It was during a family trip to Greece that Boyan Slat first encountered the problem of plastic marine pollution. While scuba diving off the Mediterranean coast, the sixteen-year-old Dutch inventor was surprised to find more plastic bags than fish populating the sea, a sight made more unsettling for him by how closely the bags resembled jellyfish when submerged underwater. Thus began Slat’s obsession with plastic waste, an obsession that eventually culminated in the creation of The Ocean Cleanup, arguably the first foundation of its kind to blend environmentalism with the “disruptive” logic of Silicon Valley.

Emerging out of the buzz generated by a single YouTube video, The Ocean Cleanup is perhaps the first foundation to blend environmentalism with the ‘disruptive’ logic of Silicon Valley.

According to recent scientific research, the amount of plastic in the world’s oceans will outnumber fish by 2050. On the flipside, efforts to clean up the oceans have been unable to match the scale of the problem. They have typically relied on ships equipped with nets to traverse the oceans and proactively collect plastic—a strategy that could take hundreds of years and cost tens of billions of dollars while simultaneously causing further environmental damage. When Boyan Slat returned home from Greece, he began researching alternative solutions to the problem of plastic marine waste. It started as a homespun science project, but in less than a year Slat had developed a prototype that would go on to win awards and garner international attention. Slat’s innovative solution was to let the oceans do the work, as he describes in his TEDx talk titled “How the Oceans Can Clean Themselves.” Departing from past methods, his design expedited the retrieval of plastic by capitalizing on the flow of ocean currents. Slat’s vision called for thousands of floating barriers to be deployed across the most polluted waters, each barrier acting as an artificial coastline that passively receives plastic rather than chasing after it.

Like many crowdfunding efforts, Slat’s TEDx video lingered online for weeks, then months, apparently doomed to obscurity. Then, one day in March 2013, the clip unexpectedly went viral across social media, raising $80,000 in 15 days and eventually generating upwards of $2 million in funding from 38,000 donors over the following year. The money provided a seed round for Slat’s new foundation, The Ocean Cleanup, which soon hired over sixty employees to help turn his prototype into reality. Roughly three years after his fateful trip to Greece, Slat was presiding over a large-scale environmental startup—one that continues today. It is perhaps the first of its kind to emerge out of the buzz generated by a single YouTube video.

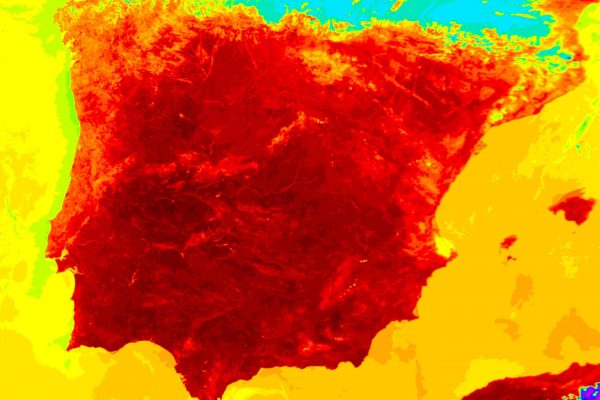

The Ocean Cleanup brings a welcome sense of optimism to an issue that has long felt insurmountable. Public awareness about plastic waste in the oceans dates back to the eighties, when researchers first noted high concentrations of debris in the North Pacific Ocean, a smog-like cloud of particles later named—somewhat misleadingly—the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP). In the years that followed, a steady stream of scientific studies, news reports, and photographic footage revealed the catastrophic scale of the crisis, though measures to mitigate the problem have remained sparse. Meanwhile, the rates of plastic production and pollution are accelerating. The GPGP has today been joined by four other trash-infected gyres, or revolving ocean currents, overrun with plastic.

Slat believes that his project, and the celebrity factor it has attained, can reignite awareness and concern about the issue. He has already become a staple of glossy environmental coverage: VICE dubbed him the “The Ocean Cleanup Kid,” Forbes recognized him as a “30 Under 30 Innovator,” and the United Nations Environmental Programme anointed him as a “Champion of the Earth.” These honors were awarded before a single prototype of his venture shipped out to sea, a sign of how accustomed we have become to the narrative of a teenage prodigy single-handedly solving the world’s biggest problems. Slat’s affinity with the media recalls another high-profile inventor-entrepreneur, Elon Musk, who garners sweeping coverage for merely suggesting breakthrough ideas—most recently, the Hyperloop—before ever delivering on them.

