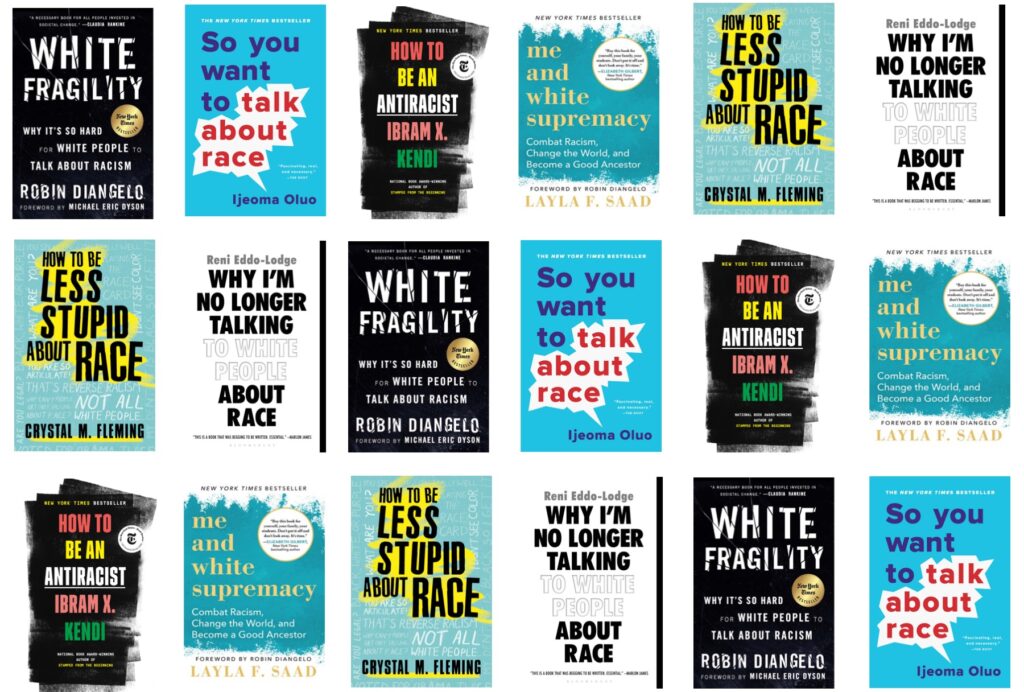

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism

Robin DiAngelo

Beacon Press, $24.95 (cloth)

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race

Reni Eddo-Lodge

Bloomsbury, $27 (cloth)

How to Be Less Stupid About Race: On Racism, White Supremacy, and the Racial Divide

Crystal M. Fleming

Beacon Press, $23.95 (cloth)

How to Be an Antiracist

Ibram X. Kendi

Random House, $27 (cloth)

So You Want to Talk About Race

Ijeoma Oluo

Seal Press, $27 (cloth)

Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor

Layla F. Saad

Sourcebooks, $25.99 (cloth)

There is a long tradition of white people thinking they can read their way out of trouble. Examples abound, from sentimental novels like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)—which engaged white antebellum readers through appeals to sympathy and Christian sentiment—to sociological readings of race novels by mid-twentieth-century middlebrow book clubs, the formation of “U.S. ethnic lit” during the canon wars of the 1980s and ’90s, and the explosion of “global literature” in recent decades. As Jodi Melamed noted almost ten years ago in Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism (2011), “The idea that literature has something to do with antiracism and being a good person has entered into the self-care of elites, who have learned to see themselves as part of a multinational group of enlightened multicultural global citizens.”

Antiracist reading lists are proliferating like weeds in the wake of the 2020 uprisings, sending antiracism books to the tops of the best-seller charts.

It comes as little surprise, then, that antiracist reading lists are proliferating like weeds in the wake of the 2020 uprisings, sending antiracism books to the tops of the best-seller charts. This is the literature of white liberalism. Promised on the other end of this genre is a self-reflective, emotionally regulated white (or white-adjacent) antiracist person who can be incorporated into U.S. political modernity (one that will be majority-minority by 2045). In the literature of white liberalism, those who cannot embrace this demographic truth condemn themselves as backward, redneck racists who don’t read books—and who are dying of whiteness.

This genre hails a multiracial, though white-majority, class formation—not the 1 percent, but the top 20 percent, the upper-middle class dream hoarders. Now that this moment is publicly laying bare the pitiful inroads made by “diversity and inclusion” (according to Crystal Fleming, the institutional complement to “thoughts and prayers”), the top 20 percent must admit that it needs to transform itself in some small way in order to save itself—an example of Derrick Bell’s theory of “interest convergence.” However, unlike previous moments in which fiction supposedly becomes the portal to empathy for the Other, the contemporary literature of white liberalism eschews the novel and coheres around the genres of nonfiction, autobiography, and self-help. The most widely popular fictional media of the current moment—scripted film and television—renders white liberals as generous white saviors (The Help, the fourth most popular movie on Netflix on June 9, 2020), or as laughably irredeemable (Get Out and the many memes that have referenced it to critique the Democratic party’s obscene donning of kente cloth).

The literature of white liberalism has emerged as a distinct post-Coatesian genre of nonfiction intended to share vocabulary with those who are entering “race talk” for the first time. If Ta-Nehisi Coates’s wildly successful “The Case for Reparations” (2014) and Between the World and Me (2015) helped millions of white and white-adjacent liberals see that anti-Black racism was a problem, the election of Donald Trump underscored that it was their problem. These books, all published pre-pandemic and pre-uprising, were made possible by the failures of “post-race” discourse, the diversity, equity, and inclusion industrial complex, public receptivity to the Black Lives Matter movement, the re-emergence of popular feminisms, and alarm over growing white nationalist movements.

