In early September a quiet, sixty-six-year-old man passed away in the east Texas town of Conroe. Clarence Brandley had been convicted and sentenced to die in 1981 for the rape and murder of a sixteen-year-old girl, whose nude body was found in the high school she was visiting for a volleyball game. Suspicion quickly focused on the school janitors, and Brandley was one of them. Brandley was black; the other janitors were white. “Since you’re the nigger, you’re elected,” an investigator reportedly told him. A Caucasian pubic hair was found on the victim’s body, but hair samples were taken only from Brandley. The victim was white, as was the Texas Ranger who investigated the case—along with the prosecutor who presented the evidence, the twelve jurors who heard it, and the judge who presided over the trial.

Brandley was exonerated and released in 1990, one of the earliest death row exonerations in the modern era and the first in Texas, the undisputed capital of capital punishment. In ordering a new trial, the judge who heard Brandley’s post-conviction case thought that in his thirty years on the bench he had never seen a case that “presented a more shocking scenario of the effects of racial prejudice, perjured testimony, witness intimidation” and “an investigation the outcome of which was predetermined.” In affirming the judge’s order, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found that his trial lacked even “the rudiments of fairness.” After his release, Brandley became an ordained Baptist minister and lived a life of relative anonymity until his death of pneumonia on September 2.

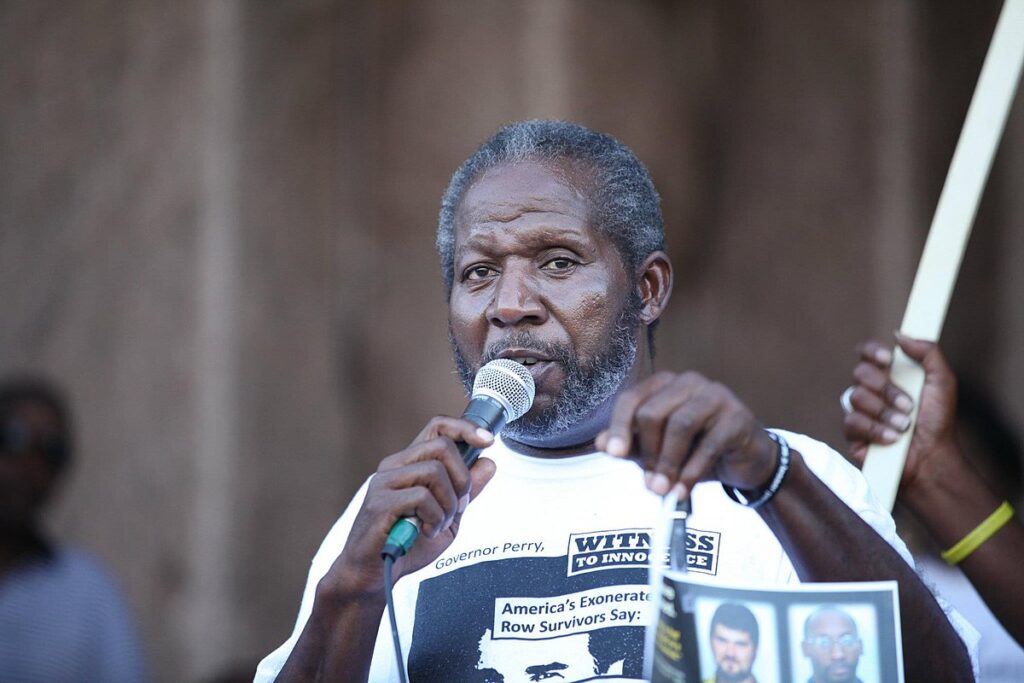

We read now and again about people like Brandley, the men and women who spend years in prison for crimes they did not commit. Reform advocates who unearth these cases hope that by assembling and publicizing enough of them, they will awaken the public to some of the flaws in the criminal justice system and trigger a call for reform. A whole campaign—called the Innocence Movement—has taken shape around this hope.

But in fact, the occasional discovery of an innocent person in prison has not had the effect these reformers would like. Releasing the Brandleys of the world—and sometimes throwing a few dollars their way, though Brandley never got so much as an apology—reassures people that even though the machinery of justice is imperfect, there is a morally just hand resting on the tiller. Ironically, righting the isolated wrongful conviction only reinforces public faith in the system as a whole; it works to prevent meaningful reconsideration of the many flaws that bedevil the criminal justice system. It is this attitude that defense lawyers and reformers struggle to upend.

The key to this process is what I call managing innocence, which takes place in two steps. First, people tend to confuse the legitimacy of the system with the accuracy of the result. Convicting “the right guy” has become the ultimate goal, and nothing else that might cast doubt on the legitimacy of the criminal justice system is considered legally or culturally relevant. And second, once we make innocence all that matters, the system erects barriers that make it all but impossible to uncover more than a very small number of innocent prisoners. The net result is a system that manages innocence, keeping it to an artfully controlled trickle.

