In East Berlin, the Memorial to the Victims of Fascism and Militarism was a big attraction. Soviet-bloc tourists mobbed it, and by the mid-1980s visitors also included jittery NATO-country citizens on day-pass jaunts over the famous wall. Built as the New Guard House of Friedrich Wilhelm III, the Memorial had neoclassical, Doric-style columns under a low-peaked pediment. Within its echoing dimness, a clear prismatic block, Soviet-moderne, fragmented an eternal flame.

The draw was the changing of the guard out front. Orders were shrieked as young soldiers goose-stepped through a routine. You might see two of them, seemingly identical under their helmets, crack a surreptitious joke as one presented arms to the other. The crowd, nearly silent only moments before, surged abruptly toward the stamping boots to get a better look, while a line of police, as young and ostentatiously armed as the guards, swung truncheons, yelled, pushed the crowd back with viciously barking dogs. People in the crowd laughed, fell back, pushed forward.

The Memorial to the Victims of Fascism and Militarism gave chilling summation to the totalitarianism that had created it, in part because of its outrageous contradiction—claiming to condemn historic evils while making a triumphant display of them—and even more profoundly because the contradiction didn’t seem to be on anybody’s mind. In the liberal imagination, that sort of bald falsehood is supposed to invite public mockery, ultimately public rejection. And it is true that the wall came down. The so-called German Democratic Republic is no more.

Sightseers weren’t brainwashed into thinking military exercise is fitting remembrance of victims of militarism. Nor did they think police swinging sticks were harmless. They might have been thinking all kinds of things. Thinking was beside the point. In that sense the Memorial only took public history to its most grotesque extreme. From the Parthenon to Trafalgar Square, from the bronze Andrew Jackson of New Orleans to the gilded General Sherman of New York, from Arthurian legend to Serbian epic, history geared for a whole people usually celebrates founding moments, famous victories, hair’s-breadth escapes, tragic losses. It does not always promote fascism. It does tend, almost by definition, to rally nationalism. Thought and nuanced feeling get stifled by a thrill.

In a real democratic republic, where the whole people is supposed to be required to think, a different kind of public history is needed—lively and accessible, yet able to inspire without falsifying and to encourage consideration along with awe. So it is a deeply unhappy irony that the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, which since 2003 has celebrated on a grand scale our founding moment and enduring national law, obliterates dissent and pushes foregone and even false conclusions on its visitors. Undermining its own insistence on the importance of democracy to the United States, the Constitution Center reveals how readily public curators, however well-meaning, may seek to control rather than foster thought.

The first impression the Constitution Center makes is sheer size. Approaching from a distance on Independence Mall, you confront a high stone curtain against blank sky. The façade eschews any kitschy colonial or federal-era references. This is a temple—grave, stirring, and monumental. No one pretends anything happened here.

The next impression is a strange emptiness. On a recent Sunday morning, there was no line for the Constitution Center. Other attractions on the mall’s almost treeless expanse were drawing families of avid American-history tourists, splashes of color against the green. Near the south end of the mall sits the eighteenth-century Pennsylvania State House, with its famous cupola and bell tower (because the U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were debated and signed there, the building has been known for years as Independence Hall). Strung along the mall’s western edge are the National Park Service’s Visitor Center and the Liberty Bell’s low-slung viewing house. The eastern edge opens on the preserved and reconstructed old city—Carpenter’s Hall, and the site of Benjamin Franklin’s home, and brick buildings and gardens with appeal for history buffs and old-house fans alike. The imposing Constitution Center walls off the north end. That Sunday morning the tourists were already walking the shady streets, booking tickets for the ranger-guided tours of Independence Hall, and lining up for the Liberty Bell.