During the Great Awokening of 2020, precipitated by the uprisings following the concurrent May 25, 2020, murder of George Floyd and the Amy Cooper Central Park incident, the media tide turned from handwringing about euphemistic “race relations” to focus on what Eduardo Bonilla-Silva has deftly termed “racism without racists” and what Mica Pollock has described as colormuteness—the inability or refusal to talk about race and racism. The literature of white liberalism attempts to address this status quo. Of the books examined here, two present themselves as “how-tos,” two use “talking” in their titles, and four explicitly name whiteness.

This contemporary iteration of the literature of white liberalism is provocative in that several of its books pivot from “racial literacy” to emotional literacy. In doing so, they attempt to help colormute readers see, hear, think, and respond to the concepts of race and racism without triggering the sympathetic nervous system—without launching into fight-or-flight mode, which too often materializes as denial, anger, silence, or white women’s tears. Such reactions are spawned by the reliance of the culture of white supremacy on niceness, toxic masculinity, individualism, and an avoidance of open conflict.

Whether white people’s racial or emotional literacy can meaningfully contribute to abolitionist projects or Black freedom struggles is a long-contested story, particularly in the U.S. left. In its class-first and class-only zeal, the New Left purposefully expelled Black feminist and women of color epistemologies from left politics in the latter half of the twentieth century and thus bequeathed a disdain for and ignorance of Black feminism that the millennial and zoomer left must now scramble to resolve. Indeed, what is particularly interesting about the furor over the literature of white liberalism is how many—and which—white people think they are already too woke for its lessons.

The true import of the literature of white liberalism, then, is not the impact it has on white liberals—who are at the twilight of their power—but its impact on nominally multiracial yet white-majority left formations. For decades these formations have rejected radical Black and minoritized thought in favor of white-centered class reductionism, regarding BIPOC as elements to be “included” into a multicultural fold rather than as a transformational intellectual force. How will the left’s historical negation of minority thought be accounted for in a moment when the work of Black feminist abolition is driving the nation’s largest uprisings in fifty years?

The literature of white liberalism generally falls into two categories, depending on whether it draws material from white people’s feelings and experiences or Black people’s. Books in the latter category, though varying in degrees of self-disclosure, typically take the form of an autobiographical bildungsroman of racial literacy, narrativizing the authors’ journeys to and through Black racial consciousness in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. By contrast, the books that center whiteness encourage white people to name white supremacy, to reflect upon and eventually create their own narratives of racial literacy. (Biracial, multiracial, and non-Black people of color tend to be waved away with a cursory mention of the complexity of their subjectivities, leaving ample room for additional authors to elaborate in these areas.)

Kendi’s main point—one echoed by all of these books—is that it is not sufficient to be “not racist”: we must be actively antiracist.

Both Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist and Crystal M. Fleming’s How to Be Less Stupid About Race announce themselves as how-to books, though they aren’t exactly. Both are memoirs of their authors’ journeys to antiracism, not guides for a general white audience. Kendi and Fleming are both professors—Kendi just left the School of International Service at American University for Boston University’s Center for Antiracist Research, and Fleming is Professor of Sociology at Stony Brook University—so it makes sense that both books chronicle their authors’ own racial miseducation and intellectual biographies. Both authors emphasize that they weren’t born knowing all about race and racism, positing antiracism as a lifelong journey.

How to Be an Antiracist opens with a memory of shame. The teenaged Kendi, a student at Stonewall Jackson High School, delivers a speech at the Martin Luther King, Jr., oratorical contest excoriating his fellow Black youth for the usual ills of not pursuing education, of too many teen pregnancies, and of overvaluing sports and music. Years later he realizes that “racist ideas fooled me nearly my whole life.” Situating his upbringing as part of the Black middle class in the Reagan era, Kendi recounts how he absorbed and parroted anti-Black attitudes for years. After pivoting to become a reactionary “anti-White racist” in college, he finally settled upon a mature antiracism as he grew through encounters with other Black intellectuals, particularly Black queer feminist thinkers, in graduate school. Kendi’s autobiographical journey through racial consciousness and antiracist consciousness is interspersed with history, personal commentary, and reviews of policy and statistics. His main point—one echoed by all of these books—is that it is not sufficient to be “not racist”: we must be actively antiracist. (This claim is also popularly attributed to Angela Davis, but without definitive citation.)

Because Kendi opts instead for a strict racist/antiracist binary, his threshold for who is “racist” is fairly low: anyone not actively antiracist is racist. This makes most people—the teenaged Kendi and other BIPOC included—racist. Kendi’s purposeful lack of nuance with language can be distracting, especially around gender and sexuality, and many of the clumsy terms he coins to acknowledge intersectionality are unlikely to win popular usage. In one example, he explains, “Homosexuals are a sexuality. Latinx people are a race. Latinx homosexuals are a race-sexuality.” He operates similarly with gender: “When we identify Black women, we are identifying a race-gender.” But, as with antiracism, Kendi understands Black queer feminism as a positivist commitment to action, instead of merely being “not patriarchal.”

