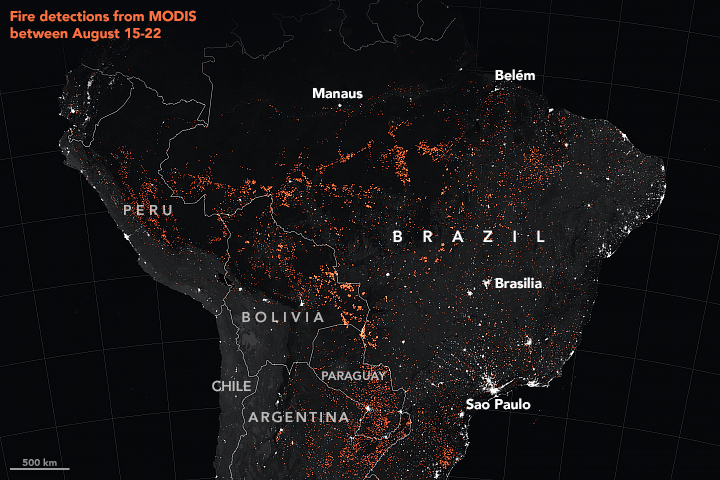

At 3 p.m. on Monday, August 19, in São Paulo, the skies of the normally smoggy city turned black in a scene that has widely been described as something from the Old Testament. Instead of locusts or end-times angels, it was ashes that blocked out the sun, having travelled thousands of miles from the thousands of ongoing fires in the Amazon.

The blackout was a visible reminder of what environmentalists and human rights advocates have been warning of for many months, and what was recently reiterated by civil society organizations in the region: President Jair Bolsonaro’s hollowing out of environmental and indigenous protections has incentivized deforestation in the Amazon for agricultural and extractive activities at a scale both unprecedented and possibly irreversible.

Scientists warn of a “tipping point” of no return for the Amazon. Untold numbers of indigenous people have suffered displacement. Ecocide is trending.

Indeed forest fires have nearly doubled in number compared to the same time last year, while deforestation has increased 50 percent, at a current rate of nearly one and a half soccer fields a minute. Scientists warn of a “tipping point” of no return for the Amazon. Untold numbers of indigenous people have suffered displacement and violence in frontier regions. The catastrophe threatens to have ripple effects well beyond Brazil’s borders. Ecocide is trending.

Bolsonaro’s anti-environmentalism should come as no surprise to anyone. He campaigned on an explicitly anti-environment platform and rode to victory on a wave of anti-establishment sentiment. He has rapidly dismantled institutions not only regarding the environment but also in education and health, as well as the country’s participatory councils. He spoke several times of not giving “one centimeter” to indigenous or maroon communities that enjoy some legal protection in the Amazon. Part of his original government program was to merge the Ministry of the Environment with the Ministry of Agriculture. And a loyal part of his base of support in congress has the so-called ruralist lobby, conservative politicians catering to oriented by commercial agricultural interests and hostility to the landless movement, indigenous land claims, and environmental regulation.

And while Bolsonaro did not abolish the Ministry of the Environment, for fear of international repercussions, he has essentially rendered it meaningless. He appointed Ricardo Salles minister, who denies the importance of climate change and, as director of São Paulo’s state-level environmental department, ran it into the ground and was convicted of manipulating environmental maps in favor of business interests. Under Salles the federal government has effectively ended environmental protection, turning a blind eye to illegal timber activity, land grabs, and deforestation. Moreover, the key agency in charge of environmental monitoring has been defunded, as has the one in charge of indigenous affairs. The Brazil Institute for Conservation has had its board replaced with military police officers. Dozens of agro-toxins were newly approved for use in Brazil this year, several of which are illegal in Europe. Bolsonaro has spoken in recent months of turning protected forest areas in Rio de Janeiro state into “Brazil’s Cancún.”

All this has given a green light to land poachers and others to slash and burn areas of the Amazon and invade indigenous lands and displace their populations. Brazilian media reported that on August 10 a group of farmers convened a “day of fire”—a series of illegal, coordinated efforts to burn down parts of the forest to plant pasture and make a symbolic show of support for Bolsonaro’s policies. In a recent case, poachers invaded part of indigenous Eru-Eu-Wau-Wau land and threatened to kill all of their children unless they left. In another, a group of fifty miners allegedly invaded Wajãpi territory and killed the tribe’s chief. And in perhaps the clearest sign of the times, a judge dismissed a case, despite video evidence, against a farmer who had been using pesticides on the Guyra Kambi’y tribe, seen by the prosecutor as chemical terrorism fashioned after the Agent Orange attacks in Vietnam. These attacks against indigenous populations come as political violence against social justice and environmental activists in the area escalates. That roughly 30 percent of the Amazon’s land is formally protected indigenous territory suggests just how much is at stake.