Newly flush with capital, The Ocean Cleanup hosts events that emulate the spectacle of a Silicon Valley product launch. Slick visuals and live demos dazzle audiences while Slat translates technical insights into pithy soundbites: ‘To catch the plastic, act like the plastic.’

While some see Slat’s story as an admirable example of the entrepreneurial can-do attitude, others are not so easily persuaded. Amongst his skeptics are the scientists who have been researching the issue for decades. In an interview with Public Radio International, marine researcher and founder of the 5 Gyres Institute, Marcus Eriksen, summed up the consensus view of scientists who have been focusing their efforts on prevention: “I’m sorry to say it, but I think these downstream mitigations out in the middle of the ocean are a distraction from the work that almost all environmental organizations are focused on.”

Simple math reinforces Eriksen’s point: The Ocean Cleanup’s moonshot goal of eradicating the GPGP within five years would successfully remove nearly 200,000 tons of plastic from the ocean, but in that same time period an additional 50 million tons of new plastic waste will have more than replaced it. Even more damning is the fact that the vast majority of the nearly 13 million tons of plastic that enters the ocean each year sinks beneath the surface, beyond the reach of clean-up methods. This reality can only change through a zero-tolerance policy on pollution, which would negatively impact consumers and businesses alike. Upon closer inspection, the grand vision that Slat calls “the largest clean-up in history” is a quite modest proposal, addressing only a sliver of the larger problem.

Despite these criticisms from the environmental community, it is the narrative around technology and innovation that holds value in the marketplace, and Slat continues to be rewarded handsomely. Following an announcement earlier this year that a series of design tweaks could double the efficiency, or capture rates, of his floating barriers, The Ocean Cleanup secured a more lucrative second round of funding, raising over $30 million from institutional investors such as Peter Thiel, the co-founder of PayPal, Marc Benioff, the CEO of Salesforce, and multinational corporations such as Royal DSM and AkzoNobel. Newly flush with venture capital, The Ocean Cleanup’s latest public events increasingly resemble the spectacle of a Silicon Valley product announcement. Large-scale visuals, minimalist slideshows, and live demos dazzle audiences of tech reporters and devoted fans, while Slat translates technical insights into pithy, counterintuitive soundbites. “Why go after the plastic if the plastic can come to you?” he asks, referring to the epiphany underlying his original design. “To catch the plastic, act like the plastic.”

But Slat’s new coterie of returns-hungry investors may also be compromising his vision in more substantive ways. Over the summer, The Ocean Cleanup revealed a new aspect of its long-term business strategy: branding opportunities for companies such as Apple or Microsoft to sponsor individual booms and monitor live data on how much plastic they are collecting, an idea that sounds less like a revolutionary environmental project and more like the stuff of satire. “It’s almost like a gamification of cleaning the ocean,” Slat says when describing the initiative.

Upon closer inspection, the grand vision that Slat calls ‘the largest clean-up in history’ is a quite modest proposal, addressing only a sliver of our larger plastic problem.

Meanwhile The Ocean Cleanup carries on with the premise that eliminating these symbolic patches of garbage from the ocean is the most pressing way to spend upwards of $30 million. Missing from its elaborate presentations and from Slat’s numerous press interviews is any serious challenge to our throwaway culture or to our continued inability to prioritize public goods over free-market ideology. This unspoken reality might explain why uber-industrialists such as Thiel and even petrochemical conglomerates such as DSM are publicly supporting the project—a feel-good effort that in many ways reinforces the status quo.

Activists such as Eriksen aren’t so much concerned that The Ocean Cleanup will under-deliver as they are about its potential to divert attention away from more fundamental issues. Of all the pollutants that enter our oceans legally each year—a list that includes agricultural fertilizer runoff, flushed pharmaceuticals, oil spillage, and untreated sewage—plastic has proven to be the most insidious. The smooth polymer that has made modern lifestyles safer, cleaner, and more convenient than ever is also by design indestructible, wreaking havoc on natural ecosystems after it has been discarded as waste. The items we throw away not only wash up on the shores of uninhabited islands and accumulate in the far-reaches of the Arctic Ocean, they return to us in unexpected places, including our dinner plates as marine wildlife increasingly mistake plastic particles for food.

In many ways plastic waste is a more uncomfortable issue than even the now-controversial threat of climate change, precisely because it implicates so many facets of how we live. The vast majority of the plastic in or around the oceans comes from single-use plastic goods—those innocuous consumer items such as bags, straws, bottle caps, and toothbrushes that pass through our hands multiple times everyday. While the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy primarily involves a boardroom-level reshuffling of capital and resources, banning the use of disposable plastics would immediately undermine many of our daily conveniences and make the idea a political nonstarter.

