Historical memory is both a powerful and perilous thing. It can inspire you to emulate the great deeds of your forerunners. But it can also offer the balm of false comfort when what you really need is a stiff shot of reality.

U.S. leftists may have a particular weakness for romanticizing our predecessors. After all, most of our political victories have been fleeting and ambiguous, our heroes and heroines either little known (Wendell Phillips, Florence Kelley) or scrubbed of their radical thoughts and ambitions (Martin Luther King, Jr.) by the guardians of civil religion.

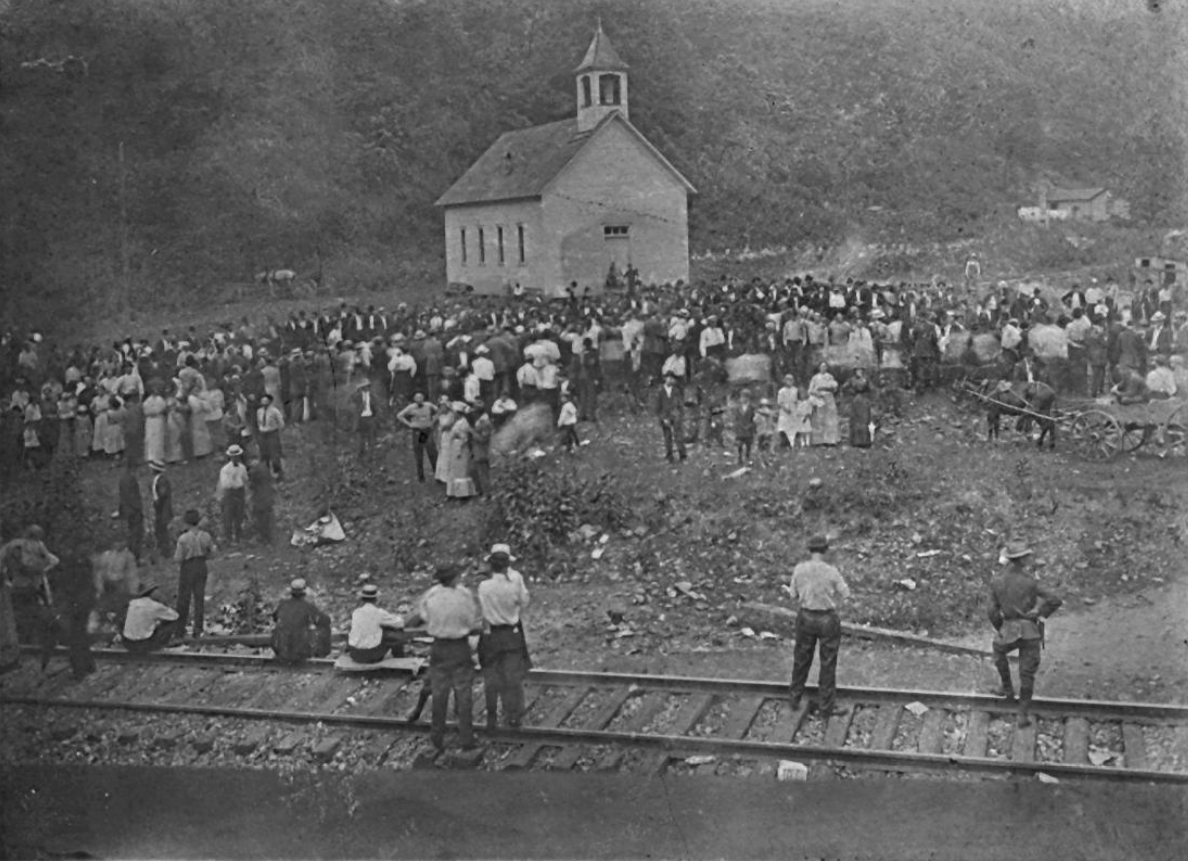

In her passionate essay about the rebellion she sees brewing in Appalachia today, Elizabeth Catte declares, “the way forward for the left, in my world, is through the past.” Her historical examples certainly played a pivotal role in the organized uprisings that won a measure of economic and political power for working-class people during the first half of the twentieth century. The unionists who waged bitter, often successful coal strikes in places such as Harlan County, Kentucky, and Mingo County, West Virginia, helped build the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) into a mighty force in what used to be one of the nation’s key industries. In 1946 the union compelled mine owners to finance a system of health clinics and pensions that were the envy of other industrial workers. UMWA president John L. Lewis also founded the Congress of Industrial Organizations, whose member unions went on to organize the biggest manufacturing firms in the nation—and injected the New Deal and the Democratic Party with a healthy dose of class consciousness.

