“Save America.” “Take the country back.” “Armed and dangerous.” “Lock and load.” Such are the slogans of the right-wing populist resurgence that began in 2008.

The new populism embraces members of the Tea Party, who object to what they see as confiscatory taxation, excessive government debt, and assaults on the right to bear arms; fans of Sarah Palin, who assails the Obama administration and the Democratic Party for being out of touch with what she defines as the lives and aspirations of ordinary Americans; and some Republican elected officials. They not only reject Obama administration policies, and political liberalism in general, but also cast their rejection in questing, confrontational language as an epic battle for the soul of American democracy, which they accuse liberalism of defiling.

In the face of this rejection, liberal voices in the press largely have failed to illuminate the new right-wing movement. Frank Rich, a columnist for The New York Times, applies epithets (“cowed” Republican politicians bowing before “nutcases”), makes airy dismissals (“the natterings of Mitch McConnell, John Boehner, Michael Steele”), and, using scary metaphors (the grass-roots right as “political virus,” “tsunami of anger,” even “the dark side”), warns of threats to civilization itself. The historian and critic Jill Lepore, in an otherwise thoughtful New Yorker article on a Tea Party rally in Boston, becomes uncharacteristically bemused when it comes to interviewing Tea Party members directly. Chip Berlet, asking his readers to view with compassion what he and others have called right-wing American populism, reveals an even deeper prejudice. He writes in The Progressive:

If we dismiss them all, we not only slight the genuine grievances they have. We also push them into the welcoming arms of actual and dangerous far rightists. . . . much of what steams the tea bag contingent is legitimate. They see their jobs vanish in front of their eyes as Wall Street gets trillions. . . . They worry that their children will be even less well off than they are. They sense that Washington doesn’t really care about them. On top of that, many are distraught about seeing their sons and daughters coming home in wheelchairs or body bags. . . . they stir in some of their social worries about gay marriage and abortion, dark-skinned immigrants, and a black man in the White House.

Berlet seems to mean to be fair to the political preferences of many working- and lower-middle-class white Americans. Yet he asks readers to consider what Tea Partiers “see” and “sense”—not think, not even surmise. He indulges a churning set of “worries” about dark-skinned immigrants, a black president, abortion, and gay marriage, which he lists as qualitatively identical for being, to him and his readers, delusional. He even patronizes distress over dead and wounded children. With every sentence in which Berlet and his fellow writers depict right-wing populists for liberal readers, they can only make the populist case: liberalism is elitism.

That unintended effect points to larger problems in the long, troubled relationship between populism and liberalism. Because populism seeks, ostensibly, to enshrine and advance the rights and hopes of ordinary people, and because liberalism believes itself to be those rights’ best protection, populism’s rightward allegiances can be distressingly counterintuitive for liberals. Why, liberals wonder, don’t populists vote their economic interest? Liberals have long been asking about the white working class’s tendency to vote for Republican candidates, whose programs benefit the wealthy, and to reject the Democrats, whose programs, liberals keep insisting, benefit the working class. Liberals look wistfully to the New Deal days, when their predecessors banded together with populists and elected Franklin Delano Roosevelt president four times.

Yet the New Deal was a brief and possibly exceptional period, full of changes so big and important that it tends to block our longer-range historical view. American political and cultural life has more often involved mutual incomprehension and outright hostility between liberalism and populism. Repeatedly in U.S. history, the two have defined themselves publicly, as they are doing now, by rhetorical rejection of the other. Both ways of thinking may be fundamentally American, but that also may be all they share.

An important moment in the opposition of liberalism and populism, salient for today’s public commentary, came at the end of the nineteenth century, when populism had its big break in party politics with William Jennings Bryan’s rise in the Democratic Party. The moment is revealing because the populism of that period was not rightwing but left. Yet the main populist assault, just as today, was on common liberal modes of discussion, debate, and expertise. Many liberals of the period, for their part, disdained left-wing populism with no less ferocity than today’s liberals disdain the right-wing kind.

