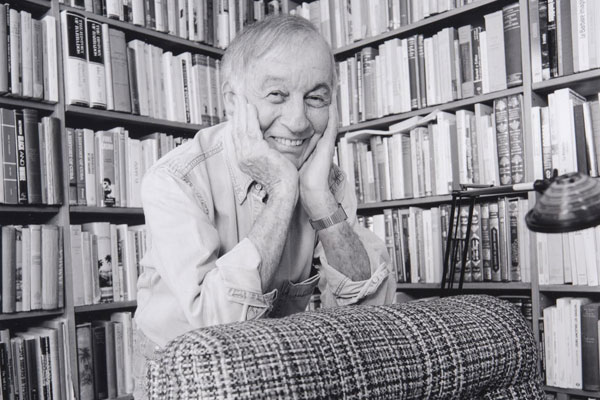

Photo credit: Johns Hopkins University, Homewood

Editors' note: This article was originally posted in late December 2015, shortly after Sidney Mintz's death. The text was then revised for our March/April 2016 print issue. The text shared here is the revised version. Reader comments from prior to March 8 pertain to the original online version.

Before there was Salt, there was sugar. Before there were Coal, Ice, and Banana, there was sugar. Before there was a long list of one-word-titled, bestselling histories about globe-shaping commodities, there was Sidney Mintz’s ur text of the ur commodity of the modern world, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (1985). With it, Mintz’s accomplishments went far beyond launching a new mode of history writing; the book also contributed to a sea change that placed the human production of inequality at the center of anthropology and offered a profound correction to how we understand modern history.

Published in 1985, Sweetness and Power accounted for New and Old World histories, the rise of Atlantic slavery and industrialism, and more than five hundred years of elite and plebeian tastes, folding them into one easily digestible confection. Sweetness and Power explained how we live—how world market systems shape taste and vice versa—in ways that no previous book had managed. It became a powerful model for how to write history, not through great men or great events, but through fungible, ubiquitous commodities and the freightedness of taste. Without Mintz’s slim volume, it is hard to imagine the careers of many other writers who have copied his mystical formula for revealing the weight of the past on the present: all the world in a grain of sand, sugar, salt. One of the tricks of history is that extraordinary things can, in time, become commonplace. Mintz showed us how to see them as extraordinary again.

Mintz’s history of sugar also joined two academic disciplines—anthropology and history—that have long struggled for compatibility. In Sweetness and Power, he explained:

Though I do not accept uncritically the dictum that anthropology must become history or be nothing at all, I believe that without history its explanatory power is seriously compromised. Social phenomena are by their nature historical, which is to say that the relationship among events in one ‘moment’ can never be abstracted from their past and future setting.

Trained as an anthropologist by Franz Boas’s student Ruth Benedict, Mintz invested in the concerns of the historically minded Boas more than those of the culturally particularist Benedict. An early reader of Marx, Mintz’s approach to anthropology contained echoes of Marx’s famous statement about history: men make their own but do not choose how they do so. Mintz turned that phrase into a formula for understanding that people create their own cultures, as Marx said of history, “under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

Along with his best friend and fellow Columbia University graduate Eric Wolf, Mintz attended not just to the past, but to the contingent past, exploding anthropology’s practice of synchronic description, the so-called “ethnographic present.” In this mode, anthropologists wrote as if their “primitive” subjects never changed, rendering those trapped in “culture” (folk traditions or exotic foreign customs) as people possessed of neither a history nor a future, even those who lived under colonial regimes. Mintz and Wolf put the lie to the timelessness of such renderings. In Mintz’s and Wolf’s carefully researched histories, culture became both a historical product and a producer of future history.

Mintz brought the past to life and showed how ordinary people can drive historical change.

By placing quintessentially ahistorical subjects (slaves and indigenous peoples, for example) into historical context, Mintz not only brought the past to life. He “made us imagine what it was like to be there,” in the words of his colleague Jane Guyer, by paying “close attention to the lives of people working.” In so doing he showed how the skilled work of ordinariness—ironing, cutting cane, holding complicated bookkeeping in one’s head—drives historical change. It is difficult to overstate the impact of Mintz’s contribution here. All of the best historical scholarship today shares with Mintz a cloudy border between history and anthropology. Any recent book of history that is compelling because it takes seriously the feelings and textures of the daily lives of forgotten people owes a debt to Sid Mintz, who pushed historians to write with anthropological instincts. More so even than anthropologists, such writers are enduring heirs to Mintz’s transformation of history into layers of unpredictable cultural successions.

At the heart of Sweetness and Power lies an understanding that the capitalism of the Atlantic world had its foundation in slavery. Drawing on the work of black Caribbean writers such as Eric Williams and C. L. R. James, Mintz helped a generation of scholars to understand that capitalism did not arise within Europe’s borders. Rather, it began in the New World, in the slaving colonies where the capital that fueled Europe’s economic shift was created. Here is how he described it in a 2013 email to Deb Chasman, one of the editors of this magazine:

My point—it is now absorbed into what is called ‘common knowledge’—was that Western civilization really first ‘rose’ in its colonies; and of all those colonies, the first were the sugar colonies.

Baltimore radio host Marc Steiner says that Mintz considered the present a product of the “Africanized world,” given the foundational importance of slavery to not just U.S. history but also to modernity itself. Recent lauded books—Greg Grandin’s The Empire of Necessity (2014), Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton (2014), Ned and Constance Sublette’s The American Slave Coast (2015), Daniel Rassmussen’s American Uprising (2011)—elaborate on Mintz’s understanding that we still live today with the blood of enslaved Africans on our hands.

