There is an old puzzle that goes like this: When you get to heaven, how will you know which man is Adam? The answer is that Adam will be the one man without a navel—he was never connected to an umbilical cord.

In the 1850s, evidence was mounting that life on Earth had existed longer than the six or seven thousand years that could be extracted from the Bible. Naturalist Philip Henry Gosse was a man of science as well as a committed Christian, and although he couldn’t deny this accumulation of facts, his allegiance to the Bible made it impossible for him to accept a multi-million-year evolution. His solution was to assert that God had brought the world into being entire on that first biblical morning, and with it the whole backstory of life on Earth: the Neanderthal skeletons in German caves, the sabertooths in California tar pits, all the countless remains of extinct shellfish, all the strata that only apparently took millennia to be laid down as seas rose and shrank away—and also the navel on a grown-up just-awakened Adam, and the beard on his face for that matter. God could do that, and he did. Why? Perhaps to challenge our faith: credo quia absurdum, as the early Christians could say about the weird things they were offered in sacred teachings—I believe it because it’s impossible. Gosse called the book in which he laid out this notion Omphalos, Greek for “navel.” And of course it can neither be proved nor disproved; no facts can be proffered that make it impossible, and none that can sustain it.

Many of the stories turn on a possibility in physics or mathematics or biology that either creates a world unlike ours, or shows us that our own world is not what we think it is.

Ted Chiang, best known for the story that formed the basis of the Academy Award–winning film Arrival (2018), has brought out a new volume of stories called Exhalation, and in it is a story called “Omphalos”, which takes up Gosse’s paradox and reverses it. In Chiang’s story, Adam indeed had no navel—or rather the earliest human bodies, made in the beginning by God and recently discovered mummified and complete, have no navels. Ancient trees that God brought into being full-grown have not experienced the seasons, droughts, and injuries that create the rings by which their age can be calculated. Only after their instantaneous creation did they begin to produce those rings. Other lifeforms exhibit the same effect: they came to be full-grown, and only began to change in time. The proof of God’s love for his creations, including human beings, is found in close study of such natural phenomena. So this is not our world, and a scientist who works in it addresses her questions about it to God himself in prayer; like Gosse she is a careful, thorough, dedicated researcher. Nothing she knows or learns in her work can suggest any doubts to her, and she is right not to doubt. When doubts come, they come from discoveries in astronomy, not biology: God, it seems, has other worlds he is interested in.

Chiang used to worry if he could make it as a writer because of how slowly he works—as it stands, all his published stories fit in two slim volumes, Exhalation and his first collection, Stories of Your Life and Others (2002). Yet from the first stories he published, Chiang established a style of storytelling that is his alone. Many of the stories turn on a possibility in physics or mathematics or biology that either creates a world unlike ours, or shows us that our own world is not what we think it is. In science fiction (SF)—which is what Chiang writes, though sometimes just barely—the science-fictional things are what bear the meaning and produce the emotional force of the story, and Chiang’s science-fictional things are like no other writers’, even when they turn on much-used (and abused) concepts such as quantum mechanics, time reversals, or alien contact.

In a near future, people can create ‘continuous videos of their entire lives.’ Everyone can speak fluently, but only old people write; younger people merely subvocalize to produce messages, chiefly images; they cannot spell.

Take the title story in Exhalation, which describes an enclosed universe of beings living lives entirely different from and yet precisely like our own. “It has long been said that air (which others call argon) is the source of life,” a narrator begins. “This is not in fact the case.” In (on?) this world it will turn out to be not the case, but for the beings of this world it might as well be. They are apparently metallic, and their “air” comes to them from tanks, called “lungs” herein, which are installed in their bodies and, when emptied each day, must be removed and replaced with full ones, available at public stations, where they also meet neighbors and chat. The argon (for that’s what it actually is) is piped up from a vast underground reservoir—“the great lung of the world.” When this is established for the reader, the biology gets stranger. These durable people rarely die; their titanium skins cover elaborate and delicate systems of rods and pistons by which they move and act. Brains, however, are more difficult to study, and the narrator of the story has to remove the plate at the back of his head, and with mirrors look in wonder and delight into the mechanism. At the same time (there is often an at-the-same-time in Chiang’s stories), inexplicable slowings of time are being observed; the differences of air pressure within persons and air pressure outside, which allow motion and even thought, are inching, through entropy, toward equivalence, thus death: there is no stopping it. The narrator is setting down his personal account of this for a probably imaginary future visitor, to whom he writes that “the tendency toward equilibrium is not a trait peculiar to our universe but inherent in all universes.” The same fate faces us.