It has not always been this way. In the middle third of the last century, largely but not entirely under the Warren Court, the United States established procedures that, in another world, might have transformed the criminal justice system. Through a series of decisions, the Supreme Court enlarged the right to counsel, barred state as well as federal prosecutors from relying on unlawfully seized evidence, invigorated the right to be free from unlawful searches, imposed limits on interrogations, narrowed the reach of the death penalty, and restrained some racist prosecutorial practices. It is an interesting thought experiment to imagine what the world would look like if we had ever taken these procedures seriously. But they were almost immediately pocked with exceptions and workarounds that reduced them to hollow rituals.

The most important escape from the imagined fetters of procedural rigor has been the attitude that the Constitution doesn’t matter if the defendant is guilty. (The same attitude underwrites many popular defenses of torture.) To be sure, the law does not speak in these terms, and no judge has ever admitted to hoarding away the benefits of the Constitution from a man merely on account of his guilt. But for decades the Supreme Court has either baked innocence into the definition of a constitutional claim or insisted on proof of innocence before concluding that a constitutional violation matters.

For instance, the Court has said that a prosecutor has a constitutional obligation to disclose exculpatory evidence, but it has also said there is no constitutional violation unless the evidence withheld is “material,” meaning it likely affected the outcome. Likewise for claims based on defense counsel’s performance: the Court has said a defendant has a constitutional right to effective assistance, but it has also said there is no violation unless counsel’s deficiencies were “prejudicial,” meaning that but for counsel’s performance, there is a reasonable probability the outcome would have been different. Likewise for the whole category of claims discounted as “harmless,” including the admission of a coerced confession. Here, the courts can agree that a constitutional violation occurred but still refuse to do anything about it because the error caused no harm, at least in the eyes of an appellate judge.

As others have observed, judges, in practice, replace these outcome-based inquiries—Was the undisclosed evidence material? Were counsel’s deficiencies prejudicial? Was the error harmful?—with another question: Is the defendant guilty? Only if the last question is answered no can the first questions be answered yes. The result is that the Constitution is largely a dead letter for a person who is, or who appears to be, guilty.

Thus were the hopeful procedures long ago neutered. Yet they produced a remarkably durable cultural trope—getting off on a technicality. People who do not know how the sausage is made seem genuinely convinced that judges routinely order the release of a defendant who committed a serious offense because some overworked police officer or underpaid prosecutor left an i un-dotted or a t un-crossed. The myth of the technicality got its first boost with Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry in 1971 and has since become a cultural mainstay. Like any civic myth, this one serves an important political function, which is to buttress the legal determination to ignore nearly everything once we are sufficiently assured of a prisoner’s guilt. And because it plays this role, it is not important that the myth bears almost no relationship to the truth. Myths that serve a political purpose are not easily felled merely because they are false.

For those who seem guilty, law and culture thus combine to exert a constant pressure to ignore the Constitution and Bill of Rights, documents ostensibly drafted to “secure the Blessings of Liberty” and provide “equal protection of the laws.” The result is a criminal justice system that tolerates an extraordinarily high level of dysfunction. We guarantee that a defendant will have a lawyer for at least part of the criminal case against her, but not that counsel will be adequately funded. We insist that people of color have a right to serve on a jury, but take no action when prosecutors contrive fanciful reasons to remove them. We proclaim that the state may not send a man to prison based on evidence unlawfully seized, but regularly allow it to do precisely that. We insist that prosecutors must disclose exculpatory evidence, but only rarely disturb a conviction when they do not. We say that money cannot buy justice, but routinely rely on fines, fees, and other monetary sanctions to make the poor pay for the system that oppresses them. And we pretend that justice is color blind, but abide racial imbalance at every step of the criminal process.

We accomplish all this by insisting that innocence alone is all that deserves our attention. It is true that cases are sometimes reversed because the police conducted an unlawful search, and convictions are sometimes overturned because the prosecutor failed to disclose exculpatory material. But these events are the exception rather than the rule.

Having channeled all criticism of the system into innocence—step one—the state then makes innocence all but impossible to unearth. To begin with, and contrary to what many people imagine, the system does not hold that the incarceration of the innocent is, in and of itself, a problem. In prevailing case law, the conclusion that a prisoner is innocent is not the same as the conclusion that the Constitution has been violated.

Suppose an officer presented false evidence and that the prevarications sent an innocent man to prison, as happened in Brandley’s case. The “violation,” according to the law, is not that an innocent man has been dispatched to a concrete and steel cell for what may be the rest of his life, but that the officer has lied. Now imagine the same man is convicted not because an officer lied but because a witness was wrong. Here there is no violation at all; there is simply a mistake—the prisoner exhibits “bare innocence,” as it is sometimes called—and the Constitution does not concern itself with mere error.

There is some uncertainty about whether this line of reasoning must be modified when it comes to the death penalty, but if we were counting judicial heads, we would have to admit that most jurists believe the Constitution is untroubled even by strapping an innocent man down to a gurney and filling his veins with poison, so long as the state did nothing wrong. That was certainly the view of Justice Antonin Scalia, for instance. To put it gently, the law has never been a friend to the innocent.

