Looking back, even a fool would be able to predict it today: the Soviet regime could certainly have been breached only by literature. —The Oak and the Calf

Now that the human race has reverted with gusto to pre-1914 norms of hysterical religiosity and swaggering nationalism, it seems incredible that less than twenty years ago one-sixth of the earth’s surface was occupied by an atheist dictatorship that built up the second greatest military power of all time and, over seventy years, devoured millions of lives while claiming to be a people’s paradise in the making. And how much more incredible is the thought that this great historical aberration called the Soviet Union could have been brought down by one man sitting in a room, writing?

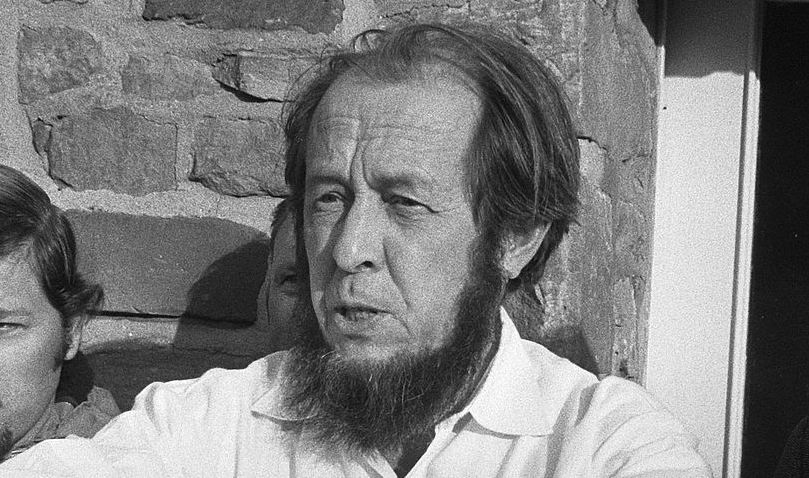

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who was that man, died last August 3, at the age of eighty-nine. No writer since Jean-Jacques Rousseau has had such an impact on the larger world. No writer felt a greater responsibility toward his art. No writer was more deserving of the respect of writers of all nations.

But at his death, Solzhenitsyn’s importance seemed mitigated by the length of his life; numerous media pundits pronounced him not only dead but irrelevant. Others decried his supposed Russian nationalism, religious intolerance, and self-aggrandizement. Most implied that he had, as it were, overstayed his welcome. “[Aleksandr Isayevich] outlived his era and never truly accepted the new ‘post-Soviet’ epoch,” opined the Russo-Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov. “Having sincerely dedicated his life to a desperate struggle against communism, [he] suddenly found himself without a battle to fight.” And Thomas Keneally, the Australian author of Schindler’s List, remarked: “Personal freedom, once he got it, didn’t give him a lot to write about. . . . in his way he was a creation of the Soviet system; that was his subject matter.”

True, up to a point. But systems, like fashions, come and go, and Solzhenitsyn was indifferent to them except to the extent they interfered with his freedom to write; and this is as it should be with a writer. Indeed, his extraordinary life, and equally extraordinary dedication to his art, should serve as example and inspiration to all writers, not just Russian ones, and not just because his three-volume investigative history and prose epic The Gulag Archipelago applied the coup de grâce to the Soviet system and, years earlier, shocked the West into awareness of the USSR’s true evils.

What brought a sense of mission to Solzhenitsyn’s life was primarily his conviction that writing matters. No writer has endured more in the service of his muse. Willingly, he would have given his life for his art, and nearly did, many times over. His art was his life, and vice versa.

In fact, Solzhenitsyn had not one life but several. The first was the Soviet life that began just after the Bolshevik revolution in 1918 in the provincial obscurity of the forested northern Caucasus (a place that resembles, in a nice bit of real-life literary foreshadowing, the hills of Vermont, the future exile’s future home). Amid ongoing revolution and imminent civil war, young Aleksandr Isayevich was raised by his mother, Taissa, not in that idyllic mountain landscape, but where there were industrial-era jobs: the smoky metropolis of Rostov-on-Don. She was a typist and stenographer and a cultured woman, widowed when her husband Isaaki, Aleksandr’s Cossack father, died in a hunting accident six months before Aleksandr’s birth.