Of all the books in this review, Kendi’s decenters whiteness the most; this is his autobiography and his intellectual bildungsroman, written during a frightening bout of colon cancer. He also claims he isn’t interested in suasion, in changing hearts and minds. Instead, he argues, we should “focus on changing policy instead of groups of people.” This seems somewhat contradictory, given Kendi’s own story of evolution through self-reflection and challenging interactions with others, but his point is that the “journey” from racist to antiracist should not fall upon individuals. Instead, it can be avoided by administering antiracist policies.

Like Kendi’s book, Fleming’s How to Be Less Stupid About Race: On Racism, White Supremacy, and the Racial Divide opens with an excoriation of what she terms “racial stupidity” by focusing on herself. “I was one of those black kids who didn’t know they were black,” she admits, citing her upbringing in a sheltered Pentecostal community. Selected for the talented and gifted track at school, she built her self-worth around her academic achievement. Ensconced in the power-blind logic of exceptionalism, Fleming confesses she was “this close to becoming some version of Ben Carson, Kanye West, or Omarosa.” A turning point came when she chanced upon Introduction to Sociology in college. The book’s seven chapters follow Fleming from racial stupidity through racial literacy while also serving as a layperson’s guide to critical race theory, intersectionality, DNC hypocrisy, news media complicity, white supremacy, interracial versus antiracist love, and antiracist praxis.

Calling Black life writing a “how to” for white readers joins a tradition that makes information retrieval the sole function for non-Black audiences.

Fleming’s goading usage of the term “racial stupidity” challenges assumptions of white intelligence about race matters and expands on Charles Mills’s assertion that “the maintenance of white supremacy involves and requires ‘cognitive dysfunctions’ and warped representations of the social world,” stabilized by white-dominant institutions such as the media and formal education. Observing race-talk in the public sphere, Fleming argues that “the main lesson most whites absorbed from the civil rights era wasn’t that they have a personal responsibility to fight systemic racism but, rather, that they have a responsibility to maintain a public appearance of being ‘nonracist’ even as racism pervades their lives.” White people thus focus not on the trouble of racism itself, but on the potential of “a failed public performance of being nonracist.” This distinguishes the work of the ally, whose identity depends upon the public performance of being nonracist, from the radical work of the accomplice, who exploits a lack of visibility.

In her last chapter, Fleming delivers the “how to” promised in the title. How does one become less stupid about race? By developing racial literacy through increased awareness and insight, forming new relationships, and organizing. Though Fleming lists ten concrete actions—such as “amplify the voices of black women, Indigenous women, and women of color,” “shift resources to marginalized people,” and “disrupt racist practices”—this might not satisfy those who wish for a grander structuralist solution. Fleming insists that antiracist work must have an individual component: “the answer is going to vary for each individual, depending on your personality and background, interests, talents, and inclinations.” There is no one-size-fits-all panacea; rather, to paraphrase Marx, it is from each according to her ability. Antiracism needs to start as an assessment from within, both Fleming and Kendi suggest.

Yet this emphasis on antiracism as a personal journey—and the antiracist as a particular type of person—recently led writer and scholar Lauren Michele Jackson to regard antiracism as “something of a vanity project, where the goal is no longer to learn more about race, power, and capital, but to spring closer to the enlightened order of the antiracist.” Ultimately, How To Be an Antiracist and How To Be Less Stupid About Race attempt to position antiracism as an orientation toward knowledge and action rather than self-image, but calling Black life writing a “how to” for white readers is in the end misleading, joining a tradition that makes information retrieval the sole function of Black art and thought for non-Black audiences.

Whereas scholars Kendi and Fleming offer how-tos via life writing, Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race and Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race are by journalists who focus on “talking about race.” As a writer active on social media, Oluo testifies that this is a real need. “People find me on online messaging platforms and beg me not to make their questions public,” she reports. “People create whole new email accounts so they can email me anonymously.” Oluo’s book is targeted at people who want to develop racial literacy without putting their feet in their mouths, recalling Fleming’s observation that “good” white people strive to publicly appear nonracist.

Historically, neither center-left nor further-left white-majority movements have much enjoyed discussing white fragility.

In its seventeen chapters So You Want to Talk About Race raises and addresses questions such as: “What if I talk about race wrong?” “What is cultural appropriation?” and “I just got called racist, what do I do now?” Oluo answers in a relaxed style, as a friend might. Her goal is to help the reader see situations through her perspective as a Black woman. Each chapter begins with a personal story about how the topic plays out in Oluo’s life (people asking to touch her hair; the school-to-prison pipeline; affirmative action), moves to the topic’s larger history or context, and closes with counter-arguments, questions, or bullet points for the reader to deliberate on. Her “user-friendly” style is purposely undercut in the last chapter, “Talking is great, but what else can I do?” Here, Oluo tempers the attention to conversation by recounting her experiences with white people’s addiction to talk. She notes, “While many people are afraid to talk about race, just as many use talk to hide from what they really fear: action.”

Like Fleming, Oluo ends by giving her readers a plethora of suggested actions. (Whether or not the reader acts is out of the author’s hands.) Oluo is an engaging storyteller, and in asking for empathy for her own perspective, she generously—perhaps too generously—offers it back to the reader. On police brutality, she writes, “I know that it’s hard to believe that the people you look to for safety and security are the same people who are causing us so much harm. But I’m not lying and I’m not delusional. I am scared and I am hurting and we are dying. And I really, really need you to believe me.”