Once the few people hanging around outside the Constitution Center went in, the building looked eerily still. In the Center’s vast lobby, filled with natural light, emptiness expands. The ceiling soars with vaulting tetrahedrons. Visitors pass an elderly greeter evincing vague cheer in Wal-Mart mode and wander toward a distant ticket-booth island, wondering aloud what’s up, since there’s almost nothing to see but plaques praising private donors (“Patriots,” “Founders,” etc.), and a staircase sweeping to a broad, curving mezzanine lined by full-scale state flags hanging from the high ceiling. At the booth you and your fellow visitors are reminded that unlike National Park Service sites, where admission is included in your tax obligation, the Center charges. The ticket, as large as an open billfold, is an important-looking souvenir labeled “Delegate’s Pass”; you also get a red-white-and-blue paper wristband like those for drink tickets. But there’s still no visible enticement or obvious place to go. Friendly young ticket-sellers mention casually that the next show will start soon. Visitors gather that they’re supposed to see it. Another young employee stands in the distance, waiting to take part of the ticket. You troop past her.

You’ve entered a circular hall surrounding a cylindrical theater. While waiting for doors in the inner wall to open to the theater, you wander the circle, whose other wall is dedicated to impressionistic street scenes and maps of Philadelphia in 1787, year of the Constitutional Convention. Amid recorded bird chirping and period street noise, disembodied voices give actor-y exposition. “I grant you that times are bad, but . . .” “Have you seen the latest broadside by our friend Jupiter Howard of Long Island? . . .” The theater doors fly open automatically. You leave the eighteenth century and enter a dim space with steeply banked, industrial-chic seats around a circle of floor, where a presenter will stand and speak in the round.

In several recent visits, the seats were far from full. Once there seemed to be fewer than fifteen people scattered about the dark. A collage of period music and noise—bagpipes, clopping hooves, hymns, fiddles and fifes, black worksongs—is interrupted periodically by a recorded announcement of welcome, instruction, and prohibition: no eating or drinking, leave at the end of the show by going up the stairs, not through the lower entrances, etc. The coolly comforting female voice repeating the message, the automatically opening doors, and the podlike ambience make the place feel 1960s-futuristic.

The young workers close the doors. Lights dim further. The presenter enters through the last open door—that Sunday an African-American woman in a trim, man-cut dark suit and open-necked white shirt. A light shines brightly on her as she takes the center of the floor. “We . . . the people,” she begins, looking around at the spectators. Her voice and face blend immense wonder, delight, and curiosity. She has a big job to do. The presentation rests on her delivery of a script, supported by music and sound and by imagery on the high cyclorama.

The show is called “Freedom Rising,” and the presenter channels its relentless mood of triumph through facial expression, phrasing, and dynamics. This kind of recitation, with every gesture and glance memorized and controlled, was once an important part of American entertainment. The presenter is amplified, but her style is pre-amplification, pitched for the outdoor platform, the revue hall, the pulpit, and for an era when audiences with high tolerance for artificiality delighted in vocal nuance and expressive gesture. Near the climax, having asked rhetorically what will keep us together as a nation, the presenter starts pointing at various members of the audience, making eye contact and answering her own question: “You, sir . . . and you . . . and you . . . and you!” By the end she’s shouting her story, having climbed to an upper aisle, while images flash around a cyclorama running around the top of the theater and the music swells over military drumbeat. The cyclorama is pulling your gaze upward. Soaring music and rhetoric make you feel, willy-nilly, as if you are lifting your head not to see, but nobly, eyes fixed on an ideal about which you feel increasingly fervent. Whatever you may really be thinking, participation is made physical. “You!” are no mere spectator. “You!” are the star player in a thrilling historical tableau.

Which is the whole point. At the Constitution Center, democracy and the U.S. Constitution are synonymous. The Center makes the first three words of the document’s preamble, “We, the people,” both its theme and its brand. The Center’s tagline is “The Story of We, the People.” And this election season a special exhibit in the entry hall, swallowed by the surrounding emptiness, was entitled, awkwardly, “The Power of We.” (It consisted of big cutouts of Barack Obama and John McCain for photo-ops, a fast-moving LED-countdown to Election Day, and an invitation to write down a sentence you’d like to hear in the new president’s inaugural address. “I’m thinking Arby’s,” someone suggested.) At every moment, the Center frames “We” as a gathering in nationhood of the sort of ordinary, well-intentioned people who visit the Center, and from whose democratic spirit the Constitution has drawn, from the founding moment onward, history-changing power.

