Democracy is rule by the people. That’s what democrats celebrate and what democracy’s critics condemn. The critics, around since Plato, have an important argument. The people, they say, are neither sufficiently informed nor sufficiently reflective to rule. And because the people are not fit to rule, they need to be governed by an elite whose members—like Plato’s philosopher-kings—think harder and know better.

The American founders were troubled by this problem and proposed an answer to it. Their solution—defined by James Madison—was to make deliberation a key part of the design of the American democratic republic. The idea was “to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens”—to filter public opinion through representatives who would deliberate about public issues. The Constitutional Convention—and the Senate—embodied what Madison called his strategy of “successive filtration.” Even the Electoral College was supposed to provide a basis for electors to deliberate (state by state) and choose the most qualified candidates.

The rise of political parties—more interested in competing for office than deliberating about policy—interfered with this vision. And in successive waves of debate and redesign, stimulated by the Antifederalists, the Progressives, and, later, the further spread of the mass primary and referendum, we have come increasingly to listen to the unfiltered voices of the mass public (or the voices of political elites cut off from the mass public). But is Madison’s option—a deliberative, democratic process that refines public opinion—really irrelevant to our current circumstances? Might there be ways to make our own politics, policymaking, and public dialogue more deliberative?

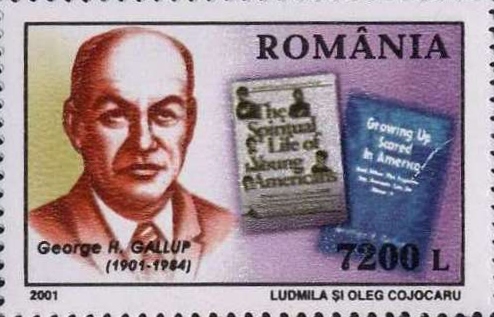

To appreciate the problem and how it might be addressed, consider the role of public-opinion polling, one of the main ways that we have made the public’s unfiltered views consequential in contemporary American democracy. The influential pollster George Gallup co-wrote a book called The Pulse of Democracy, and we use Gallup’s method to take our collective pulse frequently and on every conceivable topic. But these readings often measure little more than the public’s impression of sound bites and headlines. And the manipulation or manufacture of those impressions through focus-group-generated advertising and public-relations campaigns has become a vast enterprise. Our public dialogue has been colonized by a persuasion industry that is more Madison Avenue than Madisonian.

This approach to public opinion represents a sharp departure from Gallup’s original vision, which emphasized the role of opinion polling in the formation of considered opinion. After the initial triumph of the public-opinion poll in the 1936 election (whose results Gallup was able to predict), Gallup outlined these democratic aspirations in a remarkable lecture at Princeton. The poll, Gallup argued, would bring the direct democracy of the New England town meeting to the scale of the nation-state. “The newspapers and the radio conduct the debate on national issues . . . just as the townsfolk did in person in the old town meeting.” And then, through public-opinion polling, “the people, having heard the debate on both sides of every issue, can express their will.” It would be as if “the nation is literally in one great room.”

After seven decades of public-opinion research, we see both the power and the limitations of this vision. The power is that we can take the public’s pulse on almost every conceivable issue on a regular basis. The limitations come from what is being measured. Consider three basic limitations. First, while everyone may, in some sense, be “in one great room,” the room is so big that often no one is listening, and no one is motivated to think much about the issues. In the 1950s, the political economist Anthony Downs coined a term for this problem: “rational ignorance.” If I have but one vote or opinion out of millions, why should I spend a lot of time and effort becoming informed about complex policy questions? My individual vote or opinion will not make much difference. And most of us have more urgent demands on our time and attention. The public’s well-documented low levels of information might be regrettable to democratic theorists, but they are understandable given the incentives facing any individual citizen.

Second, sometimes the “opinions” reported in polls do not exist. Because respondents do not like to say “I don’t know,” they often pick an answer more or less at random. When George Bishop of the University of Cincinnati asked in surveys about the “Public Affairs Act of 1975,” the public offered opinions even though the act was fictional. (And when The Washington Post celebrated the fictional act’s 20th anniversary by proposing its repeal, the public offered opinions about that as well.) Of course, on some issues the public has well-formed opinions, but on many others their opinions may represent nothing more than spontaneous impressions.

