Complete Poems

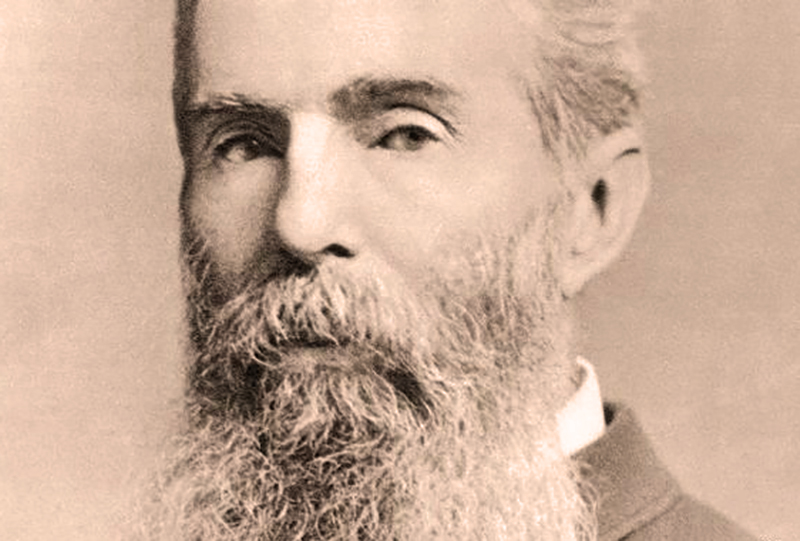

Herman Melville (ed. Hershel Parker)

Library of America, $45 (cloth)

The Library of America edition of Herman Melville’s Complete Poems collects, for the first time, all of Melville’s known poetry. This includes collections published during his lifetime and reviewed widely, such as Battle-Pieces (1866), completed in the aftermath of the Civil War. In addition, the book collects work largely unknown by—and unavailable to—general readers until now. This latter category includes the epic poem Clarel (1876), notable both for being the longest American poem to date, and for having most of its first edition burned by the publisher to clear out warehouse space. Library of America is billing the Complete Poems as a resuscitation of one of the United States’ greatest nineteenth-century poets, establishing Melville within the company of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. But while the collection has the potential to change popular understanding of the kind of writer Melville was, the pleasures of reading Melville as a poet are ambiguous, as is the urge to classify him as great.

Almost all of Melville’s fiction was, in some sense, autofiction, and this idea of literature crafted not out of fantasy but of the stuff of life is a useful lens through which to view the bulk of his poems, too.

In a prose sketch, “House of the Tragic Poet,” written sometime during the last three decades of his life, Melville imagines a friendly editor’s advice to an aging poet seeking publication for a collection combining poetry and prose: “as regards your manuscript,” the editor confides, “the originality, let me frankly say, is mostly of the negative kind.” Melville wouldn’t have had to stretch far to anticipate such criticism. As a fiction writer, his career tanked after certain demonstrations of originality: in 1851 with the publication of Moby Dick—widely panned upon publication—and even more so the following year, when he published Pierre, an allegorical romance turned urban thriller with heavy doses of incest, gypsy guitars, and aesthetic theory, the combination of which the nineteenth-century reading public was decidedly underprepared to receive.

If it is possible to read Melville’s earlier fiction as “a quarrel” with the forms of fiction itself, as critic Nina Baym memorably suggested—a Bartlebian “I would prefer not to” to the expectations of plot and character—then that difficulty translates to Melville’s poetry as well: he is neither an easeful poet nor an easy one. Many of his poems adhere to rhyme and meter far more rigidly than Whitman’s or Dickinson’s do, in ways that will sound tinny and outmoded to a contemporary reader’s ear. Yet his lyrics, like Dickinson’s, reward deep inspection. And they can be as jocular and inviting as Whitman’s constant come-ons, though more obliquely so.

Melville’s poems are also keenly aware of themselves as language in a way that both Dickinson and Whitman eschew in their pursuit of Romantic naturalism. If Whitman loafs and gropes in the grass, and Dickinson scrutinizes robins in the garden, Melville can feel stuffed up in the library, sick with over-reading. His poems can also feel like a conversation of one, a quality a contemporary of Melville’s, John Stuart Mill, argued was the hallmark of lyric poetry: private language, overheard.

Melville’s poems are keenly aware of themselves as language in a way that both Dickinson and Whitman eschewed in their pursuit of Romantic naturalism.