After “Freedom Rising” has identified “you!” as the main actor in “We,” it’s time for the next step. Amid desultory applause, the audience is again reminded to leave not by the doors at floor level but by mounting to doors around the aisle above the seats, as the next group is herded in. Outside the upper doors, you find yourself in a wide museum exhibit space encircling the top of the theater cylinder. In contrast to the proscriptions and forced emotion of the theater experience, here you’re turned entirely loose on a set of exhibits of the kind known to museum-goers as interactive.

Interactivity in museum exhibits is commonly described as democratizing. Instead of gazing at a work and reading a trained curator’s remarks about it, the interacting visitor contributes and completes. That idea is as old as the Metropolitan Museum’s Temple of Dendur and the Cloisters, where inhabiting a space is meant to enliven seeing and knowing. The full-scale, high-tech version is usually found not in art museums but in halls of fame and other centers for history, science, and culture not meant for contemplation only, needing imaginative, accessible ways of informing and inspiring.

The democratizing effect of interactive media might seem especially useful to a museum dedicated to what it claims is the archetypal narrative of democracy itself, with the ordinary person as chief actor. But at the Constitution Center, in the absence of any guidance, structure, or starting point, the freedom quickly becomes chaos. Here the “multimedia” that usually accompanies interactive museum exhibits means loud, distorted playback of recorded sound from many video monitors. Each soundtrack clashes and overlaps with others. Kids run to an exhibit to see what it does, then run to the next. Some adults take more time, especially with what turns out to be a set of displays reviewing Constitutional history from the confederation period to September 11, 2001, running in cases all the way along one wall. But there is at once too much to see in those cases and too little focus or substance, even for patient and interested visitors.

Meanwhile, with cacophonous interactivity, the Center is trying hard to dramatize its “We”/“you!” theme, the centrality of the ordinary person in giving life to the Constitution. Yet the exhibits are insipid. You’re provided with paper and pencil and prompted to write down what it means to be an American. You can vote for your favorite president: kids seem to like this setup, which involves mock voting booths and a staged “election night” TV report on video monitors above the booths, where a correspondent excitedly interviews pundits—which president will emerge tonight’s winner?—who turn out to be Gordon Wood and Richard Beeman, major real-life historians. (Wood notes in passing that the presidency was modeled on the eighteenth-century monarchy. It’s hard to hear, but nobody’s listening anyway.)

The importance of “you!” is taken to fantastic lengths in another bit, where visitors get sworn in as president. A faux chief justice on video, oddly depressed-looking, intones each phrase of the oath in the general direction of a space monitored by a closed-circuit camera. If you step into that space, another monitor displays you and the judge together, and you repeat after him. Teenagers throng to get sworn together, laughing uproariously, pressing a button to interrupt the process and start over. Meanwhile TV personality Ben Stein is answering mailed-in questions about the Constitution on a giant video monitor; there’s a jury box to sit in (because juries were invented by the U.S. Constitution?); there’s a towering sculpture made only of law books. It doesn’t do anything. An exhibit that draws kids only to disappoint them is a giant sculpture that resembles a Mattel “Hot Wheels” set: chrome roadways twist and turn with model cars and trucks stuck to them, while highway traffic roars. Nothing moves. Instead, on a crumpled surface resembling a loading-dock floor, you turn wheels to reveal fiscal data about state, local, and federal responsibilities for the nation’s roadways.

