a foggy film. Linden didn’t understand a lot of things about Charlotte, but she understood that she was shadowed by the ghost of her dead brother and he followed her around like a dog nipping incessantly at her heels.

• • •

Charlotte had been a tour guide at the Emily Dickinson museum for the six months. At sixteen, she was the youngest guide to ever have worked in the historical house. Mrs. Jones, the manager of the museum, hired Charlotte after the girl had spent every afternoon joining tour groups as they were ushered through the home, and evenings leaning against the tall oak outside, quietly reading poetry until the light gave out. The museum was inside of the Dickinson’s homestead. The eleven-room home was furnished with many of the family’s original possessions, but only three rooms were open to the public. The others were under renovation, the tour guides told the guests. It was partially true. There is only so much history to reveal before people get overwhelmed. Charlotte liked that. She liked that she was one of the only people who could open every door, step on every plank, leave her fingerprints on every wall.

Last month Mrs. Jones gave Charlotte a key to the house. To open and close the museum, the manager said. That night, Charlotte waited until it got dark before she walked to Main Street and opened the door to the Dickinson home. It was noisier than she thought it would be. The hinges creaked and the windowpanes rattled as she walked from room to room. Just to see. The library was her favorite. She sat at the desk where Emily Dickinson wrote her poems and opened one of the heavy books from the shelf lining the wall. She smelled the pages and wondered if some piece of the poet was stuck in the binding. A hair follicle, a piece of skin, a fingernail. She inhaled deeply and swallowed.

When she had filled her body with as many breaths as it could hold, Charlotte put everything back in place. She was meticulous. Precise. Then she locked the door and ran into the night, her body heavier than before.

• • •

She sat at the desk where Emily Dickinson wrote and opened a heavy book. She smelled the pages and wondered if some piece of the poet was stuck in the binding.

The air was calm when Charlotte took Linden to the museum. Linden had seen the house before, but at night the moon cast a dim glow on the yellow paint and four white pillars guarding the door. Linden felt her heartbeat quicken and she reached a hand into her coat pocket, searching for the pair of dice she carried. They were a gift from her father and the sound of their rattle kept her calm. She shook them quickly and felt her stomach quiet. She clutched St. Augustine’s Guide to Raising the Dead against her chest.

“Did you know that 150,000 people die each day?” she asked Charlotte.

“Death is a part of life,” Charlotte recited before walking up to the front porch.

“Wait,” Linden said. “We first need to create a scenario.” She knelt on the ground and opened the book. The pages were covered in inked calligraphy.

“The book says that we need to create an environment that the dead would want to come back to.” Linden used her finger to underline the words as she read them. She looked up. “When I rose Gnarls Barkley from the dead, I reminded him of all the fun he had here on earth. I started with his yard and told him about playing fetch and chasing Mr. Finn’s old cat.”

When Charlotte didn’t respond, Linden looked up. “Why would Emily Dickinson want to come back to this place?” she asked.

Charlotte was quiet for a moment. Her eyes, unblinking, stared at the red and yellow pansies circling the house. “Emily loved to garden,” she said. “She used to come out here every morning before the sun came up.” Charlotte licked her lips. “She wouldn’t even change out of her nightdress. It was white once, but the dirt had stained it over the years. In her nightgown, she would kneel on the ground and pull weeds, trim bushes, plant daisies until she could hear the pedals of the milkman’s bicycle. They were louder than the chime of the glasses tapping each other in the basket.” Charlotte paused and cocked her head. “Do you hear that?” she asked.

Linden looked over her shoulders. The way Charlotte’s voice sounded gave her the jeebies and she reached for the dice once again, rubbing the smooth cubes between her fingers.

“There was a vegetable garden over here.” Charlotte stood and walked to a large square of dirt to the left of the front porch. “It was her mother’s, really. But, after her mother died, Emily was the one who kept it up.”

Linden watched her bend down and bury her fingers into the soil. “The peppers used to grow right here,” she said. “Emily’s mother grew them for her husband. The red ones were his favorite.” Charlotte paused and her brow furrowed. “I don’t remember where I learned that,” she said. She looked down at her hands covered with dirt before turning toward Linden.

“Let’s go inside,” she told her. Then Charlotte brought her finger to her mouth and sucked off the dirt.

