The news of a gunman opening fire at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, broke only days after another shooter murdered three and injured many more at a garlic festival in Gilroy, California. Just thirteen hours later came yet another deadly shooting, this time in downtown Dayton, Ohio. We are now used to the headlines marking time by the steady ebb and flow of bloodshed, but the pace is only quickening. It has been one year since Parkland. Three years since Orlando. Seven since Aurora and Sandy Hook. Is this, we always ask desperately, the new normal?

The frontier may have been closed, but in the anxious white psyche, the border remains open, threatening to undo the project of white dominance.

In the popular imagination, this age of mass shootings—tragic as it may be—began relatively recently. Live television coverage of the Columbine High School shooting in 1999 seared the now familiar image into the minds of millions: two white male teens, clad in trench coats to hide a vast arsenal of weaponry. The trope of the “troubled white male” became a kind of journalistic shorthand—a stock character whose motives, the media and law enforcement always carefully report, are “still under investigation.”

The “evidence” that emerges often casts the shooter sympathetically: he played violent video games, he was bullied at school, he showed signs of mental illness. This politically safe, NRA-approved messaging about lone wolfs crowds out discussion of white supremacist or misogynistic ideology, which is decried as a cynical attempt to “politicize” tragedy. Yet recent years have made the correlation unavoidable: the 2012 fatal shooting of six Sikh worshippers in Oak Creek, Wisconsin; the 2015 murder of nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina; eleven dead at the Pittsburgh Tree of Life synagogue just last year. And now, twenty-two victims, mostly Latinx, killed by a shooter taking up arms against a “Hispanic invasion” and the “rotting” of America.

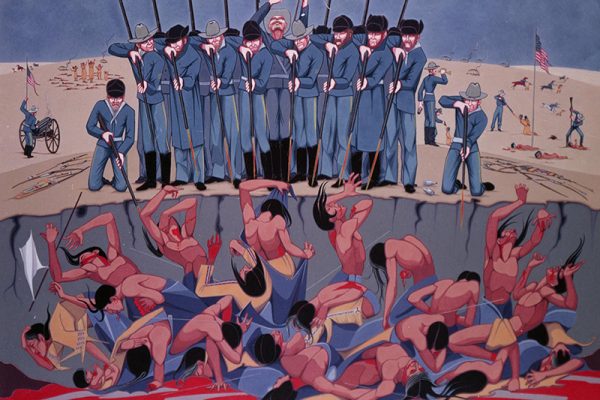

“It’s easy,” Princeton Professor of African American Studies Eddie Glaude said forcefully on MSNBC this week, “to place it all on Donald Trump’s shoulders.” But, as Glaude alludes to, the full scope of U.S. history tells a different story. Technically, the deadliest episode of domestic gun violence in the United States was committed not by a lone gunman, but by the U.S. Army. On December 29, 1890, in the midst of the so-called “Indian Wars”—the genocidal campaign to seize Native American territories by force—the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment opened fire on a largely disarmed crowd of Lakota men, women, and children at Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota. Demonstrating the lethal efficiency of the regiment’s four M1875 mountain guns—at the time heralded as a technological feat, the first breech-loading gun in military use—as many as 300 Lakota, mostly women and children, were murdered. The massacre was not an exception but the rule of colonial state-building: twenty soldiers from the 7th Cavalry Regiment went on to be awarded the awarded the Medal of Honor for their service in the bloody campaign.

The lone pioneer with a Winchester 73 has transformed into the lone gunman with an AR-15, the iconic “gun that won the West” upgraded for the assault rifle—which promises to win back the besieged nation.

There is a difference between state massacres and individual killing sprees, but pretending that Wounded Knee and El Paso are entirely unrelated only obscures the roots of today’s crisis of white supremacist violence. The truth is that contemporary gun culture is deeply intertwined with the white supremacist foundations of the United States. In her new book Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment (2018), historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz traces the history of U.S. gun culture back to the colonial government’s reliance on armed settler militias to expropriate Native lands and police slave labor. “The violent appropriation of Native land by white settlers,” she writes, “was seen as an individual right in the Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, second only to freedom of speech.” The right to bear arms enabled white settlers to defend the twin institutions of settler colonialism and chattel slavery—the theft of indigenous lands, and the use of enslaved black labor to cultivate it.