Framing the problem in financial terms and metrics of profit and loss can distract us from a more fundamental question: why should clean oceans have to make good business sense?

The lack of urgency around the issue has been on full display at the United Nations over the past year. The Paris Climate Agreement, signed by nearly 200 countries, was heralded as a landmark achievement in the fight to curb carbon emissions, but it never once mentioned the words “waste” or “plastic.” When the UN hosted its first-ever Ocean Conference this past May and proposed a Paris-like agreement to phase out single-use plastic goods, a mere ten countries signed the agreement. Recently, in an effort to underscore how little has been done to address the problem, activists from the Plastic Oceans Foundation petitioned the UN to recognize the GPGP as its own sovereign country, the “Trash Isles,” with Al Gore signed on as its first citizen and a proposed currency called “debris.”

Filling the void left by policymakers are a host of these kinds of NGOs, non-profits, foundations, and private companies that, for a variety of reasons, have taken up the issue of plastic waste as a cause célèbre. They deploy guerilla tactics in a bid to generate publicity, as in the case of the “Trash Isles.” They organize annual grassroots coastal clean-ups and protest the use of particularly egregious plastic consumer items, such as the microbeads commonly found in beauty and hygiene products (which Obama banned in 2015). Such efforts, and the occasional victories they inspire, may help limit the extent of the damage, but they pale in comparison to the macroeconomic forces that will see our annual plastic dump rates double over the next twenty years.

With a lack of attention or funding from policymakers, many “clean ocean” initiatives must also increasingly address the plastic waste problem on the terms of their corporate or private donors, as evidenced most vividly by The Ocean Cleanup’s latest branding initiatives. Metrics displayed prominently on environmental websites often boast about cost savings, value-adds, and increased consumer goodwill. At times this data reflects meaningful improvements in efficiency or impact. But by viewing the problem through financial terms, these metrics, and the pseudo-industry they support, also distract from a more fundamental question: why should clean oceans have to make good business sense?

The only true solution to our plastic waste problem is simple, obvious, but so radical that it almost seems naïve. Any promise for a sustainable future requires a ban on the manufacture of all material not 100 percent recyclable or biodegradable. This model is often described as a “circular economy,” one in which industrial activities are “restorative and regenerative by design” (as defined by British sailor and marine activist Ellen MacArthur). A similar logic underlies designer William McDonough’s 2002 sustainability manifesto Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, which calls for the end of the linear, single-use “cradle to grave” mindset that propelled mass consumerism throughout the twentieth century. Since every object we create will inevitably one day lose its vitality, transforming instantaneously from “asset” to “waste,” a circular economy mandates that every material contained therein ought to be capable of nourishing something new, whether biological or industrial. The plastic handlebar of a toothbrush, for example, can be melted down into raw industrial material, while bristles made of organic matter can be returned to the soil as food for plants.

Circular economies are the ideal iteration of any true recycling effort, as most conventional processes can more accurately be described as “downcycling,” reusing material from one disposable product to create another. Downcycling does not eliminate the problem of waste. It merely delays it by a generation, and that process itself can consume as much energy and generate as much waste as making a new product from raw materials. When Terracycle—an environmental startup founded by another boy visionary—sells branded messenger bags made out of recycled Capri Sun pouches, there is an illusion of sustainability. But what is missing is any discussion of the resources required to create the new bag or where it will inevitably end up.

In a move that sounds less like a revolutionary environmental project and more like the stuff of satire, companies such as Apple and Microsoft can sponsor and brand individual booms and monitor live data on how much plastic they collect.

Recycling must ultimately play a role in any waste-free future, but these efforts are not always as feasible or fruitful as one may expect. Three and a half billion humans still have no basic access to waste disposal or removal services, and the world’s fastest growing markets for consumer plastics are the same countries whose governments have not yet developed sufficient waste management systems for their ballooning populations. Even in developed countries, recycling rates can be as low as 10 percent for plastic goods, signaling a lack of priority or urgency, an inconvenience that modern consumers may not be willing to afford or endure. The stakeholders that too often go unaddressed in these conversations are the commercial interests who manufacture and sell the plastic in the first place, but whose PR departments have been wildly successful in passing on the indirect costs of waste management to public stakeholders.

