Purchase this issue here, or become a member and get it as your first issue.

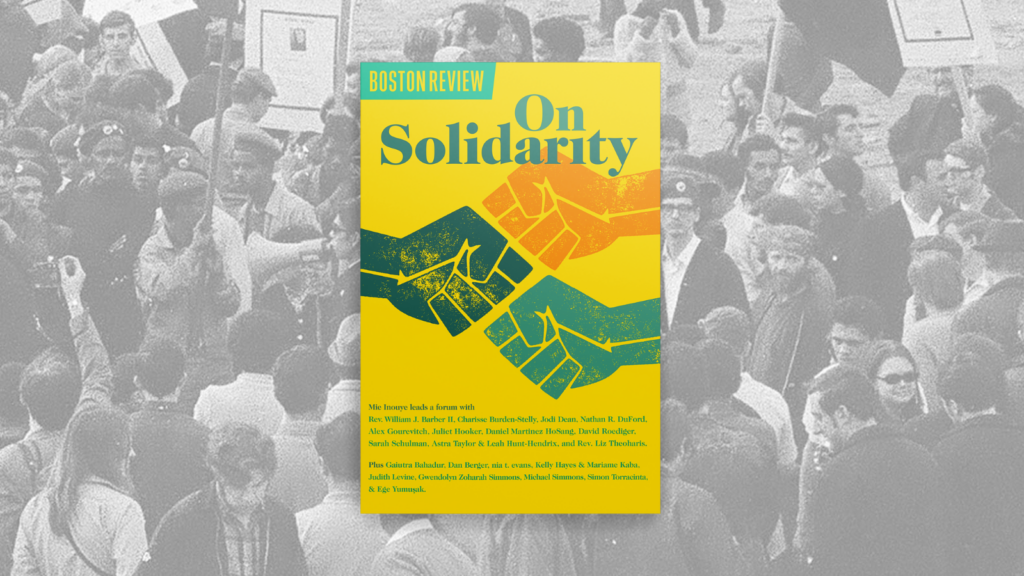

Solidarity has long been a key idea in struggles for a more just world. What does it mean, and how can movements build enough of it to change society?

Organizer and political theorist Mie Inouye leads this issue’s forum on obstacles to collective action today. “Even though we recently experienced one of the most remarkable displays of interracial solidarity in our country’s history,” she writes of the protests following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, “interracial solidarity—solidarity across any form of difference, for that matter—seems less plausible now.” In the years since, debates about the role of race and class in movement spaces have suggested a cruel paradox: “On the one hand, solidarity is an essential component of struggles for justice, but on the other hand, actually existing injustice renders it impossible.”

In the face of this impasse, movements have frequently turned to deference politics—a model of coalition building that asks relatively more privileged people to defer to the most marginalized. Inouye argues that this vision has made movements brittle. In place of deference, she proposes a model of organizing that embraces conflict as a form of political education and personal transformation—all in the interest of building endurance, which is key to making change. And for that, Inouye concludes, there is no substitute for the hard work of good organizing.

Eleven respondents pick up different threads of Inouye’s argument. David Roediger and Sarah Schulman expand on the “antinomies” and “dilemmas” that can make solidarity so fraught. Daniel Martinez HoSang traces the cause back to neoliberalism, which splinters social relations and teaches us to express injustice in the language of personal grievance. Alex Gourevitch sees the debate as a “cipher for the problem of trust.” And in different ways, Charisse Burden-Stelly, Jodi Dean, and Rev. William Barber II clarify the political stakes of social movements. In her reply, Inouye stresses how the social and political are intertwined.

Other contributors explore solidarity in specific contexts. Labor organizer Ege Yumuşak makes the case for more democracy in unions. Gaiutra Bahadur rejects the Asian exceptionalism that has obstructed multiracial solidarity. In conversation with nia t. evans, Dan Berger, Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, and Michael Simmons reflect on the lessons of the civil rights movement and beyond. Reviewing films about abortion, Judith Levine teases out the solidarity that emerges as reproductive rights narrow, while Simon Torracinta shows how basic income can pave the way to a more solidaristic society. Finally, veteran activists Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba share what they have learned about keeping people moving toward the same goal.

Together these pieces offer a window into how social change happens. Solidarity is important, they make clear, because it is essential to movements—and movements are essential to building a more just world. As Astra Taylor and Leah Hunt-Hendrix put it, “Without solidarity, we’ll remain divided, which means we’re already conquered.”

We’re interested in what you think. Submit a letter to the editors at letters@bostonreview.net. Boston Review is nonprofit, paywall-free, and reader-funded. To support work like this, please donate here.