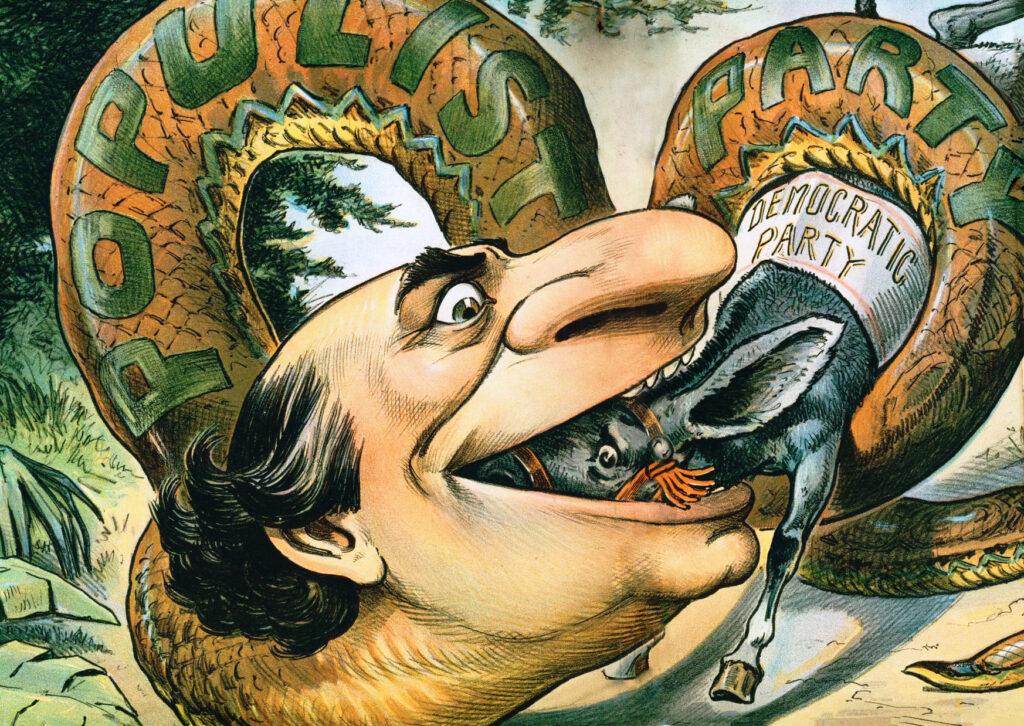

The populist movement began in the late 1880s, when the People’s Party, centered on small farmers in Kansas, organized a powerful resistance to big-time Eastern banking and railroad interests. The farmers made common cause with the young labor movement, which was attracting both urban and rural members. Populism spread in the West, and in 1892 James B. Weaver, a populist third-party candidate for president, carried Colorado, Kansas, Idaho, and Nevada. In 1896 populists moved into mainstream national politics by supporting Bryan as a candidate for the Democratic Party presidential nomination. Bryan always remained a Democrat, and he was sometimes careful to distance himself from the Populist Party, but he made Midwestern populism the basis of an astonishing career.

The populism for which Bryan became a larger-than-life national spokesman was a left-wing movement in that it sought radical social change, fostered by government, favoring labor over capital. Populists wanted to organize the American laboring, artisan, and small-farming classes around a goal of economic and political equality. They called for abolishing national banks, instituting a progressive income tax, enforcing an eight-hour workday, and nationalizing the railroads and telegraphs, the largest corporate sectors of that era. Making what today are called social-justice demands on big government, they sought to use state power to regulate commerce and restrain the abuses they saw as inherent in corporate wealth.

Agrarian and labor populists of the turn of the last century did not, as a rule, embrace Marxism. While some strains of Kansas populism did inspire radical elements in the labor movement— as it would later develop in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or Wobblies) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO)—and while other strains had resonances for the American Communist Party’s expression of the Popular Front of the 1930s, the Kansas movement did not envision itself a vanguard in a worldwide revolution for a dictatorship of the proletariat, a next and better stage in human development. That the producer, not the consumer, should benefit from society’s efforts was especially and rightly American, populists believed. And populists held that an America true to what they defined as its democratic origins must always favor ordinary laborers over investors and small farmers over well-heeled bankers.

