Specimen Days

Michael Cunningham

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $25 (cloth)

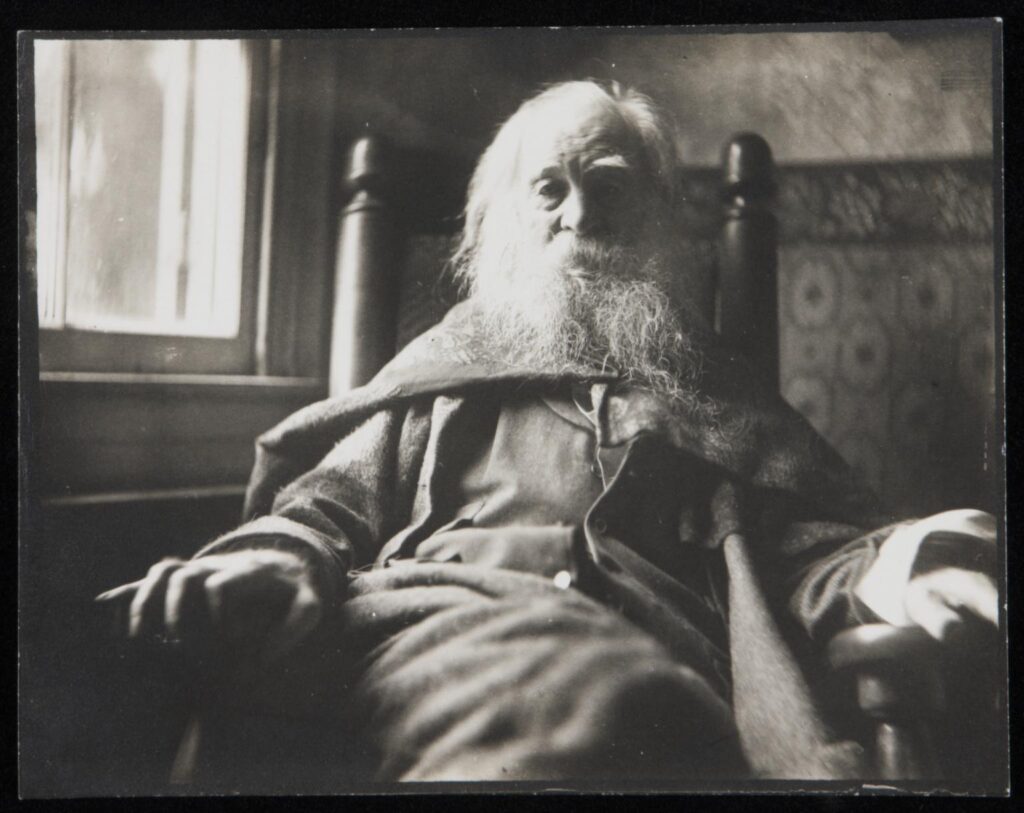

When I heard that Michael Cunningham had written a book in which Walt Whitman presides over scenes set in New York City in three different eras—Whitman’s own day, the approximate present, and a late 21st century whose human population shares the sidewalks with intelligent life from another planet—I got excited at the prospect of watching him hold our poet-father’s feet to the fire. Moved as I am when reading “Song of Myself” or “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” by Whitman’s direct address to posterity, at the same time I want to upbraid him, not so much for his outrageous optimism as for his blockheaded assumption that generations to come will be able to share it. Thus, I looked to Cunningham’s novel to portray Whitman’s reactions at seeing the adolescent democracy on which he had pinned his extravagant hopes evolve into the senile hegemon whose “boots on the ground” bestride our new millennium.

By bringing Whitman’s legend and his texts into a book titled Specimen Days (after a volume of incidental prose compiled by the poet near the end of his life), Cunningham seems at first glance to be attempting to replicate the blend of canonical tribute, biomythography, and clever social observation that made his Pulitzer Prize–winning The Hours an echo chamber of eerie satisfactions. And Specimen Days does offer a new edition of the trompe l’oeil effects of The Hours, achieved through an artful arrangement of arbitrary-seeming actions and images that repeat throughout several narrative threads. The writing ranges from deft to gorgeous, displaying Cunningham’s talent for coming up with compelling lyrical images and splendidly unexpected details.