Such pleading takes an immense toll on Black people, as detailed by Eddo-Lodge, who writes from the United Kingdom. Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race has its origins in a 2014 blog post of the same name, in which Eddo-Lodge detailed her new boundaries:

I can no longer engage with the gulf of an emotional disconnect that white people display when a person of color articulates their experience. . . . Their throats open up as they try to interrupt, itching to talk over you but not really listen, because they need to let you know that you’ve got it wrong. . . . I’m no longer dealing with people who don’t want to hear it, wish to ridicule it and, frankly, don’t deserve it.

Eddo-Lodge’s refusal paradoxically opened up more doors for her to talk about racism in the UK, where she spent the following five years on the lecture circuit at festivals, schools, political spaces, and in the media. Earlier in June, her book reached number one on the UK non-fiction chart, the first by a Black British author—a success she celebrated with a grain of salt.

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race begins with a quick rundown of Black British history, then discusses structural racism, white privilege, anti-immigrant Brexit sentiment, white feminism, and white Marxism. It, too, concludes with a call to action. However, whereas Oluo is up for a friendly conversation, Eddo-Lodge takes a no-nonsense approach, covering her topics with biting verve. On structural racism she remarks, “You’d have to be fooling yourself if you really think that the homogeneous glut of middle-aged white men currently clogging the upper echelons of most professions got there purely through talent alone.” As a writer, speaker, and media commentator, Eddo-Lodge is well positioned to observe how the British mainstream media elevates white supremacist views while silencing others. She advocates for robust debate in the public sphere and calls for mainstream media outlets to publish radical commentary with the same force that it publishes right-wing writing—not, she writes, “the kind of wishy-washy liberalism that harps on about the cultural and economic contributions of migrants to this country as though they are resources to be sucked dry.”

Eddo-Lodge also recounts an incident during her appearance on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour, when she was asked why intersectionality produced violent bullying against white feminists. She reports that gaslighting of this sort appears in leftist outlets, too. For example, the New Statesman suggested that the framework of intersectionality was classist because of the term’s circulation in academia, conveniently conflating the actual phenomenon with the term itself. The New Statesman’s frequent screeds against intersectionality led Eddo-Lodge to conclude there was an editorial line against it. While Gen Xers Kendi and Fleming call out the ineffectiveness of the Democratic Party, millennials Oluo and Eddo-Lodge identify the white fragility that permeates white-centered left spaces as impediments to social justice. Eddo-Lodge, for example, defines identity politics as “a term now used by the powerful to describe the resistance of the structurally disadvantaged.”

For Oluo, intersectionality bothers white-majority left formations because it “decentralizes people who are used to being the primary focus” and “forces people to interact with, listen to, and consider people they don’t usually interact with, listen to, or consider.” These movements center the (white) majority—because minoritarian needs are “divisive”—and leads them to practice “trickle-down social justice.” Oluo’s first chapter—“Is it really about race?”—opens with her weariness at having still another “class versus race” conversation with a white male leftist. Historically, neither center-left nor further-left white-majority movements have much enjoyed discussing white fragility, instead regarding such self-reflection as an obsession with feelings, relationships, and moral purity. In their resistance to understanding difference as a legitimate mode of knowledge production rather than as a category of identity, both liberals and leftists have advocated neoliberal multiculturalist understandings of diversity and inclusion (“our editor is brown” or “I have a BIPOC friend/comrade,” etc.) as substitutions for actually allowing their respective philosophies to be transformed by minoritized, feminized, and queered methods of knowing and being.

Overall, the efforts of Kendi, Fleming, Oluo, and Eddo-Lodge accept that white and non-Black audiences may lack an understanding of Black perspectives—despite the fact that Black people have been publicly creating and organizing around freedom struggles for centuries. We should credit the optimism and critical generosity these authors generate through the act of writing and publishing. But is white supremacy really a problem of knowledge? The literature of white liberalism that centers white perspectives—Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism and Layla F. Saad’s workbook Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor, which includes a foreword by DiAngelo—takes as its central quandary that white supremacy allows white people to know, sense, and feel very little about themselves as racialized subjects.

We should credit the optimism and critical generosity these authors generate through the act of writing and publishing. But is white supremacy really a problem of knowledge?

For this reason, DiAngelo’s White Fragility has been the most galvanizing book of the literature of white liberalism. Introduced in article form in 2011 and expanded as a book in 2018, the thesis of white fragility circulated in progressive racial justice activist and educational circles for several years without major crisis. It was not until the white media class got whiff of the book during the 2020 uprisings that a strong public backlash began to form. This led sociologist Dr. Jenn Sims to remark on Twitter, “Some of yall with big opinions on what newly aware white folks should read first to learn abt structural racism have never taught Intro level race classes to hundreds of racially illiterate white students AND IT SHOWS.” Indeed, many pundits have been enraged by the suggestion that some white people might need psychological and emotional preparation to learn about structural racism. (Some BIPOC writers have professed this opinion, as well—a reminder that white liberalism is a multiracial formation.)

According to DiAngelo, one factor (not the sole factor) delimiting racial justice is white people’s low threshold for racial stress and the damage this causes to BIPOC and social justice movements. This is white fragility: “A state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress . . . becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves.” Race-based stress in white people can be triggered by the proposition that “being white has meaning,” witnessing “challenges to white power and control,” and being challenged on the conviction that because they are a “good person,” they cannot possibly be racist. DiAngelo identifies common response patterns, including “the outward display of emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt and behaviors such as argumentation, silence, and leaving the stress-inducing situation.” The notion of white fragility replaces idle “check your privilege” declarations and engages the insights of the psychology of cognition and emotion. DiAngelo denaturalizes white people’s reactions, understanding them not simply as “individual opinion[s]” but an observable pattern of social psychology.