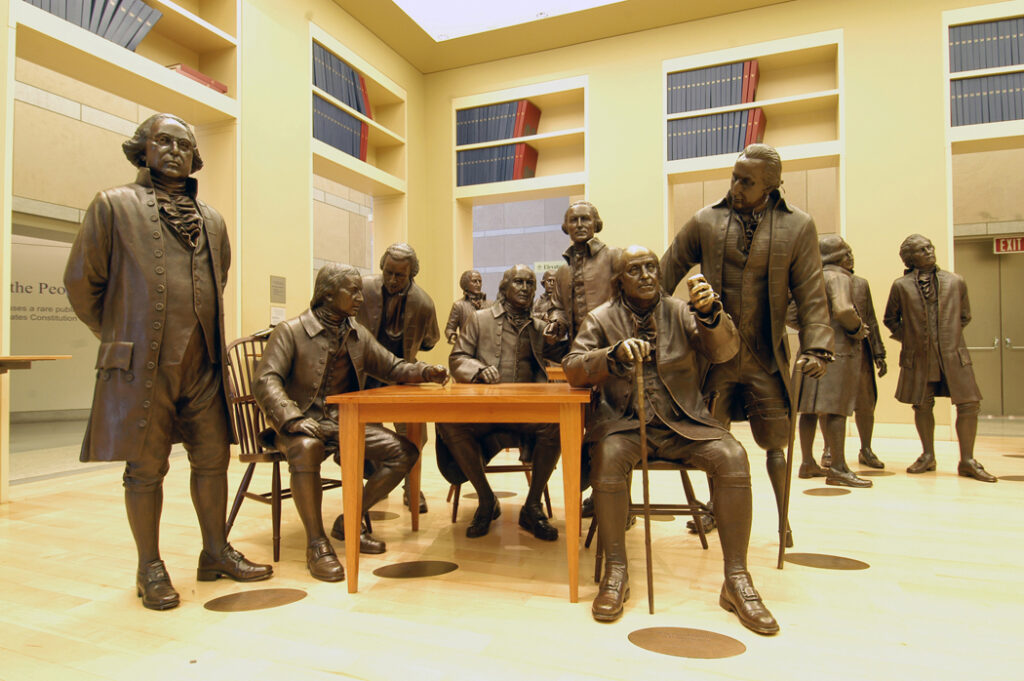

Moving toward the exit takes you through “Signers’ Hall.” Standing around this big room are statues of the Constitution’s framers, exactly life-sized and perfectly proportioned, frozen chatting with one another in pairs and groups. Are these ghosts, visiting our world? Are we flashing back to theirs? In any event, we’re all milling about together, famous founders and ordinary folk (in contrast to the real convention, which was kept so secret that windows to the chamber were sealed). Sidle up to Ben Franklin, drape an arm around Alexander Hamilton, get a grinning group snapshot with George Washington. They and “you!” mingle freely on equal terms. The Constitution’s essentially democratic nature is again made physical.

With nothing left to do, you leave Signers’ Hall and find yourself on the broad mezzanine under the high ceiling above the entrance hall. Vacant space curves around to the grand staircase back down to the lobby. Along this gallery hang those huge state flags, with dates of admission to the Union. For some reason there are also three video monitors high on one wall. They showed one day: C-SPAN, a tout to support the Center, and, no doubt inadvertently, the E! Channel, which happened to be airing the movie Showgirls.

What has inspired this mix of lavishness and shabbiness? Why is it so empty, in every sense of the word? Poor attendance gives a weird quality to both the hyper-controlled “Freedom Rising” show and the chaotic exhibit hall. The effort is flat-out indoctrination—yet nobody seems very interested. One might dismiss the whole thing as merely cheesy and dumb. But weak aesthetics and an apparent lack of operational precision are belied by the passion, prestige, and money that went into the Center’s creation. Somebody wanted this gigantic footprint to make a historical statement. The building’s assertive placement and modernist grandeur elevate the formerly underrated importance of the 1787 signing of the Constitution, counterbalancing the old site at the mall’s other end, whose name emphasizes the spirit of 1776 and American independence. Plaques off the lobby reveal that major figures in history and law are committed to the Center’s success. The Distinguished Scholars Advisory Panel is headed by professors Wood and Beeman. The Stanford Law Dean Kathleen Sullivan is typical of the big names in Constitutional law that grace the Panel. John Yoo joined when he was known as a conservative Berkeley law professor; he has gained notoriety since then in the president’s Office of Legal Counsel.

What did such high-profile, well-connected people of varying political leanings hope the National Constitution Center would become? What sort of programs did they imagine it presenting? At every turn, the Center breathlessly insists that “you!” are at once empowered and relied on, that every American is embraced, in a way unknown elsewhere, by “We.” Insistence keeps taking the form of pandering, flattering, and rallying, and it keeps falling flat.

The real problem may not be with the Constitution Center. It may be with the Constitution itself.