• • •

Linden didn’t understand death and, because she did not understand it, she was fascinated by it. She didn’t understand the difference between being dead and being gone, gone, gone. Her father wasn’t dead, but he wasn’t in Amherst. He was in a town she had never been to with a dog she had never met.

When her grandmother had given her St. Augustine’s Book to Raise the Dead, she devoured the pages with an instinctual hunger. Her body was more than ready to test out the practice when Gnarls Barkley was found dead in the street. Linden never believed that the spell could work and was more than a little surprised to see the ghost of the dog following her home. At first he would just sit and watch her. He followed her into the bedroom and sat by the door as she tried on clothes and looked through her pin collection. Then, over the days, he began to move closer until he followed at her heel.

“Did you know that 150,000 people die each day?” she asked Charlotte.

The first time she touched him he bit at her hand. She flapped her hands by her ears and touched him again. This time he let her and she wondered at the softness of his fur. It was almost silky. Nothing like the rough matted coat he had had before he was run over. She could see him clearly, though others could not, but the lines of his body were blurred at the edges. It was as if someone had colored him in with pencil and then run their hand over the page. She thought his body would be cold but it wasn’t, not hot either, and when he curled up beside her and pressed his body against her leg, she felt only the slight pressure of something there. And it was a comfort.

• • •

The living room was the first place on the tour, Charlotte said. It was smaller than Linden thought it would be and it smelled like stale perfume. There was a piano against the wall and Linden tapped the keys lightly, lightly, lightly.

“Stop that,” Charlotte hissed. “Don’t touch anything.” She smacked the back of the girl’s hand and Linden rattled the dice in her pocket. There was a green velvet sofa on the opposite side of the room and she sat down with the book. It felt heavier than it did in Mrs. Peete’s backyard. Gnarls Barkley hopped up beside her and laid his head on her lap. She stroked his head tenderly.

“Emily Dickinson’s father was a businessman. He wasn’t home much.” Charlotte studied the portrait of the family hanging on the wall. “When he died in a wagon accident, the family filled in his absence in different ways. Her mother began to can fruit. Emily’s sister, Lavinia, sewed. She was always good with a needle, but, after her father’s death, she began to work with yarn and fabric. And Emily’s brother. . . .” Charlotte paused as if the word was almost too big for her mouth and had trouble falling from her lips. “He. . . .” she tilted her head to the side. “He began to play by the river.”

Linden cocked her head and Gnarls Barkley’s ear perked. She clutched the dice in her hand. “But there isn’t a river around here,” she said.

Charlotte was quiet. “No.” she shook her head. “I must have the facts wrong.”

Linden stopped petting the dog. “And what did Emily do?” she asked.

Charlotte looked at her. “She began to write poetry.”

• • •

Their first attempt to raise Emily Dickinson from the dead was in the library.

Their first attempt to raise Emily Dickinson from the dead was in the library. Charlotte told Linden that that was the poet’s favorite place. It was where she did all of her writing. Linden and Charlotte sat on the floor as Gnarls Barkley circled the room, eagerly sniffing the cracks in the wall. The air was colder there and Linden shivered.

“Tell me about the people who lived in this house,” she told Charlotte. She noticed Charlotte’s face had paled and her nails looked pink against her skin.

“Emily lived here for most of her life. She moved to this town when she was eight and stayed in this house until she died. Her sister lived here also. This was the room where Emily spent most of her time. Lavinia didn’t like to come in here because it smelled like her father. Emily liked to be in here for the same reason.”

Linden ran her hands over the pages of the book and began to hum lowly, lowly, lowly. The sound of her own voice calmed her. Gnarls Barkley sat down beside her. “Keep talking,” Linden encouraged when Charlotte paused. She felt the jeebies crawling under her skin. She closed her eyes and hummed louder.

“This room was special because it was full of books and Emily loved learning. It’s funny, she enjoyed biology the most. She used to study her father’s old biology textbooks. Insects have been around for 350 million years, they have the smallest brains but still found a way to survive longer than any other animals.” Charlotte looked alarmed, as if she heard what she was saying for the first time.

Linden tried to ignore the tingling in her fingers as she continued to hum. It was the same sensation that had tickled her skin when she was kneeling at Gnarls Barkley’s grave.

“I think I’ll sit at the desk.” Charlotte sat on the wooden chair and pulled a pencil out from a drawer. She had left it there from a previous night when she had sat in the same spot, trying to write a poem about a barred owl she saw sitting in the tree by the window.

