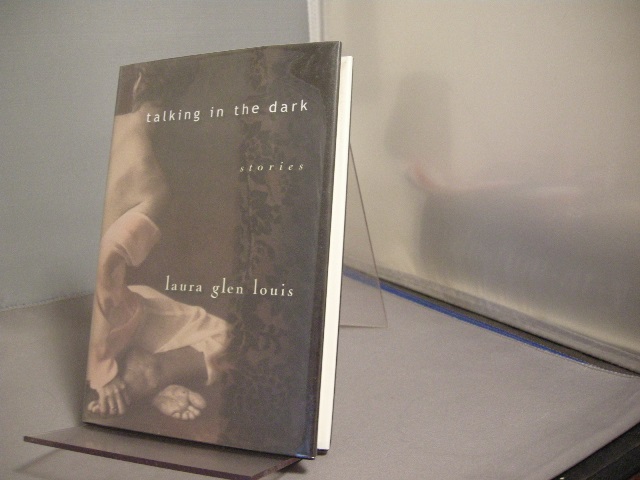

Talking in the Dark

Laura Glen Louis

Harcourt, $23 (cloth)

Some years ago, Laura Glen Louis attended a talk by Grace Paley at which a member of the audience eagerly asked, "Ms. Paley, when are you going to write a novel?" "Never," Paley replied. "I don't like people to skim. And in a short story they can't." Well, some readers will always skim, but with a Paley story (and she never has written a novel), that's roughly equivalent to looking at a Vermeer for ten seconds. You need longer than that just to absorb the stillness. Paley, whose highly elliptical but emotionally freighted stories set the standard for many writers in the 1970s and '80s, is surely a model for Louis, as are Don DeLillo, Joan Didion, Italo Calvino, and William Trevor. All are writers who defy the lazy reader, the skimmer, the quick-fix literary hedonist impatient for the rush of plot and resolution. Hearing Paley confirmed Louis's growing devotion to the short story. She recognized "what every story writer knows: shorter is not only better, it's a great deal harder."

The result of her epiphany—and her determination (raising a family and caring for a dying parent, she often had only quarter-hour intervals for writing)—is a debut collection of lean, sinewy prose and tightly compressed emotional implications, all related to matters of the heart. Her technique hinges on the unarticulated and the tenuously suggestive, even the subliminal. This kind of restraint can sometimes seem so willful it ceases to be artful, and the book's opening story, "Tea," where characters are little more than names and a single metaphor frames the anemic narrative, is not auspicious. A woman named Sheila, disappointed in a love affair with a cipher named Chapman, leaves home and flies to Japan. Before she goes she has the rather commonplace insight that "in the time it took to make tea, the direction of a person's life could change." Not long after, in a pavilion in Kyoto, she attends a tea ceremony that involves considerable bowing. In the story's last words Sheila reasons that "bowing takes even less effort than making tea. One could think of it as a calling." An aphorism seems a facile way to end a story that already has limited resonance and a bafflingly truncated structure. You don't have to skim "Tea" to feel you're missing something vital.

But the reader should persist. Whether by design or not, the collection has an impressive arc. There are only eight stories, with the first and last by far the weakest. ("Divining the Waters," the concluding piece, is a rambling semi-sequel to the penultimate story and unsuccessfully attempts the kind of dovetailing texture that Alice Munro has virtually patented.) In between are stories of deepening subtlety, more delicate characterization, and an intensity of feeling all the more persuasive for staying below the surface. These middle stories also show extraordinary discipline and craftsmanship. Although few of the pieces in Talking in the Darkhave previously appeared in journals or quarterlies, Louis's first published story (not included here) won the Katherine Anne Porter Prize, and her work has been featured in Best American Short Stories. Like the Porter of Flowering Judas, she is "drawn to economy." She continues, "I like clean design, simple lines. I wish I could write a story as elegant and straightforward and timeless as a little black dress."

Love, in a word, is Louis's subject, and she is no romanticist. Love is not simple, elegant, or straightforward, and rarely timeless. Love, she says, "is messy." In "Fur," an elderly, lonely, and wealthy widower, Fei Lo, begins to date a young teller at his bank and becomes increasingly fond of her. At first she seems attentive and sincere enough, but she is actually a golddigger. While he naps, she pokes around his wife's old bedroom, kept like a sanctum sanctorum, and eventually takes a mink coat from the closet. Discovering the theft, and the girl's true nature, he is thoroughly disillusioned. Louis leaves him standing alone in the night—he who was always a lover of the sun. The story's last paragraph is perfect in its poignant lucidity:

He counted all the stars that he could see, and when he was finished, he felt confident that if he stood there a bit longer he would spot another. And another. The price for such clarity was just the cold, the pure cold of a clear night. Fei Lo paused to savor its kiss and sting.