A third limitation comes from the way people choose interlocutors and news sources. Even when people discuss politics or policy—and many Americans do—they tend to talk to people like themselves, from similar social spheres and often with similar views. When an intense issue divides the country and you know someone on the other side, you are more likely to discuss the weather than risk potentially unpleasant disagreements. And our expanding choice of news sources, from the Internet to cable, may only contribute to people’s tendency to listen mainly to the like-minded. (See the New Democracy Forum “Is the Internet Bad for Democracy?,” Boston Review, summer 2001.) But whether or not things are getting worse, it is apparent that there is a significant problem. In his classic defense of personal freedom in On Liberty, John Stuart Mill argued that a free society would expose people to diversity, or different “experiments in living,” which would in turn foster “individuality”—Mill’s term for individual self-examination and informed choice among rival ideas and ways of life. That powerful vision of the benefits of freedom is undermined if people exercise their liberty to avoid exposure to diversity.

These three problems with public opinion—rational ignorance, non-attitudes, and the tendency of like-minded people to cluster together—can determine whether polls express the public’s considered judgments about politics or policy. Done well, polls can accurately reflect the state of opinion about a given topic. But whether the responses registered in polls reflect considered judgments depends not on the techniques of polling but on the state of democratic practice. Gallup, among others, showed that informal, unofficial changes in democratic practice can influence the way public opinion shapes our politics. Might there be some way, in a modern context, to combine Madison’s aspiration and Gallup’s?

* * *

The project that I call “Deliberative Polling” represents a promising answer to this question. Whereas conventional polling is a one-stage affair, Deliberative Polling—which we have now tried nearly 50 times—takes place in several steps, starting with a poll of the conventional sort: we have surveyed Danes on the Euro, Texans on utility regulation, national samples of Americans on foreign policy, and a Chinese town on public-works projects. After we complete the survey, we invite respondents to come together for a discussion, typically televised (although we have also recently launched an Internet version that significantly lowers costs). To encourage participation, we provide financial incentives such as travel expenses and an honorarium. Most importantly, we try to convince participants that their voices matter. A national Deliberative Poll will typically gather between 300 and 500 participants for a long weekend in a single place—a large enough sample for the responses to be statistically meaningful, but small enough to be practical. (Because we administer the survey before we invite in-person participants we can compare the attitudes and demographics of the people who come and the people who don’t. We usually find very few statistically significant differences.) The microcosm that gathers for a national Deliberative Poll achieves Gallup’s vision but in a different way than he imagined. It amounts to the nation in one room, but an actual room of manageable size—small enough that participants can reasonably believe that their voices will matter in the process.

Before coming together the respondents are sent briefing materials that outline the major competing policy options and the arguments for and against each. Often developed by advisory committees that represent the key stakeholders, these materials attempt to outline what any informed citizen should know about the current debate on a given issue. Sometimes getting the stakeholders to agree on a balanced, accurate version of the document has required a major deliberative process in itself. Before the national Australian Deliberative Poll on whether the country should become a republic (done in collaboration with Dr. Pam Ryan and Issues Deliberation Australia), the advisory committee, which included the committees for and against the referendum, had to go through 19 drafts.

Once the participants arrive they are randomly assigned to small group discussions with trained moderators who attempt to help the groups work through the issues and also identify key questions that they would like to ask panels of competing experts and policymakers. The weekend alternates small group discussions of approximately 15 people with plenary sessions where all 300 or 400 are gathered together to question the experts and policymakers. At the end of the weekend’s discussions, the respondents take the same questionnaire again. Ideally, a control group—a separate s ample of people who did not participate in the discussions—also take the questionnaire to ensure that changes of opinion really result from the deliberative process and not just from the media or changes in the wider world.

This process—conducted nationally and locally in the United States, Britain, Australia, Canada, Taiwan, Denmark, Bulgaria, Hungary, and, most recently, China—responds to the three basic problems with public opinion as measured in conventional polls. First, the participants are effectively motivated to become more informed, and the motivation seems to make a difference. Consider, for example, a nationally televised Deliberative Poll on U.S. foreign policy in 2003. Before deliberation, just 19 percent of the sample knew (or guessed) that foreign aid was one percent of the U.S. budget or less, a result consistent with other conventional polls. But after deliberation, the percentage answering that foreign aid was o ne percent or less rose to 64 percent. Moreover, this informat ion changed people’s opinions. Before deliberation the majority was for reducing foreign aid. After deliberation the majority was for increasing it.

