This Democratic presidential primary has looked markedly different than many contests in recent memory. The ideas are bigger and bolder. Candidates are trying to tackle large, systemic problems as they also campaign to defeat President Trump. Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez have made a huge contribution to this debate by laying out the argument for a wealth tax, a mantle that was picked up by leading candidates and supported by a number of others.

Saez and Zucman are right on the economic argument they make. But, just as important, they are right on the politics, too. Yes, as they write, “extreme inequality poses a serious risk to our democracy,” and a wealth tax can reduce that danger. But more immediately, a wealth tax offers the chance for Democrats to talk about taxes as important in their own right, rather than in relation to what particular programs they might finance. This move allows them to separate the two ideas—raising taxes and spending government money—and make a case for each one separately.

This is a different kind of argument about why increasing taxes on the wealthy is important than the one we have become used to, at least in the postwar era. During their presidencies, both Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt argued for taxes on the wealthy on moral, not fiscal, grounds. In pushing for a higher income tax on high earners, for example, Teddy declared in 1910, “The really big fortune, the swollen fortune, by the mere fact of its size, acquires qualities which differentiate it in kind as well as in degree from what is possessed by men of relatively small means.”

But since at least the 1970s, Democrats have typically backed higher taxes not in these terms but specifically because they want to find new money to pay for their pet projects. That messaging has allowed them to be tarred by Republicans—even those who have no qualms about wasting money on tax cuts and wars without finding more revenue—as “tax and spend” liberals. Endorsing a wealth tax can help Democrats change this conversation about the role taxes play in our economy. Taxes can be good in and of themselves, and vital new social programs can be enacted without “paying for” every penny. A wealth tax helps disentangle the two issues from each other.

A wealth tax is not just a way to fund programs, although it is that as well.

Elizabeth Warren, who has proposed a 2 percent marginal tax rate on net worth above $50 million and 6 percent above $1 billion, would have used the money for universal childcare, Medicare for All, student debt relief, and other large investments in the wellbeing of American families. Bernie Sanders, whose wealth tax would hit net worth of $32 million or more with a 1 percent tax and then gradually increase it to 8 percent on wealth over $10 billion, would similarly put the money to work for ambitious social programs.