At the same time, however, his poems blast apart the notion of lyric poetry as shut off, in some precious, dusty corner, from real life. In recent decades, scholars have argued against receiving Dickinson’s and Whitman’s works in this way. Their poems aren’t pristine artifacts, the argument goes; they’re shaped by context, historical and material. As fascinating as Dickinson’s poems scrawled along envelope flaps are, however, there’s a reason Dickinson defined poetry as the feeling of one’s head flying off (her poems can make your own head feel that way) and that Ralph Waldo Emerson recognized something entirely new in Whitman’s sprawling, democratic lines. They stand up in anthologies. They beckon on their own. But even at their most conventional, most of Melville’s poems never escape context: they are formal machines for processing experience. You can’t shake Melville out of his poems.

One of Melville’s favorite words, and ideas, in his late poetry is “afflatus”: an inspiring wind, passing and unpredictable. If that term makes you think of flatulence, there’s a reason that begins in etymology but extends beyond it. Melville viewed all writing as the by-product of living. There’s something slightly embarrassing about that notion that ties into the squeamishness with which some critics approach the contemporary spate of “autofiction” by writers such as Karl Ove Knausgaard or Sheila Heti. Almost all of Melville’s fiction was, in some sense, autofiction, and this idea of literature crafted not out of fantasy but of the stuff and refuse of life is a useful lens through which to view the bulk of his poems, too.

How and why did Melville become a poet? One thing he does share with Whitman and Dickinson is that poetry was, for him, a midlife turn. He began writing poems in the late 1850s, at the end of his thirties, after more than a decade of frenzied fiction production. Whitman was a journalist, and a novelist, before he tried his hand at verse. Dickinson wrote letters and likely poems from a very young age, but hit a different stride in her mid-thirties, writing many of her best-known poems around 1862 and 1863.

When he first turned seriously to poetry, Melville was no longer the well-known author of Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846) and Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847), the wildly popular adventure novels that had made him a household name, and which he had based on his experiences as a sailor (and deserter) in the Marquesas. Nor was he the expansive novelist of Moby Dick, or of the less-well-known novel he had published two years before, Mardi. In many ways, though, Melville’s development as a poet begins in that bulky novel, which, like Moby Dick, sets off as a swashbuckling buddy story, before taking a serious nosedive into uncharted waters of island-hopping and allegory. Mardi is peppered with poems: with riddling songs about the language of flowers, delivered by native priestesses paddling canoes; and with jokey, philosophical asides by the first of what becomes a string of poet-surrogates. The habit established here of treating poets as tragicomic figures would persist throughout the remainder of Melville’s career.

Like Whitman and Dickinson, writing poetry was, for Melville, a midlife turn.

But poetry also suffused Melville’s prose before he started carving it into lines. You don’t need to be scouring for iambs to sense the metrical regularity of many of the most soaring lines in Moby Dick. Reading Shakespeare in the midst of writing that novel, Melville’s language began to blaze with blank verse, the most canonical metrical line in English poetry. It’s in Moby Dick, also, that Melville began to fixate on the peripheries of traditional genres, a fascination that illuminated his path to poetry. Recall that Moby Dick begins not with Ishmael’s famous invitation, but with a preface of “Extracts” written by a “sub-sub librarian,” who has sponged through the library to compile a list of every mention of whales that he can find in other books. This figure isn’t part of the novel; he isn’t the novel’s narrator; and he isn’t the author, either, though he is a persona of one. In Pierre, Melville makes the dedication a space for more authorial performance, offering a lengthy dedication of the book to a personified Mount Greylock, the mountain visible outside his window as he wrote. The tone of that dedication, like the tone of the novel that follows, is vexing: Is he invoking a divine materiality in the guise of a mountain, or ironically blasting the idea that books might be written for other humans at all?

These moments—in which Melville establishes the text he is about to deliver as already, in some ways, outside itself—are helpful context for making sense of the striking amount of prose collected alongside verse in this edition of Melville’s Complete Poems. The trappings that surround Melville’s poetry are as important as the poems themselves: elaborate dedications, introductions, disclaimers, and headers for poems or collections; the extended footnotes; the character sketches, disconnected from anything resembling character development or plot.