But Specimen Days is not The Hours II. In contrast to the somber, fugue-like unity of the earlier book, this one is more like an experimental purée of tofu, capers, and raspberry sauce. And it is far more ambitious in scope, nearly breaking out of the imperial cocoon that makes “the way we live now”—i.e., how middle-class individuals conduct their private lives—the compulsory focus of mainstream American fiction.

I read Cunningham’s panoramic timescape, and in particular his projection of a coming era shaped by a devastating technological glitch (“the meltdown”), as a response to existential anxieties that have been seeping into the cultural groundwater since at least the bombing of Hiroshima and are now resurgent, though often obscured. It is one of the chief mysteries of our cultural life that the disasters of the past few years have not pushed more literature to revisit that blunt Cold War question: suppose we’re on the verge of the ultimate mistake, the one that will do our species in?

That Cunningham addresses this issue while repudiating the paranoia that typically projects our own destructive potential onto some Evil Other is a virtue not to be sneezed at. For example, he slyly imagines a post-9/11 New York stalked by terror in the form of suicide attacks carried out by discarded American children.

Yet the book is dissatisfying. The problems start with Whitman, who, unlike Virginia Woolf in The Hours, gets only a walk-on part. As if to compensate, his words are everywhere, slathered over the surface of Cunningham’s narrative in sound bites recited by holy fools and lyrical androids. Cunningham seems to want us to think of Whitman’s poetry as a sort of American common text, a wellspring of shared meaning as the Bible once was for Anglo-American settlers. Instead, the snippets take on a fetishistic ring—a jarring dislocation of the poet of long lines, who typically built up his effects through layered connections and intricate parallels. This is not Whitman channeled, but Whitman channel-surfed.

There is more to be said about which Whitman or Whitmans Cunningham has chosen—one drawback of being a multitude-container is the ease with which your readerscan cherry-pick—but first it makes sense to look at the novel’s overall design. Each of its three sections tells the story of a (mostly platonic) threesome, made up of characters named Lucas, Simon, and Catherine/Cat/Catareen. Each Lucas is a deformed, precocious boy; each Simon is a hunk; the variant Catherines are courageous, maternal beauties. The theme of their interactions is always sacrifice, and each story climaxes with a scene that the trailer for the superfluous movie version will surely label a “triumph of the human spirit.” Each story is told from a single character’s point of view.

In the opening section, “In the Machine,” that character is “pumpkin-headed” Lucas, an impoverished Irish immigrant whose stigmata are accompanied by a verbatim recall of much of Whitman’s masterwork. This section is essentially static, a dream world of terrible, beautiful images: Lucas tending the metal-stamping machine that killed his older brother; burning women perched on high window ledges before leaping to their deaths near Union Square. Though “In the Machine” takes place in the 19th century, the episode of the burning women evokes the notorious Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire of 1911, while looking forward to our own 9/11—a reframing as ingenious and suggestive as the later image of homegrown suicide bombers.

Cunningham’s immigrants are still haunted by Old World trauma, sleepwalking through the daily nightmare of classic wage slavery. Here is Lucas, worn out by his brutal industrial job, trying to tend his ill and addled father:

He cooked the egg and boiled the cabbage, and set a plate before his father. He was seized by an urge to take his father’s head in his hands and knock it sharply against the table’s edge, as Dan did with his machine at the works, knocking it when it threatened to seize up, ringing his wrench against its side. Lucas imagined that if he tapped his father’s head against the wood with precisely the correct force he might jar him back to himself. It would be not violence but kindness. It would be a cure. He laid one hand on his father’s smooth head but only caressed it.