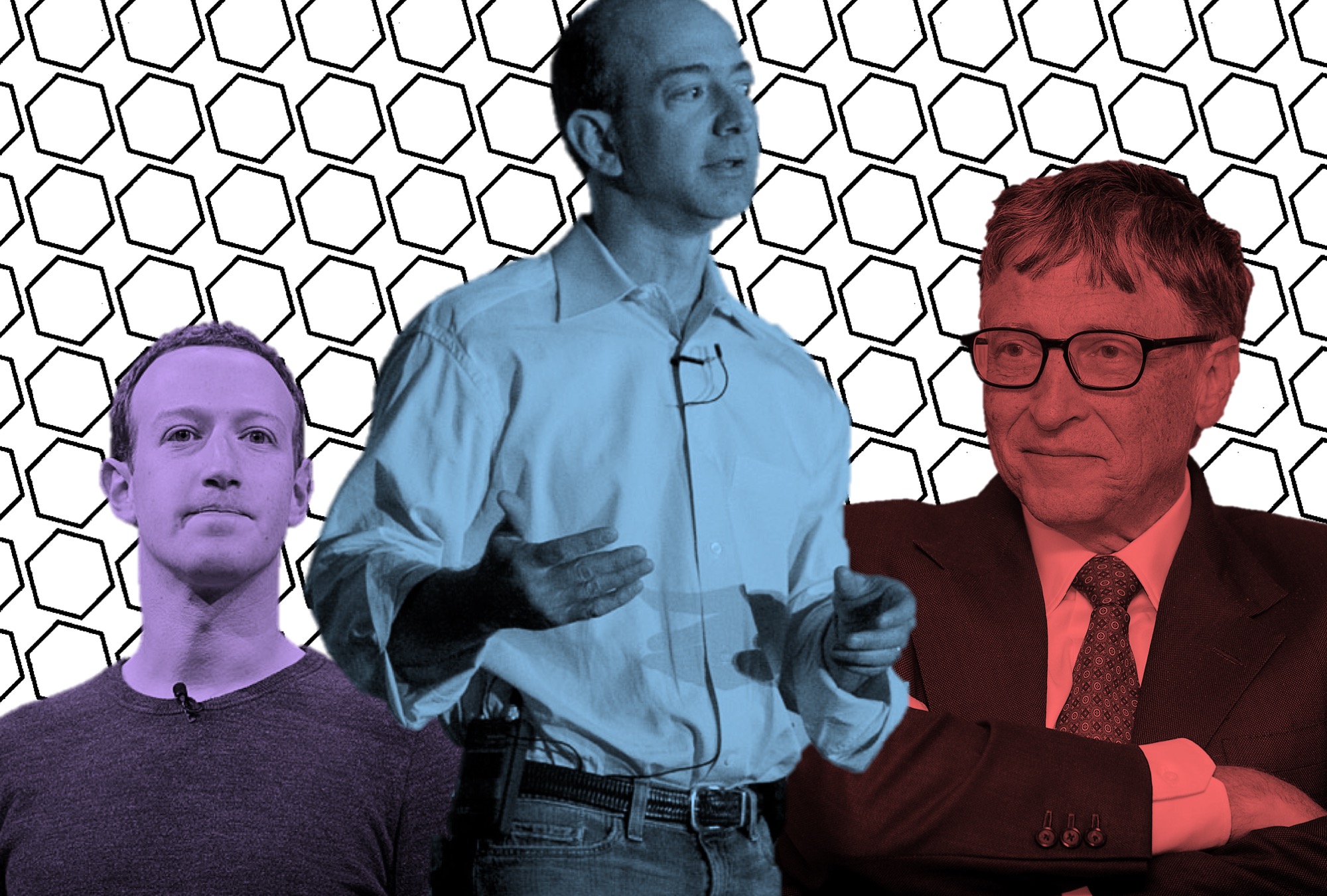

But a wealth tax is also valuable in and of itself because it reduces inequality and could reform our oligarchical system. “Wealth is power,” Zucman and Saez write. “An extreme concentration of wealth means an extreme concentration of power.” That power can then be marshaled to beget more wealth and, therefore, power. A wealth tax, then, can “help address the threat that extreme inequality poses for democracy.”

The two authors liken it to a carbon tax. Yes, such a tax would raise revenue, which could then be put to work in large-scale, vital investments. But more importantly, it is meant to discourage the thing it taxes. This is how a so-called Pigovian tax works, much like high taxes on cigarettes and alcohol. Its primary goal is not necessarily raising money, but shaping and therefore improving our society. Just like smoking or emitting carbon emissions, the accumulation of massive fortunes harms the rest of us and should be discouraged. It wouldn’t prevent people from becoming billionaires, but it would make it harder to hoard vast fortunes, which calcify money into monoliths that are only added to and never depleted.

We used to have a system that was more capable of achieving this goal. High income taxes discouraged wealth hoarding and better distributed the country’s abundance. The top marginal tax rate, reserved for only the very highest earners, was above 70 percent between 1936 and 1980, reaching as far as 94 percent toward the end of World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt didn’t institute such a tax rate just to finance the New Deal or the war effort, but to ensure that there wasn’t a ruling class of rich people that pulled away from everyone else. “Our revenue laws have operated in many ways to the unfair advantage of the few, and they have done little to prevent an unjust concentration of wealth and economic power,” he stated in 1935.

Such a tax system “achieved its objective,” Zucman and Saez write. Income inequality fell as fewer Americans were able to amass gargantuan fortunes. In 1960, they point out, just 306 families made more than $6.7 million in taxable income a year and thus faced the top 91 percent rate. Everyone benefitted from this system. Money was spread more evenly, and the economy as a whole saw strong growth.

But the top marginal income tax rate began a sharp and unrelenting decline in the ’80s, beginning with President Ronald Reagan; today it’s just 37 percent. Meanwhile, other taxes meant to ensure that the country doesn’t have an aristocracy have been defanged. The top estate tax rate, meant to curb the wealthiest’s ability to keep passing enormous fortunes down generation to generation, has fallen from 77 percent in the 1970s to just 40 percent, and thanks to a number of exemptions, just one in a thousand inheritances actually has to pay it.

I agree with Zucman and Saez that the income tax alone can’t address the many ways the ultrarich structure their fortunes to avoid taxes, and that a higher estate tax would only have the desired effect when the superrich pass on their wealth. A wealth tax, on the other hand, ensures that the very richest are adequately taxed even when they manage to squirrel away their fortunes in various avoidance vehicles and before they pass it down to their heirs. It’s insurance against the creation of an untouchable aristocratic class in a country where anyone can supposedly work hard and become financially successful.

With this tool at their disposal, Democrats can steer away from constantly feeling like they need to “pay for” their ideas with taxes. They can argue for this kind of tax as a standalone policy, freeing them up to campaign for big public programs on their own merit. It’s become such a familiar refrain on the campaign trail that few question why it gets asked so often: How would you pay for your policy proposal? That is a question that Democrats have perpetually felt compelled to answer, and one that Republicans rarely do.

Take, for example, the unfounded and completely dubious claims from the Trump administration that its massive tax cut package would pay for itself. That has not come to pass; instead, forecasts show it will add $1.9 trillion to the deficit over a decade. But no one has hounded the administration on how it will pay for the ongoing costs, nor the potential costs of the second round of tax cuts that is currently under consideration. The same has been true of countless Republican administrations. Reagan secured tax cuts and military spending that more than doubled the national debt. President George W. Bush also championed tax cuts and an increase in defense spending that doubled the debt. No one followed them around asking how they would pay for wars or tax cuts.

Democrats, on the other hand, have more or less spent the last three decades buying in to the conservative idea that taxes should be kept as low as possible, only increasing them when extra money might be needed for an important initiative. President Bill Clinton raised the top marginal income tax rate to only 39.6 percent when he was in the White House, and President Barack Obama managed to bring it back up to that exact same level (after Bush had cut it again). Obama never called for a top tax rate above 50 percent, and even his proposal for a “Buffett Rule”—which would have ensured that billionaires faced higher tax rates than their secretaries—would have done little to claw back income inequality and was instead framed as a way to “[pay] down the deficit.”

In short, the wealth tax is a good, in and of itself, not just in relation to what it pays for. Arguing for it allows Democrats to craft a different argument about their priorities. Taxes can be put to work to combat distortions in our economy and our society. Meanwhile, expansive new social programs should be enacted because they are smart investments in the country from which we will reap enormous rewards.

This framing may finally have caught on. Perhaps Democrats have learned the lesson of decades of Republicans getting away with spending what they want without paying for it. Or maybe they have realized that incremental changes in the tax code aren’t enough to match the problems we face. Either way, the new conversation about taxes is a welcome change, and just might signal the beginning of a new political era.