Clare Cavanagh,

Lyric Poetry and Modern Politics: Russia, Poland, and the West.

Yale University Press, $29.95 (paper)

Irena Grudzinska Gross,

Czesław Miłosz and Joseph Brodsky: Fellowship of Poets

Yale University Press, $40 (cloth)

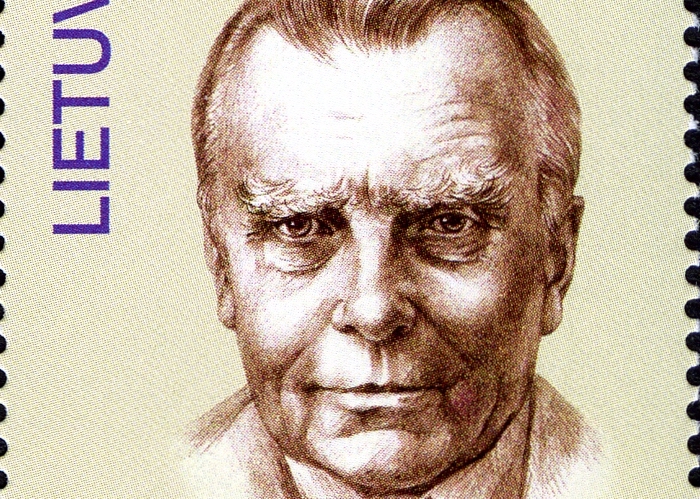

This year is the one hundreth anniversary of the birth of the Polish Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz, an occasion that is being celebrated with festivals and conferences across Europe and North America and with the publication, somewhat belated, of Miłosz’s Selected and Last Poems. Difficult as it is to predict how an author who is much admired today will be read in another hundred years, Miłosz is well on his way toward literary canonization.

The question is whether American readers, long accustomed to reading Miłosz as a witness to Nazi and Communist crimes—his World War II poems and his critique of socialist realism, The Captive Mind, are easily his best-known works in English—will be able to assimilate the larger, more complex, and necessarily more ambiguous version of the work that inevitably emerges in the course of a posthumous life. We have not yet accurately traced, let alone understood, the path that led Miłosz from the blood-curdling historical ironies of “A Child of Europe,” a poem about the generation of survivors who “sealed gas chamber doors” and “stole bread,” to the far-flung philosophical searchings of his jeans-clad Berkeley decades, to the late poems of grief and humility cast in a framework of theological reflection.

Clare Cavanagh’s Lyric Poetry and Modern Politics, which received the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism in 2011, strikes one powerful blow in favor of reconsidering Miłosz; Irena Grudzinska Gross’s Czesław Miłosz and Joseph Brodsky: Fellowship of Poets strikes another. Cavanagh is especially interested in how Western readers’ political and historical obsessions in the postwar period have molded a particular vision of Miłosz and his compatriots—a vision clouded by a peculiar mixture of awe and, in the case of American poets, envy of the authority still granted Polish poets and poetry. Cavanagh calls that vision a “Polish complex,” with Poland “as a kind of Slavic shorthand for ‘The Oppressed Nation Where Poetry Still Matters.’” In Cold War Poland, after all, poetry that had been honored with a state ban passed from hand to eager hand, and poems—Miłosz’s, Zbigniew Herbert’s—were memorized and served as moral touchstones in an era of official lies.

Though in the West Miłosz is seen as a defining Polish poet, he has always been a controversial figure in his native country, and he continues to provoke public debate and tendentious views seven years after his death. In the eyes of the right, his stint in the diplomatic service of Communist Poland in the 1940s is a permanent stain on his reputation, and his critical stance toward Polish nationalism and xenophobia earns him new enemies in each generation. Conservatives still like to point out that Miłosz was born in Lithuania and spent half of his life in emigration. What kind of a Pole was he, anyway?

More attendant to the poet than to the discourse surrounding him, Grudzinska Gross focuses on Miłosz’s friendship with the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky, another Cold War castaway, also the recipient of a Nobel Prize and subject to a complex similar to that which Cavanagh describes. Both authors provide critical insights that may—and certainly should—reshape our reading of Miłosz and Brodsky for years to come.

While much has been written about Miłosz’s relationships with American and international luminaries, Grudzinska Gross is among the first to provide English-language readers a solid account of how his orientation toward language—and, therefore, toward his audience and his own authority—was changed, complicated, and ultimately enriched by exile, how he made exile work for him both spiritually and professionally. She is exceptionally good at putting spiritual developments in a clear historical context, rendering visible and palpable those more elusive “matters” that Adam Zagajewski tells us, in a line that Grudzinska Gross takes for her epigraph, are “transparent like gauze.” She deftly shows how exile was itself the extreme stage of a process of social deracination and political upheaval in Eastern Europe, which had encouraged a near-complete identification with language (rather than class, family, or religion) before Miłosz or Brodsky even left home. Miłosz’s own remarkable clarity on this point is apparent in the 1972 letter he wrote to Brodsky, then living in Ann Arbor, that initiated their long association:

I think that you are very worried, like all of us from our part of Europe—brought up on the myth that the life of a writer ends if he abandons his native country. But it is only a myth, understandable in the countries where the civilization long remained a rural civilization and “the soil” played a great role.

