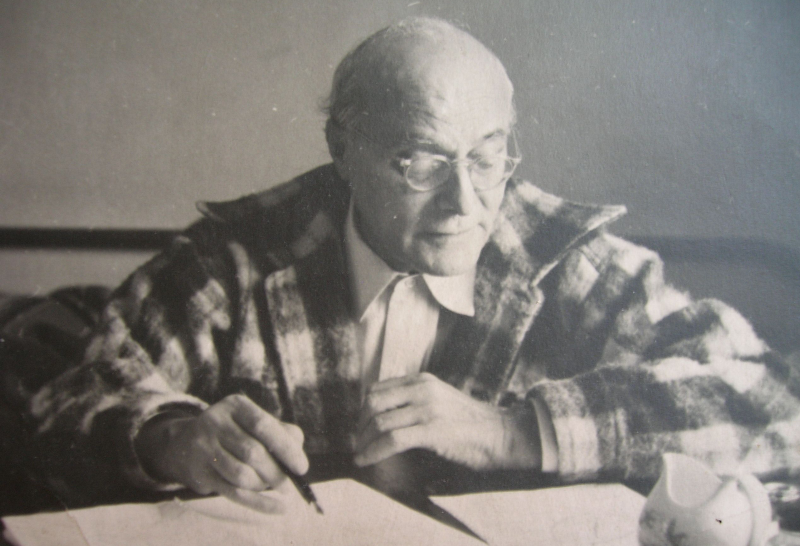

“I’m never happier,” Karl Polanyi wrote to his brother Michael, “than when I am exhausted from work, sitting in a train and, with a view of the southern English countryside outside the window, on my way home.” This was November 10, 1938, the day after Nazi paramilitaries tore through German cities smashing stores and synagogues, committing the destruction known as Kristallnacht. While racists ripped up the continent, Polanyi had taken refuge on the other side of the English Channel, eking out a living by lecturing to students of the Workers’ Educational Association. On the buses and trains of his commute to WEA sites, he puzzled over how his world darkened and sketched one of the century’s classics, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Times (1944).

Polanyi’s legacy—especially seen through that book—has been enjoying something of a comeback since 2008 thanks to the global-bashing distemper of our times. The Great Transformation is a sacred text for those who decry capitalism but shy away from the revolutionary implications of Marxism. Indeed, Polanyi—along with nineteenth-century Romantics and twentieth-century social critics such as E. P. Thompson or James C. Scott—belongs in the pantheon of thinkers that, since the dawn of capitalism, gave a vital, normative counterpoint to the hegemony of political economics, liberal or Marxist. It forged the tradition of moral economics behind a Naomi Klein, or a Bernie Sanders. But today’s Polanyi revival is not the first. The Great Transformation was also recovered in the global malaise of the 1970s. Perhaps its destiny is to be rekindled every time capitalism goes into crisis. It was, after all, conceived and written in the midst of the world’s worst cataclysm.

Polanyi’s moral economics did as much to obscure the nature of global interdependence as it did to reveal the perils of leaving the invisible hand to its own devices.

In an era of walls, visas, Eurofatigue, and slumping global trade, we turn again to moral economics for alternatives. How far can we go with them? Polanyi demanded that markets be “embedded” in wider social fabrics and serve communal purposes. The word “embedding” has since become a touchstone for market critics and sub-disciplines in the social sciences; it is a word with a career trajectory all its own. But what this actually means deserves some examination. Polanyi’s moral economics did as much to obscure the nature of global interdependence as it did to reveal the perils of leaving the invisible hand to its own devices.

Out of Hungary

Polanyi’s view of the world began in the epicenters of the Hapsburg Empire. It is one of the paradoxes of Polanyi’s life and work that he would decry the effects of nineteenth-century capitalism even as he was the heir of its sibling, cosmopolitan liberalism. Born in Vienna in 1886, he grew up in Budapest, the son of Jewish bourgeois parents who saw Judaism as a relic of shtetl or ghetto ways, a hangover from the East. The promise of the Jewish Enlightenment was this: citizenship in return for assimilation. His grandfather and father accepted the deal. Polanyi’s father, Mihály, a successful engineer, made sure that his children grew up in a capacious flat on one of Budapest’s toniest streets.