So along with their left-wing ideas about the potential of government to ensure economic fairness by restraining wealth and regulating commerce, populists advanced a conservative, even nativist, criticism of the corporate ethos. They accused corporate hegemony of being innovative, departing from what they saw as the small-scale, family-focused ethics of the past; and un-American, since the past they admired involved the nation’s founding and early expansion. Populists were not opposed to enterprise, but in keeping with their admiration for the pioneer experience, they preferred the open spaces and even the cities of the Midwest and Rocky Mountains to the old urban centers of privilege, banking, and luxury back east. They deemed advanced formal education and its resulting expertise tools for keeping ordinary people out of the halls of power. Populists revered practical know-how, the common sense and hands-on experience of the worker, farmer, and small businessman.

By contrast, progressives, as liberals often were known (and there were many kinds of progressives, some adopting elements of populist rhetoric, others in their own way conservative), by and large wanted regulation of big business, not nationalization. Progressives, like populists, attacked Wall Street for greed and plutocracy, but as their name suggests, progressives hoped to move American society forward, not backward to an imagined pioneer democracy. Like liberals today, they wanted government to manage corporate capitalism for the greater good, not to dismantle it; they wanted the producing class supported and improved, not given wholesale charge of government; and their hopes for social progress lay specifically in advanced formal education.

Woodrow Wilson was one such progressive. In 1908 he was president of Princeton and was beginning to reject the conservative pro-business interests that had supported him politically. Yet even as Wilson attacked the corporate concentration of wealth and became increasingly liberal, he saw Midwestern populism as undermining real social improvement. “Would that we could do something, at once dignified and effective, to knock Mr. Bryan once and for all into a cocked hat,” he told a railroad magnate. And while Wilson worked, as president, to restrain corporate trusts, he was inveterately suspicious of the more radical aims of the labor movement.

Wilson was in many ways a conservative progressive (he shared some of the populist nostalgia for an earlier America), but others more liberal than he also attacked populism. A scabrous, funny attack, closer in today’s terms to the invective of the comedian Bill Maher than to Rich’s, came from the important progressive leader William Allen White in this 1896 Twain-influenced parody of the anti-intellectualism of the Kansas populists:

We have an old mossback Jacksonian who snorts and howls because there is a bathtub in the state house; we are running that old jay for Governor. We have another shabby, wild-eyed, rattle-brained fanatic who has said openly in a dozen speeches that ‘the rights of the user are paramount to the rights of the owner’; we are running him for Chief Justice, so that capital will come tumbling over itself to get into the state. We have raked the old ash heap of failure in the state and found an old human hoop-skirt who has failed as a businessman, who has failed as an editor, who has failed as a preacher, and we are going to run him for Congressman-at-Large. He will help the looks of the Kansas delegation at Washington. Then we have discovered a kid without a law practice and have decided to run him for Attorney General. Then, for fear some hint that the state had become respectable might percolate through the civilized portions of the nation, we have decided to send three or four harpies out lecturing, telling the people that Kansas is raising hell and letting the corn go to weeds.

Throughout the piece—called “What’s the Matter with Kansas?”; the social critic Thomas Frank borrowed the title for his 2004 book on the shift from left-wing to right-wing populism—White lampoons what he presents as populism’s sheer lowbrow idiocy. But the joke is bitter because White was anything but a defender of the Eastern corporate elite. He was a Kansas journalist and publisher; he supported business and capital but opposed trusts and monopolies, and he worked for women’s suffrage, workers’ compensation, inheritance taxes, and a raft of other liberal policies. White lived long enough to support establishment-progressive efforts from Theodore Roosevelt’s trust-busting to Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations to major elements of the New Deal (though he never voted for FDR). White lived the classic American liberal dilemma, warning of the dangers of plutocracy while disdaining the yahoos. It was the nativist, left-wing populism originating in his home state, the kind with which Bryan was synonymous, that he could least abide.

What populism would not abide became clear with a speech that Bryan gave at a climactic moment in the 1896 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, well remembered today as his “cross of gold” speech in part because he went around delivering it to enthusiastic crowds for decades afterward (he even made a recording of it in 1921). That was when conventions were conventions. Platform points were fought out on the floor, issues passed by acclamation, and candidates could be pushed high or brought low by delegates’ vocal approval or disapproval.

