Adam Fitzgerald: Why don’t you start by talking to me about your relationship to light verse. Like many eighties babies, I suspect, the first verse I ever had waffled into my ears was Shel Silverstein. His “Sick” was a favorite poem for many time-units I can’t quite call years because I’m sure they were less sustained in attention but felt infinitely longer than that, retrospectively: “I cannot go to school today,” / Said little Peggy Ann McKay. Somehow this listicle poem with its obsessive body imagery has lodged itself in me to such a degree I can’t entirely rid myself of seeing its influence, precious as it sounds. I'm wondering what poems, early or late, in a tradition of silly, nonsensical or light verse have clung to you—and how you relate to that critical distinction as a category of poetry in general.

Anthony Madrid: I didn’t love children’s poetry when I was a child. I started getting off on it when I was around thirty. I do remember I always experienced some kind of murky satisfaction from anapests, but that feeling definitely does not deserve the name “love.” Children’s poetry didn't “speak to my concerns” when I was a child. Only now does it answer my needs. As for calling this stuff “light verse” or “nonsense verse,” I don’t love that. But I don’t know what to call it instead.

AF: Why do you resist calling it light or nonsense verse? Those are pretty established critical terms, no? Does Auden’s famous revisionary anthology, W. H. Auden’s Book of Light Verse, mean anything to you?

AM: The terms “light verse” and “nonsense verse” make the stuff seem more anodyne than it is. The things I love sometimes have real power. I admit that plenty of what people call “light” really is light, but what do you do with something that is 80 percent light but has a sting in its tail? Auden’s anthology is a beautiful book. I used to know it well. But Auden’s definition of “light verse" isn’t very convincing. You scan the table of contents and say again and again: “This is light verse?” Lots of black magic in there.

AF:Talk to me about the writers in this tradition that interest you and how you got into it around thirty.

AM: I was in Tucson. Somehow I got a hold of Holbrook Jackson’s edition of Edward Lear, and I read certain things over and over. I thought: This guy’s got the touch. “How Pleasant to Know Mr. Lear,” “The Owl and the Pussycat,” “Mr and Mrs Discobbolos”—so much pleasure. I didn’t look at the limericks. In Tucson, I started the Swallow-a-Library Project, which involved reading Shakespeare and the Bible and the Norton Anthology of Poetry, floor to ceiling. I read hard. I found Auden’s “Miss Gee.” Walter de la Mare’s children’s poetry. Certain things by Emily Dickinson. I was catching the rhyme disease. One key point. Loving children’s poetry or anything that was an “easy read” had this special satisfaction: I knew I was authentically loving it, because nobody was gonna gimme any credit for doing so. There are a lot of reasons besides Milton to love Milton; proves you’re smart. But if you love Edward Lear, at least in my milieu, you simply love him. He’s all yours.

AF: So tell me about what draws you to the limerick and how this project came about in particular, including your collaboration with artist Mark Fletcher.

AM: Limericks. OK, at first, I thought I loved all limericks. That was very wrong. I don’t like clever ones. Or rarely. Sexual ones either. Those are almost never any good. I like boneheaded ones. To me, this is a really, really good one:

There was an old man of Boulak,Who rode on a crocodile’s back.But they said, “Towards the night he may probably bite,Which might vex you, old man of Boulak!”

The very word “Boulak,” and the way your lips have to go flabble plap as you say “he may probably bite,” and calling the guy “old man of Boulak” as if that’s his name, and just the nutty logic that says the crocodile will eventually get cranky as the day wears on—these things make this an A#1 limerick, to me. Edward Lear wrote it, 19 March 1867. He wasn’t a wit; he was perverse and humorous.

Now, when I started making limericks, all I wanted was for there to be more of him. I knew there needed to be drawings, and that mine would never do. Then I thought of Mark Fletcher, who had done the cover for my book of poems in 2012. It was an electrifying moment. I believed then and still believe there is no other living person better suited to the task of illustrating these things. I’ve never met him, even to this day, nor heard his voice. I didn’t even know what he looked like until B O D Y published a photo of him alongside the first round of our collaborations. My entire relationship with that inspired artificer is founded on a tiny thread of crazy-brief e-mails. . .

AF: Incredible! Finally, what else are you working on now?