And yet the ties to Jewish circles were never completely untethered. Polanyi went to the Minta Gymnasium with a scholarship from Jewish philanthropists. His grandfather on his mother’s side was a rabbinic scholar who had translated the Talmud into Russian. Polanyi was therefore raised just outside the radius of Jewish tradition, a world he knew but could never belong to.

For the rest of his life, Polanyi searched for new communal bearings, new roots for an increasingly rootless life. As he fled Budapest for Vienna in 1919, he converted to Christianity, possibly sensing that a minority in the new national frenzy of post-1918 Central Europe was a dangerous thing to be, and that he should merge into the national Volk. Years later, in the freeze of the Cold War, he would claim that “it was the Jews that brought Christianity into the world, and this was a terrible burden. For, it brought into being the trepidation of conscience: the Jews had brought this burden into the world but then walked away from it!” They were guilty not for the death of Jesus but for “rejecting the teachings of Jesus, which are superior.”

Polanyi’s zeal to incriminate liberalism blinded him.

There is a certain parallel here between Jews in the ancient world and liberals in Polanyi’s world. One might say that he saw that in Christ’s time Jews had cleared the ground for the Christian gospel. Centuries later, liberalism had done likewise. It created the conditions for what Polanyi often called a “new Christian unity.” Just as the old Christian unity stood on the shoulders of Judaism, according to Polanyi the new Christian unity was climbing on the shoulders of liberalism. What that emerging unity lacked, however, was an understanding of itself, a narrative to replace what he regarded as a wasteland of market integration and individualism. Christianity gave him an ethical vocabulary that at once lambasted liberalism while adopting its universalism.

Meanwhile anti-Semitism destroyed the hearth of Central European assimilation dreams. It drove Polanyi into exile; it took away parts of his family. As Gareth Dale notes in his illuminating biography, Karl Polanyi: A Life on the Left (2016), the Jewish Question was a seam of unresolved issues. The moral economist hovered between his collapsing old worlds—the Jewish and the liberal—and his struggles to find a source of light for a new world.

Red Vienna

Marxism was a potential resort. It appealed to many who considered liberalism responsible for the bloodshed of World War I and, on its heels, the fascist blight. Polanyi would have an ambiguous relationship to Marxism, however. Its collectivism was a draw, but its underlying materialism was not. Polanyi never subscribed to the Second International’s orthodoxy. He helped found the Hungarian Radical Party before World War I sent him to the Russian front as a cavalry officer. Wounded, he convalesced in Budapest when Mihály Károlyi launched the First Hungarian People’s Republic. For a few furtive months in early 1919, Polanyi was close to power—as close as he would ever get. It ended with Béla Kun’s Soviet takeover; the republic turned a crimson shade of red.

The Hungarian Soviet Republic was a debacle. Appalled at what he regarded as the naïveté of the revolutionaries who thought they could create utopias out of abstract ideas, Polanyi left for Vienna to become a journalist, starting a life as the wandering un-Jewish Hungarian. The Austrian capital was home to a remarkable experiment in municipal socialism, with public housing, kindergartens, and public recreation for all. Here was a feasible model for solidarity, a secular heir to Christian unity. It failed. With some justification, Polanyi would accuse unrepentant “economic liberals” for having forced Red Vienna to its knees before the false altar of austerity. In a fascinating and little-remarked appendix to chapter seven of The Great Transformation, Polanyi likened the destruction of Red Vienna to the liberal reforms of the nineteenth century, which had destroyed the Christian charity of England’s poor laws. Neither the community of the squire’s village nor working-class Vienna could withstand “the iron broom of the classical economists.”