The major platform point at the Chicago convention was monetary policy. Populists wanted to end the gold standard. Pegging currency to the value of gold favored banking and corporate interests, forcing small borrowers, who were among the populists’ main constituents, to pay on the value of a loan when taken, not the value to which it would depreciate over time. Depreciation benefited farmers, small businesspeople, and laborers, since the real value of mortgage and other interest payments goes down with inflation. The 1890s were a decade of economic depression and widespread foreclosure; our current crisis makes it easy to see why many ordinary Americans then viewed the loan business as a scam to place them in peonage to their creditors. They saw the gold standard as one of that scam’s best tools.

Populists therefore proposed bringing back silver as a secondary standard. They wanted what eighteenth-century advocates of paper currency and legal-tender laws had wanted: a generally usable medium of exchange, one that would require lenders to accept some degree of depreciation, especially during difficult economic times. Money itself would incorporate a kind of debt relief and leveling of the playing field. But Bryan’s tactic in Chicago was not to make a well-considered argument for what was called bimetallism. The delegates already had largely rejected the Democratic incumbent Grover Cleveland’s loyalty to the gold standard. The concluding image by which Bryan’s speech is

known—“You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold”— is emblematic of his unabashed way with an intensely emotional attack. In terms presaging those used by populists today, he said:

Our silver Democrats went forth from victory unto victory, until they are now assembled, not to discuss, not to debate, but to enter up the judgment rendered by the plain people of this country.

Then as now, the hottest blast of populist rhetoric was directed less at specific policies than at elites’ dismissal of ordinary people’s judgments, determinations, and desires; at what populists saw as the undemocratic, un-American claim to superior expertise; at forestalling decisive action through discussion and debate. With Bryan and his allies having ascertained the wishes of ordinary people, discussion and debate must cease. His plain people do not live in the East:

Ah, my friends, we say not one word against those who live upon the Atlantic Coast; but those hardy pioneers who braved all the dangers of the wilderness, who have made the desert to blossom as the rose—those pioneers away out there, rearing their children near to nature’s heart, where they can mingle their voices with the voices of the birds—out there where they have erected schoolhouses for the education of their children and churches where they praise their Creator, and the cemeteries where sleep the ashes of their dead—are as deserving of the consideration of this party as any people in this country. It is for these that we speak.

Bryan discerned in the frontier and small-town experience something fundamentally more American than anything in the centers of elite policy—“real America,” as Palin has put it. And Bryan’s pioneers appear to have modest demands. They ask only for their rightful place at the big table. Yet the modesty justifies an unconditional confrontation. Straight from the poetry of prairie birdsong and schoolhouses and cemeteries, Bryan makes an outright declaration of war:

We do not come as aggressors. Our war is not a war of conquest. We are fighting in the defense of our homes, our families, and posterity. We have petitioned, and our petitions have been scorned. We have entreated, and our entreaties have been disregarded. We have begged, and they have mocked when our calamity came. We beg no longer; we entreat no more; we petition no more. We defy them!

By the time Bryan brought the speech to its final figure, with labor and mankind a single holy body on the crucifix, the delegates were so overcome that they whipped off their coats and threw them high in the air, made silver a key position in the Democratic Party platform, and nominated Bryan, at only 36, their candidate for president. The liberal mode of seeking compromises between labor and capital—represented by Bryan’s nearest competitor in Chicago, Richard Bland—was out.

Bryan lost to William McKinley and spent the rest of his long career as perhaps the most powerful divider in American political history. He began the tradition of consolidating strength by losing elections and threatening breakaways, a tradition that has inspired Strom Thurmond, George Wallace, Jesse Jackson, Pat Buchanan, Ross Perot, Ralph Nader, and, possibly, Palin. He lost in 1896 by running against gold, in 1900 by running against imperialism, and in 1908 by running against trusts. He used Midwestern populist clout to build an insurgent coalition that, for a time, was a force in the Democratic Party. His constituency was so big and fervent that his endorsement became priceless, and he used it to influence platforms even while he became a well-paid superstar on the lecture circuit. Palin may be hoping to play a similar role in today’s Republican Party, and some party strategists no doubt worry that she will induce them to recreate Bryan’s losses for his Democrats. In exchange for one of his endorsements, Bryan served nominally as Secretary of State for a reluctant Wilson, but, like Palin, he could not have accomplished his ends in elected office. His main occupation was rallying, not policymaking. On whistle-stop tours, in tents, and at gatherings of every kind he made speeches, long ones, hundreds of them. Palin accomplishes similar goals with books, social media, and occasional appearances.