Here Cunningham’s compassionate vision merges physical experience and fantasy to give specific weight and shape to a character’s inner life, laying bare the emotional logic behind thoughts and actions that might otherwise seem bizarre.

However, my suspended disbelief abruptly resumes when Lucas develops an idée fixe (the dead, including his brother, live on inside machines) whose obvious symbolism makes Lucas seem like the author’s pawn. The boy destroys himself—literally feeds his body to the machine—to save Catherine, who was his brother’s sweetheart and is now pregnant with the dead man’s child.

Lucas’s death seems overdetermined, the product of vicious historical conditions (the Irish famine, exploitative industry); of mental unbalance (which runs in his family); and of the novel’s need for an apotheosis of Whitman’s vision. It is hard to decide how we are meant to connect these levels of meaning, and eclectic formal choices in the novel’s middle and closing sections only intensify the puzzle.

In part two, “The Children’s Crusade,” we leave the slow-moving dream for a plot-and-dialogue-driven detective novel. Less a character than a genre convention, Cat is a plucky detective haunted by personal tragedy. Like Irish Lucas, she is “other”: not only a female cop, but black. Her decision to attempt the rescue of one of the child bombers gives readers the never-to-be-exhausted pleasure of identifying with the deserving underdog’s personal solution:

He [the rescued child] had ended her life and taken her into this new one, this crazy rebirth, hurtling forward on a train into the vast confusion of the world, its simultaneous and never-ending collapse and regeneration, its rock-hard little promises, its owners and workers, its sanctuaries that never endured, that were never meant to endure.

To die is different from what any one supposes, and luckier.

The child kept smiling his murderous smile.

Cat smiled back.

Part three, “Like Beauty,” transports us to yet another genre universe, a curiously retro-tinged science-fiction future with overtones of Margaret Atwood (a brush with a loutish bunch of fundamentalists recalls The Handmaid’s Tale), William Gibson (dystopia bears traces of utopias gone by) and Samuel Delany (multiculturalism figured as intimacy between lizard-like aliens and humans echoes Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand). There’s even a touch of Frankenstein in “simulo” Simon’s search for the father figure who fused his cell lines with his circuitry. As in “The Children’s Crusade,” the plot machine hums along; the conceit that Simon’s maker has programmed him to be in Denver on a specific date is no sillier than many a pretext for a literary road trip.

Cunningham playfully comments on the pileup of hoary tropes through his choice of vehicle for Simon and his companion, the alien Catareen. Together with a sidekick named Lucas, they travel in “an ancient Winnebago covered in faded decals that depicted guns, fish, and mammals.” “Like Beauty” pointedly rejects the usual ambition of speculative fiction: to offer an original glimpse of a possible future. But what, then, is the point?

Whatever the intent, the effect is emphatic reassurance that the future will not be new. It holds no terrors we have not already been exposed to and will require no innovative formal strategies. The mechanical maw that swallowed 19th-century Lucas is simply domesticated in the person of Simon, who at one point, in one of Cunningham’s better satirical forays, has a job impersonating really rough trade so tourists can enjoy the nostalgic thrill of getting mugged in Central Park. Simon’s vigil at the bedside of the dying Catareen, which is movingly written, proves that machines have feelings too.

Whereas the classics of speculative fiction evoked in “Like Beauty” portray the human future as a dicey proposition, Simon-the-simulo’s story invites us to believe that there will always be a safety net. Intelligent, feeling life will endure and prevail, even as people morph into cyborgs or engender half-lizard offspring.

* * *

A derivative of the notion that blood is thicker than water animates Cunningham’s fiction. This at first seems surprising given his fondness for portraying refugees from standard patriarchal arrangements. On close inspection, however, his post-1960s domestic coalitions of disaffected straight women, homosexuals, and other “others” (artists, the mentally ill, the racially stigmatized) emerge as advertisements for rock-solid alternative family values.