While DiAngelo recognizes the therapeutic orthodoxy that there are no bad emotions—anger, fear, guilt, and avoidance may indeed be authentic expressions of white racial stress—she contends that white fragility still destroys social environments. White Fragility doesn’t negate structural racism; rather, it offers a different elaboration of it. The book argues that structural forms of oppression manifest through interpersonal interactions as white people emotionally manipulate, bully, or gaslight BIPOC when challenged on race matters. (This led writer Shelagh Brown to reclaim white fragility more accurately as white hostility.) Imagining the perspective of a white person expressing this fragility, DiAngelo writes: “I am going to make it so miserable for you to confront me . . . that you will simply back off, give up, and never raise the issue again.” This thinking means that “white fragility keeps people of color in line and ‘in their place.’ In this way, it is a powerful form of white racial control.” The concept of “white fragility” is a useful companion to Audre Lorde’s “The Uses of Anger,” naming the attitudes identified by Lorde in her 1981 speech: “I speak out of direct and particular anger at an academic conference, and a white woman says, ‘Tell me how you feel but don’t say it too harshly or I cannot hear you.’ But is it my manner that keeps her from hearing, or the threat of a message that her life may change?” Citing Lorde’s speech, DiAngelo affirms that emotions are political, and that progressive white people need to learn to regulate their emotions around race-talk if they want to cease harming BIPOC. In this way, White Fragility is very much an analysis of power.

White Fragility doesn’t negate structural racism; rather, it offers a different elaboration of it.

White Fragility is addressed to white progressives because, as DiAngelo emphasizes, “white progressives cause the most daily damage to people of color.” White progressives expend more energy “making sure that others see [them] as having arrived” than engaging in the daily work of self-reflection, continuing education, coalition building, and antiracist praxis. She argues that white supremacists are “more aware of, and honest about, their biases” than white progressives. This view echoes Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s not-famous-enough passage from “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” about his disappointment with the waffling white moderate, in contrast to the obvious hatred of the white supremacist. This fear of being on the wrong side of the good white person/bad white person binary speaks to the cardinal rule of white fragility: “Do not give me feedback on my racism under any circumstances.”

DiAngelo’s concluding chapter—“Where Do We Go From Here?”—does not suggest launching into action as do the other books in this review. Instead, it asks readers to pause, slow down, and learn to recognize and manage their emotions before causing more harm. It does not advocate for perfection or purity before action; it champions praxis. It teaches white people how to apologize to a coworker (perhaps the sole BIPOC in many white people’s lives), find steps toward genuine repair, and learn emotional intelligence and resilience in the context of race talk.

This seems like a low bar, yet it has made many people on Twitter irredeemably angry. But if white people committed to taking feedback on their racism—and men on their sexism, cis people on their transphobia, straight people on their homophobia, abled-bodied people on their ableism, elites on their classism—what else might be accomplished within social movements? How might movements expand if they saw the disappearance of oblivious and unaccountable types, such as the mansplaining feminist, the self-centering white ally, or, as Oluo put it, “every other white dude in my political science class?” White Fragility is radical because most people—white or not—don’t know how to apologize and repair anything, let alone a racist interaction. Again, the book doesn’t pretend that improved interpersonal exchanges will abolish racial capitalism writ large; it unambiguously tells white people that their lack of emotional self-regulation around racism is exhausting for BIPOC, gets in the way of BIPOC’s everyday flourishing, and forestalls meaningful social change of any kind. It does not suggest that the answer is to be nice and keep smiling, but rather to break white solidarity. Whether DiAngelo’s millions of new readers will have the same takeaway remains to be seen.

White Fragility has been critiqued from the left for a variety of reasons, including DiAngelo’s work as a corporate diversity consultant. That hardly disproves the existence and problem of white fragility, though, and it is disconcerting how many responses to the book focus on DiAngelo’s circulation in the professional-managerial class as a substitute for talking about white fragility, white supremacy, or antiracism in their authors’ own communities. Let’s ask, for example, who is bearing the unrecognized load of antiracist education in white-majority political groups, social scenes, or affinity circles (answer: women and femmes, likely of color). Let’s also consider the consequences of a colormute left that exempts itself from white fragility: it only attracts those people of color who are willing and able to put up with white shenanigans. A left, even a multiracial one, that tolerates white fragility and toxic masculinity is engaged in the project of building a world that is far too similar to the one we’re in now. Yet a disheartening number of young leftists believe that liberal antiracism—the kind that can be subsumed into workplace trainings—is the horizon of antiracist possibility. Black radical feminism has always been forging new futures into being, but its total omission from, say, discussions of Mark Fisher’s immensely popular 2009 book Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? is telling of the extreme myopia of white-majority left formations.

DiAngelo has also been critiqued for a being a white woman. Those who don’t want to engage the idea of white fragility with anyone except a Black author can certainly refer to texts by any of the Black women mentioned here: Lorde, Fleming, Oluo, and Eddo-Lodge. Yet many on the left exempt themselves from white fragility, preferring to believe that a critique of the diversity, inclusion, and equity industrial complex—with maybe a mention of Claudia Jones, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, or the Combahee River Collective Statement from 1977—is sufficient antiracist work for a revolutionary transformation of society. Actually, it is barely the beginning.