The experience was enough to poison for good his view of bankers. He spared choice words for the privileged role of haute finance in the spoils of the nineteenth century and the cynical way in which money men rebuilt the hollowed order after 1919 by spreading suffering among the have-nots. By the 1920s, Polanyi writes, “currency had become the pivot of national politics. Under a modern money economy nobody could fail to experience daily the shrinking or expanding of the financial yardstick; populations become currency-conscious.” The cult of stable money concealed a basic truth: it depended on forces outside national boundaries, beyond the reach of community regulators. There are times when one can almost feel Polanyi reaching for clichés about conspiracies of rootless cosmopolitans. Meanwhile, turmoil “shattered also the naïve concept of financial sovereignty in an interdependent economy.” The solution was to double down on the gold standard and all but ensure its eventual collapse.

His obsession with liberal failures and his blind spot for reactionary nationalism would only grow with time.

That crash came in 1929, and brought down the frail liberal consensus that filled the void after 1919. Eventually the reactionary tide that swept Hungary and Germany closed in on Austria. In late 1933, Polanyi, a socialist without a party, left for England. It is revealing that Polanyi blamed liberals for the collapse. The fact that Vienna was a cosmopolitan city surrounded by conservative resentment and clerical zeal to clamp down on urbane modernists did not figure into his story. This obsession with liberal failures and his blind spot for reactionary nationalism would only grow with time.

By now some of Polanyi’s traits had come clear. First, he would not embrace Marxism, Zionism, nationalism, liberalism, conservativism—all the traditional -isms that defined the ideological wars of the century. Second, as Dale notes perceptively, Polanyi was inclined to think in polar extremes. Only when it came to politics did he veer toward the reforming middle. He would spend his life searching for the near-impossible: a non-liberal middle ground.

Polanyi’s ethos finally took shape while in exile in England. There he brushed with Christian and guild socialism, which inherited English romantic notions of craftsman autonomy and artisanal disdain for wage labor and pushed them into schemes of state ownership and guild management of manufacturing. Their chief proponents, R. H. Tawney and G. D. H. Cole, left a deep imprint on The Great Transformation. Both were sworn to a non-materialist code. Along with Harold Laski, they were giants of the interwar British left. Like Polanyi, they were ethical stepchildren of nineteenth-century liberalism, quick to condemn its shortfalls and determined to create a new moral order without the odor of Marxist class conflict. Theirs was a generally optimistic view that saw the breakdowns of the 1930s as growing pains in the march toward communities of unselfish producers sharing their wealth as an alternative to market capitalism. Polanyi, who had met them during an earlier visit, admired their fusion of socialism with Anglo-Saxon liberty, religious tolerance, and “general humanitarian outlook.” Tawney and Cole were also believers in adult education and figures behind the WEA, which employed Polanyi as an itinerant lecturer.

Polanyi, however, was more bitter about liberalism than Cole or Tawney. Whereas their socialism claimed to grow out of reform liberalism, Polanyi’s search for a new Christian unity repudiated it. By the late 1930s, he was convinced of the corrosive effects of the nineteenth-century system that had severed the economy from other spheres of life and submitted human needs to the market. The consequences, as he wrote to his brother Michael, were “murderous,” for the dominance of the market prepared the world for fascism, “the most obvious failure of our civilization.” Any new humanist philosophy had to start with “freedom from economics.”

Hunger Games

The Great Transformation was originally called Origins of the Cataclysm, which then became Anatomy of the 19th Century. These would have been more vivid, and more accurate, titles. But they were bleak, and did not convey his ambition to create an epic about capitalism that would convince readers that the last thing the world needed in 1944 was a restoration of old liberal ways. This had been the mistake of 1919; instead of reforming a liberal civilization, the postwar’s architects tried “recasting the regimes that had succumbed on the battlefields” and built Europe’s tomb.