One of the deepest tensions in public thinking about the Constitution can be felt in the role that race plays in the Center’s narratives. Those narratives encapsulate for the general public what scholars know as a “consensus” reading of American history (though many reject the category as simplistic). The term has various meanings and shadings, but refers generally, as its name suggests, to shared American values, transcending political divides and social conflicts and making us, for all our differences, one nation. Breathlessness about the Constitution is a fairly crude manifestation of the consensus approach, which involves more than simple admiration. It has been supported by many of our more sophisticated historians, who argue that the Constitution put into legal operation essentially American commitments and attitudes, which, despite flaws and setbacks, tend to endow more and more people with freedom and equality.

Consensus history thus gives intellectual underpinning to an American liberalism that many self-described conservatives espouse as well. No serious presidential candidate, whatever he plans to do in office, questions the historical consensus, which is ultimately positive, ready-made for the sound bite, and by definition widely accepted. Most candidates, however, give consensus only a reflexive nod. A closer look tends to uncover conflicts. It was therefore an important moment not only for race relations but also for public attitudes about founding history when Barack Obama did far more than merely acknowledge the consensus reading of American history.

Obama gave his famous speech on race at the Constitution Center. The speech’s title, “A More Perfect Union,” is drawn from the phrase of the preamble following “We, the people,” and its approach to history tracks the narrative dramatized at the Center. In his opening, Obama described the signers, fancifully, as a roomful of men who “had traveled across an ocean to escape tyranny and persecution.” They “finally made real their declaration of independence” by devising and signing the Constitution and creating a nation. That picture makes the Constitution an expression of fundamental American ideas about liberty and equality, first put in practice, supposedly imperfectly, in the confederation of states that prevailed from 1776 to 1787, and given reality and stability only in the signing of the Constitution and the making of national government.

“Freedom Rising” tells that story too; fulsomely, so less believably. By the end of the show, the script has credited the Constitution with enabling “community”—“the day-to-day life of ‘We, the people,’” the presenter says—as if even day-to-day life had been waiting for the signing to come into being. A translucent box descends from the ceiling and encases the presenter while she invokes the likes of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, whose pictures are projected on the box’s scrim. Elvis gets there too: without the signers, no rock and roll. Projections and sound bites feature FDR, World War II, and Ronald Reagan telling Gorbachev to tear down that Wall. Even Richard Nixon does his bit, just by resigning. Gerald Ford is heard reminding us that “our Constitution works.”

The “stain,” as Obama and others have put it, on all that otherwise untarnished national glory is slavery. In “Freedom Rising,” the subject gets a special moment. “Slavery . . . !” the presenter intones grimly; the music slows, becomes moody. But unlike Obama’s far more forthright reading, which demands that we think about race itself, the “Freedom Rising” script somehow manages to avoid using the words “African” or “black” in connection with slavery. We hear only about “enslaved people.” We’re also reminded that slavery had long been a feature of civilization, and that the signers were “desperate” to create a nation. So with the stain acknowledged, it’s right back to the uplift. Because the story now becomes one of greater and greater inclusion, the mood can remain untouched by what we’ve just been supposed to consider. The exhibit hall, with more ample chronology, does tell of setbacks and struggles from slavery to civil rights and beyond. But there too, social progress is presented as inevitable because based on the Constitution, which spreads a fundamentally American democracy throughout America and the world, qualified by one stain and one stain only.

With everybody appearing to have considered, as one, the horror of the stain, the consensus holds. Does it hold, in that sense, because of the stain? Obama’s “A More Perfect Union,” having laid strong claim to the consensus, made more trenchant and challenging points about the harrowing effects of slavery and racism in America than the Constitution Center’s narratives probably ever will. Yet Obama’s challenge, too, rests on unshakable faith in a fundamentally American ethos of democracy supposedly at work, albeit imperfectly, in the signing. Celebrating a democratic national consensus, “We” get together and give ourselves goosebumps.

You wouldn’t know it by listening to campaign speeches or by visiting the Constitution Center, but there is no agreement about consensus history or the democratic purpose of the Constitution. A hundred-year war rages in history circles over what was really going on at the founding when it comes to equality, liberty, and law, and how those relationships affected the writing and ratification of the Constitution we live by every day. This war stays out of public view in part because it does not turn solely on issues made notorious in recent decades as “multicultural”—slavery, female disenfranchisement, race and gender inequality; also the ignored contributions of women and minorities—or, at the other end of the scale, on conservative philosophies like “originalism,” in Justice Scalia’s preferred term, where interpretations that promote social progress are deemed outright distortions of Constitutional intent. Those dissents are famous. This war involves facts even more deeply disturbing to our shared faith in the American values of the founding moment.