But Mintz would be the first to demur over being seen as the founder of this lineage. He always attributed that credit to another Boas student, Melville Herskovits, whose 1941 Myth of the Negro Past sought a history for New World blacks that was traceable to the African societies from which they had been ripped. But where Herskovits saw in black Americans passive vessels of the past, Mintz saw creative producers of new cultural forms, despite Atlantic slavery’s brutal destruction of African cultures. Mintz’s gift for using devastatingly clear language to draw connections between slavery and the present day also shone brightly in the pages of this magazine, particularly in his takedown of the mainstream media’s shoulder shrugging in the wake of the 2010 Haitian earthquake.

For all his importance as a scholar and shaper of how we do and read history today, Mintz was also a teacher like no other. Drexel Woodson, a black student from Philadelphia studying at Yale in 1969, told Mintz that his claim that slavery was “the greatest institution in the history of the West” was “bullshit.” When challenged, Mintz elaborated (over beers, it turned out) agreeing that this was a deeply offensive fact. And yet, he told Woodson, slavery was monumental, because it endured for three centuries, involved human beings from four continents, was intimately linked to the rise of modern, global capitalism, and had a profound impact on the lives and livelihoods of millions of people—enslaved, emancipated, and free—on both sides of the Atlantic to this day. Mintz wondered aloud how different our present would be if the emancipators had bothered to ask the “freed” what kind of society they wanted—and then heeded their wishes. Perhaps the descendants of chattel slavery would then have been endowed with far more opportunities than what they wound up with: wage slavery.

In my initial meeting with him, I learned that he eschewed faculty honorifics in favor of his more genial first name. All of his graduate students called him, simply, Sid. This makes perfect sense for a man who studied the world from the bottom up, who made history’s victims into its protagonists. Mintz modeled for us what he wanted our scholarship to be: an excavation of stories that no one else would bother to tell and a willingness to see how important those stories really are, not only for their subjects but also for our understanding of the ways in which we all take power for granted.

But the friendliness of first names did not mean that Mintz would give any graduate student or colleague a pass. He schooled us all in his exacting standards. His attention to both big ideas and seemingly inconsequential details was humbling and often humiliating. It was never fun to experience his charm and wit morph into a surgical dismissal of a lame idea or a poorly executed good one. But from a bystander’s vantage, Mintz’s gentlemanly and ultimately withering critique of stupid scholarship made for great sport. I’ll never forget his unexpected skewering of Yale’s famous Human Relations Area Files project. He began with a bland summary that could easily be confused for praise, lulling his listeners—including a guest speaker whose work Mintz was obliquely commenting on. Then, in an abrupt verbal pirouette, he artfully dismissed the whole expensive endeavor: the project just filed all the attributes of culture into, as he called them, “little cubby-holes.” One understood that he thought such an unexamined taxonomy lacked the bigger picture of connections and meaning and certainly failed to understand historical forces acting upon those behavioral artifacts.

We all knew Mintz to be a great lecturer; the stories of his overflowing classrooms at Yale were legion. But what I took from him as a teacher were more subtle lessons in compassion, humanity, and accomplishment. He once changed the grade of a struggling student for reasons that I could not fathom. Only after I had taught for some time did I understand that he must not have thought grades a very meaningful marker of a human being. To Mintz grades told the story of how higher education reflects the larger context of privilege and social sorting of which it is both a part and producer. But he also recognized that a grade did matter to a scared, lost undergraduate. He cared for things far less obvious but much more important: conduct your research with rigor, get your facts straight, don’t over-conclude, and catch your typos before you go to print. He once wrote to me that my best work is sometimes marred by lamentable errors that a reader will never forget or forgive, a lesson that haunts me even as I write this and one that I have passed on to haunt my own students.

Almost anyone who spent time with Mintz will delight in a memory of a meal with him—a perhaps unsurprising extension of his deep investment in the social significance of food and drink. A friend from my generation of graduate students described dinner with Mintz at a Chinese restaurant as “like eating in a library.” In her recent remembrance, food scholar Marion Nestle credits Mintz as a foundational figure in food studies and notes that in a recent poll, Sweetness and Power was the only book all food studies scholars could agree was an indispensable part of their discipline’s canon. Showing the breadth and depth of his impact beyond anthropology, historians and public intellectuals have poured out on social media their tributes and memories, testifying to a man who hosted many and nourished a community of scholars and writers who will always hunger for more.

One of Sweetness and Power’s great contributions is its luscious details showing how sugar became a food—indeed the food—that fueled the Industrial Revolution, providing the cheap calories that fed both enslaved and free laborers throughout the Atlantic world. From sugar, it was a short step to the other foods comprising the cuisines, their limits and broad horizons, of the societies that Mintz explored. I first encountered him in a student’s kitchen. There I watched a culinary wizard make a Mexican mole from scratch, all the while telling me about the culture and history of the laborers who had cultivated the dozens of plants essential to the dish. In my mind, Mintz’s two adult children captured two of his most appealing and wonderful traits: his love of food and his fight for any underdog. His daughter is a social worker and his son, a diarrheal epidemiologist, has studied food-borne illness outbreaks, among other important contributions.

Sid Mintz died in December of last year, well before any of us imagined he would, at the age of ninety-three, after a head injury caused by a fall. He leaves behind not only his family and the legacy I have touched on here, but also a pair of indulged cats. What he loved in his cats is what I suspect we all loved in him: you might admire their hunting skills, but mostly you enjoy their giddy, unself-conscious affection.

Mintz fed a broad world both inside and out of the academy with his generosity and kindness. A cabinetmaker I met while a graduate student in Baltimore praised Mintz and his wife Jackie as among his favorite clients. This indirect encounter with Mintz told me something about how to live in the world beyond the ivory tower: with deep and vocal respect for the labor of others. Every scholar wants to be remembered for his or her great works, but every human should aspire, as Mintz did, to be remembered for simple human decency.