In near-poverty—although, like so many families in those days, Taissa’s had been on the verge of prosperity when the Bolsheviks overthrew it all—she inculcated religious (Orthodox) and cultural (Russian) values in her five children. In Aleksandr, the former, despite baptism and frequent clandestine church services, languished after a while, to revive much later; but the latter bloomed immediately and enduringly. He read widely in Russian literature and history and absorbed via Tolstoy, Pushkin, Dostoevsky, and Turgenev his own sense of destiny and his country’s sense of exceptionalism, equaled only by America’s.

For him, as for most Russians, the world was divided into Russia and Not-Russia. This nationalist sentiment manifested itself in his early manhood as an attachment to Communism and the Soviet way. He was a model Young Pioneer and went on to become an accomplished student of mathematics and physics at the university in Rostov.

Mathematics was always his secondary passion and his primary hobby, his private playground. And he was good at it, both as a university student and, later, as a teacher. Although at university he took some correspondence courses in contemporary Soviet literature, he never shackled himself to such esoterica as literary criticism or creative writing, those luxuries of the Western academic beau monde.

What came to matter most to Solzhenitsyn was redemption through literature.

When his writing came, it came from his reading, his Russianness, and his soul, and it took time to mature; although, like most writers, he was goaded by his vocation from an early age. “Even as a child, without any prompting from others, I wanted to be a writer,” he said, “and, indeed, I turned out a good deal of the usual juvenilia.” He added, disingenuously: “In the 1930s, I tried to get my writings published but I could not find anyone willing to accept my manuscripts.” Plus ça change . . .

During those early years, there was no questioning of Soviet realities or unrealities. To all appearances, Aleksandr Isayevich was an ideal young homo sovieticus, a sober, industrious congregant of the Church of Marx and Stalin. He coasted under the authorities’ radar, which is where you wanted to be in Stalinist Russia, especially if you harbored literary (or indeed any) ambitions. Solzhenitsyn did, but kept them quiet. Still, like all young writers, he wanted an adoring somebody to assure him of the inevitable greatness to come, and in 1936, in Rostov, he found her: a pretty chemistry student and accomplished pianist named Natalia Alekseevna Reshetovskaya. In 1940 they married, but theirs was to be a splintered union, riven by jealousy and fate.

In 1941, soon after graduating from the University of Rostov with a degree in mathematics and physics, Solzhenitsyn was mobilized into the Red Army to fight the German invader. Bar the odd furlough, that was the end of all semblance of normal life. But Solzhenitsyn was always at his best in adversity, and the army was the least of his tribulations. He actually enjoyed it, in a way:

You read about the front line . . . when you are a boy and you wonder where people found such desperate courage. You cannot imagine yourself enduring so much. That was what I thought as I read Remarque (All Quiet on the Western Front) in the thirties, but when I got to the front myself I came to the conclusion that it is all much less difficult, that you gradually begin to feel at home even there, and that writers make it seem much more frightening than it really is.

He rose to the rank of captain, fought in the colossal battle of Kursk, and commanded a reconnaissance battery in East Prussia. In that most hellish of wars, he fought well for the motherland, being twice decorated (and certainly qualifying as a “hero” by today’s standard of definition). But in the cold, dreary, blood-soaked Germany of 1945, exhaustion, loneliness, the savage death throes of the German Army, and the eloquence of his pen got the better of him. He wrote a cantankerous letter to a friend in which he injudiciously slighted the greatness of Stalin, Generalissimo of all the armies, Red Tsar of all the Russias, whom he roughly referred to as “the man with the moustache” and upon whose military acumen he cast doubt. The letter was intercepted and read—how could he not have predicted it?—by agents of the Soviet internal counter-intelligence agency, that James Bondian outfit, SMERSH (an acronym for “Death to Spies”).

Despite the desperate need in the Red Army for accomplished and battle-hardened officers to help defeat the still-undefeated Nazis, Captain Solzhenitsyn was sentenced to the prison camps for a term of eight years, to be followed by lifelong internal exile, i.e., no visits to the bright lights of Rostov, never mind Moscow or Kiev. The humiliating shock of it all can hardly be imagined: the betrayal, the loneliness, the sudden metamorphosis from an authoritative member of society, one whom others respect and obey, into a nonperson and pariah, someone to be kicked around, despised, and left to die. “Arrest,” he later wrote, “is an instantaneous, shattering thrust, expulsion, somersault from one state into another.”