This connection to white supremacy is not just a matter of the past. “The borderlands stage the past’s eternal return,” Greg Gandin writes of the history of frontier violence still at work in Donald Trump’s policies at the border—“the place where all of history’s wars become one war.” The same could be said for the lethal nostalgia that pervades the manifestos of recent mass shooters, from the Charleston shooter, who sought a return to plantation hegemony and Jim Crow segregation, to the Pittsburgh synagogue shooter, who blamed Jews for aiding what he called an “invasion” of Latin American immigrants. The always unfinished project of white supremacy fuels the writings of these men, who, like the plantation owners and pioneers of centuries long gone, see threats to their presumed dominance on all sides. The frontier may have been closed, but in the anxious white psyche, the border remains open, threatening to undo the project of white dominance. Trump’s re-election campaign has promoted over 2,000 ads on Facebook describing immigration as an “invasion” in language that would not be out of place in the recently exposed Facebook group in which his Border Patrol agents—including the chief of the agency—joked about migrant deaths in racist, sexist memes.

The label of terrorism fails to capture that recent white supremacist violence is not ideologically opposed to the U.S. nation-state. It is less a foreign ideological strain than it is a founding DNA.

The same language of white status decline also runs through the manifesto of the El Paso gunman, who wrote that he was “honored to head the fight to reclaim my country from destruction.” Seeing a once ascendant settler colonialism turned inside out, the shooter warns that white Americans will face the same “ethnic and cultural destruction brought to the Native Americans by our European ancestors” if the supposed threat of immigration is not curbed.

That love of country—and in this case, of the shooter’s “beloved Texas”—animates such violence should come as no surprise. After all, it was “zeal for the defense of their country,” Daniel Boone wrote of the pioneers of Kentucky, that compelled those “heroes” to do battle with the “savage” Indians. The lone pioneer with a Winchester 73 has transformed into the lone gunman with an AR-15, who takes up his ancestor’s mantle in order to defend his legacy. The firearm adorns this brutal, ongoing tapestry of American racial violence as both symbol and tool of white dominance: the iconic “gun that won the West” has been upgraded for the assault rifle, which promises to win back the besieged nation.

• • •

In the wake of El Paso, liberal politicians and pundits have called for white supremacist violence to be recognized as a form of domestic terrorism. As the New York Times editorial board opined, such shootings “should be condemned by America’s leaders as terrorism” and face the investigative and preventative force of the “awesome power of the state.” The FBI is already pursuing the Gilroy shooting as an act of domestic terrorism. The shooter posted a picture on Instagram the day of the shooting encouraging followers to read a nineteenth-century proto-fascist, Aryan supremacist book.)

The El Paso gunman understands the symbolic and material power of the Second Amendment better than most: it provides the last sure line of defense of white society against its demise.

And yet, the label of terrorism fails to capture that recent white supremacist violence is not ideologically opposed to the U.S. nation-state. Despite insistent parallels drawn between recent shootings and Islamic terrorism, such violence is less a foreign ideological strain than it is a founding DNA. As Dunbar-Ortiz puts it, white nationalists are not marginal to the American project; they must be “understood as the spiritual descendants of the settlers.”

Just as frontier violence marked a decisive period of American nation-building, so white supremacist shootings attempt to return the nation to its glorified colonial past. They are not instances of destructive “terrorism,” attempting to tear down society, but rather affirmative acts of white supremacist nation-building, whose aim is to restore it—as Trump’s “MAGA” promise makes clear. After all, it is the founding fathers themselves, the El Paso shooter wrote, who “have endowed me with the rights needed to save our country from the brink destruction [sic].” The gunman understands the symbolic and material power of the Second Amendment better than most: it provides the last sure line of defense of white society against its demise.

We do ourselves no favors, then, in calling white supremacy a new or resurgent form of extremism in the United States. The history of gun violence as a tool of white settlement and domination makes this willful conflation all the clearer. The scholar and abolitionist Angela Davis reminds us that “radical simply means ‘grasping things at the root.’” If we are to truly confront the roots of white supremacist mass shootings, we will have to dig much deeper.