Lindy’s Diner in Keene, New Hampshire, is a regular stop for would-be presidents. Situated just off Main Street, across from the bus station, it looks like the platonic ideal of the form: plate glass, chrome, red vinyl. It would be kitschy if it weren’t also a bit tattered. They say no one has made it to the White House without dropping in at Lindy’s on the way. It was, accordingly, item number one on Ted Cruz’s Martin Luther King Day agenda, as he dove into a seventeen-stop tour of the first-in-the-nation primary state.

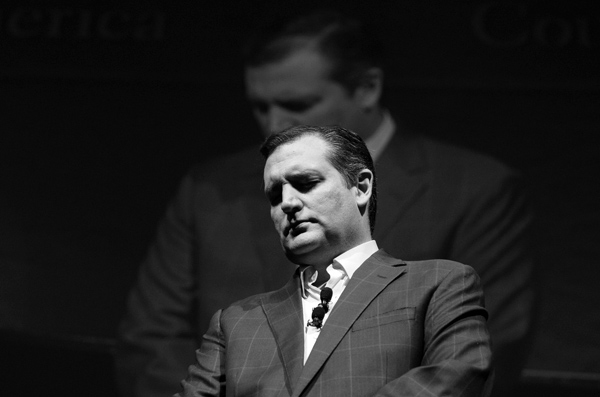

When I arrived at Lindy’s, Cruz was inside, looking casual in a blue sweater and no tie and speaking to a battallion of cameras, fuzzy microphones, and notepads.With reporters cramming the floor, few spots inside the small diner could have remained for the locals Cruz was meant to meet and greet. I slipped in the backdoor.

After the press let go, I edged close enough to catch Cruz’s eye amid the throng of camera phones. He turned my way. This was easier than I expected. We shook hands, and I asked, “What did you think of the Brooks piece in the New York Times?” David Brooks had just written a widely read column, “The Brutalism of Ted Cruz,” which argued that, despite his popularity with evangelical Christians, Cruz is in fact profoundly unchristian, embracing a “pagan brutalism” of belligerence and hate rather than the Christian virtues of mercy, compassion, and grace. If Cruz was surprised by my question, he didn’t let on. Oh, you know, he said. “It’s the New York Times.” He shrugged with his eyes: what do you expect.

For some evangelicals, Cruz’s spiritual convictions align with Trump’s material ones. Both pursue the destruction of God’s rivals on earth.

I thought Brooks had missed something important, and I wanted to know if Cruz agreed. What Brooks had discounted was the possibility that Cruz’s “fear-driven, apocalypse-based approach” was not unchristian at all but may in fact rest on a core commitment of evangelical doctrine: spiritual warfare.

“Does the logic of spiritual warfare explain what Brooks sees as your brutalism?” I asked.

Cruz didn’t blink. “I believe in Ephesians,” he said. “We need to put on our whole body armor.” He has said the same thing to supporters and campaign volunteers—the “strike force,” as he calls them. I continued, asked if we always need to be on the lookout for the Devil, if spiritual warfare explains what’s going on in this country. “This nation is under attack,” he answered, “and it’s only going to get worse.”

Our time was up. “God bless,” he said to me, and he seemed to mean it. Then he moved on to the next camera phone.

In the wake of George W. Bush’s presidency and Barack Obama’s election victories, it was fashionable to say that evangelical Christians had run their course as a force in American politics. In 2008, the once-powerful voting bloc didn’t deliver. Soon, the avatar of the right would shift to the Tea Party, which accommodates evangelicals but is hardly synonymous with them. While evangelicals became absorbed into other coalitions, the Tea Party proved its muscle in midterm defeats of Democrats and moderate Republicans alike, and in its overthrow of House leaders John Boehner and Eric Cantor.

The current election cycle looks different, though. The top GOP competitors, Cruz and Donald Trump, are working hard for evangelical votes.

This comes naturally to Cruz, whose talk of Ephesians demonstrates an affinity for the New Testament book that lays out the central tenets of spiritual warfare. In Ephesians, Paul warns believers to “put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the Devil.” He instructs Christians to fasten on the “belt of truth,” the “breastplate of righteousness,” and the “helmet of salvation”; to take up the “sword of the Spirit” and the “shield of faith.” With these weapons, the faithful guard “against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.”

For many evangelicals, spiritual warfare is the fundamental organizing principle of the cosmos. It is not difficult to see how our current landscape of unpredictable violence, in which people are shot at the movies, at Christmas parties, in classrooms, at concert halls, and in cafés can reinforce this cosmology. Don’t understand what’s happening in this crazy world of ours? An eternal battle between good and evil. Don’t know whom to blame? Blame Satan.

It is therefore no surprise that Cruz describes everything, in Brooks’s words, “as a maximum existential threat.” For him and millions of evangelicals like him, everything is a major existential threat. In order to destroy the Devil, we must destroy all of his demonic projects, be they the EPA, Planned Parenthood, the IRS, or ISIS. For an evangelical grounded in the language of Ephesians—not to mention scores of modern guides and other books of the Bible, Old and New—this uncompromising, militant rhetoric is utterly Christian and utterly recognizable. It may be brutal, but there is nothing pagan about it.