Thus began his second life, formed by imprisonment, loneliness, and exile. It ended in near-fatal illness—and triumph. Triumph over death because of incredible luck, and over despair and totalitarianism because of fidelity to his art. Solzhenitsyn was a writer: he wrote. He wrote even when he could not write.

I improvised decimal counting beads and, in transit prisons, broke up matchsticks and used the fragments as tallies. As I approached the end of my sentence I grew more confident of my powers of memory, and began writing down and memorizing prose—dialogue at first, but then, bit by bit, whole densely written passages.

His devotion to duty was the hinge upon which his life-story turned; it was the forge of his soul. It made him a man, and confirmed his evolution from vague scribbler to writer with a mission. And being a writer with a mission was a dangerous thing in the Russia of then; it is hard for us to imagine how dangerous. As Philip Roth famously said, referring to Eastern Europe under communism, “There, nothing goes and everything matters; here, everything goes and nothing matters.” What came to matter most to Solzhenitsyn was redemption through literature. Martyr that he was in his soul, he almost welcomed his suffering in its cause.

I hate to think what kind of writer I would have become . . . . if I had not been put inside.

He started his sentence at the Lubyanka Prison, one of those places, like Auschwitz, Bataan, and Île de Gorée, whose name is shorthand for horror. At first, Natalia Alekseevna paid daily visits to a public park nearby, hoping to catch a glimpse of him. Then the nightmare changed venue. Solzhenitsyn was put aboard an unheated railroad cattle car in the company of hundreds of others and sent without money or sustenance into the outer darkness of the work camps, what he later taught the world to call the Gulag Archipelago. It was a world of hidden, perpetual suffering that sprawled across Central Asia and Siberia and that contained, by the end of Stalin’s tyranny, around 2.5 million inmates, well over 500,000 of them “politicals“ like Solzhenitsyn. Nowhere else, except in the Nazi death camps, could the admonition Dante places at the threshold of the Inferno have been more apposite:

Abandon hope, all ye who enter here

Through me you pass into the city of woe:

Through me you pass into eternal pain:

Through me among the people forever lost.

Dante, of course, is the ultimate guide to hell, and Solzhenitsyn acknowledged this in the title of his first full-length novel, The First Circle; but from this point on, no better guide exists to Solzhenitsyn’s personal hell, and that of millions of others, than the three volumes of The Gulag Archipelago (published in the West in 1973, but not in Russia until 1989). Part Divine Comedy, part Baedeker, part Pilgrim’s Progress, it is a harrowing must-read, consisting of correspondence with 227 former zeks, or political prisoners.

In the book, Solzhenitsyn painstakingly describes the journey of the typical zek, like him, through the maze of the Soviet prison-camp system, details of which he fits into the overall “mosaic”—as he called it—with (to paraphrase Vladimir Nabokov) the precision of the artist and the passion of the scientist. But simultaneously—and here is The Gulag Archipelago’s true genius—Solzhenitsyn places along the way memorials to fellow inmates, homage to the millions who had gone before and who never returned. He names the nameless and reminds us that he is a traveler returned from farther away than we can imagine, although in some ways the Gulag was right next door.

We have been happily borne—or perhaps have unhappily dragged our weary way—down the long and crooked streets of our lives, past all kinds of walls and fences made of rotting wood, rammed earth, brick, concrete, iron railings. We have never given a thought to what lies behind them. We have never tried to penetrate them with our vision or our understanding. But there is where the Gulag country begins, right next to us, two yards away from us. In addition, we have failed to notice an enormous number of closely fitted, well-disguised doors and gates in these fences. All those gates were prepared for us, every last one! And all of a sudden the fateful gate swings quickly open, and four white male hands, unaccustomed to physical labor but nonetheless strong and tenacious, grab us by the leg, arm, collar, cap, ear, and drag us in like a sack, and the gate behind us, the gate to our past life, is slammed shut once and for all.

Part of Solzhenitsyn’s sentence was served in work camps in Kazakhstan, then known as the Kazakh S.S.R. During his imprisonment, he worked as a miner, foundry foreman, and bricklayer. The tension and brutality were relentless. In summer, when dust filled the air and lungs, temperatures of a hundred degrees farenheit or higher were common. In the blizzards and winds of winter, the thermometer often sank below zero. His experiences in that particular inferno—where the universe shrank to the size of a tin cup of warm, soupy water at day’s end—are captured in the vivid snapshot of camp life that is his landmark novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Standing there to be counted through the gate of an evening, back in camp after a whole day of buffeting wind, freezing cold and an empty belly, the zek longs for his ladleful of scalding hot watery evening soup as for rain in time of drought. He could knock it back in a single gulp. For the moment that ladleful means more to him than freedom, more than his whole past life, more than whatever life is left to him.