Those “regimes” were the products of the first modern globalization, which Polanyi describes in the astonishing opening chapter of The Great Transformation. The rise of the world economy rested on four “institutions”: a balance of power between states; the international gold standard; the liberal state; and the self-regulating market, which produced “unheard-of material welfare.” This great transformation was responsible for “the hundred years’ peace,” but it was also a “stark utopia”—stark because of its brutal physical and moral consequences, utopian because it depended on greats acts of will and denial of the reality of social and economic life. The commodification of land, labor, and capital was the result of an organized, wrenching dislocation from collective moorings in “the traditional unity of a Christian society.” Societies with markets ceded to market societies, bent to live and die in exchange.

The final drafting of The Great Transformation did not take place in England, though. Needing an income and wanting to focus on his master work, Polanyi received help from the Rockefeller Foundation to decamp to the United States, where he was a visiting scholar at Bennington, in Vermont. Polanyi’s wife, Ilona, stayed behind in England. At Bennington Polanyi turned his WEA classes into a series of public lectures, delivered between the fall of France in the summer of 1940 and the end of the Battle of Britain in October. The Polanyis’ marital correspondences from this time are frankly discomfiting, for while Ilona writes to Karl about bombings and scarcities, he writes to her about the pleasures of pastoral New England and the open stacks of the Columbia University library.

While Ilona wrote to Karl about bombings and scarcities, he wrote to her about the pleasures of pastoral New England.

The Great Transformation’s invective follows the ways in which old feudal collectives, guilds, corporations, and craft circles—the staples of Romantic attachments to a telluric past—became treated as commodities by the market, in Polanyi’s words, “commodity fictions.” His epic centered on the way the poor, severed from the land, got stripped of their access to charity. A rising middle class won the right to vote in 1832. In Polanyi’s reading, the poor lost their “right to live” two years later with the Poor Law reform. Unable to count on subsistence from parishes under the Speenhamland system, they lined up at the gates of the workhouse. “No government was needed to maintain this balance,” Polanyi noted of the cruel twist of the self-regulating market; “it was restored by the pangs of hunger on the one hand, the scarcity of food on the other.”

There was nothing natural about this process. “Free markets,” he wrote, “could never have come into being merely by allowing things to take their course.” But—and here’s the rub—political economists campaigned to tell a very different story, and invent an increasingly elaborate set of theories, about laissez faire. It became the new creed, a creed so powerful that all subsequent anti-laissez-faire legislation got treated as an interference with or perversion of the natural course of events. In his WEA lectures from the late 1930s, he indicted the founders of the dismal science, Robert Malthus and David Ricardo: “Misery was regarded as nature’s cure, and any act of humanitarianism as a crime against humanity since it must necessarily increase their sufferings.”

What started as an uprooting from communities of reciprocity and redistribution and the victory of individual gain came full circle with welfare systems, both democratic and authoritarian, in the 1930s. The market restoration of the 1920s had failed. Gold collapsed, the old balance of imperial powers fizzled, the self-regulating market produced mass unemployment, and the liberal state got swept away. Now, Polanyi argued, the marketplace was being restored to its rightful place at the service of society. “Undoubtedly,” he noted, “our age will be credited with having seen the end of the self-regulating market.” Managed currencies, protectionism, and make-work declared the arrival of moral economy.

Bare Society

Polanyi’s zeal to incriminate liberalism blinded him. Everything that was bad about the world could be traced to one single source. Lethal, industrial-scale racism? The fault of liberals. Internationalism? A connivance of old plutocrats. The result was a tangled understanding of nationalism, which he saw as a way to restore a sense of fraternal community in the face of the globalist shredder. This was an incongruous resting point for someone without a nation, Jewish, Hungarian, or English. Of Japan’s invasion of China in 1937 or Hitler’s parade into Austria in 1938? Of the cleansing of minorities from national communities in Central Europe? Polanyi was relatively silent, though he knew full well what the Nazi sweep of Vienna implied for old friends and family.