Meanwhile, elite “freethinking” critics have offered variations on #NotAllWhitePeople that evacuate white supremacy’s power dynamics from the conversation. “She’s got about 25 proscriptions that make it so that any good white person is essentially muzzled. You just have to be quiet,” said John McWhorter in an interview on Morning Edition. Equating a list of suggestions in a book with being “essentially muzzled” is a free-speech dog whistle. And just who or what is a “good white person”? As DiAngelo proposes, the good white person/bad white person binary is ineffectual; people must see themselves as participants in a society structured in anti-Blackness, but McWhorter does not live in this society. In an Atlantic essay, he charges that asking non-Black people to take into account Black people’s feelings when talking about race is condescending to Black people. But his reasoning for why this consideration is unwarranted is that he personally benefitted from affirmative action: “In my life, racism has affected me now and then at the margins, in very occasional social ways, but has had no effect on my access to societal resources; if anything, it has made them more available to me than they would have been otherwise.”

Other critics in liberal outlets have also doubted this world supposedly structured by anti-Blackness. In the Washington Post, Carlos Lozada writes skeptically of DiAngelo’s suggestion that white people are “socialized to ‘fundamentally hate blackness’ and to institutionalize that prejudice in politics and culture.” Lozada also complains that white fragility employs a circular logic (an assertion also lobbed at feminism): attempts to deny white fragility are taken as evidence of white fragility. It is unlikely that any reader will agree that white fragility exists if they do not agree with DiAngelo’s premise that racism is structural and not merely a set of individual actions.

White Fragility has also been critiqued for elaborating white feelings instead of a materialist analysis of racism, but this ignores how white feelings structure the everyday realities of BIPOC in ways that engender material consequences, such as the toxic bodily tolls of allostatic load and minority stress. Moreover, it assumes that cultivating emotional awareness and relational skills is unimportant, or even contrary, to radical praxis (or even basic human existence). Relationality and interdependence have not been front and center for masculinist leftist formations, which have instead preferred to keep their theorizing of relationality limited to the word “solidarity.” By contrast, radical relationality has long been central to various forms of anti-capitalist feminist, queer, trans, women of color, and abolitionist organizing, not to mention foundational to Indigenous intelligence. The Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective, for example, held an Apology Lab that would likely draw ridicule from right- and left-wing commentators alike. But who benefits when relationality is left off the table? And who is uplifted and healed when relationality is centered? The uproar over White Fragility functions as an indirect introduction to such questions.

The latest of the books under review here, Layla F. Saad’s Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor, aims solely to aid the reader in praxis. It begins with the presumption that white supremacy is partially defined by epistemicide—the erasure or suppression of knowledge formations. The foreword (by DiAngelo) suggests that for the newly arrived, the first question is not “What do I do?!” (because, invariably, they will do the wrong thing or get in the way) but “How have I managed not to know?” The practice of epistemic de-linking is sensible, but it also exemplifies what Saidiya Hartman recently noted as “a translation of Black suffering into white pedagogy.” This occurs when a spectacular episode of anti-Black violence produces white surprise, and calls for education about circumstances white people have already been deeply entrenched in.

Saad is generously willing to give white people the benefit of a doubt. A contemporary manifestation of feminist consciousness-raising (CR), Me and White Supremacy is a workbook, not an autobiography, consisting of a four-week curriculum based on twenty-eight daily journal prompts on white supremacy. Many of Saad’s prompts recall those included in Tia Cross, Freada Klein, Barbara Smith, and Beverly Smith’s “Face-to-Face, Day-to-Day, Racism CR” (1980), which asked participants to recall memories around race and racial difference from early childhood, adolescence, and their journeys as feminists. One of Saad’s prompts asks, “What types of situations elicit the most white silence from you?” Another inquires, “What is the first instinctual feeling that comes up when you hear the words white people or when you have to say Black people?” Another asks for evidence: “If you are someone who has called yourself an intersectional feminist, in what ways have you been centering BIWOC?” While second-wavers used CR sessions to strengthen communities in order to facilitate further action, it remains to be seen whether Saad’s book can provide a similar springboard. Hers is the only book under review that explicitly imagines this work done collectively, even as the literature of white liberalism is adopted by book clubs, churches, and antiracist groups. Saad encourages enlisting an accountability partner for support, and also gives careful instructions for completing the workbook in groups using a facilitation method called The Circle Way.

Saad is adamant that the book really is a workbook that must be engaged with, not just read. To those discomfited by the confessional nature of the prompts, she writes: “White exceptionalism is the little voice that convinces you that you can read this book but you do not have to do the work. . . . [It] is the belief that because you have read antiracism books and articles . . . you know it all and do not need to dig deeper.” Throughout, Saad uses several metaphors—surface and depth, holding and purging, evil and light—to think about white supremacy as an internalized and embodied experience:

White supremacy is an evil. . . . it is living inside you as unconscious thoughts and beliefs. The process of examining it and dismantling it will necessarily be painful. It will feel like waking up to a virus that has been living inside you all these years that you never knew was there.

The workbook—when done correctly—thus promises a kind of exorcism: a painful process of purging and a re-introduction to feeling. Because some antiracist work like Saad’s draws from Abrahamic forms of moral adjudication such as confession and exorcism, or because it is initiated in the sphere of language (à la the psychotherapeutic “talking cure”), some critics have characterized social justice discourse as embarrassingly penitential, overly confessional, cultish, pathologically feminine, narcissistic, bourgeois, ineffectual, and so forth. Saad’s work insists that confronting one’s own racism is not about exorcising it from the body onto the page or into a monologue, but moving one’s shame and fear around race-talk away from its violent projection onto the body of the Other (i.e., “angry Black women”) and recognizing it within oneself.