Ivan Denisovich is a book of haunting, almost intoxicating, simplicity of style, as bleak and beautiful as the steppes of Kazakhstan. When it was published in 1962, it made Solzhenitsyn famous. But it would never have seen the light of day, and we would likely not know the name of Solzhenitsyn at all, had another part of his prison sentence not taken him to Marfino, a sharashka, or scientific research unit run by the secret police, where he met Lev Zinovievich Kopelev, who was instrumental in the publication of Ivan Denisovich and whom Solzhenitsyn recast as Lev Rubin in The First Circle.

Kopelev was one of those writers so uncharacteristically well disposed toward another writer’s work that he risks his own reputation to publicize it. A linguist and scholar, he had taken the same bumpy road to incarceration as Solzhenitsyn. Yet he remained an idealistic Communist. He and Solzhenitsyn, by now a full-bore ex-Communist apostate, locked horns immediately. In the process, they became firm friends, or as nearly as was ever possible with Solzhenitsyn, who, like a saint, had no real friends: his mission was all. But he knew he needed others in order to accomplish it. No Kopelev, no publication, no freedom. (Kopelev himself died exiled in Germany, in 1997, an ex-Communist and devoted humanist.)

Even at Marfino Solzhenitsyn relied on Kopelev. The sharashkas were lifesavers for frail intellectuals. There, incarcerated scientists were required to work on arcane, frequently ludicrous projects, most of which represented some refined degree of the dictator’s paranoia. Solzhenitsyn was ordered to link his skills as mathematician and physicist to Kopelev’s as linguist in order to perfect the art of identifying voices overheard by telephone taps (all this is superbly told in The First Circle, which also features a cunning, manipulative Stalin, phone glued to ear).

But in 1950 the project came to an end, the (relative) idyll was over, and Solzhenitsyn was sent from Marfino to a “Special Camp” in the East for political prisoners. There he had a tumor removed, although cancer was not then diagnosed. That came later, with his third life: internal exile for life, ordered at the time of Stalin’s death in March of 1953 to a dusty place in southern Kazakhstan called Kok-Terek.

No sooner had he been released from years of imprisonment than he faced the unremitting misery of a) lifelong exile in a howling wilderness and b) “lifelong” meaning a matter of weeks, for it was at that time that he received a death sentence from his own body. Cancer, finally diagnosed, spread until it had nearly devoured him.

This was a dreadful moment in my life: to die on the threshold of freedom, to see all I had written, all that gave meaning to my life thus far, about to perish with me . . . . My friends were all in camps themselves. My mother was dead. My wife had married again . . .

Natalia Alekseevna, condemned to barrenness after her own bout of (uterine) cancer, divorced Aleksandr during the long years of his imprisonment. Uncertain whether he would ever be released, he had offered her her freedom; she, having met an easygoing man ten years her senior, was willing to take it. Alone in his Kazakh exile, Solzhenitsyn was doubly devastated. All the great venom of the world was unleashed on him. He was Job. He prepared himself for the end:

I hurriedly copied things out in tiny handwriting, rolled them, several pages at a time, into tight cylinders and squeezed these into a champagne bottle. I buried the bottle in my garden—and set off for Tashkent to meet the new year and to die.

Tashkent, Uzbekistan was where the authorities sent him to be treated, in a state cancer institute similar to the one he later described minutely in the haunting chronicle of promise and despair, Cancer Ward. Like one of his characters, Solzhenitsyn was told at first that he had three weeks to live, so he tried to arrange his thoughts accordingly. To combat the pain and the hopelessness, he did the only thing he could do: he wrote. At least he could actually sit down and put pen to paper, whereas back in the Gulag he was forbidden all writing materials and had to memorize everything. But what he wrote, mostly love missives to lost Natalia, expressed no more than his despair and spun away into the vortex of his despondency.

Then, at around the time previously appointed for his death, the doctors told him his tumor had gone into remission, and that he could reasonably expect to survive the next six months or so. They were conservative in their prognosis. He lived for another fifty-four years, through a combination of willpower, stubbornness, and blind luck. Radiation may have played a part in his cure, but he always attributed it to his self-medication with a concoction made from mandrake root . . . and to the will of God.