Sometimes the effects of deliberation are personal as well as political, a point that was brought home for me by a woman who attended the first Deliberative Poll, in 1994, on crime in Britain. She approached me and said she was there accompanying her husband and she wished to thank me. In 30 years of marriage, her husband had never read a newspaper. But since getting invited to this event he had started to read “every newspaper every day,” and he was “going to be much more interesting to live with in retirement.” We had given him a reason to become informed and to overcome rational ignorance. Deliberation can change the habits of a lifetime. When we went back to the sample from the British event some 11 months later, we found that the participants were even more informed than they had been at the end of the weekend. Presumably, they continued to read newspapers and pay attention to the media once activated by the intense discussions of a deliberative weekend.

The second problem with conventional polling is that sometimes the responses to questions do not express real opinions but simply the first thing that comes to a respondent’s mind. This phenomenon was first described by the eminent political scientist Philip Converse. A National Election Studies panel was asked the same set of questions each year from 1956 to 1960. The questions included some low-salience items about such subjects as the government’s role in providing electric power. Converse noticed that some of the respondents offered answers that seemed to vary almost randomly over the course of the panel. They cared so little about the issue that they could not even remember what they had said the previous year in order to try to be consistent. Converse concluded that significant numbers of people were simply answering randomly.

In the Deliberative Poll, ordinary citizens are effectively motivated to consider competing arguments, to get their questions answered, and to come to a considered judgment. Even if they do not have opinions when first contacted, many will form them by the end of the process. In 1996 I was contacted by some electric companies in Texas who faced a new requirement that they consult local residents as part of their planning. Were they going to use coal, natural gas, or renewable energy (wind or solar power)? Would they try to reduce the need for more power through conservation? The companies could not assess public opinion through conventional polls because their customers did not have enough information to have formed real, stable opinions about the issue. But if they consulted focus groups or small discussion groups, they knew that they could never demonstrate to regulators that such small groups were representative. And if they held town meetings, open to everyone, they would get lobbyists and organized interests in the room, not the mass public.

They concluded that Deliberative Polling offered a better solution. We put together a committee of stakeholders representing all the major constituencies to supervise the effort of creating briefing materials, a questionnaire, and an agenda for the weekend. This advisory committee included consumer groups, environmental groups, advocates of alternative energy and more conventional energy sources, and representatives of the large customers. We required events to be public and transparent; the weekend process was televised in the service area, and the public-utility commissioners participated. (These projects were a collaboration with Dennis Thomas, a former chair of the Texas Public Utility Commission; Will Guild, who runs a Texas survey-research firm; and my colleague Robert Luskin.)

The results were striking. In eight Deliberative Polls conducted in various parts of Texas and nearby Louisiana, the public went for shrewd combinations of natural gas, renewable energy, and conservation. The overall percentage of people willing to pay more on their monthly utility bill to support renewable energy went from 52 to 84 percent. The percentage willing to pay more for conservation went from 43 to 73 percent. All the resulting plans included substantial investments in renewable energy—transforming Texas into the second leading state (after California) in wind energy. Undoubtedly, many of the opinions expressed at the end replaced “non-attitudes” (Converse’s term) or phantom opinions. But the point is that the opinions expressed in the end were the considered judgments of representative microcosms: they provided a window on what the public would think under good deliberative conditions.

The third problem that Deliberative Polling attempts to address is that citizens in ordinary life tend to talk to like-minded people and are rarely required to take argu ments from opposing points of view seriously. Our experience in the Danish national Deliberative Poll on the Euro shows the difference between face-to-face discussion at home and in the more balanced setting of a Deliberative Poll. (The project was a collaboration with a team of Danish political scientists led by Kasper M. Hansen and Vibeke Normann Andersen.) Denmark was split more or less down the middle on adopting the Euro. Our questionnaire had information questions, evenly divided between items invoked by supporters of the “yes” side and the “no” side. Between the time respondents were first interviewed and the time they showed up for the weekend, an additional questionnaire was administered. It showed that in preparation for the event, the “yes” supporters tended to learn the “yes” information but not the “no” information. The “no” suppo rters tended to learn the “no” supportin g information but not the “yes” information. “Yes” supporters would know, for example, that Denmark was already engaged in monetary cooperation with other countries, and “no” supporters would know that if Denmark joined the Euro zone then the country could no longer set its own interest rates. Both sides had all the information available to them but learned it selectively. But by the final questionnaire, administered at the end of the weekend, the gap had closed. The “yes” people had learned the “no” information and the “no” people had learned the “yes” information. The Deliberative Poll created a public space where people could reason together, despite their fundamental disagreements on an issue sharply dividing the country.