Both Bryan’s words and his tone express uncompromising defiance of the deliberative, intellectually sophisticated liberalism of White, Wilson, and their ilk. All he saw in their privileged expertise was dismissal, mockery, and disdain, an assumption of superiority not found even in pro-business conservatism. When today’s right-wing populists make threatening remarks like “lock and load” and talk about taking the country back, they’re applying the method that Bryan perfected. The war he kept declaring was a moral one for transcendent virtue and self-evident good, beyond debate and petition, beyond the win-some, lose-some, art-of-the-possible quotidian. Ultimately his themes were spiritual. On the circuit many of his best-loved speeches were not political at all, but purely religious, true evangelical sermons. While his political targets often were conservative corporate interests, the evangelical mood in which he expressed himself involved a fundamental rejection of liberal ways of thought and rhetoric.

The historian Richard Hofstadter, in his seminal books Anti-Intellectualism in American Life and The American Political Tradition, rates Bryan’s intellectual fluency so low that the chapter on Bryan in Political Tradition is at times laugh-out-loud funny. Hofstadter joins White in viewing Bryan’s populism as a clever expression of dangerous idiocy. It’s not clear how fair that assessment is. Hofstadter’s was a unique sensibility, influenced in one way by serious Marxist scrutiny and in another by the refinements of high culture. He was brilliantly skeptical of everybody from Andrew Jackson to FDR, but almost intemperately hostile to all forms of evangelicalism, which he detailed with enormous distaste, in many books, as a defining streak in American cultural and political life.

The anti-intellectual evangelicalism that Hofstadter saw as inherent in populism and that so upsets liberals today may be witnessed in Bryan’s opposition to teaching Darwin’s theory of the evolution of species, a conservative position that brought Bryan’s career to a dramatic end in the famous Scopes “monkey” trial. Bryan’s antipathy toward teaching evolution—really toward evolution itself—might seem to foreshadow populism’s fateful shift from left to right, when populists began promoting cultural conservatism instead of economic fairness. That is the shift lamented by writers such as Frank and traced by Michael Kazin in The Populist Persuasion, Rick Perlstein in Nixonland and Before the Storm, and Joseph Lowndes in From the New Deal to the New Right.

For Bryan, however, there was no shift. His anger at corruption in entrenched capital was identical to his anger at blasphemy in Darwin’s theory. In Bryan’s populism, the plain people are by definition the last arbiters of truth. On monetary policy, the people rendered their judgment against gold and in favor of silver, and Bryan delivered that judgment to the establishment. On the nature of creation, the people judged against evolution and in favor of the literal truth of the Bible; Bryan delivered that judgment, too. His argument against Darwin’s theory also had an economic element. It outraged his sense of justice to imagine humanity ascending by the survival of the fittest and the destruction of the least fit, the strong forever preying on the weak, the endless quest for dominance he associated with human hatred, greed, and corruption. He saw scientific Darwinism and social Darwinism as one and the same, and he called for a society and a conception of creation based on love, not hate.

That position was complicated by the angrily uncompromising tone, anything but loving, that he took and encouraged his supporters to take. The line between prairie birdsong and explosion was always a thin one for Bryan; that thinness may have made his career as a speaker and a leader. His politics of a non-political populism, advancing itself on religious and social grounds, stands for self-declared, self-defined goodness. It equates that goodness with the ordinary, working-class, democratic values that it declares fundamentally American. In protecting those values, it announces itself ready, at a moment’s notice, to fight to the death the arrogant social superiority that it views as institutionalized in liberal thought.

Why do populists see arrogance institutionalized only in liberalism? Can’t populists discern at least an equal degree of arrogance in conservatism? Anyone who finds a practical way to address that question should become a Democratic Party strategist. In 2000 Al Gore told voters clearly and repeatedly that Republican policies were intended to benefit the richest one-tenth of one percent of Americans. George W. Bush called the math fuzzy, but it’s far from clear that voters who chose Bush did so because they agreed with him that Gore’s numbers were lacking. As Rich and others have noted, many in the Tea Party movement don’t like Bush or his dynastic roots. The last administration’s use of government to shore up power and enrich those it favored are part and parcel of the Tea Party complaint. But most in the Tea Party would choose Bush again, not Gore.