Solzhenitsyn’s illness and its miraculous healing ushered in his next life: the life redeemed. From this point on, he believed in something greater than himself. “[S]ince then, all the life that has been given back to me has not been mine in the full sense: it is built around a purpose.” These experiences shaped the indomitable soul of the man. It was during this decade that Solzhenitsyn, in a striking parallel to Dostoevsky in his Siberian exile, nurtured the quasi-mystical cultural and religious views of his later life, a not-quite-Orthodox Christianity that was more Russophilia, or at least Sovietophobia. (Tellingly, his autobiographical character in The First Circle, Gleb Nerzhin, identifies himself as a Socratic, not as a Christian.) He regretted what he had done as an ardent Communist and Red Army captain and compared himself with the inquisitors of the Gulag:

I remember myself in my captain’s shoulder boards and the forward march of my battery through East Prussia, enshrouded in fire, and I say: ’So were we any better?’

During the years of exile and thereafter, with his return to European Russia, Solzhenitsyn exulted in his renewed lease on life. Alone, he threw himself into his writing, bringing together personal experience, profound reflection, and hard-earned wisdom to produce a body of literature answerable only to eternity and deeply hostile to contemporary intellectual and political fashions. It was always a lonely battle. In the brief autobiography accompanying his Nobel Prize lecture, he wrote:

During all the years until 1961, not only was I convinced I should never see a single line of mine in print in my lifetime, but, also, I scarcely dared allow any of my close acquaintances to read anything I had written because I feared this would become known.

Such perseverance should shame writers who have nothing more to complain about than writer’s block or insufficient sales, some of whom even take their own lives in despair.

Solzhenitsyn’s post-exile period was one of austerity and solitude in his personal life. Although he and Natalia Alekseevna remarried in 1957, the marriage was as unsuccessful on the second go-round as on the first. She chafed for more liberty while, more than ever, he was immersed in his work. During the day he taught mathematics at a high school in Ryazan. In the evenings he wrote copiously and devotedly; the devil at your elbow soon disposes of domestic life.

Secure in his camouflage, he soon completed Ivan Denisovich, drawing on the best in modern Soviet writing—Yessenin, Gorky, Paustovsky—as well as on the more venerable traditions of the Russian literary greats of the nineteenth century. This confluence of traditions makes his writing, even in its less felicitous translated versions, remarkably lucid and easy to read; nowhere is this clarity and simplicity more obvious than in Ivan Denisovich:

Slap on the mortar! Down with the block! Press down! Check! Mortar. Block. Mortar. Block. . . . The boss had said not to worry about the mortar—chuck it over the wall and push off. But Shukhov wasn’t made that way, and eight years of camp life hadn’t altered him: he still worried about every little detail of work—and he hated waste. Mortar. Block. Mortar. Block. . . . ’We’ve finished,—it!’ Senka shouted. ’Let’s be off!’ He seized a hod and went down the ladder. But Shukhov—and the guards could have put the dogs on him now, it would have made no difference—ran back to have a look round. Not bad. He ran over and looked along the wall—to his left, to the right. His eye was true. Good and straight! His hands were still good. He ran down the ladder.

A worker’s pride in his work: in another context, standard Soviet stuff. (Khruschev is said to have especially enjoyed this passage.) But Solzhenitsyn makes good use of the socialist realist style, becoming in fact one of its finest exponents. What started as the timesaving economy of a writer in a hurry, under dual sentence from Gulag and death, was refined in the years of his internal exile into the concision of a master craftsman. It works, rendering accessible even the most harrowing and complex parts of his writing, which owes much to Zola and the French naturalists; but at its best there is a more relaxed, sleeves-rolled-up quality to Solzhenitsyn’s writing that instantly charms the reader. Take the rambling, summery beginning of his quasi-mystical short story “Matryona’s House”:

I was coming back from the hot and dusty desert, just following my nose—so long as it led me back to European Russia. Nobody waited or wanted me at any particular place, because I was a little matter of 10 years overdue. I just wanted to efface myself, to lose myself in deepest Russia . . . if it was there.