Delegates came to Philadelphia in 1787 not to form a democracy but to redress “insufficient checks against the democracy,” as Edmund Randolph of Virginia put it in his opening remarks, which framed the convention’s agenda. Both Alexander Hamilton of New York and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, sworn enemies, rallied fellow delegates to rein in “an excess of democracy” by forming a national government. It is sheer fantasy to say that, having been shakily established in the Declaration, “democracy stumbled” (as “Freedom Rising” puts it) during the confederation period, and so had to be restored for all time by the Constitution. To the delegates, precisely the reverse was true. Rivalries that flourished before and after the convention—Southern planters vs. urban financiers; nationalists vs. state-sovereigntists—were subsumed in common effort to push democracy back. Those men chatting in Signers’ Hall weren’t keeping women and minorities out of an otherwise democratic republic. They were framing a republic to limit the democracy recently taken up by white men.

If those remarks sound novel and bizarre, that’s the novel and bizarre thing. Such a critique once enjoyed wide currency, and though little discussed publicly now, continues to be part and parcel of all serious, informed debate about American founding history. Today’s academic consensus historians—towering examples include Wood (the chair of the Constitution Center’s Advisory Panel), an eminent professor of history at Brown, and Edmund Morgan, professor emeritus at Yale—achieved their success by addressing the obduracy of those facts about the founders’ efforts. They have opposed the long sway of a competing historical viewpoint, anti-consensus, put forth by scholars like Charles Beard, Carl Becker, and Merrill Jensen, “progressive historians” whose reputations have declined. In the first part of the last century, the progressive historians looked closely and publicly at the signers’ elitism; the powerful democratic impulses and activities of ordinary, less-enfranchised white men; troubled relationships among political equality, economic fairness, and liberty; entrenched sectional conflicts; and the question of whether the framers were constituting a national government, at least in part, as a counterrevolution to shore up elite interests.

Those historians focused, in other words, on class. They found themselves at least as interested in a founding struggle among Americans as in a founding struggle against the British Empire. Some of them saw the founders’ opposition to democracy arising from financial self-interest, which the signers pursued by constituting a national government that favored elite interests. Some could be baldly elitist themselves; some tried to locate anti-elitism in unlikely places.

Like all schools of thought, the progressives made many now-evident mistakes, were excessively influenced by social and political trends, and fell out of favor when moods changed. Amid new moods, and with new scholarly arsenals, the consensus historians who absorbed and surpassed them have rejected class warfare among Americans as a fundamental element in the founding story. In the academy, certain progressive-history assumptions do thrive—right-wingers complain they even rule—but in public history, quashing class interpretations of the founding period has been decisive not because the public has been persuaded, after careful thought, that class turns out not to be important to the founding after all, but because the public mind seems committed to not thinking about class.

The unfortunate result is the absence of any realism, at the Constitution Center and elsewhere, about founding purposes.

And yet the historians who enable the assumptions most convenient to cheap celebration are not themselves cheap. They are among our most adept and learned professors, with the highest-profile careers, often admirably committed to writing both for peers and for general readers. Nor do they march in lock step. Scholarship has led each to a personal interpretation.

Edmund Morgan, for example, now in his nineties, embodies the centrist liberalism of the consensus view. Among the best-known of his many important works are the scholarly yet readable The Stamp Act Crisis, The Puritan Dilemma, and American Slavery, American Freedom, as well as a lucid overview for general readers, The Birth of the Republic. Early on Morgan defined his intellectual enemies as, on the one hand, revisionist neo-Tory historians who were questioning the purity of the American tax resisters’ motives, and on the other, American progressives like Beard, who seemed to ascribe venal financial self-interest to the Constitution’s framers.