Gay readers have sometimes reproached Cunningham for letting down the side by not writing more specifically for a gay audience. Although I do not think any writer’s imagination ought to be limited by identity politics, I confess to nursing a related disappointment: I keep wanting Cunningham’s work to be queer, and it’s just not. His characters, for all their discontent, do not desire revolution. Although three of his novels register the traumatic effects of HIV/AIDS, none of the protagonists reaches the outraged conclusion of David Wojnarowicz in his blistering AIDS memoir Close to the Knives: “When I was told that I’d contracted this virus it didn’t take me long to realize that I’d contracted a diseased society as well.” Cunningham’s misfits—sexual and otherwise—seem to ask plaintively, “Can’t we all just get along?” And when the answer comes back no, they light out for the territory, a polluted yet idealized realm that appears in many guises: “five miles out of Woodstock,” Death, Florida, Art, California, or another solar system.

This motif of escape obscures but cannot totally eclipse the novels’ apprehension of a dark kernel of grief at the center of things, an apprehension distilled in some of Cunningham’s most successful lyrical writing: the half-chosen drowning death of Ben in Flesh and Blood, Lucas’s dream world of industrial servitude in Specimen Days, and the eerily tender portrayal of Virginia Woolf’s suicide in the opening section of The Hours:

She comes to rest, eventually, against one of the pilings of the bridge at Southease. The current presses her, worries her, but she is firmly positioned at the base of the squat, square column, with her back to the river and her face against the stone. . . . Some distance above her is the bright, rippled surface. The sky reflects unsteadily there, white and heavy with clouds, traversed by the black cutout shapes of rooks. . . . Her face, pressed sideways to the piling, absorbs it all.

It is the subtle way in which this passage deploys point of view that, together with its physical clarity, creates its emotional impact. The image is one of effacement, yet Virginia Woolf’s face—the emblem of personality, of individual consciousness—is still receptive, still an “interface” with the world. The quintessential subject, the artist-observer, has become the observed without being objectified. Life and death communicate through a semi-permeable membrane.

Point of view is perhaps behind my unease with how Cunningham handles his darker promptings elsewhere. From A Home at the End of the World to Specimen Days, the novels are narrated from multiple points of view, but are almost always tightly bound to a single center of consciousness within a given chapter or section. This technique functions as a modern substitute for old-fashioned omniscience: the meaning is in the whole, and God is whoever grasps it. But unlike the older technique, which imposes a burden of responsible commentary on the omniscient narrator, Cunningham’s approach shuns explicit conclusions. It creates an illusion of a level playing field, with characters’ thoughts and actions left to speak for themselves.

Without a central voice helping us to decide what weight should be assigned to these different perspectives, Cunningham leaves us with many questions. Even powerful passages depicting death and dying hang suspended like lumps in cake batter; these events cannot be processed by the surviving characters—neither dismissed nor articulated. While there is a sense in which we do experience deaths as indigestible lumps, successful writing helps us out, gives us a formal mechanism for addressing, however provisionally, the emotional stalemate. By habitually shifting the point of view to relatively buoyant survivors, Cunningham makes it difficult to decide how much attention we should pay to those darker intimations. Death, from this narrative stance, is always someone else’s death.

The Hours is an exception to this rule, as the passage about Virginia Woolf’s body illustrates; the centrality of Virginia Woolf’s fictionalized character helps supply clarity, as does the way in which her mortality-steeped fiction haunts Cunningham’s text. In Specimen Days, however, the many images of death—Lucas’s sacrifice; the burning, leaping garment workers; the ravaged and polluted continent; Catareen’s lonely end—are viewed from a distant place in which no loss need be grieved too bitterly, for there will always be a next time.

The materials are tragic. The treatment is not.

* * * I have said somewhere that the three Presidentiads preceding 1861 show’d how the weakness and wickedness of rulers are just as eligible here in America under republican, as in Europe under dynastic influences. But what can I say of that prompt and splendid wrestling with secession slavery, the arch-enemy personified, the instant he unmistakably show’d his face? The volcanic upheaval of the nation, after that firing on the flag at Charleston . . . will remain as the grandest and most encouraging spectacle yet vouchsafed in any age, old or new, to political progress and democracy.