The style of this story, a Russian take on Flaubert’s “A Simple Heart,” is unadorned and colloquial and takes you right through to the tragic death of Matryona, a poor old peasant woman, a martyr to the materialism and selfishness of the age. Soviet critics deplored its “pessimism” and denounced its retrograde, non-socialistic qualities; quite unrealistic, they said. (Ironically, it was a barely fictionalized version of a real-life incident.) Still, Solzhenitsyn’s troubles with the critics—and we should remember that “critics” in the Soviet Union were usually party hacks and time-servers—did not start there. It was a running battle he fought all his life. Even in 1962 when Lev Kopelev got Ivan Denisovich published in the review Novy Mir (New World), there were grumbles of “bourgeois revisionism” amid the near-universal praise.

At the time, however, the forty-four-year-old math teacher from Ryazan, now revealed to the world as a novelist, felt, correctly, that he was at last getting his due. That Ivan Denisovich, with its bold use of socialist realism and its utter frankness in depicting camp life, had been published at all, let alone published uncensored, was a near-miracle in itself. Credit was due not only to Kopelev but also to Andrei Tvardovsky, Novy Mir’s editor and an accomplished poet. (Solzhenitsyn expressed his indebtedness then and later—in fact, devoting an entire section of his memoir, The Oak and the Calf, to the subject.) “You have written a marvellous thing,” said Tvardovsky. “You have described only one day, and yet everything there is to say about prison has been said.”

It was thanks to Tvardovsky and Kopelev, and in no small part to Nikita Khruschev, that Solzhenitsyn’s little book brought the Soviet system of prison labor to the nation’s—and the world’s—attention. It was the first crack in the dam of Soviet repression: a major piece of Soviet literature on a politically risky subject, written by a nobody from nowhere who had done hard time in the camps. It was also a literary tour de force, one of the gems of the age.

But even as the book was acquiring a worldwide reputation, in the Soviet Union copies were being pulped; the grumbling of the naysayers was swelling to a choir. Then came Khruschev’s fall in 1964, when the pendulum, having swung too far, swung back. Solzhenitsyn was pushed aside by the new hardline apparatchiks. “[Solzhenitsyn’s] work consists of lampoons on the Soviet Union that blacken the achievements of our fatherland and the dignity of the Soviet people,” snarled Pravda, at the behest of its new masters in the Kremlin. The time for candor in Soviet literature came to a close; it was back to the dreary illusions and the public lies.

And so began Solzhenitsyn’s life as a dissident. Despite the hostile climate, he tried, with the help of his friends Kopelev and Tvardovsky, to get Cancer Ward published, but they had first to get the approval of the Union of Soviet Writers. Enough said: the verdict was nyet, quoted straight from First Secretary Leonid Brezhnev himself. Not a literary man, Brezhnev on one occasion referred to Solzhenitsyn as a “hooligan” (a favorite insult of the Soviet power elite; dissidents were usually characterized as “hooligans,” “bourgeois revisionists,” or “lunatics”). Entire Politburo sessions were taken up by discussion of this now-famous hooligan. Solzhenitsyn’s following abroad, especially after The First Circle and Cancer Ward were smuggled out and published in the late ’60s in France and the United States, was his best protection against sudden disappearance of the kind the KGB specialized in.

This is what happened, Solzhenitsyn says; I know, I was there.

As the cultural thaw refroze, Solzhenitsyn’s marriage disintegrated once more, helped along by his fame after Ivan Denisovich and the concomitant horde of female admirers the former provincial schoolteacher acquired overnight. For a short time, he became an unlikely, and slightly ludicrous, Don Juan. “I have to describe lots of women in my novels,” Natalia Alekseevna later quoted him as protesting, lamely. “You don’t expect me to find my heroines at the dinner table, do you?” In 1970 they divorced again.

Two years later he married another Natalia, Natalia Dmitrievna Svetlova, a mathematician who worked a small miracle in his life. She quickly grasped the dynamics of her new household, which had soon grown by three: their sons Yermolai, Stepan, and Ignat. Thanks to his wife’s selflessness, Solzhenitsyn discovered that it was possible for a saint to be in love. Natalia Dmitrievna stiffened his spine in the face of KGB bullying; jointly, they issued a statement saying that no matter what threats were made, he and his family would not yield. The Solzhenitsyns became inspirational figures, no less so than the splendid Mstislav Rostropovich, the great cellist who had been sheltering Solzhenitsyn for years. Indeed, the bulk of The Gulag Archipelago was collated and written at Rostropovich’s dacha outside Moscow between 1968 and 1970. (In the latter year, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize, making him even more of a thorn in Brezhnev’s side.)