As if to evidence the letter’s power as a gesture of friendship, it is the only text we have from Miłosz in Russian.

Grudzinska Gross’s book is itself an act of friendship, cognizant of Rilke’s observation that “works of art are of an infinite loneliness and with nothing to be so little reached as with criticism.” Her readings show a warmth rare in scholarly texts, even if this means that for a consideration of more technical matters, the nitty-gritty of poetry, a reader must go elsewhere.

Miłosz urged Brodsky not to despair ‘the myth that the life of a writer ends if he abandons his native country.’

Above all, Fellowship of Poets examines the idea of poetry as a moral force in history, embodied in relationships both hierarchical—between poet and reader, teacher and student—and fraternal. For these particular poets, who met when Miłosz was in his 60s and Brodsky in his 30s, the friendship seems to have run a precarious course between mentorship and rivalry, and some of Grudzinska Gross’s most penetrating—and wittiest—insights pertain to how the two negotiated the balance of power between them.

Against the Western habit of placing Eastern European poets on the same page politically (for the simple reason that this is where anthologies place them), there is a revelatory account of Miłosz and Brodsky’s tête-à-tête at a literary conference in Lisbon in 1988, one of the few occasions when the two were publicly at odds. Miłosz accused Brodsky of supporting the principle of divide et impera—“divide and rule”—in denying the reality of Central Europe as a region unified by its subjugation to Moscow. Brodsky protested rather unconvincingly, disarmed by Miłosz’s repeated insistence that this was a disagreement between friends. Grudzinska Gross gives a valuable and subtle commentary on the shades of irony at play in Brodsky’s own use of the word “imperium,” claiming that he learned the stance of the empire’s cynical observer from Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s most famous Romantic poet. Like Pushkin, Brodsky tended to make the figure of the tyrant, rather than the fact of empire, the object of his scorn, continuing to take pride in the grand scale of the Soviet Union and its history while adopting an ostensibly apolitical attitude. “Freedom,” he writes in a poem that carries that title, “is when you forget the spelling of the tyrant’s name.” It is difficult to imagine Miłosz, or any Pole before Zagajewski, writing that line.

The American edition’s cozy subtitle, “Fellowship of Poets,” evokes the self-congratulatory backslapping atmosphere Miłosz and Brodsky moved in during their post-Nobel years. The Polish edition has a different subtitle, “Magnetic Poles,” which would have made for an unfortunate pun in English but neatly combines the book’s two important lines of inquiry: the basis for Miłosz and Brodsky’s mutual sympathy and fascination, and the ways in which they were (and remain, at least in the living word) polar opposites. The book’s fourth chapter, on “Women, Women Writers, and Muses,” stresses the differences. For the Catholic Miłosz, women were Eve, both temptation and fulfillment, while for Brodsky women were most powerfully present when already lost. Accordingly, Miłosz’s women tend to be physically real and mortal, Brodsky’s absent, imaginary, and, as in the cases of the poets Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva, figures who in his eyes were so great as to lie beyond gender. It is striking that, despite the tribute both pay to women as intellectual forces and influences, neither Miłosz nor Brodsky seems able to conceive of a woman at once erotically and in the fullness of her intellectual powers. Miłosz’s “What I Learned from Jeanne Hersch” concerns a Jewish philosopher and his sometime lover, who appears in the poem only as the source of twelve numbered lessons, such as: “11. That time excludes and sentences to oblivion only those works of our hands and minds which prove worthless in raising up, century after century, the huge edifice of civilization.” Grudzinska Gross suggests that, if there has to be an “amputation” of head from body in a poetic portrayal of a woman, Miłosz’s choice to give us Hersch’s head is preferable.

The overwhelmingly masculine tone of Russian and Polish letters often belittles concerns about women, mistaking them for manifestations of a narrowly programmatic feminism that must be deflected. But, to a growing group of readers, Miłosz and Brodsky’s representations—or, rather, their abstractions—of women make them seem dated. Women writers such as Magdalena Tulli and Polina Barskova, and scholars including Agata Bielik-Robson and Grudzinska Gross herself, are doing much to enliven the Slavonic-American literary and intellectual scene. At the same time, a whole new generation of Eastern and Central European poets is learning the joys of montage rather than amputation. With any luck this generation’s readings of Miłosz and Brodsky will gradually filter through to the United States, complicating the hagiographical tenor of most discussions of the two.

That hagiography is the dominant idiom is remarkable in itself. Miłosz and Brodsky achieved their prominence in American letters in the 1970s and ’80s, rejecting the various strains of post-structuralist theory that held sway in humanities departments. Fresh from the toxic laboratory of the Communist experiment, they had no use for an intellectual and aesthetic framework built largely on Marxist ideas.

Yet Brodsky and Miłosz created for themselves a place in American literature: a heartening proof of the independence of poetry from theory (as distinct from ideas). For no matter what one thinks of this or that pronouncement or rhyme by Miłosz or Brodsky—and one does at times weary of great-poet pronouncements, the intellectual equivalent of forced rhymes—reading their work against Grudzinska Gross’s eloquent account of their struggles cannot help but foster gratitude for the extraordinary intensity and scope of their minds, and above all for the sheer ambition and energy with which they brought their inimitable and irreplaceable voices into the world.