This approach is relational rather than individualist. For Saad, the purpose of the work is not the user’s healing and growth, although that may occur; instead, the work should be done in order to contribute to—or at least not interfere with—the healing and restoration of dignity to BIPOC. Proposing in her book’s title that readers can become “good ancestors,” Saad encourages her readers to do the work for others, not for ally cookies. She also suggests that the work isn’t doable if motivated by self-gain: “you will need something more powerful than pain and shame to encourage you to keep going.” The hope of growing into a good ancestor recalls Christina Sharpe’s call to white people to “lose your kin” and adrienne maree brown’s recent injunction that white people align with Mary Hooks’s mandate for Black people: to avenge the suffering of their ancestors, earn the respect of future generations, and be willing to be transformed in the service of the work. Whether Saad’s workbook—or any of these books—can produce their intended results is another matter entirely. Like any self-help guide practiced privately or in communion with others, from the Bible to The Power of Now, your mileage may vary.

As Cornel West has noted, writing and speaking to the broader (white) public about race is a time-honored hustle. That is not a reason to wholly discredit such work, but rather an observation as to where and how these dialogues circulate, and how we can bring them to spaces outside of capitalism. A crude Google Ngram search illustrates the rise and fall of “antiracism”: after a small but notable blip in the 1930s, it began to gain steam again in the 1970s, rose rapidly in the 1990s, and peaked in 2004. Its usage declined until 2012 (the year George Zimmerman murdered Trayvon Martin), and then it began another upward trajectory that has since surpassed the 2004 level and is still growing.

Thus, while antiracism is not new, it is resurgent, particularly in the publishing industry. The Antiracist Research and Policy Center, which Kendi directed, was scheduled to hold its 2nd Annual National Antiracist Book Festival this spring. Beacon Press, publisher of DiAngelo’s and Fleming’s books, is also the press of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations and has had a longstanding (though contested) commitment to progressivism and social justice. Its website includes resources for using the books as “lifelong learning” within congregations. The Christian church is a significant space for white people’s racial justice conversations in the United States. Books such as I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness by Austin Channing Brown (2018) and White Awake: An Honest Look at What It Means to Be White by pastor Daniel Hill (2017) were published by Convergent, an imprint of Penguin Random House that publishes books with a “faith” perspective, and IVP Books, an evangelical publisher, respectively. That these discourses of antiracism are reemerging through nonfiction monographs says more about the modes (private, literary, or parochial) which the public has been encouraged to engage with antiracism, than about antiracism itself.

White feminists have also played an integral role in publicizing these literatures to mainstream audiences, framing the books as combinations of self-help and feminist political theory. Seal Press, publisher of Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race, is a feminist press that publishes titles in support of (implicitly white, middle-class) women’s journeys; among them are How to Stop Feeling Like Sh*t (2018), The Guilty Feminist (2019), Average Is the New Awesome (2020), You Are a F*cking Awesome Mom (2019), Pretty Bitches: On Being Called Crazy, Angry, Bossy, Frumpy, Feisty, and All the Other Words That Are Used to Undermine Women (2020), and Cinderella and the Glass Ceiling: And Other Feminist Fairy Tales (2020). Alongside Oluo’s book, there are a few titles that center women of color , such as Arianna Davis’s What Would Frida Do? A Guide to Living Boldly (2020) and Cecilia Muñoz’s More than Ready: Be Strong and Be You. . . and Other Lessons for Women of Color on the Rise (2020). Prominent white women have also used their platforms to circulate this work. Eddo-Lodge’s book was embraced by Emma Watson’s digital book club Our Shared Shelf, while Saad’s book was blurbed by Anne Hathaway and Elizabeth Gilbert, of Eat, Pray, Love fame.

The literature of white liberalism continues to grow, even expanding into young adult, adolescent, and baby spaces. Saad’s book is coming out with a young reader’s edition, while Kendi’s Antiracist Baby board book debuted in June. Fleming’s Rise Up!: How You Can Join the Fight Against Racism is forthcoming in 2021 from Henry Holt and Co., an imprint targeted for ages ten to fourteen. It has also launched new voices into the mix: Asian American high schoolers (now Ivy Leaguers) Winona Guo and Priya Vulchi created antiracist educational materials that led to a listening tour, TED Talk, and the book Tell Me Who You Are: Sharing Our Stories of Race, Culture, & Identity (2019).

In the midst of all this, where are the men? Aside from Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist, the books covered in this review are all authored by women. Also, although Michael Eric Dyson’s Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon to White America was published by St. Martin’s Press in 2017, all this review’s books were published by small to mid-size presses or subsidiary special-interest imprints, and, save for Kendi’s and DiAngelo’s books, are marketed toward women. Curiously, the work of antiracism as a mainstream political project is often feminized, de-politicized, and ghettoized as women’s work, perhaps because it is so unwanted that it only reads as scolding force. (There are more antiracist K–12 educators than antiracist think tank economists, for example.) Antiracism is unwanted for the astoundingly simple reason that patriarchy rejects vulnerability, accountability, and transformation, preferring to uphold binaries between mind and body, thought and action, feeling and thinking, the group and the individual.