The completed Gulag Archipelago was already circulating in the Soviet Union in samizdat (underground press) form when it was launched from the Rostropovich dacha in 1973 and landed in Paris and New York with an impact heard around the world. No one was prepared for it. Not only was it a literary event, it thoroughly undermined the credibility of the once–powerful Communist Parties of the West, and dealt a mortal blow to the armchair communists of the Latin Quarter salons. Jean-Paul Sartre, buffoon-king of Left Bank Marxmen, sensing the imminent demise of his life–illusion, described Solzhenitsyn as “a dangerous element.”

He was partly right. A well-written polemic can be dangerous, but seldom does a polemic also qualify as literature, as Gulag does. In its pages Tolstoy meets Jonathan Swift. It combines epic-novel sweep, sardonic humor, pathos, and parody. As history, it alters fuzzy hindsight to 20/20 vision. This is what happened, Solzhenitsyn says; I know, I was there. As in every work of art, there are lessons in it for all of us. “Millions of Soviet citizens recognized themselves in his work,” writes Anne Applebaum, author of Gulag: A History. “They read his books because they already knew that they were true.” All his lessons are universal ones, drawn from close observation of human nature at its best and worst:

Power is a poison well known for thousands of years. If only no one were ever to acquire material power over others! But to the human being who has faith in some force that holds dominion over all of us, and who is therefore conscious of his own limitations, power is not necessarily fatal. For those, however, who are unaware of any higher sphere, it is a deadly poison. For them there is no antidote.

Not only was Gulag a runaway bestseller in the West, it was also being read in Russian over Radio Liberty and beamed into the Soviet Union. This was, of course, the last straw for the Politburo. “[The book] is a filthy anti-Soviet slander,” sputtered Brezhnev. “We have to determine what to do about Solzhenitsyn. . . . He has tried to undermine all we hold sacred: Lenin, the Soviet system, Soviet power—everything dear to us.” You can almost hear the sob in his throat. But Brezhnev held the reins of power, and in February 1974 he made his decision: Solzhenitsyn was thrown out of the country, his Soviet citizenship revoked. His family stayed behind, unable to leave until later.

Yet another life began: his second as an exile, his first away from his country. It began in Cologne, in the house of the German novelist (and 1972 Nobel winner) Heinrich Böll, author of Group Portrait with Lady and The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, whose works were widely read, ironically, in the Soviet Union. (How the two Nobelists got along is a matter of speculation. Warily, no doubt, with mutual respect but not much in common, bar a shared love of Beethoven, and of meat and potatoes washed down with beer.)

When Natalia and their sons joined him, Solzhenitsyn unburdened Böll and moved the family to Zurich, where he stayed for two years (and where he famously got cold feet and failed at the last minute to have lunch with Vladimir Nabokov) and wrote Lenin in Zurich, a masterful character analysis of the Father of the Soviet Union, in which some have seen also a self-analysis. Critical of Lenin as the central architect of what became Stalinism, he nevertheless narrates the novel largely from Lenin’s point of view, an “I” for an “I,” and not entirely unsympathetically. The novella was later folded entirely into Solzhenitsyn’s last great novel, August 1914, in which it forms the central chapters.

After Zurich came Cavendish, a small town in the southeastern corner of Vermont. There he lived from 1976 until 1994, unaware, always, that it was the best part of his many lives, because foremost in his mind was his return to Russia. It was fated; it had to be. “In a strange way, I not only hope, I am inwardly convinced that I shall go back,” he said. “I live with that conviction. I mean my physical return, not just my books. And that contradicts all rationality.” As did so much of his life.

But his time in Vermont was less an interim than an idyll. The rewards of years of sacrifice were finally paying off. He lived a writer’s dream-existence, with the world at his feet, his native Russia, far away, trembling on the brink, and his beloved family close around. His house, isolated in the woods with twenty acres of privacy around it, resembled his native Caucasus even down to the birch trees and the deer and the early October snows. Next to the main house, on a brook, he had a second dacha built for his writing and commuted between the two every day without fail. His wife and mother-in-law presided over the household and the one-man publishing industry he had become; here his sons grew up to become Russo-Americans, participating in both realities simultaneously.

Apart from one or two forays into the outside world—including his famous 1978 Harvard commencement address, in which he enunciated his low opinion of Western liberalism—he spent eighteen years isolated in his mock-Russia in Vermont, with no real desire to wander. Having already done so, he wanted only to write it all out. “I had had an amazingly rich and varied experience of life,” he said. “As a writer I did not need any addition to this experience but rather the time to process it.”