Fei Lo is treated with a bit more humor than is usual in Louis's characterizations. More often she presents her men and women with such a penetrating, somber empathy that a deliberate affective claustrophobia seizes the reader. "Her Slow and Steady," about a couple who have lost a baby daughter to SIDS, is a story we have heard before, in versions more and less maudlin. In it, the grieving parents, Bert and Grace, say little directly to each other. Mutual consolation is hardly a possibility, and love in itself does not heal. The hope that Louis suggests for them is oblique, provisional. It's a story so motionless—music is the only real punctuation—that sorrow comes in on the lightest breeze. Louis puts all the pain in the silences, and in a few objective correlatives that barely register on the consciousness. The effect is like a kindertotenlied.

As the crib-death incident indicates, Louis is attuned to the sudden and inexplicable. In "Thirty Yards," a menacing tale of obsessive love, Mrs. Chang appears, in the beginning, to be a major character. For several pages she dominates the story. Then, in a succinct, comma-less sentence worthy of E. M. Forster or Muriel Spark, fatality bites. "She left the hospital after her shift and a swerving car struck her dead." Ironically, Mr. Chang notes that his wife was always tormented by "her own limitations to protect." Now their daughter is being stalked by a deranged suitor, and a thirty-yard restraining order may not even save her:

Christine knew what thirty yards truly signified. At a practice range, and for handguns, thirty yards was the average distance between the shooter and his target. With a rifle, thirty yards would be a challenge only if the shooter didn't take aim.

In other stories, love is less incendiary but still treacherous. Marital disintegration and dissolution are the themes of three stories, two of which deal with husbands leaving their wives for younger women. The more harrowing of these is "The Quiet at the Bottom of the Pool," and Rosemary Berg, its central figure, may be the most haunted and complex woman in Louis's book. Deserted, desperate, confused, and lonely, she sleeps with her daughter Babette's teenage boyfriend Buck, a boy so close to the entire family the act borders on the incestuous. There is a strong implication that Rosemary feels—or has channeled—more anger toward the blasé Babette (who suggests her mother date a man she figures is "good size") than toward her philandering ex-husband. Worse, she knows she is aging. Her Buck will be as faithless as an ephebic Lothario in a Colette novel.

Rosemary's anguish constitutes one of the more openly sexual stories in Louis's book, but in no story is sex described or analyzed. Only in "Tea" is it even glimpsed. Once, however, Louis tried her hand at erotica. She admits in a personal essay to having thought "in a moment of high arrogance" that it would be a snap. She decided on a totally clichéd plot: "a woman, her doctor, an affair." Examining the product later, she thought, "let's just cut out all the sex." Her instincts were right. "Talking in the Dark," the unalloyed story that remained, is her finest piece here. There isn't a whisper of emotional compromise in it. The woman and her doctor, Claire and Russell, meet on neutral ground in another doctor's house. They first connected in Russell's office, where Claire said to him, "When patients come to you, we're not fine. We're ill, we're hurting, we're anxious. You walk in with your chart and pen, we're practically naked." And he said to her, "The first time I saw you, your eyes were closed and you were singing." The hearing daughter of deaf parents, Claire learned to sign before she learned to speak; now she's in a chorus, singing the Fauré Requiem. Her husband has left her and her daughters, perhaps never to return. Of his life, Russell says, "I love my wife. I love my children. I've spent some forty years being a reasonable man and it no longer comes naturally." Through the evening, the single evening that comprises the story, they talk. The story ends with Russell—and the reader—wondering if Claire had held his hand, or smiled before leaving. Speaking, signing, touching, smiling, singing, silence: language, connection. And all of it mysterious.

Laura Glen Louis came to America from Hong Kong when she was five. Cantonese was her first language, and she occasionally sprinkles her very precise English with it. Understatement seems to come naturally to her. Economy is her watchword. Like Grace Paley, she doesn't want to be skimmed. Unlike her, she is working on a novel.