But Bolsonaro’s policies alone did not create the catastrophe in the Amazon: for decades undemocratic and conservative leaders of Brazil have used the Amazon as a trope to tighten their grip on power.

In the days after the blackout, Bolsonaro and his government found themselves in the middle of a controversy over their lack of response and their culpability in the fires. His environmental minister first claimed the fires were due to natural causes. To Bolsonaro, any suggestion that his government was not successfully fighting the wildfires was “fake news.” Earlier in the month Bolsonaro fired the head of the national space agency for discussing evidence of human activity in the current deforestation and suggesting that fires had increased by 88 percent from the previous year.

The Amazon fires have laid bare a lot about the Bolsonaro regime in Brazil: an unchecked pro-business orientation, a disregard for human rights, a disinterest in science, and an intolerance for dissent.

Another administration talking point has been that the international media has exaggerated the extent of the fires as a way to criticize the president. Bolsonaro himself, in what managed to be a low point in a presidency defined by public gaffes, blamed NGOs and then engaged in a weeklong social media battle with President Emmanuel Macron of France over the former’s pronouncements about the Amazon at the G7 meetings. While the spat ended with a juvenile Facebook attack on Macron’s wife, the incident reflects a longstanding wariness among Brazilian leadership that global concern for the Amazon constitutes a threat to national sovereignty.

While commercial interests clearly stand to make fortunes with cattle, timber, and mining in the Amazon, it is critical to understand that the region is also vitally important to conservatives in Brazil. Why, for example, does Brazil’s current minister of foreign relations see the threat of global warming as a concoction of “cultural Marxists,” and why do military figures in the government, including the vice-president, repeatedly accuse foreign countries of interfering against national sovereignty when they speak of the fires?

But Bolsonaro is just the latest in a long lineage of leaders in Brazil with developmental designs on the Amazon, going back to the early part of the twentieth century. This was true of Getulio Vargas (in power 1930–1945), who spoke of the bringing settlement and development to the region, and was even more pronounced in the dictatorship period (1964–1985), when military leaders made a concerted effort to occupy and develop the region, opening up roads and mineral extraction, and incentivizing migration of farmers from the South of the country—all in a bid, as the generals said, to “flood the Amazon with civilization.” Part of the military’s ideology held that occupying the region was a national security priority to prevent encroachment from other countries. Since the rise of democracy in 1985, environmental gains have been timid, owing to the largely unchecked power of landholders on successive governments. Nonetheless, indigenous claims to land, protection, and rights found traction during the left of center Workers’ Party national administrations. During Lula’s presidency (2003–2011), and the first years of Dilma Rousseff’s (2011–2016), the rate of deforestation was significantly reduced owing to increased policy efforts. Both trends today are in rapid reversal.

But Bolsonaro is just the latest in a long lineage of leaders in Brazil with developmental designs on the Amazon, going back to the early part of the twentieth century.

Beyond that, there is an even more extreme view that has been circulating in Brazil, particularly in military and far-right circles, since at least the 1980s. They claim that internationally funded NGOs are part of a globalist conspiracy to undermine Brazilian sovereignty in the Amazon: indigenous land protections are a farce based on grossly overestimated numbers of indigenous people and invented tribes, such as the Yanomami, who are said to be an European concoction from the 1970s. And they argue that this weakens Brazilian business interests while also weakening the Brazilian nation-state. Environmentalism is thus construed as thinly veiled leftist ideology, while environmental NGOs are in alliance with foreign powers. In this account indigenous people are variously portrayed as childlike pawns in schemes they don’t understand, or dangerous savages who stand in the way of the country’s progress. These views continue to find traction, particularly in social media, where it has circulated that there are 100,000 NGOs in the Amazon.

Later this month Bolsonaro will arrive in New York to open the United Nations session, one incidentally devoted to climate change. He will certainly face international condemnation. But will it be enough?

The Amazon fires have laid bare a lot about the Bolsonaro regime in Brazil: an unchecked pro-business orientation, a disregard for human rights, a disinterest in science, and an intolerance for dissent. It reminds us of the long and sad trajectory of designs on the Amazon. When Bolsonaro or his cabinet blame NGOs or indigenous land protections for the Amazon fires, or when he alludes to shadowy globalist interests in the region, he is trafficking in paranoid and deeply racist conspiracies. He is stoking people’s worst sentiments and giving license to the kinds of attacks on indigenous people. Undoing all of the causes of the catastrophe—the business interests, the dismantled state, the open racism, the twisted nationalism, the war on dissent—make for a difficult task, but one we cannot avoid.