The Great Transformation is riddled with problems. Fred Block and Margaret Somers, who have done so much to chart the outlines of a Polanyian approach to sociology, have identified one particular tension at the core of the work. On the one hand, Polanyi argues that the liberal age had disembedded the economy from wider social systems. On the other, Polanyi implies that the market always rests on legal, intellectual, and political conditions—that supply and demand never operate freely. Polanyi wants it both ways. Close readers will find themselves chasing the tail of his argument.

There are also big gaps. Above all, while the narrative dwells on the rise of the Satanic Mill to the 1830s, Polanyi never follows the story beyond. Doing so would have exposed some uncomfortable evidence about how the gold standard, free trade, and haute finance yielded a bonanza of Victorian globalization. Polanyi prefers the gory days over the glory days of the liberal order.

And these are not the only serious flaws. While Polanyi indicts the transformation for physically dehumanizing workers and leaving owners “morally degraded,”he contends that the regimes of the 1930s addressed want and anxiety by domesticating markets and restoring national sovereignty. What kind of an improvement was this? How could a shrewd observer, exiled for his convictions, and following closely the news of the horrors, see redemption without falling prey to wishful thinking? Polanyi knew full well how the furies of nationalism were killing the families and neighbors he had left behind in Hungary and Austria. He and Ilona repeatedly helped straggling kin from the late 1930s. By 1942 there was knowledge of the fate of the Jews of the East. Polanyi’s sister Sophie was caught in Vienna, faced with a dilemma posed by Nazi gendarmes: sacrifice her husband in Dachau or relinquish her mentally-ill son to the police. Given the agonizing choice, she dithered until it was too late. Her last-known location was Kielce ghetto, created by the SS in Poland as a staging ground for the extermination camps. By then she was beyond her brothers’ desperation to save her. Polanyi would later mourn that “my dearest little sister was murdered by the madmen.”

Polanyi wanted it both ways. On the one hand, he argued that the liberal age had disembedded the economy from wider social systems. On the other, he implied that supply and demand never operate freely.

One of troubles with The Great Transformation is that Polanyi wanted to sound like a realist. But he had the voice of a moralist. Consider the adjectives he uses to describe liberals and political economists. They inhabit a world of illusions. “To the stupefaction of the vast majority of contemporaries,” he notes of economic liberals, “unsuspected forces of charismatic leadership and autarchist isolationism broke forth and fused societies in new forms.” Elsewhere Polanyi points at those who extolled the virtues of the Hundred Years’ Peace—A. J. Toynbee, Ludwig von Mises, and Norman Angell—singling out their “naïveté,” a word that recycles often in the text. “Awareness of the essential nature of the problems of politics sank to an unprecedented low point” on the eve of World War I.

But it would take effort to not notice Polanyi’s own naïveté on display in the book. Liberalism, he claims, now forked into two roads: one socialist and one fascist. “The difference between these two is not primarily economic. It is moral and religious.” What those differences were was never very clear. Nor was the option posed by the society at his doorstep, the United States. Later readers tend to pay less attention to the murkier final chapters about Polanyi’s global present. Perhaps it is just as well. They are a mess.

How Obsolete Is Our Market Mentality?

Spring of 1943 brought news of the final victory of the Red Army over the German Wehrmacht at Stalingrad. “My father was impatient to return from America to England” recalled his daughter, Kari Polanyi Levitt. Polanyi rushed to complete his manuscript in Bennington so it could influence the emerging system. He sent a draft to Cole for feedback. Cole replied with extensive comments. Reflecting on the key treatment of the labor market, Cole had this to say: “I think that all through [chapter seven] you treat Speenhamland as much more universal than it was, and also make much too light of country differences in wage policy.” The book, as Cole, Tawney, and his brother Michael warned Polanyi, had many errors and exaggerations. But Polanyi was in a rush to see it go to press. When it came out, critics gave it a rough ride for its “vagueness” and “distortions.”