The result is perverse: innocence alone cannot help you, but its absence hurts you. To get out, the law effectively demands that prisoners demonstrate their innocence, lest a violation be dismissed as immaterial or harmless. But if that is all a prisoner can do, it will not be enough; she must also prove a procedural violation. If all a prisoner can show is her innocence, she cannot prevail. But if she cannot show her innocence, she will most assuredly fail. The result is more Escher lithograph than coherent system; it only makes sense if you do not look at it too closely.

Because innocence alone is legally irrelevant, the law does almost nothing to encourage its discovery. Once guilt has been established by proper procedures—either by a trial or a guilty plea—the game is up. After trial, for instance, we do not provide prisoners with a lawyer who can investigate and present new evidence of innocence; as a result, an innocent person in prison typically has no advocate. In addition, in most jurisdictions there is no funding available to litigate on behalf of a person in prison who is “merely” innocent. The enormous resources needed to investigate old cases, retain new experts, and test remaining evidence simply do not exist if the person can claim no other distinction than innocence.

To be sure, there are “innocence projects” in a handful of states, but they tend to rely on private donations, federal grants, and philanthropic largesse and cannot possibly examine more than a sliver of the cases that come to their attention. And there is no right to attorney’s fees for the few lawyers intrepid enough to undertake the task. The architecture of the system works to make innocence invisible, guaranteeing that nothing more than a few cases will ever come to light.

But wait, you say. What of all these cases I hear about? It seems a new exoneration is in the news all the time. The very fact that these cases are uncovered proves that the system works. I hear variations of this argument all the time, mostly from people who deploy it to resist devoting additional resources to criminal defendants.

Imagine a car speeding toward an intersection, about to kill or maim an innocent pedestrian crossing the street. Imagine hundreds of these cars—thousands, tens of thousands, all over the country—each about to ruin the life of a different pedestrian. In some tiny number of cases, a passerby appears and at the last minute rescues the pedestrian from certain death. I trust that no one would gaze upon the fortunate few and declare, “See! The system works.” Nor would they be reassured by the knowledge that most of the time, at most intersections, pedestrians cross the street without incident, and that the number of people maimed and killed every year is but a fraction of the total number of people who make the journey.

The idea that the system works thus rests upon the unexamined belief that there are only a few innocent people in prison. Under that assumption, the discovery of a scattered handful not only comes near to exhausting the total (after all, how many needles could possibly be hidden in that haystack?), but also proves that the process by which the person was found must be adequately robust. We are then free to starve those who search for these cases, perversely using their occasional success as evidence that they have all the resources they need.

Nothing better demonstrates this state of affairs than the DNA testing statutes that now exist in every state. On the surface, these statutes seem to provide a safety valve that gives wrongfully convicted prisoners a robust vehicle by which they may demonstrate innocence and secure freedom. But in fact, these statutes perfectly illustrate the state’s determination to manage innocence, rather than uncover it.

To begin with, the National Registry of Exonerations reminds us that the great majority of exonerations—about 80 percent—are not attributable to DNA testing. Despite TV appeal, the fact is that in thirty years, there have been only 459 DNA exonerations nationwide, compared to 1731 non-DNA exonerations. In these 2190 exonerations, the most common contributing factor is a false accusation, which often leaves no DNA trail. Yet in most states, the statute is limited to DNA evidence and makes no provision for prisoners to reexamine other types of evidence that might have led to a wrongful conviction. From the outset, therefore, the DNA statutes are likely to reach only a very small slice of the innocence pie.

To compound matters, once we drill down into these statutes, we find the commitment to unearthing innocence is superficial indeed. Most states, for instance, do not allow an inmate who pleaded guilty to later show his innocence. Yet all who practice in this field know with confidence that defendants sometimes choose to plead guilty, even when they are innocent, in order to avoid the risk of the substantially more severe penalty that would be imposed after trial. And since roughly 95 percent of all prosecutions end with a guilty plea, the fraction of innocent prisoners who could be rescued by DNA and who went to trial is miniscule indeed.

Moreover, DNA statutes routinely impose procedural hurdles that limit their reach. Most, for instance, demand that the prisoner make a preliminary showing of innocence, which means she must first go a long way toward proving her case before she can get hold of the evidence she needs to prove her case. Likewise, in a number of states, the defendant must mount his challenge within a specified period after her conviction (there is, in other words, a statute of limitations). In some places, the window is ridiculously brief. In Maine and Minnesota, the prisoner must bring his challenge within two years of conviction; in Alabama, the prisoner must bring his challenge within one year, and the statute allows testing only if the prisoner was sentenced to die.

Thus, after making innocence the Holy Grail in step one, the criminal justice system makes it invisible in step two.

Some scholars who write about innocence express surprise at this state of affairs, as though all right-thinking people should be as shocked as they are. They seem not to have considered the possibility that the criminal justice system operates exactly as intended by those in a position to change it, and do not recognize the political purpose of managing innocence.

The criminal justice system does not genuinely want to prevent the conviction of men and women like Clarence Brandley. It wants to manage them.