Echo’s Bones

Samuel Beckett

Grove Press, $22 (cloth)

In 1932 Samuel Beckett finished his first novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, which went on to be rejected by every publisher he sent it to and would remain unpublished until 1992, three years after his death. Discouraged, he decided to try his hand at another kind of fiction, a collection of short stories for which he plagiarized his own work from Dream and its various preparatory notes. In 1933 he submitted the collection to the London publishing house of Chatto and Windus (“Shatton and Windup,” he called them). Charles Prentice, his editor, agreed after much prevarication to publish the collection, by then titled More Pricks than Kicks. But he reckoned the book needed another 10,000 words to pad it out to a suitable, that is, saleable, length. Accordingly Prentice requested an additional story or stories from the author.

Beckett, then twenty-six years old, was at one of many low points in his young life. He was back in Dublin after gallivanting across Europe on the family dime. He was unemployed, having quit his lecturing job at Trinity College, Dublin, and nearly broke. His beloved father William and cousin and erstwhile lover Peggy Sinclair had just died within months of each other, and he was suffering from the psychosomatic ailments that constantly plagued him: boils, insomnia, cardiac arrhythmia, night sweats, and panic attacks. He craved escape, resolution, closure—and glory.

Joyce had made the modernist idiom, the literary idiom, the Irish idiom. Beckett, struggling to find his voice, was more susceptible than most.

Desperate for publication and the better life he hoped it would bring, Beckett willingly agreed to Prentice’s request. He decided to work up another story featuring the protagonist of More Pricks, Belacqua, named for the lazy lute-maker in Dante's Purgatorio. Never mind that he’d killed him off in the penultimate story of the collection. No problem, he thought; we’ll just abolish death for the duration.

The result is Echo’s Bones, whose plot, or “plot,” is simple yet convoluted. Belacqua comes back to life, or awakens to realize that he was never exactly dead, perched on a fence smoking Romeo y Julieta cigars. He converses, in the desultory, mock-learned fashion of Irish folklore, with bizarre creatures such as the huge living-yet-impotent Lord Gall of Wormwood, who incites the dead-yet-fecund Belacqua to impregnate his wife. Belacqua also holds a rambling conversation with a flirtatious prostitute named Zabarovna Privet, to whom he remarks, in typical gnomic style, “Alas, Gnaeni, the pranic bleb, is far from being a mandrake. His leprechaun lets him out about this time every Sunday.” With appropriate finality, he meets Doyle, the groundskeeper and gravedigger who appeared anonymously in “Draff,” the final story in Pricks.

In reviving Belacqua and placing him in the demented netherworld of Echo’s Bones, Beckett produced a neo-Joycean pastiche that is very likely the silliest and most turgid piece he ever wrote. Prentice turned it down flat. “It is a nightmare,” he said.

It gives me the jim-jams. . . . There are chunks I don't connect with. . . . ‘Echo’s Bones’ would, I am sure, lose the book a great many readers. People will shudder and be puzzled and confused; and they won't be keen on analysing the shudder. I am certain that ‘Echo's Bones’ would depress the sales considerably.

And so the story was consigned to oblivion for eighty-one years, until Grove Press, Beckett’s New York publisher (and mine, for The Great Pint-Pulling Olympiad, 2003), issued the novella in a standalone volume curated by the assiduous Mark Nixon. I read it with some effort, and regretfully I must take Prentice’s side, even against one of my favorite authors. After all, Beckett was still very young, uncertain of his mission, searching for his voice. The voice that comes through in Echo’s Bones is more Joyce than Beckett, but without Joyce’s wit. Its quips and caprices are arbitrary, a grab bag of stylistic tricks without conviction:

To the hair on your chest, forgive my brusqueness, my first name is Haemo don’t you see. Haemo, so beastly plethoric, all this beef you see, these steaks and collops you may have noticed, my blasted blood boils and it’s all up, I pledge you my word as apparently the last of the line I grovel before you, believe me or not sometimes I look on myself as utterly odious, I imprecate the hour I was got.

If this sounds familiar, that is because it is so heavily influenced by Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness prose, as pretty much any excerpt from Ulysses will illustrate:

I suppose they’re just getting up in China now combing out their pigtails for the day well soon have the nuns ringing the angelus they’ve nobody coming in to spoil their sleep except an odd priest or two for his night office or the alarmlock next door at cockshout clattering the brain out of itself let me see if I can doze off 1 2 3 4 5 what kind of flowers are those they invented like the stars the wallpaper in Lombard street was much nicer the apron he gave me was like that something only I only wore it twice better lower this lamp and try again.

Joyce had made the modernist idiom, the literary idiom, the Irish idiom. And Beckett was as susceptible as anyone—indeed, more than most, as an associate of the great man.

But what he ended up with was a second-rate version of his master's voice instead of his own. The music is there, but it is played off-key. No wonder he gradually switched to writing in French; it wasn’t only because French had so much less “style” than English, as Beckett claimed, but quite simply because when writing in English it was too hard to avoid Joyce’s influence. Also, at around the same time Beckett started his career as a French writer, he came to the momentous realization that he was a taker-out, a minimalist, stripping words to their essence. By contrast, his idols Dante, Proust, and Joyce were all-inclusive putters-in, crowding their texts without limit. In an important sense, his artistic idols were his opposites.

Not that Beckett was aesthetically inept, despite his young age. His abilities and potential had been on display in his 1931 monograph on Proust. There are signs of the virtuoso to come in much of More Pricks Than Kicks, especially the story “Dante and the Lobster,” a small, grim masterpiece whose conclusion—as Belacqua contemplates the death of a lobster by boiling—has become deservedly famous for its economy and wit:

Well, thought Belacqua, it’s a quick death, God help us all.

It is not.

But what is gained in style and eloquence in More Pricks Than Kicks is lost in Echo’s Bones under the dead weight of a jumble of perverse arcana and labored jokes. So obscure are most of the references that Nixon, a meticulous editor, has appended to the forty-one pages of the published text fifty-six pages of notes that attempt to untangle Beckett’s mess of learning, including scraps of St. Augustine, Thomas a Kempis, Sergei Eisenstein, Hamlet, the Bible, and the disjecta membra of countless other Beckett favorites, including Proust, Dante, and (surprise!) Joyce.

Beckett never bothered much with plot or location; he is all character, atmosphere, and, of course, dialogue. The combination works masterfully in Watt, or the Trilogy, not to mention Godot. But those works lay far in the future when Beckett was writing Echo’s Bones. The dialogue meanders pointlessly; the location shifts here and there before finally coming home to the graveyard. For in the end, of course, it is The End, and Belacqua resumes his death, spurred on his way by the shock of having to relive life.

This is a standard enough theme in Beckett: the horrors of life. But the horrors are more diffuse in Echo’s Bones. Throughout the story, the perplexed Belacqua struggles to understand his (un)dead condition, or, in Beckett’s words, to “conceive of his exuviae as preserved in an urn or other receptacle in some kind person’s sanctum or as drifting about like a cloud of randy pollen.” But “somehow” he cannot “quite bring it off, this simple little flight.”

True enough. And, likewise, the author could not quite bring it off, this simple little flight of fancy. But he had failed before and, in time, learned enough from his failure to fail better when he failed again.

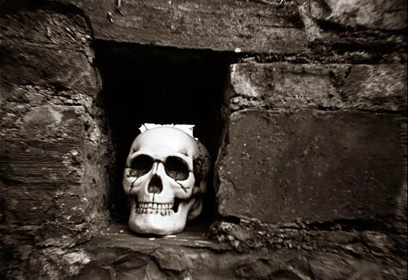

Photograph: Eddie