“I always wanted to write about biology,” she said, her voice was much lower than usual. Linden stopped humming. Her teeth began chattering and she noticed how the temperature had dropped in the room. She grabbed the dice and shook them in her palm.

“A science—so the Savant’s say, “Comparative Anatomy”—By which a single bone,” Charlotte wrote the words along the top of a blank sheet of paper as she spoke aloud. Linden listened to the sound of the pencil scratching marks harshly onto the paper.

“Charlotte,” she whispered. “What are you doing?”

Charlotte turned and looked at Linden blankly. “I’m writing a poem,” she said. Then she turned back to the paper and finished the lines as if they were being written for the first time.

Linden watched Gnarls Barkley circle and take a step back.

He began to howl.

• • •

Emily Dickinson was fifty-five when she died. An unlucky age, Charlotte thought. She died peacefully, in her bedroom, at home. Charlotte didn’t like to think about death, but she wondered about the moments right before. Emily had Bright’s disease but no one was really sure if that was what killed her. Maybe she died from a brain hemorrhage. Maybe she died from a heart attack. Maybe it felt like nothing. Maybe it didn’t.

When Charlotte took Linden to the bedroom she inhaled deeply. The scent was always the strongest here. Everything in the room was white. White walls, white curtains, white dresser, white dress. The dress was her favorite part. It hung on a stand in a glass box where the tourists weren’t able to touch it. Charlotte found the key in a small box on the dresser.

Linden didn’t understand the difference between being dead and being gone, gone, gone. Her father wasn’t dead, but he wasn’t in Amherst.

“I don’t think you should take that out,” Linden said as Charlotte opened the glass case and began to unbutton the back of the dress.

“Emily Dickinson had one request for her funeral,” Charlotte said, ignoring Linden. “She wanted to be buried in a white coffin.”

Charlotte didn’t go to her brother’s funeral. She went to the river instead. It was colder than usual and the water was wild. She walked along the edge slowly, letting the sides of her bare feet tip toward the rushing water. She didn’t think about the way her brother’s body looked inside the coffin at the church. How his skin had aged twenty years from four hours of being submerged in water. She didn’t think about how his body was thrown against rocks, caught in tangles of weeds, and pounded against banks, the bones broken and skin scarred. She knew she could never look at him again. She could never look in his water-filled eyes without wondering if she could have saved him.

• • •

Charlotte undid the last button and pulled the dress from the stand. It felt heavy in her hands. She brought the fabric to her nose and inhaled. The smell was oddly familiar. She thought she heard the sound of rushing water and she turned sharply. The room was silent.

“Can you help me with the buttons?” Charlotte asked Linden as she pulled her own shirt over her head and stepped into the dress.

“I think we should go home,” Linden said. Charlotte ignored her and began to work the buttons herself. The sleeves were too short and crept up her forearms.

“What are you going to do?” Linden asked Charlotte when the dress was securely fastened around her body. The girl was rattling the dice in her palm.

Charlotte didn’t answer but lay down on the twin bed. “This is how Emily Dickinson would have looked.” She closed her eyes. “Right before she died.”

• • •

It was Charlotte’s idea to go to the cemetery. It was a short walk from the museum. The grave was surrounded by an iron fence and a tall oak shaded the square of grass. The cemetery was old and many of the gravestones were askew and decayed. Linden liked to trace the epigraphs with paper and colored pencils. Sometimes that was the only way to be able to see the dates and Linden liked that. But tonight she was wary of the wilted flowers and upturned angels. She followed Charlotte obediently, her feet trailing the shadow of Emily Dickinson’s white housedress. Charlotte’s skin was so pale in the moonlight it was nearly translucent.

Charlotte was convinced that it was at the poet’s grave that Emily Dickinson would come back from the dead.

“Why is this so important?” Linden asked her. “Why is it so important that we raise Emily Dickinson from the dead? This isn’t a fun game anymore.” Linden always liked games. She liked the challenge of them. She liked the rules. When Charlotte first asked her to go to the poet’s house, it sounded like a challenge. A game. Now, following the shadow of a girl dressed in a dead woman’s dress, the rules had been broken.

“Wouldn’t you like to know what death is like?” Charlotte asked. Her voice was so quiet Linden could barely hear her words. “Maybe there is a river there.”