He turned to the work he regarded as his magnum opus, as if any opus could be more magnum than The Gulag Archipelago. The Red Wheel was the Russian Revolution meganovel that had been on his mind ever since he had read War and Peace at age nineteen, and that he had been working on intermittently since finishing Archipelago. Alas, in this reader’s opinion The Red Wheel all boils down to the first volume (Solzhenitsyn called them “knots”), August 1914; but that is sufficient. It is a truly magnificent work, the summit of his art, a gripping and lively narrative of the plotting and tensions that led to the assassination of liberal Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin and the first year of the First World War. It is a historical novel on a level with the best, with Tolstoy himself, to whom Solzhenitsyn always felt he owed a great—almost personal—debt. As with War and Peace, there is a “you-are-there immediacy to Solzhenitsyn’s recreation of a place and an age. An excerpt from any part of August 1914 will illustrate this point. Here, for example, is a street scene in Moscow, 1914:

A tramcar miraculously threaded its way through the narrow passage, though there was scarcely room for two drunks enlaced, and turned onto Vozdvizhenka, insinuating its warning clang into the clamor of the church bells up above and the general hubbub of the Arbat: the clip-clop of cab horses, the clatter of heavier hooves, the rumble of carts over cobbles, the cries of newspaper sellers, the solicitations of hawkers. Here, a cabby yells at a pedestrian: ’Get out of the way, can’t you!’ Over yonder a wheel has caught on the curbstone and the driver whips his horse: ’Gee up there!’

I subconsciously brush the dust of that hot day on the Arbat off my sleeve after reading this passage, through which the author’s hypnotic love of the time and the place shines so brightly.

The other volumes of The Red Wheel available in English, November 1916 and March 1917, are more run-of-the-mill sagas, with too much polemic, a wavering story line, and only now and then a leaping flame. The epic sold badly in Russian, when it finally came out. Mostly, at this point the fires were banked; the voyage neared its close. But in his years in Vermont, Solzhenitsyn also spun off tracts, letters, a rewrite of his acerbic and blackly humorous memoir The Oak and the Calf, and various and sundry pamphlets and monographs about the West, the Orthodox Church, Russia and the Jews (Two Hundred Years Together), etc.; a last processing of his several lives.

Such was the closure obtained in Vermont that his final life, begun on his return to Russia when it at last came about in 1994, was less an apotheosis than an anticlimax: exhilarating, at first, and a grand vindication of a long struggle, but ultimately an unsatisfactory reunion with his countrymen. Many of them had degenerated into mock-Westerners of the most money-grubbing sort and seemed indifferent to Solzhenitsyn and the higher values to which he had dedicated himself. He derided them for all that, but loved being among them all the same, a patriarch returned to his family. He ventured into the public arena (TV), where he did not belong; happily, he soon withdrew, his show canceled. He welcomed the revival of the Church, within limits. He proclaimed Communism, his erstwhile faith, dead for all time, and was annoyed at the stubborn survival of a rump Russian Communist Party. He made harsh comments about disheveled Boris Yeltsin, who embarked on “a national fire sale,” but was more admiring of buttoned-up Vladimir Putin who, Solzhenitsyn thought, at least tried to restore Russia’s self-respect.

But these were politicians, not writers, and ultimately Solzhenitsyn had no interest in them. He cared only for his art, and he never stopped working. The magnitude and majesty of what he wrote dwindled; like Tolstoy, in the late autumn of his life he contented himself with smaller things, the world in a grain of sand. But he never resisted the pull of the writer’s desk, never succumbed to the false excuse of writer’s block. Even with the Soviet Union vanquished, there still remained the great battle with the blank page, every day. He fought it unceasingly. For him it was an act of faith to end his frugal breakfast behind the closed door of his study. Beyond, in the wider world, the clamor went on. In his study, there was only the quiet page—his duty, and ours.

In the summer of his ninetieth year came the final, peaceful confluence of all those turbulent lives. One day he rose, went to work, and felt ill in the late afternoon. That night, in his bed, he died. Natalia Dmitrievna observed: “He wanted to die in the summer—and he died in the summer. He wanted to die at home—and he died at home. In general, I should say that Aleksandr Isayevich lived a difficult but happy life.”

He lived it for his art, and set an example for the ages.