But that spirit and strength depended on a political economy that no longer exists. The coal regime was the latest—probably the last— chapter in an often painful narrative of natural resource extraction from the mountains and high plateaus of Appalachia. It yielded great wealth for a few and poverty for the many, only occasionally mingled with decent jobs and benefits. In his brilliant book Ramp Hollow (2017), Steven Stoll provides a history of what he calls “the ordeal of Appalachia.” In contemporary West Virginia, he writes, politicians “continually menace” residents “with a false choice: health or jobs.” Due to the lower price of natural gas, as well as necessary environmental protections and falling demand from other nations, most coal-mining jobs have disappeared. Despite Donald Trump’s big promises, they are never coming back.

So the UMWA shrank. Nationally it has contracted to some 70,000 members (active and retired), down from a half million at its peak under Lewis. The remaining mine operators, with Republican support, slashed stipends for retirees. West Virginians became, once again, among the poorest and sickest people in the United States.

At the same time, voters there and across Appalachia recoiled from the cosmopolitan liberals who had become the national voices of a party once ruled by Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, Jr. Many gave credence instead to the siren songs broadcast by Fox News and delivered from the pulpits of their churches. As a result, Republican presidential nominees have carried both West Virginia and Kentucky handily since 2000, racking up huge margins in old coal counties. In 2016 Trump got 83 percent of the vote in Mingo County. Across the border in Harlan County, he pulled down a whopping 85 percent. There may still be “no neutrals there,” as Florence Reece put it, but there cannot be more than a hollow or two of union-loving progressives, either.

Catte knows this grim story. Still she claims that a different future is not only possible but is already underway. What is her evidence that a mass of Appalachians are busy creating a new movement to emulate the labor-centered one that disappeared decades ago? She mentions a brave Waffle House worker from Virginia who campaigned for a $15 minimum wage, a teacher from Mingo who took part in the recent strike against the atrocious conditions in the state’s schools, and a Democrat with a long Army career who ran an aggressively populist campaign for Congress in southern West Virginia last year but lost by thirteen points. We should root for these people. But, taken together, their efforts, even if multiplied tenfold, add up to a pretty meager resistance either to big business or the Trumpified GOP.

Unfortunately, Catte’s evocation of how such folks are using history to stoke their activism leans almost entirely on quotes about family members who took part in coal strikes thirty years ago. That is a kind of “continuity,” but since it is based on struggles that failed to change—much less revive—a declining industry, I doubt it is one that has the potential to “drive forward the present movements,” as she puts it with more hope than confidence.

For leftists to appeal to people in Appalachia and other parts of white rural America, they will have to talk in concrete terms about how to create secure jobs at decent pay, with the kind of benefits the UMWA once provided to its members. Rhapsodizing about the glory days of unionism will not convince those who, through no fault of their own, have missed out on the high-tech economic boom that has made metropolitan hubs such as the Bay Area, Seattle, and Northern Virginia so prosperous, if unequally so, and that has attracted a multinational workforce that votes reliably Democratic.

While Appalachians wait for that revival to occur, there is one lesson from the bygone days of working-class power that might help them stir or at least imagine a second coming of the left: build institutions that teach people how the world works and how they might change it. The UMWA accumulated clout at work and politics not just because it organized the men who did hard, essential work. The union also educated its members and their friends and families about who held power in the economy, which politicians were on their side and which were lying to them, and how to deploy a repertoire of tactics from shutting down a mine to effectively lobbying a state legislature.

A large and potent left once thrived in other parts of rural and small-town America too. Tenant farmers in central Texas railed at corporate moguls and the politicians who did their bidding. Their resentment and hope for redemption turned them first into backers of the Populists, then of William Jennings Bryan, and then of the New Deal. In 1908 and again in 1912, a higher percentage of Oklahomans voted for the Socialist Party of Eugene Debs, who hailed from a railroad town in Indiana, than did the citizens of any other state besides Nevada. Unless and until rural people build equivalents of the bygone farmers’ alliances, feisty insurgent newspapers, and craft unions of old, progressive Democrats today will be vulnerable to the charge that they are, or represent, culturally alien outsiders who threaten the values of “real Americans.”

Stories about the past can warm the heart and embolden the imagination. But only institutions can begin to turn those dreams into power.