A common liberal theory for populism’s war on liberalism is sheer paranoia on the right. The theory is used to explain racism, nativism, and any other prejudice that liberals oppose. It seems to be reinforced by those deliberate efforts by right-wing Republicans, beginning in the 1960s, to connect the party to working- and lower-middle-class loathing of social changes dictated by federal law.

The paranoia theory’s origin is Hofstadter’s 1964 essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Hofstadter argues that anti-intellectual impulses often come together in lurid conspiracy theories that defeat rationality in politics. He quotes Bryan’s silver populists of 1895 on an international gold ring supposedly trying to control the world; he quotes Joseph McCarthy on the alleged infiltration by communists of the highest reaches of U.S. government; he quotes those who believed Roman Catholics plotted to put the Pope in secret authority over the U.S. Congress; and he points to theories regarding Masons and Illuminati. Hofstadter would have recognized the astonishing “reptilian” fantasy, easily explored today on the Web, which holds that the Rothschilds, Rockefellers, Bushes, Windsors, and other dynasties are a race of giant, shape-shifting lizards that have been controlling world politics for millennia.

Both Rich and Berlet have invoked Hofstadter in describing the new rightwing populists as paranoid—some of them only mildly, others to the point of terrifying derangement. Conspiracy theories proliferating today can lend credence to that view. “Birthers” doubt President Obama’s citizenship; “9/11 truthers” accuse the U.S. government of involvement in the terrorist attacks of 2001. Recent acts of awful public violence—flying a plane into an Austin, Texas building where IRS employees worked; attacks inspired by white-supremacist ideology; the murder of the doctor and reproductive-rights advocate George Tiller; etc.—can give the paranoia diagnosis a frightening objective correlative.

Yet much liberal commentary blurs distinctions between those who might be dangerously paranoid and those who strongly disagree with liberal commentary. There is a long and largely unacknowledged history of political violence on both the left and the right (in his suicide note, the Austin kamikaze quoted, perhaps approvingly, from The Communist Manifesto). Rich, one of the few commentators who has pointed to that history, depicts a streak of American madness that reaches extremes of anarchy. But why should we view every futile act of violence as a symptom of mass insanity? The perpetrator might just be doing something wrong. And some judicious liberals might tend to excuse, or at least condemn less harshly, earlier episodes of violence in our history like the abolitionist John Brown’s Pottawatomie massacre, or grotesque killings by Nat Turner’s slave rebels, given the enormity to which those acts responded.

Regardless of whether those acts can be justified, matters so painful and disturbing deserve careful consideration. When Berlet and Rich detail the recent violence, however, they do not raise questions or bring perspective, but generate alarm. “Paranoia” has thus become a conspiracy theory of its own, describing an incommensurable madness “out there” (in Rich’s words, recalling Bryan’s prairie), which Berlet, also with Bryan-like overtones, calls “a perfect storm of mobilized resentment that threatens to rain bigotry and violence across the United States.” Rich’s talk of “mass hysteria, some of it encompassing armed militias, [running] amok,” provides the kind of mystification and horror that Hofstadter said the paranoid style thrives on. When liberal language can be as paranoid as the right-wing kind, paranoia can’t fully explain populism’s right-wing allegiance.

“Why don’t they just vote their interest?” Liberals keep failing to address that question. But history suggests that American populists’ rejection of liberalism is a matter of principle, not of interest. Liberalism has long defined itself from a position of expertise and wisdom that it justifies as meritocracy, and for which it keeps reflexively congratulating itself. Whether lampooning populist farmers as rank yokels, or giving way to a thrilling panic about coast-to-coast violence, or patronizing millions of people’s supposed misguided tropisms, or even, like Lepore, subjecting right-wing enthusiasms to the reflective, nuanced consideration identical with today’s high-quality journalism, liberal claims to a monopoly on knowledge may be even more undemocratic than conservatives’ policies for distributing wealth upward. In America the deadlock between liberalism and populism may be unbreakable.