In her review of Eriksen’s book, Rachel Riederer notes how industry-funded organizations such as Keep America Beautiful have subtly shifted the blame for plastic pollution away from manufacturers and towards consumers and municipalities. The iconic (and deeply racist) “Crying Indian” advertisement from the seventies, for example, features a “Chief Iron Eyes Cody” character who is apparently more upset by bags of potato chips being thrown from car windows than he is by the monstrosity of the interstate or the sullied urban landscape. Even today’s most progressive companies typically evade the question of where their products go when they are no longer wanted. Green-friendly packaging often promotes the sustainability of input materials (for instance “100 percent post-consumer recycled material”) with little discussion of the products’ post-use sustainability.

In some parts of the world, the tide may finally be turning. Governments across Europe and southeast Asia are implementing more aggressive extended-producer responsibility (EPR) laws, which pass the costs of recycling goods back onto manufacturers, incentivizing companies to use less packaging and create longer-lasting products. These laws finally align private and public interests, sparking creative solutions as well as simple ones. In Germany, for example, the first country to enact a federal EPR law back in the early nineties, plastic toothpaste tubes stand naked on the shelves, free from the superfluous cocoon of paper boxes and clear plastic wrap that consumers crumple up and throw away immediately after buying.

Following the discovery of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in the late eighties, many environmental activists were surprised at the lack of public response to the crisis. Writing for the New York Times in a 1992 article titled “The World’s Oceans Are Sending an S.O.S.,” journalist Michael Spector observed that: “There may be a hole in the ozone and acid rain falling on the forests, but surely the oceans—the ineffably endless oceans—will always be there to wash away the accumulated grime of lives tethered to the land.” The resilience of our collective delusion shouldn’t be surprising. As recently as the seventies, it was perfectly legal and common for U.S. companies to discard their plastic, medical, or even radioactive waste directly into the ocean, a devastation that continues in many places today. In his book, Waste: An Object Lesson (2015), Brian Thill recalls how nineteenth-century urban planners explicitly designed cities such as Chicago under the assumption that nearby bodies of water could absorb the city’s rubbish and sewage in perpetuity.

Our reflexive, at times mystical, belief that the ocean can absorb our sins is not only a modern predicament, but an ancient disposition between humans and the sea. In her book The Sea Can Wash Away All Evils: Modern Marine Pollution and the Ancient Cathartic Ocean (2006), historian Kimberley Patton surveys sacred stories from multiple religions and finds a universal belief in the cleansing power of the ocean, its ability to “wash away or absorb what otherwise would be unbearable if allowed to remain on land, the normal theater of ritual life.” Ancient parables are replete with characters tossing objects, bodies, and secrets into the sea, trusting the waves will be powerful enough to bury those painful relics of the past and bring about some kind of renewal. This motif has carried across centuries of literature, art, and cinema, and no matter how many dystopian images cross our screens each day, we still subscribe to the notion that the unfathomably large and self-replenishing oceans can withstand any foolish harm that humans may inflict upon them.

Plastic waste is a systemic problem, a negative externality that degrades the planet but drives the global economy. It cannot be solved by thinking in purely economic terms.

But the logic underlying these stories no longer bear out in reality. We are, for the first time, facing the limits of our boundless faith in the sea. Objects we dispose of in the most distant expanses of ocean are washing back up on our shores. Patton’s book, published a decade ago, is framed as a kind of elegy to this majestic relationship between man and ocean. She writes: “We [now] confront the nondissolving, ugly reminders of what we had discarded, the consequence of our ascription of an instrumental rather than an intrinsic value to the sea.” The symbolic role of our oceans has transformed from spiritual salve to unflinching mirror, reflecting back to us the full and inevitable consequence of our self-destructive habits and self-created crises.

Perhaps this can serve as a reminder that plastic waste—like any form of marine pollution and like the mother-of-all issues that is climate change—is a systemic problem, a negative externality that degrades the planet but drives the global economy. It cannot be solved by thinking in purely economic terms, and strategies of assigning financial value might in fact perpetuate the same issues as the logic of minimizing costs is merely rewritten in more palatable ways.

Ridding the oceans of plastic and other hazardous pollutants is a necessary first step in any plan to save our planet and, by extension, ourselves. If Slat’s team at The Ocean Cleanup succeeds in building a scalable prototype, maybe that cleansing will happen sooner rather than later, sometime this century rather than the next. But these efforts will only matter if we can simultaneously change the model that favors economic growth over ecological health. Until the latter becomes a prerequisite to the former, the battle will continue on the high seas as private actors, motivated by concrete incentives, continue to find legal ways to fill the oceans, rivers, coastlines, and reefs with their alien byproducts.