Linden flapped her hands by her ears. “Three hundred and fifty people die each year from drowning,” she said.

Charlotte stopped.

“I know this is true because I read it in the New York Times when I lived in a brown house 942 miles away before my mom and I packed 25 boxes into an orange truck and my dad was gone, gone, gone.”

Charlotte paused and Linden wondered if she was going to turn around. She wanted to tell Charlotte that she didn’t know if she could raise Emily Dickinson from the dead, that she knew about her brother and this wouldn’t take back what happened at the river, and that her father might not live in a blue house 2,000 miles away because she had never actually seen these things.

Charlotte started walking. “Because I could not stop for death—he kindly stopped for me,” recited Charlotte.

Linden rattled the dice.

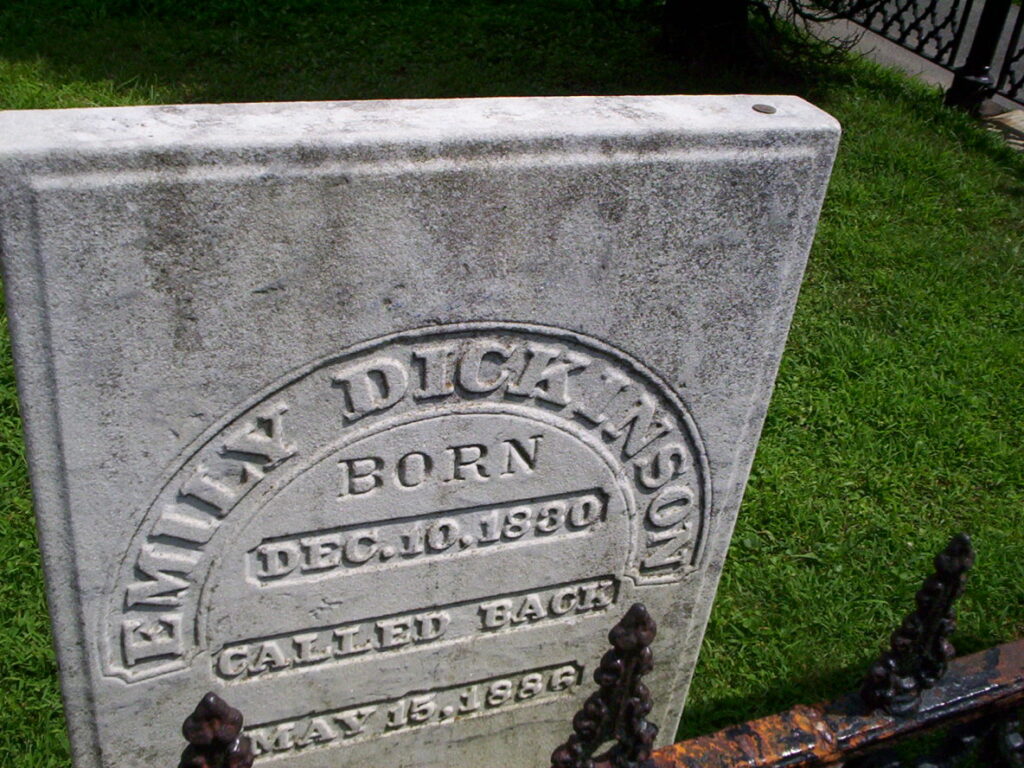

Charlotte unlatched the gate to the Dickinson plot and let her hands touch Emily’s gravestone. It was tall and nearly reached Linden’s shoulders. There were small offerings—flowers, poems, rocks, and pieces of paper—surrounding the grave.

Charlotte fell to her knees and Linden knew that the dress would stain. Charlotte wouldn’t be working at the museum anymore, she thought. Gnarls Barkley was circling the fence, a low growl rumbling from his mouth.

Linden squeezed the dice in her palm so tightly she was sure they would leave red marks. She watched Charlotte lie on her back, on the ground, her body directly over the bones of Emily Dickinson. Charlotte folded her arms over her chest and closed her eyes. Linden imagined the soul of Dickinson rising up and seeping into her. She trembled and the jeebies flooded her body. Gnarls Barkley walked up to Charlotte and sniffed her body before lying down beside her. For a moment, Linden wondered which one was the ghost. The night was alive with darkness and Linden closed her eyes. When she opened them Charlotte was still there, lying on the ground and waiting for her breath to even. Linden closed her eyes again and everything was still.