Trump’s evangelical pitch is more forced. One suspects the well-worn Bible he waved in a January 18 speech at Liberty University came from his campaign’s props department. The assembled students giggled when he flubbed a biblical citation, referring to “Two Corinthians” instead of “Second Corinthians.” While Trump attends church occasionally, he does not belong to any particular one. He is a main-line, middle-of-the-road, Presbyterian with what he promises is “a great relationship with God.”

And yet, Jerry Falwell, Jr., heir to the Moral Majority founder and successor as Liberty University’s president, has endorsed Trump. Polls show that Trump is beating Cruz for the evangelical vote. How can that be? A New York Times report notes the confusing implications: “Brash, thrice-married, cosseted in a gilded tower high above Fifth Avenue and fond of swearing from the stage at his rallies, Mr. Trump, who has spent his career in pursuit, and praise, of wealth, would seem an odd fit for voters who place greater value on faith, hope and charity.”

But, in fact, the polls are not so hard to make sense of if we recognize that evangelicals are motivated by more than emulating the virtues of Christ. Many, if not most, are also motivated by fighting the evils of Satan. While Cruz may better understand the doctrinal origins of that conflict, the two men locate the forces of evil in some of the same terrestrial enemies—their logics may be different, but they are pushing the same fight.

Chief among those enemies appears to be Islam. In Cruz’s cosmology, not just Islamic extremists but Muslims themselves are the threat. After President Obama remarked in his State of the Union address that “ISIL does not speak for Islam” and lauded “millions of patriotic Muslim Americans who reject their hateful ideology,” Cruz made the equation Obama refused, accusing the president of spending “a significant portion of his Sunday address as an apologist for radical Islamic terrorism.” This from a candidate who calls himself a “Christian first, American second.” Trump wouldn’t likely make the same claim, but the two candidates have offered similar xenophobic proposals to ban Muslims from entering the United States. And if you share Cruz’s spiritual convictions, there is nothing wrong with Trump’s material ones. Both pursue the same ends: the destruction of God’s rivals on earth. Trump’s catnip—his addictive blend of optimism and anger, his bluster, his imperious outsiderness, his speaking truth to power (or power to truth, as the case may be)—isn’t made only for evangelical Christians, but there is no reason it can’t appeal to them.

Clearly, any initial assumptions that evangelical voters would back Cruz over all comers have long since been thrown out the window. This makes sense. Evangelicals are not monolithic; the notion of “evangelical voters” is slippery to begin with. Scholars of religion will say, “For the purposes of this study, X will be understood as Y,”but what exactly counts as evangelical in the popular imagination is hard to nail down. NPR’s Danielle Kurtzleben raised this very point recently, noting that the definition of the “squishy” term “can vary from person to person, or even from pollster to pollster.” Indeed, “depending on the method of measurement, more than one-third of Americans are evangelical, or fewer than one-in-10 are.” It doesn’t get much squishier than that.

Even those evangelicals who share Cruz’s zeal for spiritual warfare may not find much to like in his Islamophobia.

Yet, a kind of patronizing dismissiveness informs our expectations of how evangelicals think. When we are dumbfounded by evangelicals who don’t behave the way we expect them to, we need to remind ourselves that just as blacks did not, to a voter, support Barack Obama, and just as there exist women who will cast ballots for Bernie Sanders and not Hillary Clinton, evangelicals will not be confined by easy identity boxes.

Even those evangelicals who share Cruz’s zeal for spiritual warfare may not find much to like in the Texan’s militant Islamophobia—or, for that matter, Trump’s. This is because they differ when it comes to the process called discernment, whereby one reads the spiritual landscape and figures out where Satan is to be found and what he is up to.

Which obstacles in your life are the terrestrial representations of Satan’s evil? What temptations is he sending your way? How do you recognize a wolf in sheep’s clothing—distinguish good from evil when evil is so skilled at coming up with clever disguises? Evangelicals are not all supporting Cruz, in part, because they do not all see demonic activity in the same places he does.

A case in point is the evangelical magazine Christianity Today, which recently urged readers, “However you vote this year, don’t be motivated by fear.” “Satan and his minions torture believers by provoking them to abandon their trust in God and bury themselves under the weight of fearful circumstances,” the authors argued. Demons constantly bombard Christians with temptations to be afraid. Fear “deceitfully whispers the first lie spoken in the Garden of Eden—your Creator is not a good Father.” Fear is “momentary atheism that denies God’s goodness, his ability and his plan.” In other words, Satan is acting through certain unnamed presidential candidates who are appealing to fear and thereby encouraging supporters to doubt God.

If Satan is in the eye of the beholder, then the logic of spiritual warfare can lead to more than one conclusion. Some see the Devil’s work in the fear of all Muslims that Trump and Cruz have reinforced with their calls to limit Muslim entry to the United States. Some see the devil’s work in radical Islam and Muslims themselves.

What Cruz and Trump are saying sits squarely in the wheelhouse of the latter sort of evangelical. Be afraid. Bad people and evil forces are out to get you. Fight back. That is the logic of spiritual warfare. Cruz may have perverted this logic so that the means of fighting back go far beyond the spiritual arsenal offered in Ephesians, and Trump may be unaware of it entirely. But this doesn’t matter. Christians who applaud when their pastor tells them, “Islam is a false religion, and it is inspired by Satan himself” hear both candidates speaking their language.