In discussing the potential of the left in rural spaces, we have uncovered an equally thorny topic: What, and who, do we mean when we talk about the working class? We have, rightly in my mind, assessed the left as a coalition of people and politics that aims to build working-class power, but this volume also speaks to a wider conversation about the nature of that power and how it will manifest.

Nancy Isenberg’s response shows us the danger of creating simplistic avatars of the working class, and she finds fault among both progressives and conservatives. The most damning exhibit she produces is the celebrity of J. D. Vance. But she is also right to pause and examine the ways the “star power” of left political figures such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez crowd our field of vision and absorb gendered expectations that are difficult to reconcile. “Mother Jones wouldn’t stand a chance of getting elected today,” Isenberg writes, underscoring the chauvinism that continues to animate segments of Appalachia’s working class.

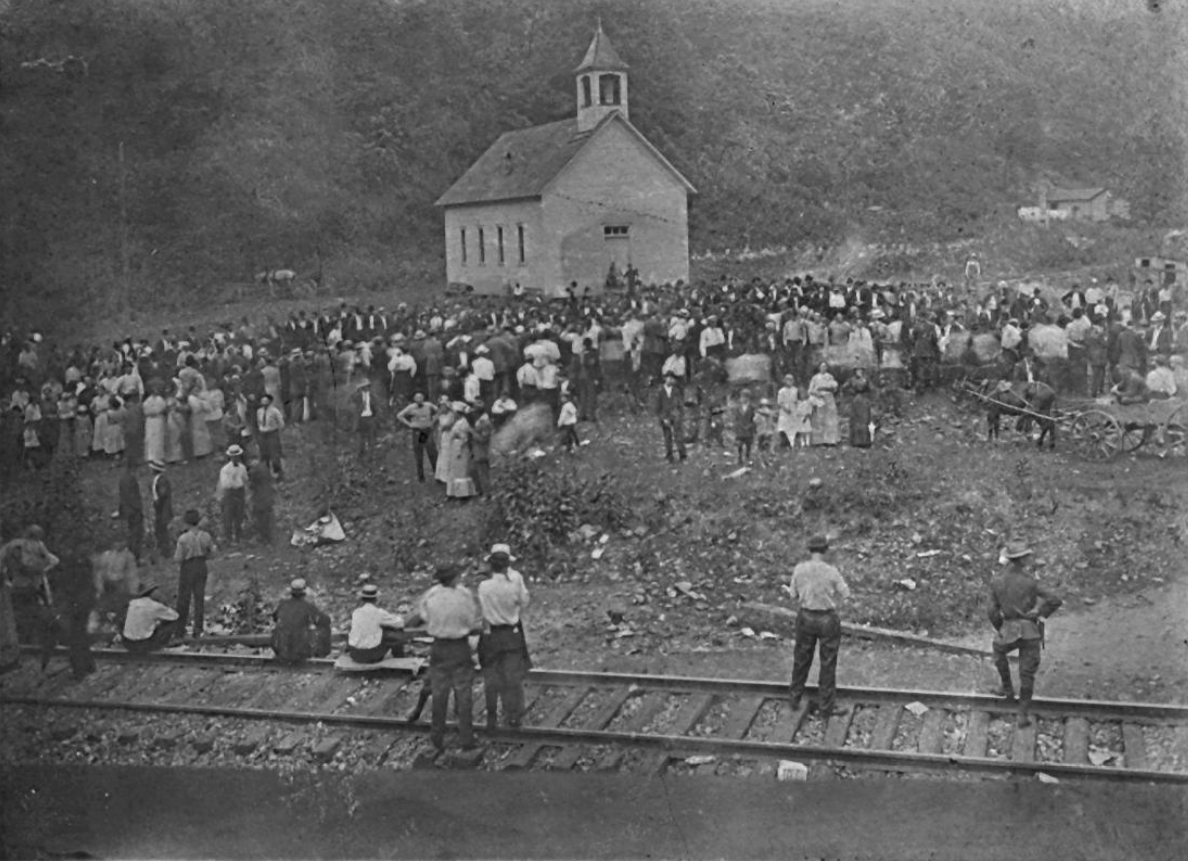

Jessica Wilkerson’s and Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson’s essays hint at the problematic way we conceptualize the working class in Appalachia. Coal miners have become the region’s most scrutinized political actors and have, for too long, obscured the contributions and realities of women and people of color.