Morgan built a body of work dedicated to showing utter consistency of principle on the part of American patriots, from the first protests through ratification. His sensibility, and that of the informed consensus as a whole, may be glimpsed in this remark from The Birth of the Republic, in which he acknowledges the self-interest Beard had pointed to, while absorbing it in an optimistic consensus reading:

In each case self-interest led to the enunciation of principles which went far beyond the point at issue. In each case the people of the United States were committed to doctrines which helped to mold their future in ways they could not have anticipated. At the Constitutional Convention much the same thing occurred. The members had a selfish interest in bringing about a public good.

Gordon Wood, a generation younger than Morgan, follows some of the old progressives in defining the American Revolution as socially radical. Wood means by “radical” something different from what leftists mean. In The Radicalism of the American Revolution, as well as in many engaging articles for The New York Review of Books, Wood has put a wide frame around the founding. For him the Revolution was not accomplished until the age of Jackson, when social mobility, small-scale enterprise, and a rowdy, unrefined spirit brought America into its own. Wood sees true American radicalism not in any failed or suppressed effort at populist egalitarianism, but in ending traditional forms of social deference and making a dynamic modern society. He doesn’t need to explain away the elitism of the famous founders, which had once led him, in progressive vein, to label the Constitution “aristocratic.” In Wood’s most mature work, the Revolution didn’t end until those founders had been left behind and America had settled on the reasonably liberal, restlessly capitalist, socially fluid society that eighteenth-century citizens wouldn’t have recognized.

For all the provocative nuance possible within the consensus, its tendency is to give the public a false impression that progressives’ discomfiting ideas about the role of class in our founding have been permanently superseded by more judicious, less partial scholarship. There is in fact a persuasive competing view, presented with great verve and insight by historians associated with the New Left—Jesse Lemisch, Staughton Lynd, Dirk Hoerder, and others. They have uncovered the eighteenth-century radical movement of ordinary and unenfranchised people who equated democracy with legislating social fairness and forcefully dissented, often with rowdy crowd actions, from elite monetary policy and unfettered capitalism alike. Consensus historians define such movements as anachronistic, at best marginal. That notion, rarely closely examined, is soothing for more-or-less liberal middle-class history buffs. It also gives support to the deadening self-congratulation and outright falsehood on display at the Constitution Center. In academic history, a consensus view may be arrived at. In public history, consensus is coerced.

So complete, in fact, is the public success of the consensus view that smart new books hoping to shake it up for general readers are not widely known. The one book on the Constitution that has enjoyed strong sales in recent years is America’s Constitution: A Biography by Akhil Reed Amar, a thick consensus work, leading the reader through a familiar if unusually detailed celebration of the document as establishing unprecedented degrees of popular sovereignty. The press has largely ignored neo-progressive books that anyone interested in the story behind the Constitution would also have to read: Terry Bouton’s Taming Democracy and Woody Holton’s Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution. Gary Nash’s The Unknown American Revolution, another work of lively dissent, actually did get some attention—even some criticism from the consensus side—and is available, pleasingly enough, in some history-tourism gift shops (though not at the Constitution Center’s).

Bringing to life the importance of the eighteenth-century populist movements, dismissed by consensus historians, which avowed true economic radicalism, all three authors bring class struggle back to the founding story, and with it some drama and personality. Without rehashing Beard and Becker, they offer fresh, well-argued challenges to the notion that the famous founders were motivated by democratic instincts, or that their work tended inevitably toward democracy regardless of their instincts.

Each writer takes an idiosyncratic view. Bouton’s is pessimistic. His unique understanding of founding-era public finance and its importance to ordinary people’s lives (far surpassing that of Amar, for example, in his uselessly complacent reading of Article Ten), makes a major contribution, and Bouton shrewdly distinguishes genuine working-class populists from anti-federalists, who seemed to support the populists but really opposed the Constitution for their own elitist reasons. His bleak conclusion is that any potential for working-class democracy came to an end in the suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion. Holton, in startling contrast, sees those same working-class democrats as saving, via the amendments, a document devised for plutocratic reasons, thus at the last minute making the Constitution the protector of the downtrodden we celebrate today. Nash, author of many important academic books on the underappreciated contributions of laborers, artisans, women, and minorities in the Revolutionary struggle, offers general readers a bustling overview of the populism of the period, in all its many aspects, from the Stamp Act crisis through ratification.