It was also out of step with the times. For a man who claimed realism as a badge, he was unaware of the gathering force of Keynesian macroeconomics, the colossal effort to restore market economies by American businesses, and the delegations preparing to gather in nearby Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to draft what would become the postwar financial architecture. He was, above all, oblivious of the underlying transformation in mass consumption and the importance of Fordism to re-railing capitalism. The market, for Polanyi, was a source of enrichment for plutocrats and oppression for workers, nothing more. The idea that the market could be a space for satisfying wants—and, even more, inventing them—was beyond conception. Polanyi had missed one great transformation altogether: the globalization of consumption.

If Polanyi wanted this to be his moment, and his book to provide the moral economics of a new era, he was, as Block and Somers note, a failed prophet. The idea of people submitting their individualisms to something larger—the “reality of society”—had just debased itself in horrid ways. It would take a while for the idea of group or collective rights to regain some traction.

Polanyi did not give up right away. Beyond the United States, “liberal capitalism can hardly be said to exist any more,” he would write with confidence in a 1947 essay published in Commentary. Called “Our Obsolete Market Mentality,” it outlines a “total view of man and society,” and not the splintered soul of Homo economicus. Phrases such as “the fullness of life to the person,” and the yearning for a “truly democratic society,” fill the pages, revealing a normative vision of a world emerging from catastrophe.

Polanyi’s influence on his present was almost nil. By 1947 he was ever more removed from prevailing understandings of liberal capitalism. Moral economics got paved over by a specialized, technocratic brand of economic thinking coupled to historically unprecedented growth and social safety nets. Sensing his discordance with his time, Polanyi turned away from the present, receding to focus on the economic history of ancient and tribal societies where Homo moralis played a larger role in the epic of humanity. In these areas, Polanyi’s influence was—and continues to be—profound. In his final years, he settled down outside Toronto, though even then it was not for want of a permanent home but rather because his wife Ilona, a former communist, was barred from the United States. For a moral man, Polanyi’s community ties remained strikingly thin. He shuffled to New York to give classes at Columbia, influenced the likes of Moses Finley, Marshall Sahlins, and Anne Chapman, and tapped into the largesse of the Ford Foundation to pursue his interests in ancient empires.

I first read “Our Obsolete Market Mentality” around 1980, when Polanyi was making a comeback. One of his Columbia students and close collaborators, Abraham Rotstein, gave me a photocopy of it when I was studying Canadian economic history. At the time Rotstein was embroiled in a debate over whether the colonial fur trade in North America had revealed Ojibwe people’s inner individualism as proto-NAFTA-makers. Rotstein was trying to hold the Polanyian line against a Friedmanite juggernaut. Neoclassical economics was storming to power in London and Washington, having seized it in Pinochet’s Chile. The sanctuary of economic history, even in Canada, was feeling the pressure to get with the times and to appreciate the universality of the economicus in the Homo. Margaret Thatcher, after all, gave us an epigram of the 1980s with her declaration that there was “no such thing as society,” just individuals and their families. Rotstein’s efforts went the way of so many other quests for alternatives to market fundamentalism. The case for Homo moralis got sidelined again, condemned to “critique” from the academic edges.

Maybe that is the best moral economists can hope for. But as we take stock of our long cycle of market fundamentalism and our globalization, old questions return. As it slumps, the world is scrambling to figure out what is next. Do we double down on more of the same, as post-1919 leaders did to their creaking order? There is almost no appetite for that, as Britain’s “Remainers” and Hillary Clinton’s fate showed. Having to choose between “patriots and globalists,” as Marine Le Pen and nativists worldwide argue, is no more appealing. Polanyi can help us consider the conditions that make market life work—and even endurable. But if moral economics does not want to get paved over again, it will have to find a way to get beyond the stark dichotomies that have fueled its passion, as if we must choose between ethical community or economic interdependence, morals or markets.