This spring marks the 50th anniversary of Gideon v. Wainwright, in which the Supreme Court considered the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right . . . to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.” The Court unanimously interpreted the Amendment as requiring that states provide attorneys for defendants who lack the resources to hire them privately. The “noble ideal” that “every defendant stands equal before the law,” Justice Hugo Black’s opinion declared, “cannot be realized if the poor man charged with crime has to face his accusers without a lawyer to assist him.” Given an attorney for his retrial, Clarence Gideon was acquitted.

Today, the vast majority of felony defendants depend on appointed counsel to represent them, and the quality of representation varies wildly.

At one end of the spectrum, indigent defendants represented by some public defender organizations receive counsel every bit as expert as the most well-heeled client could buy. But the majority of the states that operate public defender services fail to meet the federal government’s standards for attorneys’ maximum caseloads. And many defendants receive dreadful representation: a shockingly high percentage of defendants sentenced to death were represented by lawyers who were either disciplined or disbarred at some point in their careers, often within a few years of the defendants’ trials. Indeed, there are enough instances of lawyers who literally slept through their clients’ trials to produce a grotesque jurisprudence regarding when somnolence rises—or sinks—to the level of a Sixth Amendment violation.

The Supreme Court has recognized that just-any counsel isn’t good enough. But the Court’s standard for constitutionally ineffective assistance, announced in Strickland v. Washington (1984), makes it extremely hard for a defendant to argue that his lawyer failed him. A defendant challenging his conviction not only has to show that his lawyer’s performance fell below a relatively deferential bar, but also has to prove prejudice—that is, a reasonable probability that, but for the errors, the outcome would have been different. By contrast, for most other constitutional violations, the burden is on the government to show the error was harmless. And although in recent years the Court has been somewhat more vigilant in enforcing the Sixth Amendment—requiring in Padilla v. Kentucky (2010), for instance, that lawyers provide accurate information to noncitizen clients about the immigration consequences of pleading guilty—its promise all too often goes unfulfilled.

Consider two examples that provide powerful illustrations of how Gideon’s trumpet—to borrow from the title of Anthony Lewis’s superb 1964 book about the case—has been muted.

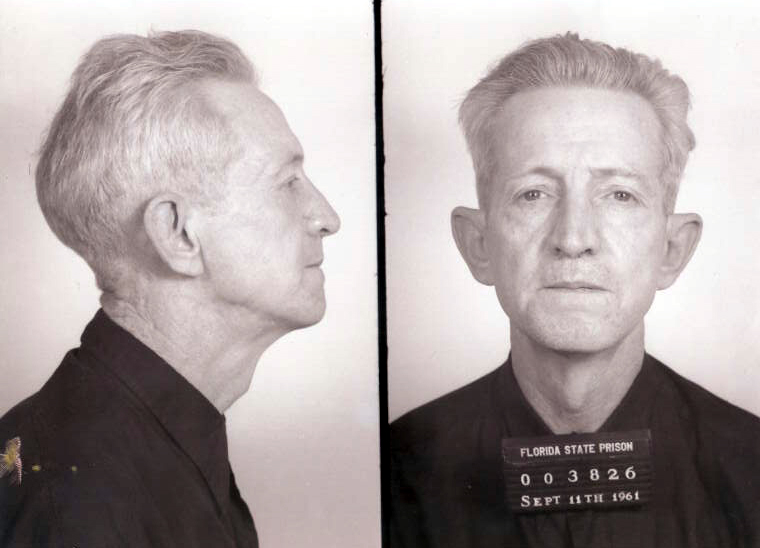

One is Boyer v. Louisiana, a case pending at the Court this term, in which the state charged Jonathan Boyer with capital murder in 2002. Boyer, who has a borderline I.Q., a third-grade reading level, and a history of mental illness, had admitted under police interrogation to killing the victim, but his statement did not match the physical evidence in several relevant respects. There was also at least one other plausible suspect.

Louisiana has a long history of underfunding its indigent defense system, and at the time Boyer was charged, the state provided no resources to indigent defense. Local indigent defender boards were funded essentially by revenue from traffic tickets, which fluctuated dramatically from year to year.

In Boyer’s case, the public defender was unavailable due to a conflict of interest. So the judge drafted a practitioner from a small firm to represent Boyer. But there were no funds available to compensate the lawyer for the hundreds of hours he would be required to devote to the case or for out-of-pocket litigation expenses. The next five years were consumed by proceedings trying to obtain those funds. Those proceedings were repeatedly postponed to await decisions in parallel cases also involving unfunded indigent defense.

When Boyer’s attorney moved to dismiss the charges against his client for violation of a different provision of the Sixth Amendment—the right to a speedy trial—he was forced to abandon that claim because, in a Kafkaesque twist, the very lack of funds that had caused the delay had also prevented him from showing why the delay had impaired his ability to mount an effective defense.

A high percentage of defendants sentenced to death were represented by lawyers who have been disciplined or disbarred.

In the end, the state abandoned the capital charge against Boyer so that it could proceed against him on a lesser charge for which he could be represented by a less experienced attorney. By the time of the trial, a number of potentially relevant witnesses had either died or gone missing. Boyer was convicted by a non-unanimous jury (a practice permitted only in Louisiana and Oregon) and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

On appeal, the state appellate court recognized that the extraordinary delay in bringing Boyer to trial raised a red flag under the Supreme Court’s foundational speedy trial case, Barker v. Wingo (1972). But in another twist, it held that the “funding crisis” was a “cause beyond the control of the state,” and therefore the prosecution had proceeded properly.

The narrow issue before the Supreme Court this term is whether Louisiana’s failure to provide any funding for defense counsel for five years should be weighed against the state for speedy trial purposes. But lurking beneath that issue is the far broader point that Louisiana’s system, even after recent reforms, fails to deliver on the promise of Gideon.

Another example of the Sixth Amendment’s false promise arises from more mundane sources than Boyer’s murder charge: misdemeanor cases. A decade after Gideon, in Argersinger v. Hamlin (1972), the Court extended Gideon, which applied only to felony cases, to all criminal prosecutions, including misdemeanors, in which jail time is imposed. The government can prosecute misdemeanors without providing counsel to indigent defendants, but unless the defendant waives his right to counsel, the judge cannot order the defendant to serve time if he is convicted.

And yet, as a practical matter, misdemeanor defendants may face a cruel dilemma. A 2009 investigative series in the San Jose Mercury News discovered that in Santa Clara County, California, defendants charged with misdemeanors were not provided attorneys at arraignment—generally their first court appearance. Instead, they faced the option of asking for a lawyer, in which case they might be kept in custody until one is appointed, or of pleading guilty on the spot. Without a lawyer at arraignment, many defendants will find it difficult to get pretrial release, as work by legal scholar Douglas Colbert has shown.

The upshot is that unrepresented defendants often end up getting the equivalent of a jail sentence, only they serve it before they’ve been convicted.

And in many cases, they might never be convicted if they receive competent counsel. A Mercury News study of roughly 250 defendants charged with resisting arrest found that while almost half of the represented defendants had their charges reduced or dropped altogether, only one in ten self-represented defendants did. Moreover, defendants who plead guilty simply to avoid being locked up while they wait for a lawyer to be appointed will be stuck with criminal records and all the consequences they entail.

Underfunding misdemeanor defense creates its own problems. In Detroit, according to a 2008 National Legal Aid & Defender Association report, lawyers spend around half an hour, on average, on each misdemeanor case.

Misdemeanor cases may not be as striking as Jonathan Boyer’s, but they too illustrate the significant costs inflicted by the failure to honor Gideon. As Justice Black put it 50 years ago, “Lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries.”