AM: Ah. I have this set of poems based on a medieval Welsh form that I’m in love with. It would take too long to explain. The main thing is they’re super repetitive, and each stanza ends with a short bold axiom. Lot of salt. For anyone who’s thinking “Hmm, that sounds like my kind of thing,” I can recommend a beautiful and fairly unknown book: Studies in Early Celtic Nature Poetry, Kenneth Jackson, Cambridge 1935. Basically my Bible, these last eighteen months. My only warning is that if you read this book, you will helplessly fall under its spell and start writing like that.

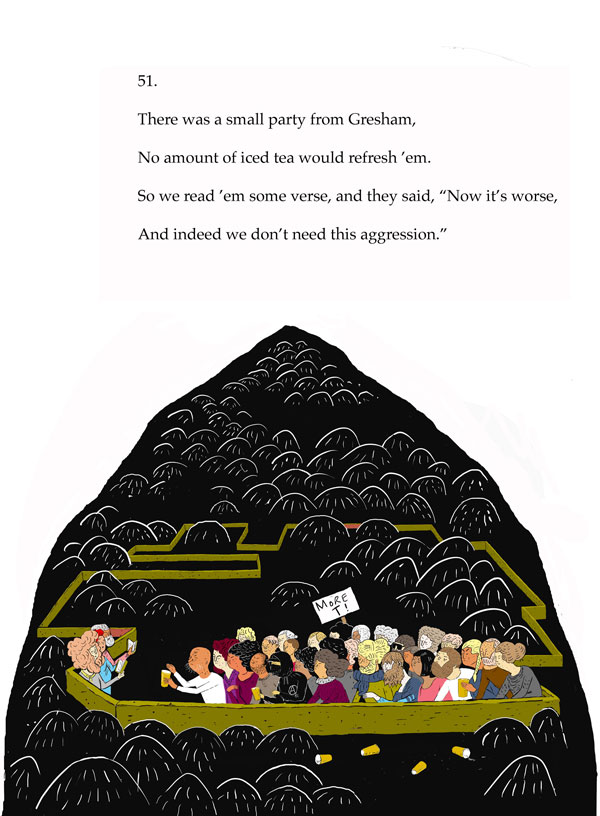

Limerick No. 51

Limerick No. 51

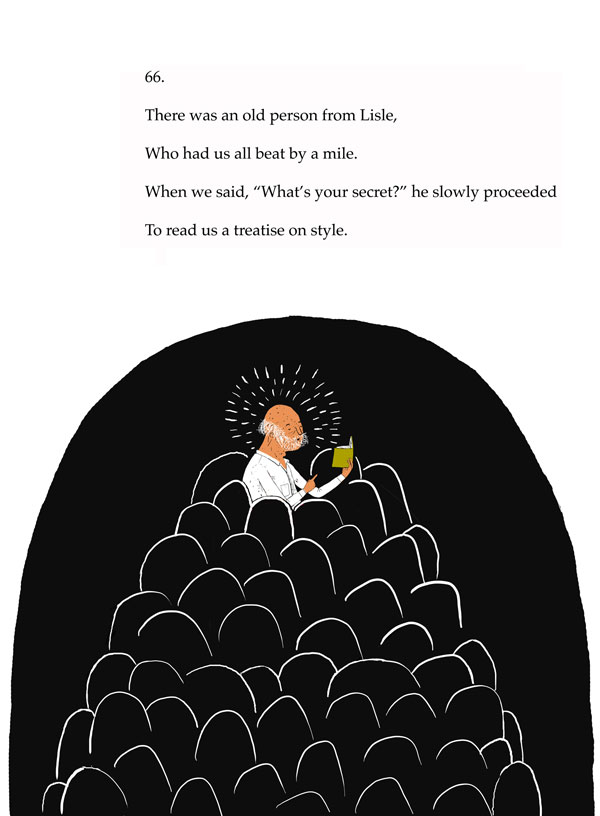

Limerick No. 66

Limerick No. 66

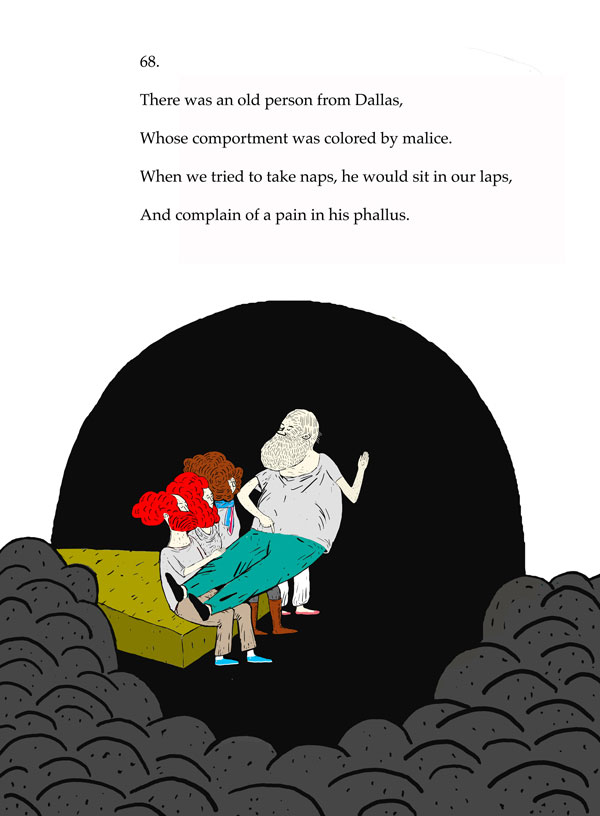

Limerick No. 68

Limerick No. 68

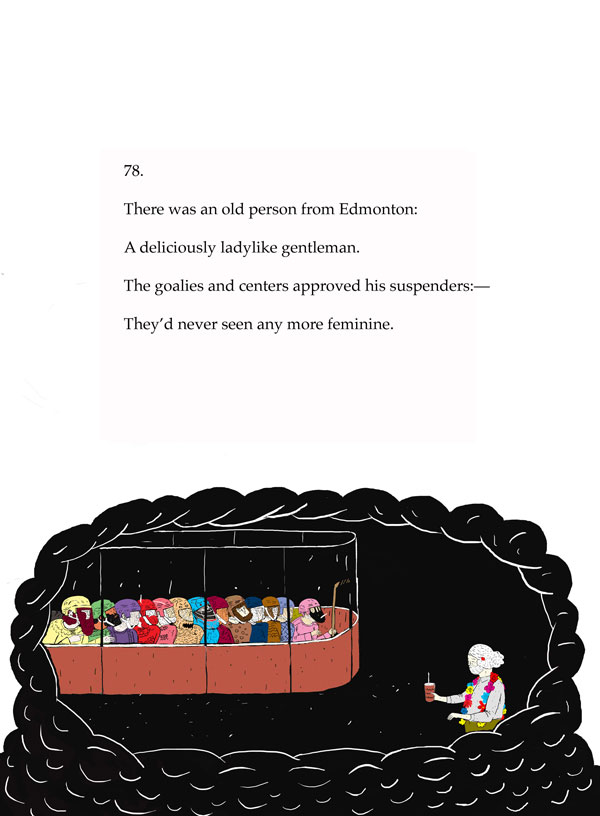

Limerick No. 78

Limerick No. 78

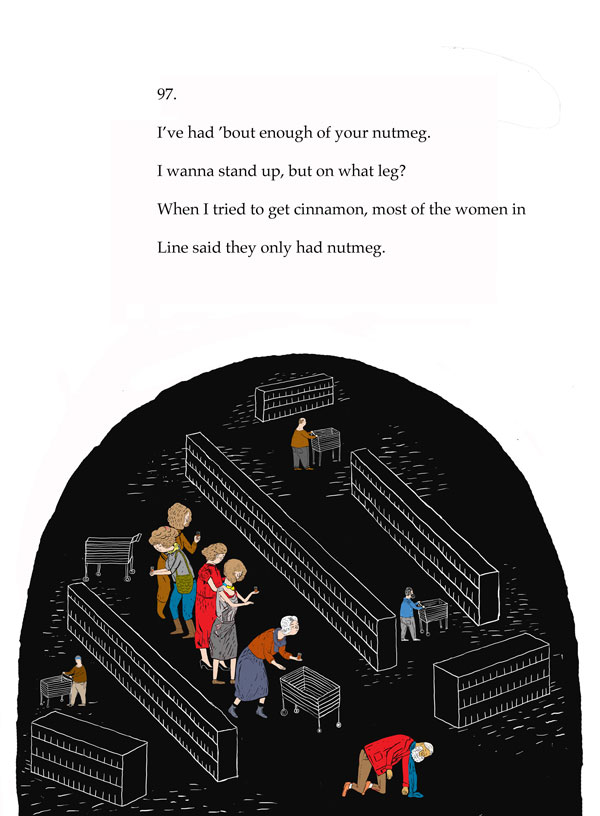

Limerick No. 97

Limerick No. 97