In this way, a book like White Fragility is discounted by the right for not accounting for individual agency, and waved away by the left as neoliberal self-help, preserving these binaries. Who or what, beyond the clickbait economy, is served by this insistence? While it is predictable that those on the right would take this tack, it is intriguing that so many left reviewers of White Fragility refuse to recognize its potential for cultivating radical relationality; instead, they are seemingly content imagining that racial (in)justice happens elsewhere, in the body of someone else (Bonilla-Silva’s “racism without racists”), or entirely via structural forces. To dismiss the cultivation of emotional awareness as New Age indulgence mischaracterizes relational work as depoliticized “personal” work, and wrongly suggests that such relational work is unnecessary to building progressive or radical futures.

It is also a reading that is behind the times. As Angela Davis noted in 2016:

I think our notions of what counts as radical have changed over time. Self-care and healing and attention to the body and the spiritual dimension—all of this is now a part of radical social justice struggles. That wasn’t the case before. And I think that now we’re thinking deeply about the connection between interior life and what happens in the social world. Even those who are fighting against state violence often incorporate impulses that are based on state violence in their relations with other people.

It is hardly shocking that liberals remain invested in capitalism. Far more concerning is that many leftists continue to innovate ways to remain invested in patriarchy and white supremacy by refusing to be accountable for white fragility and toxic masculinity.

In her comment, Davis nodded to North American practitioners of transformative justice, healing justice, and generative somatics, all embodied and communal political philosophies that critique Western, Christian, statist, liberal individualist modes of language-based adjudication and body-based punishment. Transformative justice understands sexual assault, for example, as a community problem with community-based solutions, not as solely an individual transgression that deserves carceral punishment. Healing justice engages things like the arts, sex, pleasure, rest, and ancestral wisdom as embodied modes of community-building and cellular transformation that allow for reflection and growth in social movements. These politicized forms of healing, justice, and transformation are unapologetically process-oriented, prefigurative, and de-accelerationist, uninterested in the erotic throb of “winning” that has undergirded mainstream millennial socialism. Pioneered in the past few decades by coalitions of Black, Indigenous, queer, trans, and women of color survivors, abolitionists, sex work communities, disability justice activists, mental health activists, artists, and healers, tenets of healing justice and transformative justice have emerged as guiding lights in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 uprisings.

Writer Estelle Ellison reminds us, “De-escalation skills, self-defense, community tribunals, accountability interventions, emergency response networks, and collective care are all strategies that help create more safety than any police force.” They are also anti-capitalist strategies developed by people unaccounted for by white-majority left formations, and rely on embodied, Indigenous, and ancestral knowledges rather than the disembodiment of the comrade or Eurocentric scientific socialisms. In Black Marxism (1983), Cedric Robinson is clear that revolution is more than its material conditions—that it springs from something metaphysical or unscientific in the Enlightenment sense. He argues that Black freedom struggles continue in the tradition of “a revolutionary consciousness that proceeded from the whole historical experience of Black people and not merely from the social formations of capitalist slavery or the relations of production of colonialism.” This has long been the Achilles’ heel of white-majority left formations: the decades-long split between white-majority left thought and minoritarian epistemologies like the Black radical tradition or feminist, queer, and trans of color left movements is simply an argument over whether difference is politically deadening or politically generative. (Or, in the words of Hamid Dabashi, “Can non-Europeans think?”) Yet the confidence in heterogeneous forms of the human that precede and exceed imperialism, capitalism, and white supremacist patriarchy—what Sylvia Wynter termed “the Human after Man”—is the basis for decolonial abolition.

The literature of white liberalism is obviously not a decolonial abolitionist literature. It succeeds by allowing the reading class to think about antiracism untethered from anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism. That is not to say that it has nothing to offer, nor that the authors are pro-capitalist shills. While all of these books offer sharp analyses of the way capitalism destroys Black and minoritized lives, they mention, but don’t center, the powerful critiques of capitalism issued by Black and minoritized traditions. This is something both white liberalism and white leftism have in common, despite being multiracial formations.

While all of these books offer sharp analyses of the way capitalism destroys Black and minoritized lives, they mention, but don’t center, the powerful critiques of capitalism issued by Black and minoritized traditions.

The literature of white liberalism is an antiracist technology that attempts to engender forms of white self-consciousness that can allow for more lubricated social relations. This is not bad in and of itself given the toll that aggressions, both micro and macro, have on the everyday lives of Black, Indigenous, and people of color. If white and non-Black people of color learned to take feedback on their anti-Black racism, imagine what else could be accomplished. But such change requires far more than reading. Importing these books into college classrooms and HR retreats does little if the structure of the organization is not also called into question; after all, classrooms and workplaces have never been safe spaces to undo white solidarity, especially for BIPOC. Alternate spaces of affinity and trust that intentionally imagine outside of capitalism are necessary for radical antiracist work. White-majority left movements—or at least their media correspondents—have shown themselves to be, so far, uninterested in decoupling antiracism from the workplace imaginary.

Antiracism’s historical entanglements and contemporary misadventures with liberalism are, to return to Jodi Melamed, “official antiracisms”—palatable, dematerialized forms of antiracism sanctioned by the state, capital, and elite institutions that crowd out radical antiracisms that refuse to disentangle racism from capitalism, patriarchy, and settler colonialism. Alarmingly, far too many critiques of the literature of white liberalism are willing to throw out antiracism itself in order to win a nihilistic woke war. In the end, multiple truths need to be articulated and held: “white fragility” is a satisfying term for an actually existing phenomenon; liberal antiracisms have never been enough; Black intellectual publics contain a multitude of perspectives; and white-majority left movements need radical relationality, now more than ever.