We see these prose outliers in the headnotes and endnotes of his first published collection of poems, Battle-Pieces. If you’ve encountered Melville’s poems in an anthology, they were likely from this collection, which includes “The Portent,” Melville’s tersely lyrical send-up of “weird” John Brown; “Shiloh,” a requiem for the monumental battle; or the many fascinating tombstone poems (“Verses Inscriptive and Memorial”) which invite reflection on how a poem is, or isn’t, an effective monument, and how wilderness tangles around civilization, grass growing out of tombs. The poems of Battle-Pieces are compelling and important. They also reveal Melville’s complex feelings about poetry, and writing more broadly, as an inspired act versus a lasting testimony.

By the time of his next poetic publication a decade later—his irregularly rhyming epic Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land, based on his travels in the Middle East—Melville’s feelings about the afterlife of poems had become more complicated. In his headnote, he presents poetry as an ongoing fermentation, which may exhale “by a natural process” some of its qualities over time, as the distance from an original impulse grows wider.

Poetry suffused Melville’s prose before he started carving it into lines. You don’t need to be scouring for iambs to sense the metrical regularity of the soaring lines of Moby Dick.

Melville spent at least four years writing Clarel and the poem wasn’t published for another two years. He would work on some of his final poetic manuscripts for decades. This time scale is vastly different from the frenetic pace of his earlier writing life, when he averaged a novel a year for almost a decade, while also publishing short fiction and giving public lectures. Maybe in later life he was busier with his day job as a customs official, a position he began a few years before he published Battle-Pieces. Or maybe the formalism of his poems slowed him down. Or maybe he entered a new mental space in the final decades of his life as an author for whom writing as a “record” became less important.

The poems I think readers will be most surprised by are these late ones: composed, revised, reordered over the last three decades of his life, when Melville maintained a solitary, rigorous writing practice, regardless of whether he had an audience. In these decades, he labored over John Marr and Other Sailors (1888) and Timoleon (1891, four months before his death), each published only in small-run editions of around twenty-five copies each, as well as the unfinished manuscripts he called Parthenope and Weeds and Wildings.

These final works most fully embody the mash-up of poetry and prose that began to appear in Melville’s work decades earlier. In fact, one of his best-known prose works, Billy Budd (published posthumously in 1924), was composed during this period, and began as a headnote for a poem, “Billy in the Darbies.” This edition makes visible the vast quantity of other textual experiments—entangling poetry and prose—that Melville worked on steadily during the final decades of his life.

If Melville as a poet doesn’t quite stand up to the achievements of Dickinson, it remains helpful to consider how both understood something about why a writer might undertake, or maintain, a literary life in the absence of recognition. Dickinson did seek publication early on in her career, but fairly swiftly abandoned the notion. “Publication — is the Auction / Of the Mind,” she wrote. In Pierre, the novel that ended Melville’s career as a celebrated novelist, he describes how there are always two books, “of which the world shall only see one, and that the bungled one.” The book the world cannot see drinks an author’s “blood; the other only demands his ink.” There are things that happen in a writing life that have nothing to do with an audience.

If Melville as a poet doesn’t quite stand up to the achievements of Dickinson, it remains helpful to consider how both understood something about why a writer might undertake, or maintain, a literary life in the absence of recognition.

In his poetry and late prose works, Melville more overtly began to shrug off authorship. “In the truest sense,” he writes in the unpublished “Preface” in Parthenope, “author am I none.” For Melville as a poet, at the end of his life, authorship didn’t mean publication or posterity, or at least not only that. Writing was a search for a kind of intimacy—a friendship with the imagined, or the dead. In “House of the Tragic Poet” in the same collection, addressing a purely hypothetical reader, he writes, “I am making a confidant of you,” and “I desire to make a friend of you, and without frankness how accomplish it?”

The pleasure of reading Melville’s poetry lies not solely in the poems themselves, but in sustaining a relationship with a writer beyond a swoony first encounter (I nearly fell out of my seat when I began reading Moby Dick) into the sometimes desperate and often darkly humorous music of a late style.

Melville’s poems are what follows after an initial romance is shattered. At the end of Moby Dick, Ishmael has survived, bobbing on a coffin. In John Marr, we meet that sailor in another guise: wizened, land-fast, Odysseus, so vividly recalling what he has lost that those “shades,” “dear to me,” are fully “present.”

The fraught, bemused tenderness I feel when reading Melville’s poems is akin to how I feel about old friends who are far away, and all the blundering choices we made (that didn’t feel quite so stupid at the time) that stuck borders or oceans or death between us. There’s an intimacy in Melville’s poetry that can surprise you, which, like the greatest intimacies, will feel familiar and impossible and strange all at once.