—Walt Whitman, Specimen Days

Crazy, Simon thought. They’re all crazy. Though of course the passengers on the Mayflower had probably been like this, too: zealots and oddballs and ne’er-do-wells, setting out to colonize a new world because the known world wasn’t much interested in their furtive and quirky passions. It had probably always been thus, not only aboard the Mayflower but on the Viking ships; on the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María . . . It was nut jobs. It was hysterics and visionaries and petty criminals.

—Michael Cunningham, Specimen Days

Specimen Days by Walt Whitman was conceived, its author boasts, as the “most wayward, spontaneous, fragmentary book ever printed.” The fragments include an autobiographical sketch outlining his family’s farming roots on Long Island, notes on his informal but arduous service as a morale-booster to the wounded and dying in army hospitals during the Civil War, and impressions of nature recorded during his own convalescence from a stroke. Whitman offers his “common individual New World private life” as a unique but representative “specimen” of American experience in the mid-19th century. He finds his political vision incarnated in the beautiful bodies and vigorous psyches of the common man, repeatedly evoking an eroticized republic of ferrymen, “stage-drivers,” and heroic Union grunts: “I found them full of gayety, endurance, and . . . the most excellent good manliness of the world. . . . I never before so realized the majesty and reality of the American people en masse.” He likewise praises the body of the continent itself (at one point thrilling to a scheme to fill the Great Plains with forests). There are times during his 1879 railroad trip out west when his rhapsodic bulletins shade into press releases for Manifest Destiny.

Despite their parallel upbeat rhetoric, the temperamental and philosophical dissimilarity between Whitman’s eccentric text and Cunningham’s pastiche can hardly be overstated. For one thing, as the passage about the Civil War quoted above illustrates, the first Specimen Days takes history seriously. Whitman’s optimism fed on the belief that American democracy signaled lasting progress for humanity as a whole—not because he ever dreamed America would spread “freedom” at gunpoint, but because he thought government for and by the people would confront tyranny with the threat of a good example. He saw the Civil War as a just if terrible conflict, both because it ended slavery and because it vindicated the union on which he staked his hopes for society. As much as he admired independence of spirit, he knew full well that “furtive and quirky passions” need translating into democratic structures. I can’t believe he would applaud Cunningham’s instinct to answer the terrifying prospect of our shrinking liberties and expanding imperial reach by simply changing the point of view.

Although its structure enacts a message of eternal recurrence, Cunningham’s Specimen Days reflects received notions of the nation’s upward-trending destiny. The past is full of hardship, its immigrant masses toiling just to stay alive; the present is a bewildering marketplace in which individuals freed from obsolete strictures (of gender and race, for instance) navigate a blurry landscape of threats and opportunities; the future is wide open and the cheeriest time period of the three. The continent’s squandered environmental and political inheritance notwithstanding, it will always be Morning in America:

He would ride west, [Simon] thought. He would ride to California. He would ride in that direction. He and the horse might die of starvation or the sun. They might be attacked by nomads and zealots. Or they might get to the Pacific. They might go all the way to the far edge of the continent and stand on a beach before what he imagined to be a restive, infinite blue. Assuming of course that the ocean was still untainted.

Though a pristine ocean seems unlikely given what we’ve been told about the devastated heartland, Simon’s plan seems less naive than Cunningham’s omission of global warming from his vision of the late-21st-century landscape. In effect, he has roused our fear that the “procreant urge” Whitman admired in the world may prove to be no match for our destructive habits only to beguile us with a tale as affably irrelevant as Ronald Reagan’s fond belief that a nuclear missile launched in error could be recalled.

In this scheme, which I’m afraid all too accurately reflects most Americans’ insensitivity to our predicament, death still happens to other people, not to us. I’ll say it again: the materials are tragic.