The tendency to equate labor conflict with blue-collar, male-dominated industries such as mining is perhaps why Michael Kazin finds no evidence that “a mass of Appalachians are busy creating a new movement to emulate the labor-centered one that disappeared decades ago.” I think more than 20,000 striking teachers fit that description. Kazin is right that we find ourselves in a much different time and place from the heyday of the United Mine Workers and their vision of organized labor. But he may overstate the degree of the rupture: although coal is dying, its extractive logic persists in natural gas, a fuel that West Virginia delivered a record 1.6 trillion cubic feet of in 2017. States continue to wrap their economies around the satisfaction of tax-fearing power players. This extraction 2.0 era has led to a very different kind of labor conflict since state austerity measures disproportionately impact the public sector and those who work there, namely white women and people of color. Instead of industrial workers feeling the brunt of mismanagement, it is public sector employees—including the agitating teachers in Oklahoma and North Dakota—who struggle.

Elaine C. Kamarck’s response builds on the problems inherent in this murky transformation. In the era of “plundering bosses,” the working class had a much more direct path to power. Today this path is increasingly shaped by shifting political alliances, tax incentives, and schemes that range from focused, such as the left’s Green New Deal, to incredibly vague, such as bipartisan efforts to assimilate former blue-collar workers into the technology sector. Against whom do we organize if not bosses? Kamarck suggests politicians, but she also acknowledges that it is difficult to produce an example of “paradigm-shifting” political work among our most powerful representatives.

This dilemma is taken up most forcefully by Matt Stoller, who charts Democrats’ failures to build institutions and execute policies in the interest of the working class. I disagree with Stoller that far-left activists are confusing the woes of temporarily unfiltered markets with the problems inherent to capitalism in all its forms, but I grant him the point that discussions of dissent must weigh tangible evidence of change.

So how do we define change? The election of better representatives, as Kamarck and Stoller suggest? The creation of more equitable institutions, as Kazin demands? Or the more honest and sophisticated assessments of class in our political language that Isenberg asks for? Ruy Teixeira finds change inevitable, but assesses its arrival at a slow and uneven pace; white, rural voters might tolerate Medicare for All, but will surely grow cold at the idea of confronting U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). But Henderson reminds us that rural spaces have much to teach in that regard. In 2017 ICE conducted its largest-to-date raid on a community in Morristown, Tennessee. Residents responded with such swiftness and purpose that the New York Times labeled it “a town that fought back.” Henderson’s essay shows us how long histories of community organizing enabled that response, moving us beyond a discussion of change toward liberation. Hugh Ryan’s response also presents a rebuke to the idea that, in rural places, “change comes slowly or not at all.” Ryan’s evidence is the proliferation of queer communes in rural spaces, along with art and documentary projects that celebrate queer rural life in all its forms. These projects do not necessarily aim to effect mainstream change, such as expanded legal protections for LGBTQ individuals, but instead offer utopian visions for liberation.

Bob Moser forcefully strikes through the question of “tangible” change and bends our lens toward radical transformation, instructively citing regional political actors such as Chokwe Antar Lumumba in Jackson, Mississippi. Moser also points to the election of Justin Fairfax, who took the oath to become Virginia’s second African American lieutenant governor holding an ancestor’s freedom papers. But taking that oath meant that Fairfax would work for an administration that plans to sacrifice a community founded by freedmen (Union Hill) to an energy company (Dominion Energy) for the construction of a natural gas compressor station. To his credit, Fairfax broke rank on this issue to the extent that his position allowed, but it is this kind of dilemma—plantation politics, meet eminent domain—that moved me to stipulate that an old war continues in the present.

The peril that Moser indicates, however, is not so much acknowledging the existence of this war as bordering it with nostalgia. Nostalgia is something of a verboten emotion to critical thinkers—cloying and unhelpful—but I organize with people who live in disappearing worlds and are processing painful separations every day. Their livelihoods, yes, but also familiar landscapes that have been ruined by extraction, and, most grimly, the thousands lost to the opioid crisis. I surrender to nostalgia as an operating force in their lives and try to bend it to what Svetlana Boym might call “reflective nostalgia,” which “reveals that longing and critical thinking are not opposed to one another, as affective memories do not absolve one from compassion, judgment, or critical reflection.”

What people desire from the past often reveals what they hope for the future. Do people seek histories of dissent because they are sentimental and tragic, as Moser suggests, or because it helps them bridge the space between what was, is, and might be? The power of the poor and working class is in a moment of twilight. Is it romantic to observe that the sun rises after it sets, or is it realistic? The answer is in the eye of the beholder, but it seems we are all in agreement that we must be prepared to work in the dark.