Many questions persist to challenge progressive history. They go back at least to Richard Hofstadter’s compelling chapters on Beard in The Progressive Historians. What did people in the eighteenth century really man by “democracy” anyway? How truly limited was the franchise? Were there really enough unpropertied men to form a huge non-voting bloc? Were the famous founders really out to line their own pockets? The exciting thing about Bouton, Holton, and Nash, among others, is that they bring persuasive new thinking to those questions (they’ve absorbed Hofstadter’s skepticism and know how he could go wrong, too). Yet few general readers who considered Amar’s book on the Constitution a must-buy are likely to have heard of Holton’s, despite its being a National Book Award finalist. In the public sphere, consensus history always gets the last, numbing word.

Is it imaginable that any history-tourism destination would want to admit complexities that would send visitors home more troubled than satisfied, more questioning than answered, wondering how we got here, where we’re going, and what it would take to develop a personal point of view on the whole thing?

Possibly not—but if John Yoo, executive-branch apparatchik, can share space on the Constitution Center’s Advisory Panel with Gordon Wood, why can’t Woody Holton? A less stiff and pushy presentation than “Freedom Rising,” fired by competing ideas, might dispense with hand-on-heart nation-worship and find some real drama—even suspense—in the opposition to the Constitution that prevailed during the founding, from the planter elitism of Patrick Henry, who identified liberty with the sovereignty of Virginia, to the rugged egalitarianism of little-known, equally idiosyncratic elected leaders, like the Pennsylvania farmer Robert Whitehill and the backcountry preacher Herman Husband, who objected not to national government itself but to what they saw as the Constitution’s suppression of working-class democracy. Greater forthrightness about slavery and less patronizing squeamishness about race would also help liven things up.

Ideas for exhibits might be sparked by unyoking the user-centric nature of interactive functionality from the dull message that the country, too, is by nature user-centric. A hands-on way of re-devising some of the more startling solutions proposed and fought over by the convention delegates (and quickly passed over by “Freedom Rising” as if manifestly absurd)—obliteration of the states, limited monarchy, unicameral legislature—could be both fun and informative. Even a video showing consensus and anti-consensus scholars hotly debating the real meaning of the Constitution would be more compelling and incisive than Ben Stein talking to a camera.

Debate, which gave rise to the Constitution, and which it protects, is what’s really missing from the Center. Where better to hold public discussion of, for example, the strange fact that there’s a surveillance camera visible in the Independence Hall belltower, commanding the mall from where the Liberty Bell once rang? If calling the place Independence Hall now differs appreciably from calling snapping guard dogs and goose-stepping troops a Memorial to the Victims of Fascism and Militarism, it would be reassuring to hear why, and to hear it at a place dedicated to constitutional issues.

What the Constitution Center keeps trying to beat into our heads is that our nation differs categorically from all others. But national identity always claims categorical difference. To make an American difference real and believable would mean actually doing something different—and that would mean expecting more from “We, the people” than the desire to push a button and admire ourselves, yet again, on video. Some of the founders were suspicious of democracy because they viewed the mass of American people as incapable of making independent judgments. Overbearing national narratives try to rob people of that capacity, abusing both history and the citizens who come, of their own free will, to learn about it.

So it makes a pleasant change, after visiting the Constitution Center, to walk the length of the mall to Independence Hall. National Park Service rangers give tours on a demanding schedule, and while things move along briskly, each tour has a different quality, because each ranger is passionately informed. After looking around the State House yard, where mass meetings took place throughout the eighteenth century, and before entering the chamber that the Pennsylvania Assembly loaned to delegates of Continental Congress, and then, eleven years later, to those of the Constitutional Convention, each tour group gathers for a few moments of orientation. The rangers ask some basic questions, and handle without condescension responses that show a wide range of historical interest and sophistication within any one group and from group to group. The rangers are not delving into a lot of dissenting history. We’re all in the group for our own reasons, and it turns out to be somebody’s job—our federal government’s!—to help us gain whatever degree of understanding we seek.

Something big did happen a long time ago, twice, in this building. It’s good to stand again in the old chamber, always surprisingly small, and remember that it was real.