Sometimes the weight of the other side of the argument is emotive as well as cognitive. In the 1996 National Issues Convention, a televised Deliberative Poll involving presidential candidates and a national random sample, one of the issues was welfare reform and the current state of the American family. An 84-year-old white conservative man happened to be in the same small group as an African-American woman on welfare. At the beginning of the discussions, the conservative said to the woman, “You don’t have a family,” and explained that a family meant both a mother and a father living in the same household with children. The moderator managed to keep the discussion going, and by the end of the weekend the elderly conservative was overheard saying to the woman, “What are the three most important words in the English language? They are ‘I was wrong.’” I interpret that comment to mean that he had come to understand her situation from her point of view—a hallmark of moral discussion. Normally those two would never have had the opportunity for a serious discussion about family, and for the man “women on welfare” would have remained a television sound bite. If we are to understand competing arguments we need to talk to diverse others and understand their concerns and values from their own points of view. Discussions in a safe public space with random samples, randomly assigned, can accomplish that.

* * *

Most recently, the deliberative-polling process has been used to make decisions at the local level in China. Many towns and cities in the rapidly growing portions of China have attempted to consult the public in some way about local policies. But most have held open town meetings in which participation is skewed and organized interests dominate. In April (with the Australian political scientist Baogang He) we completed China’s first Deliberative Poll in Zeguo Township in Wenling City (about 300 km south of Shanghai). A random sample of more than 250 people was asked to deliberate using balanced and accurate information and then to choose the ten infrastructure projects they most preferred from a list of 30. After weighing the merits of various roads, parks, and other proposals, they decided on a list dominated by sewage-treatment plants and a comprehensive environmental plan. The exact priorities of the deliberative microcosm were later ratified by the local People’s Congress and are now being implemented. For local Chinese officials facing a hard budgetary choice among competing projects, the results offered transparency and a way of letting the people decide without resorting to party competition. Further projects are now being planned.

The Chinese experience raises a large question about the political significance of Deliberative Polling in developed democracies: with established systems of representation in place, why should policymakers pay attention to the opinions in a Deliberative Poll? After all, most people do not think seriously about the competing arguments that attach to policy or political issues. Most people have little information and a short attention span. Suppose you are an elected representative. You know that most of your constituents prefer to reduce foreign aid. You also know that they mistakenly believe that foreign aid is one of the biggest items in the U.S. budget. Does it matter to you that if people understood the tiny role of foreign aid in the budget they would wish to increase it?

The elected representatives I have spoken with have consistently told me that it does matter, that they think they should represent the informed opinions of their constituents. And this conviction suggests the currency of a third position in the classic divide between the idea that representatives should follow the wishes of their constituents and the idea that representatives should do what they think is right. The third position is that representatives should do what their constituents would support if their constituents were well informed about the issue. Even Edmund Burke invoked this notion when he claimed, in his classic “Speech to the Electors of Bristol” defending the independent judgment of representatives, that if his constituents only knew what he knew—some 300 miles away in London—then they would agree with him. Hence there seem to be three main roles for the legislator: to represent the wishes of the constituents, to do what one thinks is best, and to represent the hypothetical informed views of constituents. As a retired and influential Congressional lobbyist told me, “Most members would like to do the right thing, if only they can get away with it.” A Deliberative Poll, if it is prominently reported in the media, can give the members cover to do the right thing.

From the standpoint of democratic theory, giving random samples of ordinary citizens the power to make political decisions has some advantages over giving that power to elected representatives. Citizens can deal with issues without worrying about the implications for their re-election. They are not subject to party discipline. They can offer their sincere views at the end of the process without worrying about social pressures from the other participants for consensus. In Madison’s terms, the process of Deliberative Polling does indeed seem to be capable of refining and enlarging public views, of merging the good judgment that comes from deliberation with the citizen involvement that comes with democracy. The result is something like what Gallup hoped for in the conventional poll—a town meeting on a national scale. But getting the informed and representative views of the public requires more than polling alone. It requires an institution that facilitates discussion and grants access to good information and differing experts, and a public space where people feel free to express themselves.