A more elaborated at-the-same-time story is “The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling.” Its origin, Chiang says in his attached Story Notes, lies in the idea that writing is a technology, one that changed how human memory worked, just as new technologies of memory that are evolving now are changing it again. Two time frames take turns in the story. In one, a boy, Jijingi, who lives in a low-tech colonial territory in some prior century, becomes fascinated by a European missionary’s writing, and learns to do it himself (in a lovely moment he comes to understand that the spaces in a line of writing separate one word from another—he had never thought of words as separate, but having learned to do it in writing he can now hear it in speech.) In the other frame, set in our near future, people can create “lifelogs” with personal cams, “continuous videos of their entire lives,” useful in some ways but in practice not often consulted, and not easily searched. Then a new app, Remem, is introduced that can search your lifelog and with the slightest of hints instantaneously produce the moment you seek. In this world, everyone can speak fluently, but only old people write; younger people merely subvocalize to produce messages, chiefly images; they cannot spell. The process that Jijingi’s preliterate society undergoes is reversed in the postliterate one. Jijingi becomes a scribe and documents what elders at their tribal courts say, which doesn’t however negate the memories the elders consult to justify or judge matters. Remem and lifelogs challenge irrefutably the most solid-seeming memories of users, alternately reopening and healing old wounds. Considered together, the two story lines recall a remark in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel The Leopard (1958): “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change. D’you understand?”

Raising a digital child will involve living with the paradoxes of loving (or exploiting) a conscious being produced by engineering, but one who, like Pinocchio, can aspire to full—digital—human status.

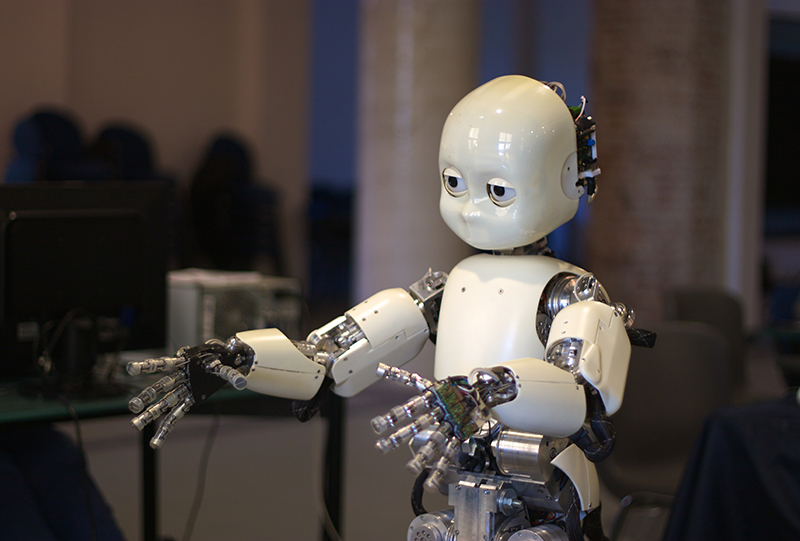

“The Life Cycle of Software Objects,” a novela included in the book, is about “digients,” AIs that, rather than being created complete and full of knowledge, begin as baby animals: an artificial tiger cub, a baby chimp, a panda. They have software genomes rather than programs, which allows for cognitive growth and unpredictable personality expression. Ana, previously a zookeeper, is hired to help with the lengthy training the digients need—as long as a human child’s. Ana comes to love Jax, a digient with the form of a child-sized robot. She has learned that her company’s digients “might be good at things that it hasn’t occurred to us to train them for,” but that’s only one surprise in this continually ramifying and thoughtful work.

Chiang’s SF differs from most SF in many ways, but the most striking—and pleasing—difference is that there are almost no villains in his stories. He shares this with Ursula K. Le Guin, who wrote: “Herds of Bad Guys are the death of a novel. . . . Whether they’re labeled politically, racially, sexually, by creed, species, or whatever, they just don’t work.” The only true villain in this collection is Morrow, deceitful dealer in “paraself” technology in “Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom,” a story which could be called noir. Mostly Chiang’s characters tend to think, intensely; they explore, go wrong, puzzle out, work through—not only science problems but personal ones, though many of the latter are the result of the former. In “The Life Cycle of Software Objects,” for example, Ana is shocked to learn that Marco, a digient attached to her friend Derek, has been sold to a company that wants to repurpose the technology to create highly responsive sex bots: “Thinking about the ways Marco might be used—without ever realizing he’s being used—makes her heart break.” Raising a digital child to autonomous individuality will involve living with the paradoxes of loving (or exploiting) a conscious being produced by engineering, but one who, like Pinocchio, can aspire to full—digital—human status. To meet such a challenge will, as Chiang has it in his notes to the story, “require the equivalent of good parenting.” Imagine that.